Key Points

Using WES, we designed an extended thrombophilia panel consisting of 55 genes of significance to thrombosis.

The extended thrombophilia panel identified multiple novel genetic variants with predicted roles in thrombosis or thrombophilia.

Abstract

Genetics play a significant role in venous thromboembolism (VTE), yet current clinical laboratory-based testing identifies a known heritable thrombophilia (factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation G20210A, or a deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin) in only a minority of VTE patients. We hypothesized that a substantial number of VTE patients could have lesser-known thrombophilia mutations. To test this hypothesis, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 64 patients with VTE, focusing our analysis on a novel 55-gene extended thrombophilia panel that we compiled. Our extended thrombophilia panel identified a probable disease-causing genetic variant or variant of unknown significance in 39 of 64 study patients (60.9%), compared with 6 of 237 control patients without VTE (2.5%) (P < .0001). Clinical laboratory-based thrombophilia testing identified a heritable thrombophilia in only 14 of 54 study patients (25.9%). The majority of WES variants were either associated with thrombosis based on prior reports in the literature or predicted to affect protein structure based on protein modeling performed as part of this study. Variants were found in major thrombophilia genes, various SERPIN genes, and highly conserved areas of other genes with established or potential roles in coagulation or fibrinolysis. Ten patients (15.6%) had >1 variant. Sanger sequencing performed in family members of 4 study patients with and without VTE showed generally concordant results with thrombotic history. WES and extended thrombophilia testing are promising tools for improving our understanding of VTE pathogenesis and identifying inherited thrombophilias.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), composed of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major public health hazard, afflicting almost a million patients in the United States each year.1 Genetic variation is a significant determinant of thrombosis risk.2-6 Five inherited thrombophilias (factor V Leiden [FVL], prothrombin gene [PT] mutation G20210A, and deficiencies of protein C [PC], protein S [PS], and antithrombin [AT]) underlie a minority of VTE cases. A large number of patients with VTE lack a known thrombophilia mutation,5,7,8 suggesting that other occult factors may play significant roles in VTE.7-9

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has yielded promising findings in several VTE studies. A landmark study reported encouraging results for a 63-gene ThromboGenomics platform in evaluating patients with coagulation or platelet disorders, and in a smaller subset of patients with thrombosis.10 Several large genome-wide association studies have also identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with VTE.11-29

We hypothesized that many VTE patients would harbor occult genetic variants. Using whole-exome sequencing (WES), we explored the role of a novel 55-gene extended thrombophilia panel in identifying thrombophilias in VTE.

Methods

Patients

WES was offered to patients aged ≥18 years with provoked or unprovoked VTE, who were seen at the Inpatient Hematology Consultation Service at Yale-New Haven Hospital or in the Outpatient Hematology Clinic at Yale Cancer Center from January 2014 through August 2016. Patients who agreed to testing and whose insurance covered clinical genetic testing were included; those with a known diagnosis of active cancer at the time of VTE presentation were excluded. Patient characteristics, thrombotic history, and family history of first-degree relatives with thrombosis were recorded. Patients with VTE not occurring as a consequence of surgery, cast immobilization, trauma, hospitalization, hormonal contraception, pregnancy, a central venous catheter, or a structural anomaly (eg, Paget-Schroetter syndrome, May-Thurner syndrome, or inferior vena cava atresia or ligation) were categorized as having unprovoked VTE. A control group of patients without VTE who underwent WES for unrelated causes was similarly analyzed.30 Where possible, family history was confirmed via personal interviews and/or examination of medical records, and clinical laboratory testing for the major thrombophilias (activated PC resistance, FVL mutation, PT mutation, PC activity, PS functional, PS total and free antigen, AT activity) was compiled. Institutional review board approval was given, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic analysis and generation of extended thrombophilia panel

Venous blood was collected in a potassium EDTA tube and genomic DNA purified for WES using the Maxwell RSC Instrument (standard instrument protocol; Promega Corp). DNA fragments containing targeted coding sequences were captured using the SeqCap EZ MedExome Target Enrichment kit (Roche/Nimblegen) and sequenced on the Illumina HiSequation 2500 platform. Mean coverage of the exome was ∼×100 with 96% of the exome covered ≥8 times. The resulting sequence was analyzed for single-nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions differing from the reference genome (human genome 19 [HG19]). Variants were filtered for relevance to human disease based on population frequency (<7% allele frequency in the ExAC database31 ) and whether they were linked to a disease in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. Results were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Variants were classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards and guidelines as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variants of uncertain significance (VUS), or benign.32 The ACMG guidelines use combinations of criteria such as nature of genetic change, frequency of genetic change compared with known disease frequency, segregation in families, previous reports establishing a variant as pathogenic or benign, functional studies in vitro, and in silico analyses. Variants meeting ACMG criteria for pathogenic or likely pathogenic were defined as “probable disease-causing variants”; these included well-established pathogenic variants, novel missense alterations occurring in the same codon as well-established pathogenic variants, or variants predicted to alter RNA splicing (Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project [BDGP] splice predictor program) in genes known to be associated with thrombosis. Rare missense alterations, in-frame insertions, deletions affecting highly conserved amino acids, intronic variants whose effect on splicing was uncertain, or nonsense or frameshift alterations in the last exons or last 50 base pairs of the penultimate exon were designated as VUS. Unless otherwise noted, all mutations identified were heterozygous.

Although the entire exome was examined, based on published literature, a panel of 55 genes was selected for more focused analysis and comprised our extended thrombophilia panel (Figure 1). Most of these genes encode coagulation factors. Several have no known role in coagulation or hemostasis but have been reported in the literature as being associated with VTE based on genome-wide association studies or SNP analyses.11,12,20,25,28,29,33,34 Many genes are associated with altered levels of PC, von Willebrand factor (VWF), and/or factor VIII, including the ABO locus.13,14,16,21,35,36

Extended thrombophilia panel. For each gene, the standard gene abbreviation is followed in parentheses by the common name.

Extended thrombophilia panel. For each gene, the standard gene abbreviation is followed in parentheses by the common name.

Sanger sequencing was performed for specific variants in families of patients with probable disease-causing genetic variants or VUS.

Protein modeling

For selected genetic variants, the theoretical effects on protein folding, secretion, or activity were analyzed using structure visualization software (eg, PyMOL or MODELER 9v7). The pertinent coordinate files used and corresponding references for each protein are described in the appropriate figure legends.

Biologic significance of variants

The biologic significance of variants was established as follows (Table 1). Known variants previously reported in the literature as being associated with VTE were designated as “thrombotic.” Variants not definitively known to be associated with VTE but predicted to be deleterious to protein function based on protein modeling or sequencing analyses were designated as “disruptive to protein structure.” Variants of high frequency in the general population, affecting nonconserved residues, predicted not to have a structurally disruptive phenotype, or demonstrated in prior studies not to be associated with VTE, were deemed “unlikely to be significant.”

Probable disease-causing variants and VUS

| Gene . | Variant . | No. of patients . | Novel or previously-reported mutation . | Probable disease-causing variant or VUS . | Biologic significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F5 (factor V) | R506Q (factor V Leiden) | 6 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| T887S | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| R679Q | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| F2 (prothrombin) | G20210A (prothrombin gene mutation) | 2 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| IVS6+5G>A | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| PROS1 (PS) | Y234C | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| P76L | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| R233K | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| Homozygous S460P (Heerlen allele) | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| R40L | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| PROC (PC) | R57W | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| A301S | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| SERPINA10 (protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor) | Q384R | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| 21_23 delCCT | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| W324X | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| SERPINC1 (AT) | S426W | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure |

| D232N | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| L131F | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| 260 c.778_779insGAA | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| c.1153+5 G>C | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| SERPIND1 (heparin cofactor II) | R468C | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| SERPINE2 (protease nexin-1) | M64T | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| SERPINF2 (α-2 antiplasmin) | P451S | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| HABP2 (factor VII–activating protease) | G534E (Marburg I) | 2 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| E393Q (Marburg II) | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| C533F | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| S6I | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain | |

| THBD (thrombomodulin) | P401L | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| HRG (histidine-rich glycoprotein) | R42Q | 3 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) | R1063H | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure |

| SH2B3 (SH2B adaptor protein 3) | V402M | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| VWF (von Willebrand factor) | P2063S | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| PLG (plasminogen) | A494V | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| R490Q | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| TF (tissue factor) | R343W | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

| FGA (fibrinogen α-chain) | E729Q | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| FGG (fibrinogen γ-chain) | S245F | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| CALR (calreticulin) | Y57C | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| ADAMTS13 (ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 13) | C668R | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

| ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) | G354R | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

| Gene . | Variant . | No. of patients . | Novel or previously-reported mutation . | Probable disease-causing variant or VUS . | Biologic significance . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F5 (factor V) | R506Q (factor V Leiden) | 6 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| T887S | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| R679Q | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| F2 (prothrombin) | G20210A (prothrombin gene mutation) | 2 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| IVS6+5G>A | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| PROS1 (PS) | Y234C | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| P76L | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| R233K | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| Homozygous S460P (Heerlen allele) | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| R40L | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Thrombotic | |

| PROC (PC) | R57W | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| A301S | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| SERPINA10 (protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor) | Q384R | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| 21_23 delCCT | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| W324X | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| SERPINC1 (AT) | S426W | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure |

| D232N | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| L131F | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic | |

| 260 c.778_779insGAA | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| c.1153+5 G>C | 1 | Novel | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| SERPIND1 (heparin cofactor II) | R468C | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| SERPINE2 (protease nexin-1) | M64T | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| SERPINF2 (α-2 antiplasmin) | P451S | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| HABP2 (factor VII–activating protease) | G534E (Marburg I) | 2 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Thrombotic |

| E393Q (Marburg II) | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| C533F | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure | |

| S6I | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain | |

| THBD (thrombomodulin) | P401L | 1 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| HRG (histidine-rich glycoprotein) | R42Q | 3 | Novel | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) | R1063H | 1 | Previously reported | Probable disease-causing variant | Disruptive to protein structure |

| SH2B3 (SH2B adaptor protein 3) | V402M | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Disruptive to protein structure |

| VWF (von Willebrand factor) | P2063S | 2 | Previously reported | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| PLG (plasminogen) | A494V | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant |

| R490Q | 1 | Novel | VUS | Unlikely to be significant | |

| TF (tissue factor) | R343W | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

| FGA (fibrinogen α-chain) | E729Q | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| FGG (fibrinogen γ-chain) | S245F | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| CALR (calreticulin) | Y57C | 1 | Previously reported | VUS | Uncertain |

| ADAMTS13 (ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 13) | C668R | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

| ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) | G354R | 1 | Novel | VUS | Uncertain |

The biologic significance of each variant was categorized as “thrombotic,” “disruptive to protein structure,” “unlikely to be significant,” or “uncertain,” based on definitions in “Methods.”

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed using the Fisher exact test. A P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

WES in study population and controls

Sixty-four patients with VTE underwent WES (Table 2). Median age of first VTE was 35.5 years (range, 14-78 years). The number of independent VTE events per patient ranged from 1 to 11. Thirty-eight patients had unprovoked VTE; 25 had VTE attributable to a provoking risk factor, a structural or anatomic cause, or both. One patient with unprovoked VTE was diagnosed 2 months later with endometrial cancer.

Patient characteristics

| Variable . | No. of patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 64 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 35 (54.7) |

| Male | 29 (45.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 45 (70.3) |

| Black | 14 (21.9) |

| Hispanic | 4 (6.3) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (1.6) |

| Thrombotic risk factors | |

| Surgery | 1 |

| Cast immobilization | 1 |

| Surgery and cast immobilization | 1 |

| Hormone exposure | 5 |

| Pregnancy | 3 |

| Surgery and hormone exposure | 2 |

| Structural/anatomic | 3 |

| Surgery and structural/anatomic | 1 |

| Central venous catheter | 3 |

| Surgery and central venous catheter | 1 |

| Hospitalization | 3 |

| Cast immobilization and trauma | 1 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Unprovoked | 38 |

| Other comorbidities | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 3 |

| Sickle cell trait | 3 |

| HIV | 1 |

| Family history of first degree relative with venous thrombosis | 41 |

| Variable . | No. of patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 64 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 35 (54.7) |

| Male | 29 (45.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 45 (70.3) |

| Black | 14 (21.9) |

| Hispanic | 4 (6.3) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (1.6) |

| Thrombotic risk factors | |

| Surgery | 1 |

| Cast immobilization | 1 |

| Surgery and cast immobilization | 1 |

| Hormone exposure | 5 |

| Pregnancy | 3 |

| Surgery and hormone exposure | 2 |

| Structural/anatomic | 3 |

| Surgery and structural/anatomic | 1 |

| Central venous catheter | 3 |

| Surgery and central venous catheter | 1 |

| Hospitalization | 3 |

| Cast immobilization and trauma | 1 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Unprovoked | 38 |

| Other comorbidities | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 3 |

| Sickle cell trait | 3 |

| HIV | 1 |

| Family history of first degree relative with venous thrombosis | 41 |

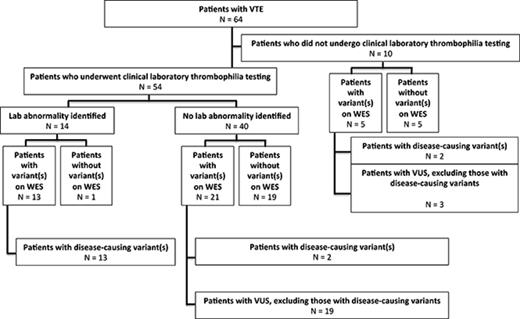

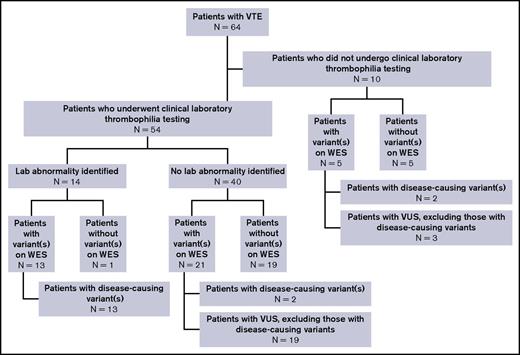

Thirty-nine patients (60.9%) were found on WES to have at least 1 genetic variant involving 1 or more of 55 genes in our extended thrombophilia panel (Figure 2). Ten patients (15.6%) had >1 pathogenic variant (Figure 3). Among the 38 patients with unprovoked VTE, 23 (60.5%) had a variant identified on WES. By comparison, of 237 control patients with no history of VTE who had undergone WES at our institution for reasons other than thrombophilia testing, only 6 had a probable disease-causing variant or VUS (2.5%): 2 had FVL (0.8%), 1 a probable disease-causing variant in SERPIND1 (c.G679A, p.R236H), and 3 VUS (SERPINA10, c.A1151G, p.Q384R; SERPINC1 c.T938C, p.M313T; SERPINC1 c.C1307T, p.A436V). The difference in the percentages of study vs control patients with probable disease-causing variants or VUS was statistically significant when considering either the entire study cohort or those with only unprovoked VTE (P < .0001).

Variants in combination. Each line represents variants identified on extended thrombophilia testing from an individual patient.

Variants in combination. Each line represents variants identified on extended thrombophilia testing from an individual patient.

Forty-one patients had a family history of a first-degree relative with venous thrombosis. The percentage of patients with VUS and a family history of thrombosis was not statistically different from patients with no family history (63.4% with positive family history vs 56.5% with no family history; P = .6).

Comparison of WES and laboratory-based thrombophilia testing

Fifty-four patients underwent clinical laboratory-based thrombophilia testing, which showed a heritable thrombophilia in 14 (25.9%; Figure 2): 6 with FVL, 3 with AT deficiency (including 1 who also had PT mutation), 2 with PT mutation (including 1 who also had AT deficiency), 2 with PS deficiency, and 1 with PC deficiency. Thirty-four (63.0%) were found on WES to have variant(s) involving at least 1 gene in the extended thrombophilia panel. The difference in the percentage of patients found by clinical laboratory testing to have a thrombophilia vs those found on WES to have a probable disease-causing variant or VUS was significant (P = .009).

In 3 of the 14 patients with abnormal clinical laboratory-based thrombophilia testing, a diagnosis of thrombophilia could not be established on the basis of such testing alone. Two had PS deficiency; in 1 case (PROS1 Y234C), the PS functional level was 57%, which was interpreted as normal due to the laboratory’s reference range being 50% to 120%, whereas in the second case (homozygous PROS1 S501P), both PS and PC activities were low (PC activity, 14%; PS activity, 25%) but attributed to concurrent warfarin use. A third patient with recurrent VTE and AT deficiency (SERPINC1 S426W) had repeatedly low AT levels measured over the span of many years, but all of these values had been drawn in the setting of acute thrombosis or while on heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin and had been deemed uninterpretable by the patient’s treating clinicians. In only 1 instance did a patient with an apparent thrombophilia on clinical laboratory testing have a negative WES study (a case of PS deficiency, with a PS functional level of 30%-40%, PS total antigen of 60%, and PS free antigen of 35%, measured several months after a diagnosis of DVT, while on rivaroxaban, with no other confounding factors).

Characterization and biologic significance of WES variants

Forty probable disease-causing variants (n = 12) or VUS (n = 28) were identified involving 22 different genes (Table 1). Of the VUS, 3 were deemed to have a thrombotic phenotype based on prior reports in the literature; 11 were predicted to be disruptive to protein structure on the basis of protein modeling or sequencing analyses, whereas 6 were deemed unlikely to be clinically significant based on a high frequency of occurrence, poor sequence conservation among homologs, or protein modeling. Biologic significance of 8 variants could not be determined due to lack of structure-function data.

Variants in common thrombophilia genes.

F5 (coagulation factor V): Three variants in F5 were identified. One was R506Q (FVL), detected in 6 patients. Another was T887S, previously described in case-control studies as being associated with venous and arterial thrombosis,17,37 as observed in the patient in our cohort. A third was a novel R679Q variant, located at a well-characterized activated PC cleavage site and predicted to disrupt protein structure, although activated PC resistance as measured in this patient was normal.

F2 (prothrombin): Two variants in F2 were identified. One was the PT mutation G20210A, found in 2 patients (including 1 with concomitant AT deficiency). The second was a novel IVS6+5G>A variant (also occurring in a patient with concomitant AT deficiency), predicted to alter the local splice donor site of F2.

PROS1 (PS): Five variants were identified in PROS1, all previously reported: Y234C, P76L, R233K, R40L, and homozygous S501P (Heerlen allele38,39 ). Y234C is known to confer 50% PS activity when present in heterozygous form,40 similar to that observed in our cohort. P76L, identified in thrombophilic families and healthy individuals, is thought to be nonpathologic, conferring little change in overall protein structure, leading to normal PS functional levels,41,42 as observed in our cohort. R233K is located in an epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain and confers a mildly deleterious phenotype of PS deficiency.43 R40L, found in 2 patients in our cohort, is a common variant described in association with thrombosis and affects the P2 position of the protein, where proteolytic cleavage occurs.42

PROC (PC): Two variants in PROC were identified, R57W and A301S (the latter in a patient who also had a novel HABP2 mutation), both previously characterized as thrombotic mutations.44,45

Variants in SERPIN genes.

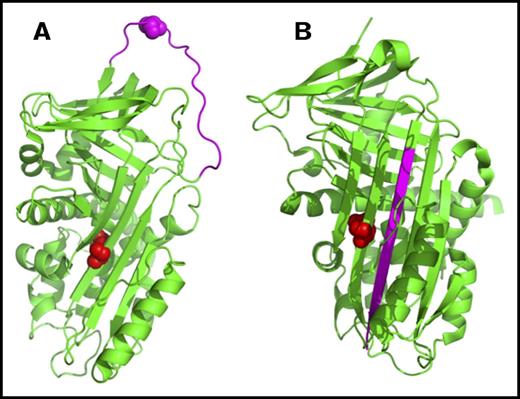

The SERPIN genes have a shared structure with a central β-sheet and a separate reactive center loop (RCL). Upon binding to a target protease, the RCL is cleaved and inserted into the central β-sheet, leading to irreversible protease inhibition (Figure 4).

SERPINA10 (protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor): Three variants were identified in the protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor, which inhibits coagulation factors Xa and XIa.46,47 One was Q384R (Q363R in the mature protein), reported previously; although the significance of this variant in VTE has been debated in the literature,48-55 mutation of this residue (located in the central β-sheet) interferes with the mechanics of RCL insertion, destabilizing protease-inhibitor complex formation (Figure 4). Another patient had a novel W324X variant (W303X in the mature protein), predicted to affect protein dimerization. A third patient had a novel SERPINA10 21_23delCCT variant, resulting in an in-frame deletion with loss of 1 of 3 adjacent leucine residues in the signal peptide of the protein, predicted to be nonpathologic.

SERPINC1 (AT): Five variants were identified in SERPINC1. One was the well-described L131F mutation (AT-Budapest).56,57 The other 4 were novel: S426W, D232N, 260 c.778_779insGAA, and c.1153+5 G>C. S426 (S394 in the mature protein) is located at the P1′ position of the RCL and is important for recognition by thrombin and other target proteases58 ; S394W is predicted to impair inhibition of clotting factors, similar to a previously reported S394L mutation (AT-Denver).59,60 D232 (D200 in the mature protein) is predicted to affect protein stability via disruption of a critical salt bridge in the central β-sheet. 260 c.778_779insGAA (occurring in a patient with a concomitant F2 IVS6+5G>A variant) is an in-frame GAA insertion at codon K260 (K228 in the mature protein), which alters a highly conserved K228-F229 sequence and may impair protein folding. The c.1153+5 G>C variant (occurring in a patient with concomitant PT G20210A) is predicted to significantly reduce efficiency of the intron 5 splice donor site, similar to another previously reported base substitution at this location.61

SERPIND1 (heparin cofactor II): Like AT, heparin cofactor II inhibits thrombin in the presence of heparin, although an association of heparin cofactor II deficiency and thrombosis has been debated.62 One patient had a novel SERPIND1 R468C variant (R449C in the mature protein). R449 makes a critical contact with thrombin in the crystal structure of the complex,63 which would be disrupted by the R449C mutation and predicted to be deleterious to protein function.

SERPINE2 (protease nexin-1): The protease nexin-1 protein is expressed by different tissue types in response to injury and is believed to have antithrombotic and antifibrinolytic activity.64 One patient in our cohort had SERPINE2 M64T. This residue is completely conserved among homologs, although the M46T variant is fairly common (allele frequency ∼1:89 among Europeans) and, hence, the biologic significance of M64T uncertain.

SERPINF2 (α2 antiplasmin): One patient had a previously reported SERPINF2 P451S variant. Although P451 is completely conserved among homologs, P451S is expected to be nonpathologic based on its location in an exposed loop of the protein.

Representative structure of the protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor (SERPINA10) showing the 3-dimensional orientation of residue Q384 (in red) and the reactive center loop (RCL, in pink). The protein model was created using PyMOL (PDB codes: 3H5C for native and 4AFX for RCL-inserted forms). (A) The native protein. (B) Binding of a target protease to the RCL results in cleavage and insertion of the RCL into the central β-sheet.

Representative structure of the protein Z–dependent protease inhibitor (SERPINA10) showing the 3-dimensional orientation of residue Q384 (in red) and the reactive center loop (RCL, in pink). The protein model was created using PyMOL (PDB codes: 3H5C for native and 4AFX for RCL-inserted forms). (A) The native protein. (B) Binding of a target protease to the RCL results in cleavage and insertion of the RCL into the central β-sheet.

Variants in other coagulation genes.

HABP2 (factor VII–activating protease): Four variants were identified in the HABP2 gene. G534E (Marburg I polymorphism) and E393Q (Marburg II polymorphism), both previously reported, were identified in 2 patients, with 1 patient demonstrating both variants. Marburg I and II are located in the protease domain of the HABP2 protein (Figure 5A). A number of studies have reported an association of the Marburg I polymorphism with VTE, possibly due to impaired activation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator or decreased inactivation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor.65-72 The Marburg II polymorphism has not been definitively associated with any known human disease, but protein modeling suggests a potential interaction with nearby lysine residues that could impair protein function (Figure 5C). A novel C533F variant (found in a patient with concomitant PC deficiency) is predicted to disrupt a critical C533-C505 cysteine bridge (Figure 5B). The biologic significance of a fourth variant, S6I (in a patient with Birth-Hogg-Dube syndrome and additional mutations in SERPINC1, JAK2, and TF), is uncertain as no structural information exists for this portion of the protein.

THBD (thrombomodulin): A novel variant was identified in THBD, P401L, corresponding to a highly conserved residue within the C-loop of the fourth EGF domain, involved in binding of thrombin and activation of PC and thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor.73 Although an association of THBD mutations and VTE has been debated,74,75 P401L is expected to disrupt protein structure by destabilizing a critical disulfide bond (Figure 6).76

HRG (histidine-rich glycoprotein): Three patients had a novel variant at a completely conserved amino acid in HRG, R42Q. The function of this protein is uncertain, but studies suggest roles in coagulation and fibrinolysis via interactions with fibrinogen, coagulation factor XIIa, plasminogen, and heparin and involvement in the immune system.77-83 R42Q, located in the N1 domain, is predicted to reduce protein affinity for heparin and heparan sulfate, although structural studies have not been performed to confirm this.

Structure of the HABP2 protein and locations of C533, E393, and the active site residues. The protein model of HABP2 was constructed using MODELER 9v7, with the crystal structure of the homologous hepatocyte growth factor activator (PDB code: 1YC0) as a template.109 (A) The active site of wild-type HABP2 contains a catalytic triad of 3 residues (E411, H362, and S509, shown in blue and red). (B) C533 forms a cysteine bridge with C505, adjacent to G534 (the site of the Marburg I polymorphism, G534E). These 3 residues are located on the same functionally important surface loop, near the active site residue S509 and the N terminus of the protease domain. The C533F mutation is predicted to break this cysteine bridge, destabilizing these interactions and presumably reducing protein activity. (C) E393 interacts with nearby lysine residues K416 and K418, located on the same β-strand as D411 (part of the catalytic triad). The Marburg II polymorphism (E393Q) is predicted to disrupt this interaction.

Structure of the HABP2 protein and locations of C533, E393, and the active site residues. The protein model of HABP2 was constructed using MODELER 9v7, with the crystal structure of the homologous hepatocyte growth factor activator (PDB code: 1YC0) as a template.109 (A) The active site of wild-type HABP2 contains a catalytic triad of 3 residues (E411, H362, and S509, shown in blue and red). (B) C533 forms a cysteine bridge with C505, adjacent to G534 (the site of the Marburg I polymorphism, G534E). These 3 residues are located on the same functionally important surface loop, near the active site residue S509 and the N terminus of the protease domain. The C533F mutation is predicted to break this cysteine bridge, destabilizing these interactions and presumably reducing protein activity. (C) E393 interacts with nearby lysine residues K416 and K418, located on the same β-strand as D411 (part of the catalytic triad). The Marburg II polymorphism (E393Q) is predicted to disrupt this interaction.

Characterization of the THBD P401L mutation. (A) Schematic representation of thrombomodulin epidermal growth factor-like domains 4 and 5 (EGF4, EGF5). The P401 (blue), M406 (red), and C390 and C404 (yellow) residues are highlighted. Disulfide bonds are shown by yellow lines. P401 is located in the C-loop of EGF4 at the turn of a β-hairpin motif, near a critical oxidation-sensitive M406 amino acid in the linker region between EGF4 and EGF5 essential for normal thrombomodulin function. The P401L mutation is predicted to disrupt the C-loop β-turn and destabilize a disulfide bond between C390 and C404. (B) Structure of thrombomodulin EGF-like domains 4, 5, and 6 in complex with thrombin.110 The crystal structure was downloaded from the RCSB PDB database and visualized by PyMOL (PBD ID: 1DX5). Amino acids of interest in the EGF4 C-loop are highlighted.

Characterization of the THBD P401L mutation. (A) Schematic representation of thrombomodulin epidermal growth factor-like domains 4 and 5 (EGF4, EGF5). The P401 (blue), M406 (red), and C390 and C404 (yellow) residues are highlighted. Disulfide bonds are shown by yellow lines. P401 is located in the C-loop of EGF4 at the turn of a β-hairpin motif, near a critical oxidation-sensitive M406 amino acid in the linker region between EGF4 and EGF5 essential for normal thrombomodulin function. The P401L mutation is predicted to disrupt the C-loop β-turn and destabilize a disulfide bond between C390 and C404. (B) Structure of thrombomodulin EGF-like domains 4, 5, and 6 in complex with thrombin.110 The crystal structure was downloaded from the RCSB PDB database and visualized by PyMOL (PBD ID: 1DX5). Amino acids of interest in the EGF4 C-loop are highlighted.

Variants in other genes.

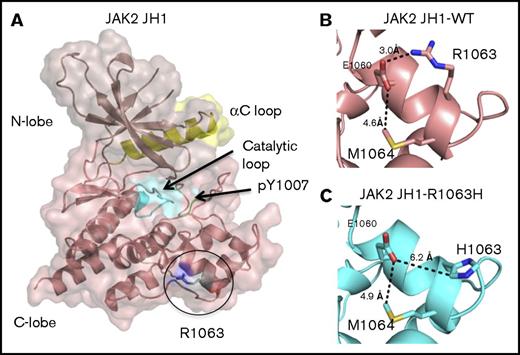

JAK2 (Janus kinase 2): One patient had an R1063H mutation in JAK2. This mutation has been previously described as a weak activator of constitutive JAK2 kinase signaling, leading to erythrocytosis when present with other JAK2 mutations,84 although the patient in our cohort did not have abnormal blood counts. The R1063H mutation would be expected to disrupt a critical salt bridge (Figure 7).

SH2B3 (SH2B adaptor protein 3): One patient had a variant in SH2B3 (LNK), V402M. This gene is involved in regulation of hematopoiesis and mediating growth factor and cytokine signaling in nonhematopoietic cells.85 Mutations in SH2B3 have been associated with various malignancies and with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome.86,87 The V402M variant affects a completely conserved amino acid in the SH2B3 protein and has been associated with myeloproliferative neoplasms,88 although a role in thrombosis has not been defined.

One patient had a variant in VWF, P2063S, previously thought to confer von Willebrand disease but now viewed as a normal variant.89,90

Two novel variants were identified in PLG (plasminogen), A494V and R490, both predicted to be insignificant based on high allele frequency or poor sequence conservation.

The biologic significance of several other variants was of uncertain significance owing to lack of supporting data: TF (tissue factor) R343W; FGA (fibrinogen α-chain) E729Q; FGG (fibrinogen γ-chain) S245F; CALR (calreticulin) Y57C; and ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) G354R.

Projected changes in JAK2 protein due to R1063H. Models were created by homology modeling on the SWISS-MODEL server and visualized using PyMOL (PDB 2B7A). (A) The JAK2-JH1 domain, with the catalytic loop highlighted in cyan, the αC loop in yellow, and phosphotyrosines within the activation loop in green. (B) In the wild-type protein, R1063 forms a salt bridge with E1060, which is exposed on the surface of the JH1 domain. (C) In the R1063H mutant protein, substitution of the charged arginine to a polar histidine results in the loss of the native salt bridge with El 060.

Projected changes in JAK2 protein due to R1063H. Models were created by homology modeling on the SWISS-MODEL server and visualized using PyMOL (PDB 2B7A). (A) The JAK2-JH1 domain, with the catalytic loop highlighted in cyan, the αC loop in yellow, and phosphotyrosines within the activation loop in green. (B) In the wild-type protein, R1063 forms a salt bridge with E1060, which is exposed on the surface of the JH1 domain. (C) In the R1063H mutant protein, substitution of the charged arginine to a polar histidine results in the loss of the native salt bridge with El 060.

Family studies

Sanger sequencing for the identified variant was completed in family members of 4 patients with positive WES testing. One patient with SERPINA10 Q384R had a fraternal twin brother with recurrent provoked and unprovoked DVT, PE, and superficial vein thrombosis, and another asymptomatic brother; Sanger sequencing in both brothers revealed the Q384R variant. A female patient with SERPINC1 260 c.778_779insGAA and F2 IVS6+5G>A had a brother with unprovoked venous thrombosis who, on Sanger sequencing, was found to have the SERPINC1 variant but not the F2 variant. One patient with both Marburg I and II had a mother with unprovoked PE who, on Sanger sequencing, was also found to have Marburg I. The other Marburg I patient had a daughter with DVT and thoracic outlet obstruction; Sanger sequencing of that daughter similarly revealed Marburg I. Additional sequencing efforts of affected and unaffected family members of other patients in our cohort are presently ongoing.

Discussion

Using WES and focusing on a novel 55-gene extended thrombophilia panel, we identified probable disease-causing mutations or VUS in 39 of 64 patients with VTE (60.9%). Forty variants were found, which were rare in a control population of patients without VTE (6 of 237, or 2.5%). Most of the variants were SNPs with mean allele frequencies of <2% and either had been previously described in association with VTE or were predicted to be disruptive to protein structure based on protein modeling.

Ten patients were found on WES to have >1 pathogenic variant. The implications of such combinations on thrombosis risk are uncertain, although genetic studies of patients with combinations of major heritable thrombophilias suggest that these risks may be additive.91 One patient in our cohort had deleterious variants in SERPINC1 260 c.778_779insGAA and F2 IVS6+5G>A and a modest thrombotic phenotype (2 VTE events, each provoked by mild risk factors), whereas her brother had the same SERPINC1 variant, without the F2 variant, and displayed a more severe phenotype (recurrent, unprovoked thrombosis leading to ischemic colitis, requiring hemicolectomy). We hypothesized that the combination of deleterious SERPINC1 and F2 variants might mitigate the severity of AT deficiency, although biochemical studies would be required to test this. Further studies are under way to explore the interactions of these and other variants.

The ability of WES and extended thrombophilia testing to diagnose thrombophilias was superior to clinical laboratory-based testing. WES correctly identified a major thrombophilia in 3 cases (2 with PS deficiency, 1 with AT deficiency) in which laboratory testing was uninterpretable due to testing conditions or concomitant anticoagulation therapy. Unlike FVL and PT mutation, diagnosis of protein deficiencies is less straightforward given variability in levels of PC, PS, and AT, limiting the ability of standard assays to detect clinically relevant deficiencies.92-95 Several groups have therefore advocated for direct genetic sequencing in evaluation of inherited protein deficiencies.96-100

In only 1 instance in our cohort did WES fail to reveal a thrombophilia that was uncovered by clinical laboratory-based thrombophilia testing (PS deficiency). This likely reflects limitations of sequencing technology; up to 50% of patients with PS or PC deficiency have negative results on NGS due to mutations in noncoding or promoter regions or involving large deletions or inversions, high copy-number variants, or other genes.96,101-103 The practice at our institution is to perform both clinical laboratory-based and extended genetic thrombophilia testing in patients in whom the decision is made to pursue a comprehensive thrombophilia evaluation.

Our extended thrombophilia panel shares some similarities with the recently reported ThromboGenomics platform, although the genes of interest between the 2 panels differ given our exclusive focus on thrombotic conditions as opposed to bleeding or platelet disorders.10 The ThromboGenomics panel contains genes with well-defined, pathogenic roles mostly in coagulation and platelet function, in addition to several thrombosis-specific genes. Our extended thrombophilia panel contains all of the same coagulation and thrombosis genes, plus several additional genes identified in NGS studies as being associated with VTE albeit with no definite roles in thrombosis. The ThromboGenomics panel also contains multiple genes responsible for inherited platelet defects, most of which were not included in our extended thrombophilia panel as these genes have not been previously linked to VTE (an exception being GP6,104 which we included). Further analysis of platelet and other coagulation genes is presently ongoing in an effort to identify novel genes.

Limitations of our study include small sample size, incomplete clinical laboratory-based thrombophilia testing, absence of biochemical data to confirm structure-function predictions, and limited family genetic studies. Some variants in our extended thrombophilia panel, particularly Marburg I and II, are known polymorphisms, which might be expected to appear incidentally in our cohort based on their reported frequencies in the general population,69 although analysis of our control population did not identify the Marburg variants. Our patient numbers did not allow for calculation of hazard ratios of VTE risk as most variants were observed only once. Additionally, the current scope of our study precluded identification of recessive mutations. Presently, we are collaborating with other groups to expand our study population, which may allow for epidemiologic analysis, and for identification of recessive variants via more comprehensive testing of affected and unaffected family members.

The clinical implications of thrombophilia testing have been debated, and thrombophilia testing is generally not recommended in patients with provoked VTE as the results do not change management.105,106 However, emerging data suggest a potential role for extended thrombophilia testing in select VTE cases, as certain thrombophilic mutations may impact thrombotic phenotype and clinical outcomes.100,107-109 Several studies have incorporated novel SNPs into risk scores for VTE prediction, with promising results.110-113 Such advancements bring personalized medicine closer to the field of thrombosis and may ultimately allow for individually tailored decisions regarding anticoagulation for both primary and secondary prophylaxis.114,115 Our findings support a need for further studies of NGS in identifying new thrombophilia mutations to expand our understanding of thrombogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to William P. Sheffield, Steven D. Gore, and Thomas P. Duffy for their insightful contributions to this manuscript.

C.R.P. was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. A.R.R. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01 HL062565.

Authorship

Contribution: E.-J.L., A.D.L, and A.I.L. wrote the manuscript; A.E.B., D.J.D., E.-J.L., and A.I.L. compiled the genes in the extended thrombophilia panel; D.J.D., A.E.B., and E.-J.L. interpreted WES results; R.M.C., E.E., P.G.d.F., K.G., S.X.G., J.A.H., S.R.L., K.M., C.R.P., A.R.R., and P.P.S. performed protein modeling and wrote portions of the manuscript pertaining to those proteins; E.-J.L., C.C., N.B., S.H., N.N., T.L.P., A.J.B., A.D., C.I.O.C., and A.I.L. contributed to the care of patients in this study; X.Y. performed statistical analyses; and J.M.C. provided major input regarding study design.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alfred Ian Lee, Section of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, Box 208028, New Haven, CT 06510; e-mail: alfred.lee@yale.edu.