Key Points

A national virtual mentorship program that pairs trainees with external mentors facilitated career development in CH.

Mentorship program participants reported an increase in academic productivity, networking, professional identity, and job opportunities.

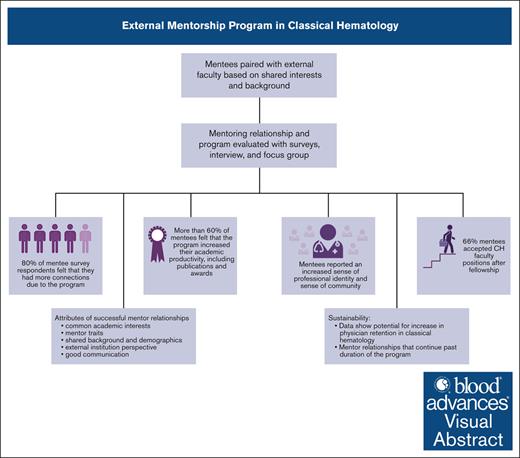

Visual Abstract

Effective mentorship is a pivotal factor in shaping the career trajectory of trainees interested in classical hematology (CH), which is of critical importance due to the anticipated decline in the CH workforce. However, there is a lack of mentorship opportunities within CH compared with medical oncology. To address this need, a year-long external mentorship program was implemented through the American Society of Hematology Medical Educators Institute. Thirty-five hematology/oncology fellows interested in CH and 34 academically productive faculty mentors from different institutions across North America were paired in a meticulous process that considered individual interests, experiences, and background. Pairs were expected to meet virtually once a month. Participation in a scholarly project was optional. A mixed-methods sequential explanatory design was used to evaluate the program using mentee and mentor surveys, a mentee interview, and a mentee focus group. Thirty-three mentee-mentor pairs (94.2%) completed the program. Sixty-three percent of mentee respondents worked on a scholarly project with their mentor; several mentees earned publications, grants, and awards. Mentee perception that their assigned mentor was a good match was associated with a perceived positive impact on confidence (P = .0423), career development (P = .0423), and professional identity (P = .0302). Furthermore, 23 mentees (66%) accepted CH faculty positions after fellowship. All mentor respondents believed that this program would increase retention in CH. This mentorship program demonstrates a productive, beneficial way of connecting mentees and mentors from different institutions to improve the careers of CH trainees, with the ultimate goal of increasing retention in CH.

Introduction

With the projected shortage of classical hematologists, the future classical hematology (CH) workforce soon may not meet the clinical demand.1,2 Assessment of factors influencing career decisions in CH revealed that mentorship is among the most influential.3 However, mentorship opportunities are perceived as less abundant within hematology compared with medical oncology.1 More mentorship opportunities within CH are needed to increase interest and retention among trainees.4

Patients with classical hematologic conditions often require lifelong, specialized care; however, a shortage of physicians specializing in this field poses a barrier to high-quality care.5,6 A survey of hematology/oncology (H/O) program directors conducted by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in 2003 and the ASH 2018 Hematology and Oncology Fellows Survey demonstrated that only ∼5% of adult H/O fellows planned to specialize in CH.4,7 Many H/O fellows perceive CH to have fewer research opportunities, less compensation, and fewer available jobs than medical oncology.1 As recently as 2021, classical hematologists voiced concerns regarding the projected CH workforce shortage, citing lack of research funding, mentorship, and accessible CH-related experiences.8 Even in the current era of virtual communication and interviews, combined H/O fellowship websites underemphasize the CH aspects of their program.9 The comparative decreased interest in CH is further affected by nomenclature such as “benign” and “nonmalignant,” which are commonly used incorrectly to describe this field.10 More H/O fellows are ultimately pursuing careers in medical oncology rather than hematology, despite viewing hematology as an intellectually stimulating field,1 leading to an inadequate number of classical hematologists.

The CH community is trying to determine what factors positively influence H/O fellows in their career decisions in hopes of identifying areas for intervention.1,3 Mentorship, which is known to influence career development and opportunities in academic medicine,11 was a critical factor in determining career decisions among H/O fellows, especially those pursuing CH.1,3,4,12 Fellow engagement in mentorship activities such as research and career planning has been shown to significantly influence hematology-only career plans.4 However, mentorship is perceived among H/O fellows to be less robust in CH compared with medical oncology, and fellows interested in CH are less likely to have mentors in this field compared with fellows interested in medical oncology or malignant hematology.1,13

Leveraging what is known about the influence of mentorship in trainees’ career decisions to enter CH, we implemented a year-long external mentorship pilot program through the ASH Medical Educators Institute (MEI) from April 2021 to April 2022. Fellows were paired with a mentor from outside of their institution based on shared interests and backgrounds. Using a mixed-methods analysis of surveys, interviews, and a focus group, we report the feasibility of the program, assessment of mentee-mentor fit, and the impact of the program on academic productivity, networking opportunities, and career development. We believe that information from this analysis demonstrates the critical role of mentorship in increasing retention in CH.

Methods

Program description

The external mentorship program was developed by 1 investigator (S.J.P.) as an ASH MEI project. The program aimed to pair H/O fellows interested in CH with mentors external to their institution for 1 year (April 2021 to April 2022). They were expected to meet virtually once a month and had the option to complete a scholarly project. This project was not considered to be research on human participants and deemed exempt by the University of California San Diego Oncology Institutional Review Board.

Program applications were open to H/O fellows from all programs and were distributed to fellowship program directors, sent to the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society (HTRS) listserv, and advertised on social media. The application was open from December 2020 to January 2021. To be eligible to participate, each applicant had to submit an application (supplemental Table 1) via Google Forms (Google, Mountain View, CA), a curriculum vitae, and a letter of support from their program director.

Mentors from institutions across the United States and Canada were recruited based on their CH expertise and academic productivity, determined based on whether they had a CH-related publication searchable on PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) within the last 2 years. Mentors and mentees were paired manually by 1 investigator (S.J.P.) with the following elements taken into consideration: CH interests (eg, neonatal hematology), areas of expertise (eg, systems-based hematology), lack of opportunities in specific areas at mentee’s institution, career plans, reasons for participating in the program, gender, race and ethnicity, personal experiences, and social media analytics. Applicants indicated their top 3 choices from a list of potential mentors. The final matching was completed by 1 investigator (S.J.P.). Mentors volunteered for this program.

Data collection

A mixed-methods sequential explanatory design was used to evaluate the program based on mentee and mentor surveys, mentee interviews, and a mentee focus group.

We created and collected program evaluation surveys using Google Forms. All surveys contained multiple choice, 5-point Likert scale, and free-text items. The mentees filled out a 12-item survey at 6 months into the program, a 34-item survey at the end of the year-long program, and a 19-item survey 6 months after the end of the program (supplemental Tables 2-4). Mentors completed a 25-item survey at the end of the program (supplemental Table 5).

All mentees were asked in the 6-month postprogram survey if they were available for an in-person interview at the 64th ASH annual meeting in New Orleans, LA, and 2 accepted. Two investigators (S.J.P. and Z.Q.) conducted the interview, and 1 investigator (Z.Q.) recorded responses using detailed, typed notes. Interviewees received monetary appreciation gift cards at the end of the session.

A virtual focus group was conducted 8 months after the program ended. All mentees were invited via email to participate; 6 mentees, distinct from the individuals interviewed at the ASH annual meeting, were available. The virtual session was held over Zoom (Zoom Video Communications; San Jose, CA) and moderated by 2 investigators (S.J.P. and Z.Q.). Participants were asked questions that were prepared by both investigators beforehand about the impact of this mentorship program. The meeting was recorded with the participants’ knowledge and verbal agreement. Afterward, all participants received a monetary gift card as a token of appreciation. The audio file was transcribed using NVivo software (Lumivero; Denver, CO). Errors in automated transcription were corrected manually by 1 investigator (Z.Q.).

Data analysis

Survey items with a 5-point Likert response such as “Participation in this external mentorship program increased my academic productivity” were grouped into 2 categories: strongly agree/agree vs neutral/disagree/strongly disagree. To compare these self-reported outcome items and participant characteristics, χ2 analysis or Fisher exact test was used. All tests were 2-sided, and a significance threshold was set for P value <.05. The analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Thematic analysis of free-text survey responses, interview notes, and focus group transcription was conducted by 2 investigators (Z.Q. and P.N.). Text from these sources were pooled and reviewed closely. Codes to describe the text based on patterns were developed and agreed upon. Each investigator assigned codes to corresponding text independently, and any discrepancies in coding were later resolved after discussion between both investigators. Codes were organized into mutually agreed upon themes.

Results

Mentee demographics

Thirty-five trainees applied; all were eligible to participate as mentees, and there were enough mentors to pair with all applicants. Therefore, all 35 mentees were accepted for this program. Eighty percent self-identified as female (Table 1). Almost half of the mentees were White, whereas the other half comprised mentees who identified as Asian, Arab, Black, Hispanic, or White and Native American. Although 86% held Doctor of Medicine degrees, 14% held Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degrees. Close to 30% were international medical graduates. About twice as many mentees had pediatric medicine training compared with adult medicine training. Most mentees were in their second and third year of fellowship during the program.

Mentee prior experience in CH

Although 70% of mentees had a mentor within CH at their home institution before applying to this program (Table 1), even those with prior mentors reported a need for more mentorship opportunities in their specific areas of interest (supplemental Table 6). Most mentees had prior CH research experiences (86%), and 26% had previously participated in academic hematology-focused programs such as the ASH Hematology Opportunities for the Next Generation of Research Scientists Award Program, HTRS Trainee Workshops, and the HTRS Hematology Fellows Consortium. The median number of prior publications was 3 (IQR 1-6), and the median number of prior poster and oral presentations at local and national conferences was 6 (IQR 3-10). However, a minority of these publications (median, 1; IQR 0-2) and presentations (median, 2; IQR 1-3) were CH related.

Feasibility of external mentorship program

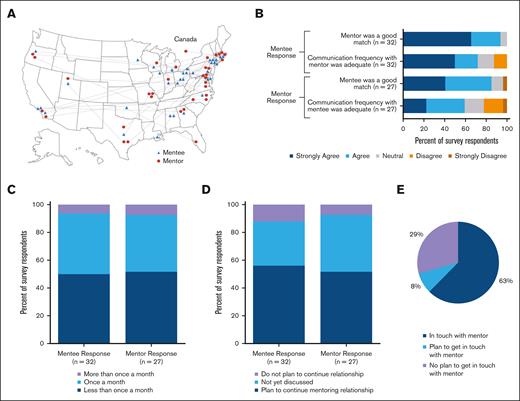

All 35 trainees who applied were paired with a mentor outside of their training institution (Figure 1A). There were 34 mentors; 1 had 2 mentees because this mentor’s field of interest aligned with both those mentees’ interests. There was greater interest among recruited faculty to participate as a mentor than there were available mentees to pair them with; 7 adult- and 17 pediatric-interested CH faculty members not paired with a mentee for the pilot program expressed willingness to participate in future cycles (supplemental Figure 1). Thirty-three of the 35 pairs (94%) completed the program; completion was defined as remaining in contact throughout the year and/or completing the 1-year program survey. One pair did not complete the program due to extenuating health circumstances, and the other pair ended their mentoring relationship amicably after recognizing they had different goals and availability with respect to their scholarly project.

Mentee-mentor pairing. (A) Thirty-five mentees were paired with 34 mentors (1 mentor with 2 mentees). Each mentee was paired with a mentor outside of their current institution. Each blue triangle represents a mentee and is placed on the map according to the location of each mentee’s training institution at the time of the program. Each red circle represents a mentor and is placed on the map according to their place of employment at the time of the program. Each dotted black line connects a blue triangle with a red circle, representing the assigned mentee-mentor pairing. (B) Likert scale type items from the mentee 1-year survey (n = 32) and mentor 1-year survey (n = 27) that specifically assessed perception of pairing and frequency of communication were plotted on a stacked bar graph. (C) Frequency of meetings as reported by both mentees and mentors in the 1-year surveys are graphed. (D) Mentee and mentor responses from the 1-year survey question that assessed whether they had discussed continuing their mentoring relationship forward after the end of the program are graphed. (E) In the postprogram survey (n = 24) distributed 6 months after the completion of program, mentees were asked whether they had been in touch with their mentor at least once since the end of the program; their responses are displayed in the pie chart. Panel A was created with BioRender.com.

Mentee-mentor pairing. (A) Thirty-five mentees were paired with 34 mentors (1 mentor with 2 mentees). Each mentee was paired with a mentor outside of their current institution. Each blue triangle represents a mentee and is placed on the map according to the location of each mentee’s training institution at the time of the program. Each red circle represents a mentor and is placed on the map according to their place of employment at the time of the program. Each dotted black line connects a blue triangle with a red circle, representing the assigned mentee-mentor pairing. (B) Likert scale type items from the mentee 1-year survey (n = 32) and mentor 1-year survey (n = 27) that specifically assessed perception of pairing and frequency of communication were plotted on a stacked bar graph. (C) Frequency of meetings as reported by both mentees and mentors in the 1-year surveys are graphed. (D) Mentee and mentor responses from the 1-year survey question that assessed whether they had discussed continuing their mentoring relationship forward after the end of the program are graphed. (E) In the postprogram survey (n = 24) distributed 6 months after the completion of program, mentees were asked whether they had been in touch with their mentor at least once since the end of the program; their responses are displayed in the pie chart. Panel A was created with BioRender.com.

Mentee-mentor relationship

Quality of pairing

Thirty-two mentees and 27 mentors responded to the 1-year survey (supplemental Table 7). Thirty mentees (94%) and 23 mentors (85%) indicated that their assigned mentor or mentee, respectively, was a good match (Figure 1B). We evaluated the percentage of mentees who thought their mentor was a good match across factors related to mentor experience. Sixteen mentors (59%) had ≥10 years of faculty experience, and 14 (52%) had previously mentored >6 mentees (supplemental Table 8). However, there was no statistically significant difference in mentee response based on mentor years of faculty experience or number of prior mentees (Table 2).

Mentee-mentor communication

Twenty-three mentees (72%) and 16 mentors (59%) thought that their frequency of communication was adequate (Figure 1B). Sixteen mentees (50%) reported meeting their mentor at least once a month (Figure 1C). Adherence to mentorship program guidelines of meeting once a month was associated with positive mentee perception of adequacy of frequency of communication. Fifteen mentees (94%) who met their mentor at least once a month thought this frequency was adequate, but only 8 mentees (50%) who met their mentor less than once a month thought this was adequate (P = .0155; Table 2).

Sustainability of mentoring relationships

Eighteen mentees (56%) and 14 mentors (52%) planned to continue their mentoring relationships beyond the 1-year duration of the program (Figure 1D). In a 6-month postprogram follow-up survey, 15 of 24 mentee survey respondents (63%) indicated that they were in touch with their mentor since completing the program, and 2 additional mentees (8%) planned to contact their mentor (Figure 1E).

Emerging themes from qualitative data regarding mentee-mentor fit

We performed a qualitative analysis on mentee and mentor survey free-text responses, mentee interviews, and a mentee focus group. Mentees described their assigned mentor to be a good match because of (1) common academic interests; (2) mentor traits such as approachability, supportiveness, and expertise; (3) shared background and demographic characteristics such as self-identified gender and/or race; (4) the fact that an external mentor provided alternative perspectives and filled a need for mentees with limited access to CH mentors at their home institution; and (5) good communication from their mentor (Table 3). Barriers identified by mentees that negatively affected mentor-mentee fit included (1) inadequate communication with mentor and (2) minimal mentor engagement (isolated to 1 mentee response). In survey responses, mentors described their pairing to be positively influenced by (1) common academic interests, (2) mentee traits such as level of effort or productivity, and (3) good communication from mentee. A few mentors noted (1) poor mentee communication, (2) low level of mentee engagement, and (3) different academic interests or goals (although mentors noted that, despite this issue, the mentoring relationship was good).

Benefits of external mentorship pilot program

Academic productivity

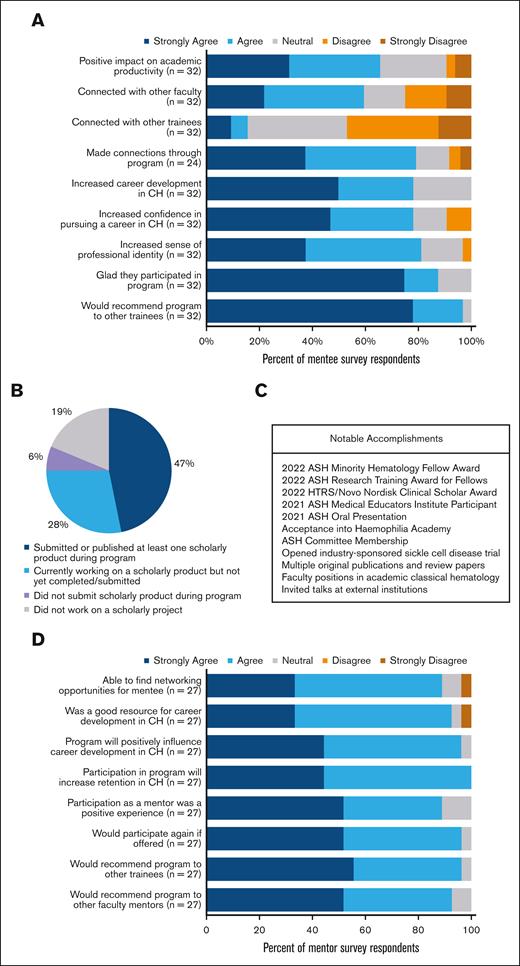

Twenty mentees (63%) participated in an optional scholarly project with their assigned mentor. Twenty-one mentees (66%) thought that participation in this program increased their academic productivity (Figure 2A). We found no statistically significant difference in perceived academic productivity based on several factors: working on a scholarly project, mentee stage of training, prior participation in formal research programs, and prior mentee CH-related publications (Table 2). Forty-seven percent of mentees who responded to the 1-year survey published or submitted for publication at least 1 scholarly product during the program, with another 28% still working on a scholarly product that was not yet completed (Figure 2B). Mentees obtained awards, grants, workshop invitations, committee memberships, conference presentations, speaking invitations, and academic faculty positions through their work with their assigned mentors (Figure 2C).

Benefits of external mentorship pilot program. A. Stacked bar graphs represent mentee response to 5-point Likert scale type items in the 1-year survey (n = 32) to questions asking about the impact of program on academic productivity, networking, career development, and professional/personal identity. One item included on this chart was asked in the 6-month postprogram survey (n = 24). (B) Pie chart shows mentee response to 1-year survey (n = 32) question asking about scholarly project and status of deliverable product. (C) List of notable academic accomplishments earned by mentees through their work with their assigned mentor in this program. (D) Stacked bar graphs represent mentor response to 5-point Likert scale type items in 1-year survey (n = 27) assessing their perception of how helpful they were in finding networking opportunities and assisting with career development of mentees, as well as their overall experience in the program.

Benefits of external mentorship pilot program. A. Stacked bar graphs represent mentee response to 5-point Likert scale type items in the 1-year survey (n = 32) to questions asking about the impact of program on academic productivity, networking, career development, and professional/personal identity. One item included on this chart was asked in the 6-month postprogram survey (n = 24). (B) Pie chart shows mentee response to 1-year survey (n = 32) question asking about scholarly project and status of deliverable product. (C) List of notable academic accomplishments earned by mentees through their work with their assigned mentor in this program. (D) Stacked bar graphs represent mentor response to 5-point Likert scale type items in 1-year survey (n = 27) assessing their perception of how helpful they were in finding networking opportunities and assisting with career development of mentees, as well as their overall experience in the program.

Networking opportunities

Nineteen mentees (59%) connected with other faculty, apart from their assigned mentor, through this program; however, only 16% of mentees connected with other trainees interested in CH (Figure 2A). There was no statistically significant difference in these responses based on whether the mentee was an adult or pediatric H/O fellow (Table 2). Six months after program completion, 19 mentees (79%) reported having more connections overall because of their participation in the program (Figure 2A). We explored mentor perception of available networking opportunities for mentees, and most mentors (89%) reported being able to find networking opportunities for their mentees if they asked for them (Figure 2D).

Career development and professional identity

Most mentees indicated that participating in this program improved their confidence in pursuing CH as a career (78%), facilitated their career development (78%), and positively affected their sense of professional identity (88%; Figure 2A). The quality of mentee-mentor match appeared to be an important factor because there was a statistically significant difference in perceived positive impact on confidence (83% vs 0%; P = .0423), career development (83% vs 0%; P = .0423), and professional identity (87% vs 0%; P = .0302) between mentees who thought their mentor was a good match vs those who did not (Table 2). Twenty-three of the 35 total mentees (66%) started CH faculty positions at academic and community medical centers after completing their fellowship; 6 mentees (17%) still in fellowship confirmed plans to pursue CH upon graduation (Table 4).

Mentors were also surveyed about their perception of this program’s impact on career development in CH. Twenty-five mentors (93%) thought they were a good resource for their mentee’s career development, and 26 (96%) thought the program positively affected mentee career development (Figure 2D). All mentor survey respondents (100%) thought this program will increase retention within CH.

Emerging themes in qualitative data regarding benefits of mentorship program

Mentees described several benefits of participating in this program in the surveys, interviews, and focus group. These include (1) academic achievements in the form of research projects, publications, presentations, and awards; (2) networking opportunities such as introduction to faculty with similar interests or attending conferences; (3) strides in career development such as confirming interest in CH and employment-related benefits such as letters of support, job opportunities, and advice; and (4) impact on personal and professional identity such as increased confidence and increased sense of community (Table 5).

Mentee and mentor satisfaction

Twenty-eight mentees (88%) were glad they participated in this program (Figure 2A). This was not associated with prior participation in formal research programs, participation in scholarly projects during the program, or mentee year in training (Table 2). However, quality of mentee-mentor relationship was statistically significantly associated with whether mentees were glad they participated in the program (93% good match vs 0% not a good match; P = .0121). Thirty-one mentees (97%) would recommend this program to other trainees (Figure 2A).

Twenty-four mentors (89%) thought participating in this program was a positive experience (Figure 2D). Twenty-six mentors (96.3%) would participate in this program again, 26 mentors (96.3%) would recommend this program to trainees, and 25 mentors (92.6%) would recommend this program to other CH faculty mentors.

Feedback for improvement

In mentee and mentor surveys, mentee interviews, and a mentee focus group, mentees and mentors provided feedback on improvements that can be made for future cycles. Areas for growth identified from analysis of qualitative data included (1) more structured guidelines to help facilitate mentoring relationships; (2) deliberate timing of program to target certain stages of fellowship; and (3) offering opportunities for in-person or group meetings to foster collaboration and networking (Table 5).

Discussion

We demonstrate the feasibility and impact of a year-long external mentorship program in CH that spanned North America. Given the shortage of classical hematologists, trainees may lack mentors at their local institutions; therefore, more mentorship in CH is needed.1 Based on the many academic accolades earned by mentees through their work with their assigned mentors and the perceived influence this program had on networking opportunities, career development, and professional identity, we show that positive and productive mentorship is possible via a virtual platform. With most mentees obtaining CH faculty positions after fellowship, we show this mentorship program has the potential to positively influence recruitment and retention in CH.

The opportunity for mentees to connect virtually with a mentor outside of their home institution was a unique and well-received aspect of our program, challenging traditional models of mentorship that emphasized that mentoring must occur in close proximity and rely on face-to-face interactions.14 Mentees ascribed having an external mentor as a strength of their mentoring relationship because they learned about different perspectives and received assistance with employment opportunities. Virtual modes of communication facilitated mentorship between individuals across different institutions and made this program feasible. Because there is increasing popularity and use of virtual communication, as well as an interest among H/O fellows in connecting with mentors virtually,13 we believe that virtual mentorship can expand the pool of mentors for trainees interested in CH. Programs such as the ASH Clinical Research Training Institute and ASH MEI are examples of hybrid programs with both in-person and virtual aspects that have successfully provided mentorship in clinical research training and medical education, respectively. Participants in our program were also interested in having in-person events, which we plan to incorporate in future cycles.

The positive feedback we received regarding the quality of assigned mentee-mentor pairing, with most pairs continuing their mentoring relationship beyond the duration of the program, demonstrates the potential benefits of assigned mentorship, which is often thought to be less favorable than self-initiated mentorship that develops over time.14-17 With the shortage of classical hematologists, it is difficult for trainees interested in CH to develop these local mentoring relationships at their institution.1,4 A formal mentorship program such as ours that holistically examines potential mentee and mentor academic and demographic background, experiences, and interests to assign mentee-mentor pairs may help fill this need by opening the door for a potentially successful mentoring relationship. Several mentees in our program also met other faculty through their mentor, indicating that assigned mentorship may provide opportunities for mentees to meet additional potential mentors.

Similar interests and similar self-reported gender and race were cited by mentees as contributing to the success of their mentoring relationship. Mentoring programs may need to include considerations regarding self-identified gender and race, given that these factors positively affected the mentee experience in our study. These data are supported by another recent study evaluating mentorship in women and trainees underrepresented in medicine pursuing surgical specialties, identifying that trainees who were women or underrepresented in medicine favored and benefited from having gender and race conformant mentors.18 For CH, this may be currently challenging, given the paucity of CH faculty at many institutions, emphasizing the need for external mentors to expand the pool of ideally matched advisers. The demographic breakdown of our applicant pool seeking mentorship opportunities reflects this need: 80% self-identified as women, who are known to be underrepresented in hematology19; and almost 30% were international medical graduates, a group that often experiences bias in hematology and academic medicine.20 Diverse representation in medicine is critical and will only grow if individuals underrepresented in medicine are supported at early stages in their career.

Mentee perception of the program’s impact on career development was associated with their perceived quality of their mentee-mentor match, suggesting that good mentorship may be an important factor in mentee career development. Formal mentorship has been identified as a key tool in increasing health care worker retention in other domains, such as, but not limited to, nursing, rural medicine, and surgery.18,21,22 With a specific focus on the impact of this program on choosing a career in CH, we were impressed that 23 mentees (66%) in our program have already obtained dedicated positions within CH. Mentors predicted that this pilot program will lead to continued careers in CH, and we predict that expansion of this program will further increase retention in CH and expand the CH workforce. Our program adds to an already growing landscape of CH-focused opportunities aimed at increasing retention. An evaluation of the HTRS Trainee Workshop, a 2-day dedicated CH experience, showed a positive influence on trainees’ decisions to pursue careers in CH.23 The ASH Hematology-Focused Fellow Training Program is a new adult hematology-only fellowship that applicants commit to through the National Resident Matching Program.24 We believe our mentorship program shares with ASH Hematology-Focused Fellow Training Program the same goal of increasing retention in CH, with the benefits of being open to both adult and pediatric H/O fellows, having career flexibility for fellows who are interested in but may not be completely decided on CH, and providing a longitudinal experience concomitant with fellowship outside of the mentees’ home institutions.

We have identified some limitations of this program and analysis. Program participants may be self-selecting as almost 70% had prior CH mentors, most had prior research experiences, and some had been recipients of prior ASH awards. Outcomes were obtained from nonanonymous mentee and mentor surveys, mentee interviews, and a focus group, making these data vulnerable to self-reporting bias.25 For example, respondents may answer in a manner they think is socially desirable within the hematology community and may overstate the benefits of the program. The data could also be affected by sampling bias, because those who responded to surveys or volunteered to participate in the interview and focus group perhaps had a more impactful experience in the program. The mentees had an opportunity to participate in a free program, which may have led to overreporting positive aspects of the program. Finally, we had a relatively small sample size that affected our ability to detect statistically significant associations in our data. Although most participants completed the 1-year survey, there was a low rate of participation in the in-person interviews held at the ASH annual meeting (n = 2) and virtual focus group (n = 6). We attribute this to scheduling and time conflicts, because mentees who were unable to participate in these 2 sessions indicated they would be interested in speaking at a different time.

Our pilot program was positively received by most mentees and mentors, and continuing future cycles of this program may benefit even more trainees. We will continue to assign H/O fellows to external mentors that we predict will be a good fit, because quality of pairing positively affected mentee experience. We hope to recruit mentors who participated in this pilot program, faculty who were not matched with a trainee for the pilot program but indicated interest in participating and mentees from the pilot program who are now faculty. Communication frequency of at least once a month was favorable, and we will also include structured guidelines and scheduled check-ins for future cycles to help improve communication. To strengthen mentoring relationships, increase the opportunity for networking, and foster a sense of community within CH, we envision incorporating at least 1 in-person opportunity for participants. Expanding and refining this program will result in an increased number of external mentorship opportunities in CH with the goal to increase retention of trainees in the field.

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.P. conceived and implemented the mentorship program; S.J.P., A.A.K., and Z.Q. designed evaluation surveys; S.J.P., Z.Q., and I.W.-S. conducted interviews with mentees; S.J.P. and Z.Q. conducted a virtual focus group with mentees; S.J.P., Z.Q., and P.N. participated in data collection and organization; S.K.V. and Z.Q. performed statistical analysis; Z.Q. and P.N. performed content analysis of qualitative data; Z.Q. wrote the manuscript; Z.Q., P.N., and S.K.V. created figures and tables; P.N. created the visual abstract; and all authors reviewed the analysis and final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.T.C. is a consultant for Takeda; participates in advisory boards for Takeda, Genentech, Sanofi, and Medzown; has equity in Medzown; and receives honoraria/travel support from Octapharma. A.v.D. has received honoraria for participating in scientific advisory board panels, consulting, and speaking engagements from BioMarin, Regeneron, Pfizer, Bioverativ/Sanofi, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Precision Medicine, Sparx Therapeutics, Takeda, Genentech, and uniQure; and is a cofounder and member of the board of directors of Hematherix LLC, a biotech company that is developing superFVa therapy for bleeding complications. R.L.Z. is a consultant and stockholder for Triveni Bio. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Soo J. Park, University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center, 3855 Health Sciences Dr, MC-0987, La Jolla, CA 92037; email: sjp047@health.ucsd.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented in abstract form at the 64th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, 11 December 2022.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Soo J. Park (sjp047@health.ucsd.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.