Key Points

Patients treated with CAR-T therapy in Europe can achieve a quality of life comparable with that of the European general population.

A notable proportion of CAR-T recipients experience problems in physical, mental, and social well-being, requiring additional support.

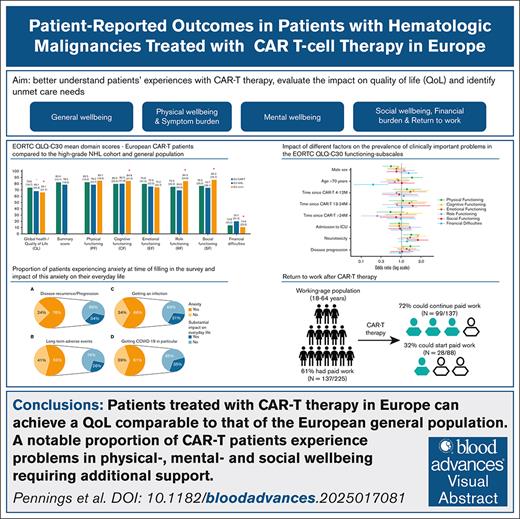

Visual Abstract

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) give direct insights into the treatment’s impact on patient’s life and complement clinical outcomes. However, since the advent of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T), PROs have been underreported. Particularly, little is known about long-term health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and dimensions such as mental- and social well-being, working life, and financial burden. Therefore, we evaluated multidimensional PROs in a cross-sectional study among European patients who received CAR-T for hematologic malignancies. Patients completed validated questionnaires (EQ-5D-5L/EORTC-QLQ-C30/PCL-5/modified-iPCQ) and ad hoc items on treatment experiences, unmet care needs, and HRQoL. The survey was available online (January–October 2023) in 7 languages. Outcomes were compared with the European general population, a matched CAR-T–naive cohort with hematologic malignancies and across subgroups, using established thresholds for clinically important differences/problems and regression models. From 10 European countries, 389 patients participated (>1 year post-CAR-T: 56%). Mean EQ-VAS was 73.1 (standard deviation, 18.5). HRQoL was similar or better than reference cohorts, except for role-, social-, and cognitive-functioning. Physical-functioning problems were most frequently reported (41%), particularly by women, older individuals, and those who experienced neurotoxicity. The latter subgroup also reported more cognitive- and social-functioning problems. Anxiety regarding disease recurrence (76%), infections (66%) and long-term side effects (59%) was common. Among working-age patients, 72% could continue paid work after CAR-T. Younger patients (32%) reported more financial difficulties than older patients (9%). This study shows favorable general HRQoL after CAR-T compared with reference cohorts. However, a notable proportion of patients experienced problems in physical-, mental- and social well-being. We identified high-risk subgroups and care needs that should be addressed during follow-up.

Introduction

Along with clinical outcomes of efficacy and toxicity, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are valuable for more comprehensive therapy evaluations. They provide direct insights into patients' experiences, which are critical for understanding the risks and benefits of a therapy from the unique patient's perspective, guiding treatment choices and patient-centered care.1,2 In the context of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, PROs, such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL), are gaining more attention and are increasingly incorporated into clinical trials. However, compared with the rapidly accumulating evidence on clinical outcomes, PRO results remain limited.

CAR-T therapy represents one of the most important advances in cancer treatment.3 High response rates and durable remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, large B-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple myeloma (MM), who previously had a poor prognosis, led to the approval of 7 CAR-T products by the US Food and Drug Administration and/or the European Medicines Agency as of 2017: tisagenlecleucel, axicabtagene ciloleucel, brexucabtagene autoleucel, lisocabtagene maraleucel, idecabtagene vicleucel, ciltacabtagene autoleucel, and obecabtagene autoleucel.4 To manufacture CAR-T products, T-cells are collected via apheresis, activated and transduced to express CARs, expanded in vitro, and reinfused into the patient.5 This manufacturing process generally takes several weeks, during which bridging therapy is often needed to stabilize or debulk the tumor. Due to rapid disease progression, infusion is unfortunately not always feasible.6

Although CAR-T therapy is among the first treatments to bring remarkable improvement to patients with R/R B-cell malignancies, for most, remissions are not permanent, leading to prognostic uncertainty.7 Also, CAR-T therapy can result in acute, potentially severe and/or long-lasting adverse events (AEs) such as cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, cytopenias, and infections. Therefore, CAR-T treatment can place a significant burden on patients’ well-being and requires stringent monitoring and long-term follow-up.8,9 Published studies report improvements in general HRQoL over time, with CAR-T therapy outperforming standard treatments such as intensive chemoimmunotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation.10-12 However, reported PROs mainly focus on general HRQoL domains, such as global health and physical functioning, whereas other critical aspects, including mental and social well-being, return to work, and financial difficulties, are less well studied. Additionally, little is known about PROs beyond 1 year after CAR-T infusion.

With the aim to better understand patients’ experiences with CAR-T therapy, evaluate the impact on HRQoL, and identify unmet needs for additional support, 2 European consortia (T2EVOLVE and QUALITOP) established a collaborative network with CAR-T–treating physicians, CAR-T and HRQoL experts, patients, patient organizations, and informal caregivers.13,14 Together, we set up a large international cross-sectional study to collect PROs from patients who received CAR-T therapy for hematologic malignancies in Europe. Here, we report on the multidimensional PROs; general, physical, mental, and social well-being, return to work, and financial burden, and compare these outcomes with those of the general population and a matched cohort of patients with hematologic malignancies treated with treatments other than CAR-T therapy.

Methods

Study design and patient population

To collect PROs a survey comprising validated questionnaires and ad hoc items on demographics, disease and treatment characteristics, treatment experience, supportive care, stress/anxiety, HRQoL, working-life, and information/educational material was developed in English. It was translated into French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch using official translations for validated questionnaires (if available) and by native speakers of the T2EVOLVE and QUALITOP consortia. Except for 1, all questions were mandatory and multiple choice. The survey was available online from January to October 2023 and disseminated by physicians, nurses, (inter)national patient organizations, and members of the T2EVOLVE Working Group of Patients and Caregivers, T2EVOLVE and QUALITOP consortia. All European adult patients (aged ≥18 years), who received CAR-T therapy for a hematologic malignancy, could participate.

Assessment of PROs in this study

HRQoL was assessed with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaires.15,16 The EORTC-QLQ-C30, a cancer-specific measure, consists of 30 questions evaluating 15 HRQoL domains: global health/QoL (QL), 5 functioning subscales (physical, cognitive, emotional, role, and social functioning), and 9 symptom subscales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties). For QL and functioning subscales, higher scores indicate better functioning, whereas higher symptom subscale scores indicate higher burden.15,17 With mean scores of 13 of 15 domains (excluding QL/financial difficulties) a QLQ-C30 summary score was calculated.18 The EQ-5D-5L consists of 5 questions evaluating health dimensions (mobility, selfcare, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) using a 5-level response scale, and the EQ-VAS rating overall health (0-100). The EQ-5D-5L index summary score (EQ-index; 0 = dead/1 = full health) was derived applying country-specific value sets (weights based on general population’s preferences representing a societal perspective on HRQoL) and can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years.16,19,20 Productivity losses were measured using a modified Institute for Medical Technology Assessment (iMTA) productivity cost questionnaire (iPCQ); excluding module 1 absenteeism, specifying questions about presenteeism and productivity losses at unpaid work, and adding items on paid work (before/after CAR-T therapy/reasons not having paid work).21 The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition) (PCL-5, past month) assesses presence/severity of PTSD symptoms in the past month with 20 items on a 5-point Likert scale (score: 0-80) to screen for a provisional PTSD diagnosis (score: ≥33).22 Impact of CAR-T treatment phases on daily life (retrospectively for past treatment phases and at time of filling in the survey for the current treatment phase) and anxiety (at time of filling in the survey) was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (“not at all,” “a little,” “quite a bit,” and “very much”). In case of substantial impact (“quite a bit” or “very much”) or any anxiety, follow-up questions appeared to specify reasons/impact. Received and appreciated (in retrospect) supportive care was evaluated at 3 phases (screening-bridging, infusion, and follow-up).

Reference populations

To interpret the EORTC-QLQ-C30 results, we used 2 reference cohorts: a European general population cohort (publicly available norm data: N = 11 343 from 11 European countries) and an age- and sex-matched cohort of patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) who were treated with treatments other than CAR-T therapy (chemo- and/or immunotherapy), using frequency-based matching (NHL cohort: characteristics provided in supplemental Table 1).23,24

Statistical analysis

All European respondents were included for analyses. Frequencies, proportions, means, medians, standard deviations (SD), and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated as appropriate. EORTC-QLQ-C30 scores were linearly transformed to calculate mean domain and summary scores (range, 0-100).17,18 Clinically relevant EORTC-QLQ-C30 mean score differences between cohorts were assessed using evidence-based domain-specific values for small differences.25 Clinically important problems (ciproblems) in EORTC-QLQ-C30 domains were identified within the CAR-T cohort using established thresholds for clinical importance (TCI; no TCI available for QL and summary score).26ciProblems were further analyzed across subgroups defined by factors putatively influencing HRQoL: sex, age (>70 vs ≤70 years), time since CAR-T infusion (≤3, 4-12, 13-24, or >24 months), neurotoxicity (yes/no), intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and progression after CAR-T therapy. Multivariable regression models including abovementioned factors were used to determine factors independently influencing EORTC-QLQ-C30 domains. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The mean EQ-VAS and EQ-index were evaluated following the EQ-5D-5L user guide for the entire CAR-T cohort and subgroups commonly used in economic evaluations (progression/progression-free, and ≤2 or >2 years post-infusion). EQ-index values were calculated for each respondent using corresponding country-specific value sets or a proxy.19,20,27 Established thresholds for minimally important differences in EQ-VAS (±7) and EQ-index (±0.08) values were used.28 Productivity losses were calculated following the iPCQ manual.29 Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2).

The survey was anonymized and all respondents provided informed consent online to participate in the study. All data, including medical information, were self-reported by patients. The study was assessed by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (W22_154#22.201).

Results

Patient, treatment, and disease characteristics

In total, 389 patients from 10 European countries participated. Patient, treatment, and disease characteristics are presented in Table 1. Median age was 61 years (range, 18-85), 37% were female, most patients had lymphoma (86%), 56% received CAR-T therapy >1 year ago, and 20% had disease progression after CAR-T therapy. Median hospital admission after CAR-T infusion was 16 days (range, 0-210), with 24% requiring ICU admission.

General well-being

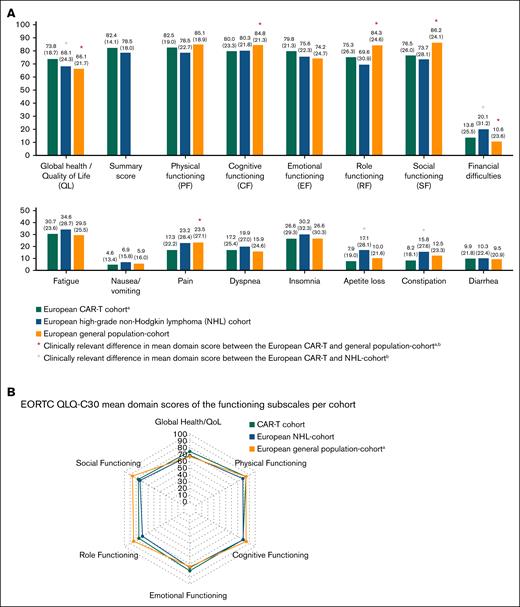

Figure 1 shows mean EORTC-QLQ-C30 domain scores in the CAR-T and reference cohorts. QL was clinically meaningfully better in the CAR-T cohort (73.8 [SD, 18.7]) compared with the general population-(66.1 [SD, 21.7]) and NHL cohort (68.1 [SD, 24.3]). Patients >2 years after infusion (79.0 [SD, 16.0]) and those without disease progression (75.1 [SD, 17.9]) had statistically significant and clinically relevant better QL than patients ≤3 months after infusion (70.3 [SD, 17.8]) and those with progression (70.6 [SD, 20.0]; supplemental Table 2). EORTC-QLQ-C30 mean domain scores and ciproblems stratified per disease type are provided in supplemental Table 3 and a direct comparison between the CAR-T lymphoma subcohort and the NHL cohort, which overall resulted in comparable outcomes for patient treated with CAR-T therapy, is provided in supplemental Figure 1.

EORTC QLQ-C30 mean domain scores (standard deviation) of the European CAR-T patients compared with a matched cohort of European patients with high-grade NHL and the European general population.23,24 EORTC QLQ-C30 mean domain scores are presented as a bar chart for all subscales (A) and for the functioning subscales also as a spider plot (B) EORTC QLQ-C30 domain scores were measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0 questionnaire. Domain scores range from 0 to 100. For QL and functioning subscales, higher scores indicate better functioning, whereas higher scores in the symptom subscales indicate higher burden. aNot matched for age, sex, or country. bA threshold for clinically relevant difference in mean domain score for emotional functioning and the summary score was not available; therefore, we used one-third of the SD of the CAR-T cohort mean domain score for emotional functioning and summary score as thresholds.

EORTC QLQ-C30 mean domain scores (standard deviation) of the European CAR-T patients compared with a matched cohort of European patients with high-grade NHL and the European general population.23,24 EORTC QLQ-C30 mean domain scores are presented as a bar chart for all subscales (A) and for the functioning subscales also as a spider plot (B) EORTC QLQ-C30 domain scores were measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0 questionnaire. Domain scores range from 0 to 100. For QL and functioning subscales, higher scores indicate better functioning, whereas higher scores in the symptom subscales indicate higher burden. aNot matched for age, sex, or country. bA threshold for clinically relevant difference in mean domain score for emotional functioning and the summary score was not available; therefore, we used one-third of the SD of the CAR-T cohort mean domain score for emotional functioning and summary score as thresholds.

In the CAR-T cohort, mean EQ-VAS was 73.1 (SD, 18.5) and mean EQ-index was 0.842 (SD, 0.177). Patients with progression after CAR-T therapy had a slightly lower EQ-VAS than those without progression (67.1 [SD, 21.2] vs 74.4 [SD, 17.9]) but almost similar EQ-indices (0.822 [SD, 0.168] vs 0.848 [SD, 0.177]). Progression-free patients >2 years post-infusion had a comparable EQ-index with those progression-free ≤2 years post-infusion (0.863 [SD, 0.142] vs 0.839 [SD, 0.193]). A comparison of EQ-indices for the 5 countries with most respondents with respective population norms is provided in supplemental Table 4.30-34

Physical well-being and symptom burden

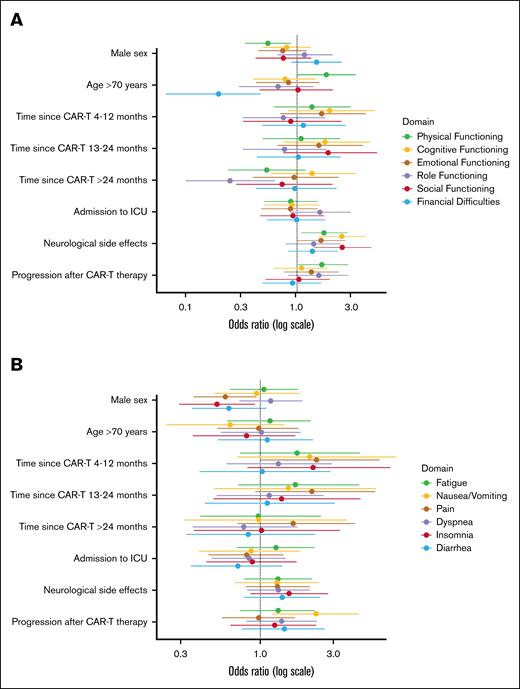

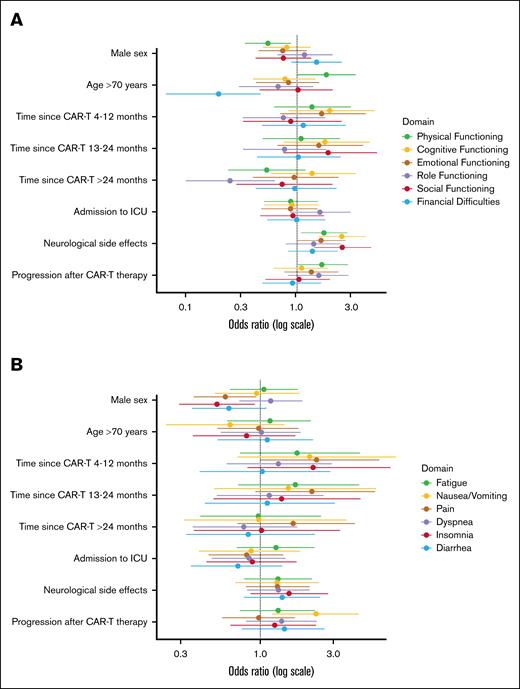

Physical-functioning was comparable between the CAR-T and reference cohorts and CAR-T recipients reported similar or clinically meaningful reduced symptom burden. Table 2 provides the prevalence of ciproblems in the EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning and symptom subscales within the total CAR-T cohort and subgroups. The impact of different factors on the prevalence of ciproblems are presented in Figure 2 and supplemental Table 5. Overall, 41% reported ciproblems in physical functioning; females (49% vs 36%), older patients (49% vs 39%), and patients who had experienced neurotoxicity (47% vs 36%) reported significantly more problems. Dyspnea (38%), pain (33%), and fatigue (28%) were most often reported as clinically important symptoms. Female patients reported significantly more pain (39% vs 30%) and insomnia (24% vs 16%), and patients with progression after CAR-T therapy reported significantly more nausea/vomiting (25% vs 13%).

Forest plots of the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals of the multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the impact of different factors on the prevalence of clinically important problems in the functioning subscales (A) and the symptom subscalesa (B).aStatistical significance testing using multivariable models was not conducted for constipation and appetite loss due to the limited number of events.

Forest plots of the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals of the multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the impact of different factors on the prevalence of clinically important problems in the functioning subscales (A) and the symptom subscalesa (B).aStatistical significance testing using multivariable models was not conducted for constipation and appetite loss due to the limited number of events.

Mental well-being

Cognitive functioning in the CAR-T cohort (mean score, 80.0 [SD, 23.3]) was similar to the NHL cohort (80.3 [SD, 21.8]), but lower than the general population cohort (84.8 [SD, 21.3]). ciProblems in cognitive functioning were reported by 34% of CAR-T recipients and significantly more often by those who had experienced neurotoxicity (45% vs 25%). Emotional functioning between the CAR-T and reference cohorts was comparable, but ciproblems were reported by 30% of CAR-T recipients, with no relevant differences across subgroups.

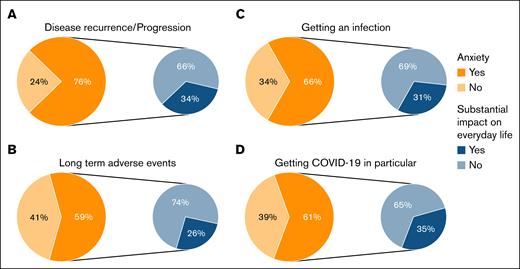

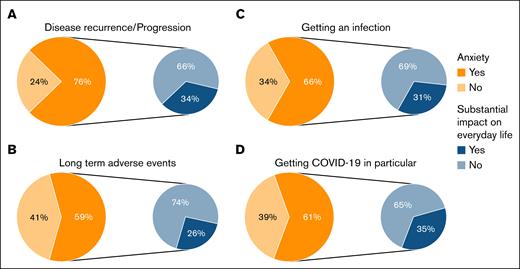

Anxiety regarding disease recurrence/progression (76%), long-term AEs (59%), infections (66%), and COVID-19 in particular (61%), were common, with approximately one-third reporting a substantial impact on everyday life (Figure 3). When comparing this anxiety between patients who received CAR-T therapy ≤1 year ago with those who received it >1 year ago, still a considerable proportion of patients experienced anxiety >1 year after CAR-T therapy (supplemental Figure 2; anxiety regarding disease recurrence/progression [71%], long-term AEs [56%], infections [69%], and COVID-19 in particular [62%]).

Proportion of patients experiencing anxiety (in orange) at time of filling in the survey regarding disease recurrence/progression (A); long-term AEs (B); getting an infection (C); and getting COVID-19 in particular (D); and impact of this anxiety on their everyday life (in blue).

Proportion of patients experiencing anxiety (in orange) at time of filling in the survey regarding disease recurrence/progression (A); long-term AEs (B); getting an infection (C); and getting COVID-19 in particular (D); and impact of this anxiety on their everyday life (in blue).

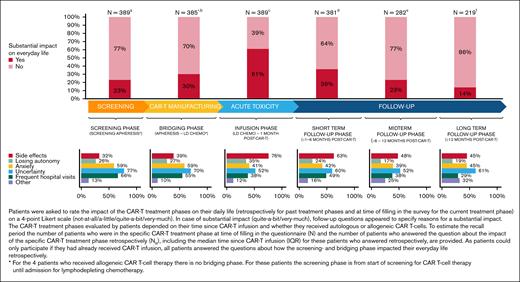

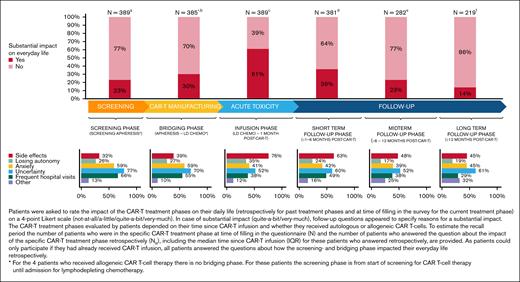

CAR-T treatment was harder than expected for 28% of patients, mostly because of AEs and prolonged hospital admission. Mainly, the infusion phase (61%) had substantial impact on patients’ everyday life, primarily because of AEs and uncertainty (Figure 4). In the long-term follow-up phase, 1 out of 7 patients indicated that CAR-T treatment still had substantial impact on everyday life, mainly because of uncertainty, anxiety, and AEs. A minority of patients (4%) met the criteria for a provisional PTSD diagnosis due to CAR-T treatment.

Impact of the different CAR-T treatment phases on everyday life and reasons for a substantial impact on everyday life.aN = 0, NR = 389; median: 13 to <19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); bN = 0, NR = 385∗; median: 13 to < 19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); cN = 8, NR = 381; median: 13 to <19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); dN = 99, NR = 282; median: 19 to 24 months (IQR, 13 to <19 months - >2 to 3 years); eN = 63, NR = 219; median: >2 to 3 years (IQR, 13 to <19 months - >2 to 3 years); fN = 219. LD CHEMO, lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Impact of the different CAR-T treatment phases on everyday life and reasons for a substantial impact on everyday life.aN = 0, NR = 389; median: 13 to <19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); bN = 0, NR = 385∗; median: 13 to < 19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); cN = 8, NR = 381; median: 13 to <19 months (IQR, 4 to <7 months - >2 to 3 years); dN = 99, NR = 282; median: 19 to 24 months (IQR, 13 to <19 months - >2 to 3 years); eN = 63, NR = 219; median: >2 to 3 years (IQR, 13 to <19 months - >2 to 3 years); fN = 219. LD CHEMO, lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

In total, 29% indicated that they would have appreciated more support during one or more phases of the CAR-T treatment trajectory (screening-bridging phase, 18%; infusion phase, 15%; and follow-up phase, 21%) and, in each phase, mental support was mentioned most often.

Social well-being, return to work, and financial burden

Mean scores of role and social functioning in the CAR-T cohort were comparable with the NHL cohort but clinically meaningfully lower than the general population cohort (Figure 1). ciProblems in role functioning were reported by 22% of patients and significantly less by those >2 years compared with ≤3 months after infusion (12% vs 30%). Also, 20% reported ciproblems in social functioning, which were more prevalent among patients who had experienced neurotoxicity (26% vs 15%). Furthermore, 28% reported that their physical condition or medical treatment caused financial difficulties. Older patients reported significantly fewer financial difficulties (9% vs 32%). For social functioning, role functioning, and financial difficulties, no associations were found for sex, progression, or ICU admission.

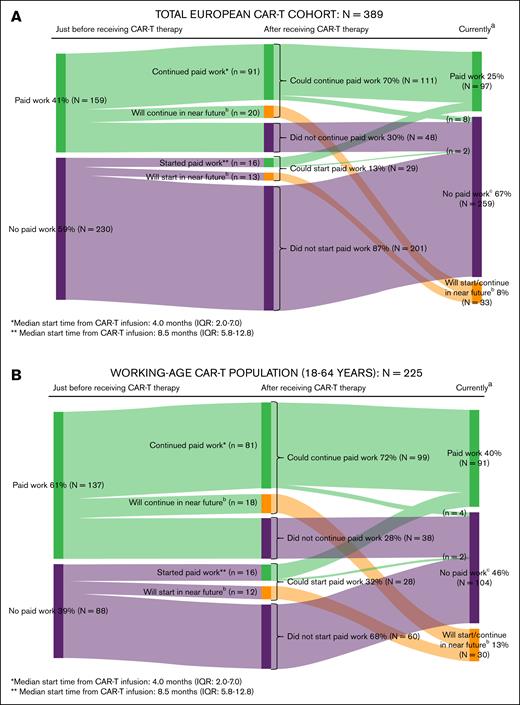

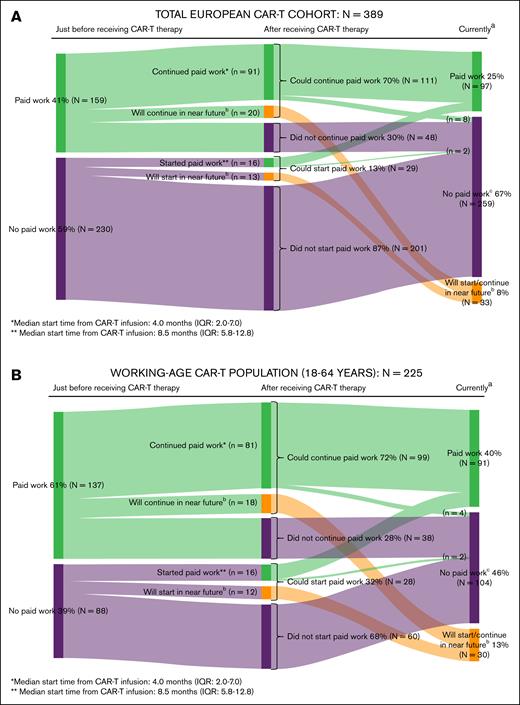

Just before CAR-T therapy, 41% (159/389) of all patients and 61% (137/225) of patients aged 18 to 64 years (working-age population) had paid work, of whom 70% (111/159) and 72% (99/137), respectively, could continue paid work after CAR-T therapy. Additionally, 13% of all patients (29/230) and 32% of the working-age population (28/88) who did not have paid work just before CAR-T therapy, could start paid work after CAR-T therapy. Among those who continued or started paid work, the median start time from CAR-T infusion was 4 (IQR, 2-7) and 8.5 months (IQR, 5.8-12.8), respectively. In the working-age population, 37% of patients who currently (at time of filling in the survey) had paid work reported suffering from physical or psychological problems relating to their cancer diagnosis or CAR-T therapy in the past month, resulting in a median productivity loss of 15.4 hours per month (IQR, 5.4-32.0; detailed information on return to work and productivity losses of [un]paid work are provided in Figure 5 and supplemental Table 6).

Return to work in the total European CAR-T cohort (A) and the working-age population (B). (A) Return to work in the total European CAR-T cohort. aAt time of filling in the survey. bA total of n = 33 respondents replied “not yet, but I will do so in the near future (ie, you will start within 3 months with paid work or you are currently applying for paid work)” to the question if they did start/continue paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy. cA total of 10 patients initially continued/started paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy but subsequently also stopped doing paid work because of (early) retirement (n = 5) or other reasons (n = 3; relapse, excessive fatigue, started studying again); reason unknown (n = 2). (B) Return to work in the working-age CAR-T population. aAt time of filling in the survey. bA total of n = 30 respondents replied “not yet, but I will do so in the near future (ie, you will start within 3 months with paid work or you are currently applying for paid work)” to the question if they did start/continue paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy. cA total of 6 patients initially continued/started paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy but subsequently also stopped doing paid work because of (early) retirement (n = 1) or other reasons (n = 3; relapse, excessive fatigue, started studying again); reason unknown (n = 2).

Return to work in the total European CAR-T cohort (A) and the working-age population (B). (A) Return to work in the total European CAR-T cohort. aAt time of filling in the survey. bA total of n = 33 respondents replied “not yet, but I will do so in the near future (ie, you will start within 3 months with paid work or you are currently applying for paid work)” to the question if they did start/continue paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy. cA total of 10 patients initially continued/started paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy but subsequently also stopped doing paid work because of (early) retirement (n = 5) or other reasons (n = 3; relapse, excessive fatigue, started studying again); reason unknown (n = 2). (B) Return to work in the working-age CAR-T population. aAt time of filling in the survey. bA total of n = 30 respondents replied “not yet, but I will do so in the near future (ie, you will start within 3 months with paid work or you are currently applying for paid work)” to the question if they did start/continue paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy. cA total of 6 patients initially continued/started paid work after receiving CAR-T therapy but subsequently also stopped doing paid work because of (early) retirement (n = 1) or other reasons (n = 3; relapse, excessive fatigue, started studying again); reason unknown (n = 2).

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the largest European study to date, evaluating PROs of CAR-T therapy in hematologic malignancies, providing a comprehensive assessment of CAR-T patients' experiences, HRQoL, and unmet needs. By actively collaborating with patients, whose experiences have been central to shaping this study, the findings provide valuable insights and highlight key aspects to address in CAR-T care plans.

General HRQoL in the CAR-T cohort was comparable with, or even better than, both reference cohorts, indicating that CAR-T patients' HRQoL compares favorably with HRQoL of patients treated with immuno/chemotherapy and that CAR-T patients can achieve a HRQoL similar to that of the general population. This is consistent with 3 randomized trials ZUMA-7, TRANSFORM, and CARTITUDE-4, that demonstrated better HRQoL along with improved overall and progression-free survival among patients with R/R large B-cell lymphoma/MM treated with CAR-T therapy (axicabtagene ciloleucel, lisocabtagene maraleucel or ciltacabtagene autoleucel, respectively) compared with standard of care.10,11,35-38

In our study, patients who received CAR-T infusion >2 years ago reported a significant clinically meaningful better overall HRQoL than patients early after infusion, suggesting ongoing HRQoL improvement over time. Similarly, longitudinal studies often show an initial decline in HRQoL, followed by improvement in HRQoL from month ±3 onward across different hematologic malignancies and CAR-T products, but data beyond 18 months are scarce.12,39,40

Despite the favorable general HRQoL observed, a substantial number of CAR-T recipients do report ciproblems across various HRQoL domains, with certain subgroups experiencing more pronounced difficulties than others. ciProblems in physical functioning were most frequently reported and more often by women, older patients, and those who had experienced neurotoxicity. Whether these differences can be objectified and could be explained by lower muscle mass in women and older patients, physical deconditioning, and/or corticosteroid-induced myopathy, should be investigated further. These subgroups may benefit from additional support, such as prehabilitation/rehabilitation.41 Notably, overall, HRQoL in older patients (aged >70 years) was comparable with that of younger patients, consistent with clinical studies showing equal efficacy and tolerability of CAR-T therapy in older patients, albeit some studies reporting higher neurotoxicity rates.42,43

Approximately one-third of patients reported clinically significant symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, and/or dyspnea. These symptoms are also commonly reported in longitudinal studies on symptom burden after CAR-T therapy and often persist even a year after infusion.44,45 Women in particular, reported more pain and sleep problems. Sex differences in ciproblems in EORTC-QLQ-C30 domains are also observed in other hematologic malignancy cohorts, indicating that women and men might have different care needs.46

Although emotional functioning was comparable between CAR-T and reference cohorts, 30% of CAR-T recipients reported ciproblems. Anxiety regarding disease recurrence, long-term AEs, and infections were common, also among patients who received CAR-T therapy >1 year ago. Fear of recurrence and struggles with making future plans due to prognostic uncertainty after CAR-T therapy has more often been reported in qualitative research.47 As CAR-T therapy is moving up to earlier lines of treatment, it would be interesting to explore in future studies whether the number of therapy lines a patient has received before CAR-T therapy influences the severity of anxiety regarding disease recurrence/progression. Although, as shown by a longitudinal study, psychological distress after CAR-T therapy tends to improve over time, at 6 months, clinically significant depression (18%), anxiety (22%), and PTSD symptoms (22%) still persist.48 In our study, a lower percentage (4%) met the criteria for a provisional PTSD diagnosis. Noteworthy, we used the most up-to-date PTSD checklist for DSM-5 instead of DSM-4. These findings underscore the need for screening and tailored mental health support. Patients in our study also expressed that, if they preferred additional support, they would have primarily appreciated mental support.

Cognitive functioning in the CAR-T cohort was similar to the NHL cohort but lower than the general population cohort. ciProblems in cognitive functioning were reported by 34% of CAR-T recipients and were significantly more prevalent in patients who had experienced neurotoxicity. These findings align with previous studies on self-perceived cognitive functioning.49,50 A longitudinal study conducting cognitive performance tests in CAR-T patients found no significant differences between baseline (day 0, 33%) and follow-up (day 360, 35%), apart from a temporary decline ±3 months after infusion that resolved spontaneously, suggesting that neurocognitive problems may not directly result from CAR-T therapy. However, future studies are needed because in this longitudinal study, only few patients experienced severe neurotoxicity.51 Nonetheless, self-reported cognitive issues after CAR-T therapy are common and the association of neurotoxicity with ciproblems in family life and social activities (social functioning) found in our study highlight the need for continued monitoring, adequate support, and further research.

Overall, CAR-T patients reported lower social and role functioning than the general population cohort. Problems reported in work, hobbies, and daily/leisure time activities (role functioning) were particularly notable early after CAR-T infusion. Encouragingly, our study shows that a considerable proportion of patients can resume or start paid work soon after CAR-T therapy. Tailored social support interventions to promote reintegration into everyday life, might improve social well-being. Importantly, 28% of CAR-T recipients reported financial difficulties. Financial toxicity, including productivity losses, travel expenses, or reduced savings has been reported previously by 20% to 50% of patients with hematologic malignancies.52 In line with other studies, younger patients reported significantly more financial difficulties than older patients, possibly due to less financial reserves and higher financial distress.52,53 The intensive CAR-T treatment trajectory and its toxicities requiring strict monitoring, frequent hospital visits/readmissions, transfusions, and IV immunoglobulin treatment may contribute to these financial problems.54 In our study, most patients were hospitalized for >2 weeks and one-fifth required temporary stays to be close enough to the hospital during the first month after infusion, with nearly half not receiving any financial compensation from an official authority to rent this temporary stay. Financial toxicity is easily overlooked but requires attention because it is associated with decreased HRQoL and survival.52,53,55

An important strength of our study is the collaborative effort of a large European network of patients, patient organizations, informal caregivers, CAR-T treating physicians, and researchers, resulting in a comprehensive assessment of PROs addressing multidimensional aspects important to patients. Consequently, almost 400 patients completed the questionnaire, which took ∼30 minutes, demonstrating their willingness to share experiences and the value they place on PROs. This is one of the very few studies evaluating long-term PROs after CAR-T therapy, including patients treated in the real-world setting, with most having received CAR-T therapy >1 year ago and as standard or care. It is, to our knowledge, the first study to describe the prevalence of ciproblems affecting daily life, alongside mean scores, per EORTC QLQ-C30 domain in CAR-T patients, using established thresholds.26 These findings can inform follow-up care plans and highlight topics that should be further explored in future studies. Also, our CAR-T cohort can serve as a reference population for interpreting individual HRQoL outcomes and as a benchmark for studies evaluating other therapies such as bispecific antibodies. Additionally, the EQ-indices can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years, providing valuable input for economic evaluations. Nonetheless, the study has several limitations. Its main focus on Western Europe limits the generalizability to other regions. The relatively small number of patients with MM and leukemia may limit extrapolation of the findings for these subgroups. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes the evaluation of HRQoL changes in individuals over time and the attribution of problems directly to CAR-T treatment. Besides, the study design is susceptible to survivorship bias and may underrepresent the experiences of patients with poorer outcomes and overestimate the outcomes of patients with progression after CAR-T therapy. Only 20% of the respondents progressed after CAR-T therapy and were probably part of the subgroup successfully treated with subsequent anticancer therapy. Because patients with progressive disease after CAR-T therapy represent a relatively small subgroup in our cohort, more research and larger cohorts are required to better understand HRQoL in these patients. To put the results into perspective, we compared our findings with reference cohorts. However, only the NHL cohort was matched for age and sex, and within the NHL cohort more patients had recently received treatment, which might have influenced the observed differences in favor of the CAR-T cohort.

In conclusion, this study revealed that, although CAR-T therapy is associated with significant toxicity, CAR-T patients overall report relatively favorable HRQoL compared with reference cohorts. Nevertheless, CAR-T treatment can profoundly affect daily life, with a notable proportion of patients experiencing problems in physical, mental, and social well-being. In addition to offering a more holistic evaluation of risks and benefits of therapies, PRO measurements can be used to recognize and monitor these clinical problems in individuals and identify subgroups at risk, enabling adequate support. Therefore, alongside clinical outcomes on efficacy and toxicity, PROs should be integrated as a core outcome in future clinical trials, real-world studies, and routine practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their caregivers, who play a very important role in supporting patients, the T2EVOLVE Working Group of Patients and Caregivers for their great efforts in codeveloping and disseminating the survey, and everyone else who helped to disseminate the survey among CAR-T recipients in Europe.

This research was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking, T2EVOLVE (under grant agreement number 945393; this Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations, and the European Hematology Association), and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program QUALITOP (under grant agreement number 875171).

This article reflects the views of the authors and not of the funders of the project.

Authorship

Contribution: E.R.A.P., A.M.S., F.W.T., C.A.U.-d.G., and M.J.K. conceptualized and designed the study; E.R.A.P., A.M.S., C.S., L.R.-O., M. Luu, M. Lorrain, M. Pina, A.K., S.S.W., and H.N. provided administrative support; E.R.A.P., A.M.S., F.W.T., S.O., A.F., C.S., M.G.D.S., Y.C., P.L., C.D., E.G.-M., O.M., U.J., J.D., M. Luu, B.H., N.B., S.C., S.N., R.D.K.L., S.A., M.R., E.C.M., A.S., M. Préau, M. Pannard, G.H.D.B., H.N., D.M.-B., M.H., C.A.U.-d.G., and M.J.K. were responsible for the provision of study materials or patients; E.R.A.P., A.M.S., and S.O. collected and assembled data; E.R.A.P., A.M.S., F.W.T., S.O., B.I.L.-W., C.A.U.-d.G., and M.J.K. analyzed and interpreted data; E.R.A.P., A.M.S., and M.J.K. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the manuscript, provided final approval of the manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects of the work. E.R.A.P. and A.M.S. contributed equally to this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.W.T. has been involved in research funded (in part) by Celgene BV, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Dutch Healthcare Institute, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, and the European Hematology Association (EHA); consulted AstraZeneca in 2020 on a reimbursement dossier for a treatment and disease indication unrelated to this project; and was invited speaker for Boehringer-Ingelheim in 2023. M.G.D.S. served on advisory boards for Roche, Janssen, and Lilly; received research grants from AstraZeneca and Gilead; and received travel support from AbbVie, Lilly, and Gilead. U.J. received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Gilead, Janssen, Miltenyi, and Novartis; and reports consultant role with Gilead and BMS. B.H. has a consulting contract with Janssen. M. Lorrain, M. Pina, and A.K. were employed by Information Technology for Translational Medicine S.A. A.S. reports honoraria from Takeda, BMS/Celgene, MSD, Janssen, Amgen, Novartis, Gilead Kite, Sanofi, Roche, Genmab, AbbVie, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Therakos, and Menarini; reports consultant role with Takeda, BMS/Celgene, Novartis, Janssen, Gilead, Sanofi, Genmab, and AbbVie; reports speakers bureau role with Takeda; reports research support from Takeda; and serves nonprofit organizations by serving in the presidency of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. S.S.W. was employed by BioSci Consulting; and reports consulting fees from King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Academic Medical Research, AMC Medical Research BV, Asthma UK, Athens Medical School, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, CHU de Toulouse, CIRO, DS Biologicals Ltd, École Polytechnique Fédérale De Lausanne, European Respiratory Society, FISEVI, Fluidic Analytics Ltd, Fraunhofer IGB, Fraunhofer ITEM, GlaxoSmithKline Research and Development Ltd, Holland & Knight, Karolinska Institutet Fakturor, KU Leuven, Longfonds, National Heart and Lung Institute, Novartis Pharma AG, Owlstone Medical Limited, PExA AB, UCB Biopharma SPRL, Umeå University, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Universita Cattolica Del Sacro Cuore, Universität Ulm, University of Bern, University of Edinburgh, University of Hull, University of Leicester, University of Loughborough, University of Luxembourg, University of Manchester, University of Nottingham, Vlaams Brabant, Dienst Europa, Imperial College London, Boehringer Ingelheim, Breathomix, Gossamer Bio, AstraZeneca, CIBER, OncoRadiomics, University of Leiden, University of Wurzburg, Chiesi Pharmaceutical, University of Liege, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, and Three Lakes Foundation (all payments to company [BioSci Consulting]). H.N. was employed by the Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier. M.H. is listed as a coinventor on patent applications and granted patents related to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technologies and CAR T-cell therapy that have been filed by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, and the University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg, Germany, that have been, in part, licensed to industry; is a cofounder and equity owner of T-CURX GmbH, Wuerzburg, Germany; and reports speaker honoraria from Novartis, Kite/Gilead, BMS/Celgene, and Janssen. C.A.U.-d.G. reports research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Cilag, Genzyme, Astellas, Sanofi, Roche, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Gilead, Merck, Novartis, Bayer, National Institutes of Health (Harvard), EHA, and ASCERTAIN (grant EU), with all payments to the institution. M.J.K. received honoraria from, and has a consulting/advisory role with, BMS/Celgene, Kite (a Gilead Company), Miltenyi Biotec, Novartis, Adicet Bio, Mustang Bio, Janssen, and Roche; reports research funding from Kite, a Gilead Company; and reports travel support from AbbVie, Roche, and BMS (all to institution). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marie José Kersten, Department of Hematology, Amsterdam UMC location VUmc, De Boelelaan 1117, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; email: m.j.kersten@amsterdamumc.nl.

References

Author notes

E.R.A.P. and A.M.S. contributed equally to this study.

Presented, in part, at the 29th Congress of the European Hematology Association, Madrid, Spain, 13 to 16 June 2024.

Presented, in part, during the “best abstract” session at the European Hematology Association–European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 7th European CAR T-cell meeting, Strasbourg, France, 6 to 8 February 2025.

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Marie José Kersten (m.j.kersten@amsterdamumc.nl).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.