Key Points

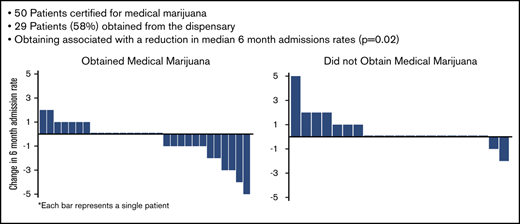

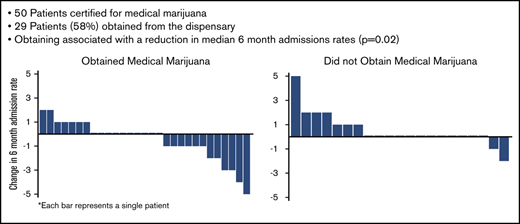

Fifty patients received certification for medical marijuana, whereas 29 (58%) obtained it from the dispensary.

Obtaining medical marijuana was associated with a reduction in admission rate and an increase in use of edible cannabis products.

Abstract

More than one-third of adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) report using cannabis-based products. Many states list SCD or pain as qualifying conditions for medical marijuana, but there are few data to guide practitioners whether or whom should be certified. We postulated that certifying SCD patients may lead to a reduction in opioid use and/or health care utilization. Furthermore, we sought to identify clinical characteristics of patients who would request this intervention. Retrospective data obtained over the study period included rates of health care and opioid utilization for 6 months before certification and after certification. Patients who were certified but failed to obtain medical marijuana were compared with those who obtained it. Patients who were certified were invited to participate in a survey regarding their reasons for and thoughts on certification. Patients who were certified for medical marijuana were compared with 25 random patients who did not request certification. Fifty adults with SCD were certified for medical marijuana and 29 obtained it. Patients who obtained medical marijuana experienced a decrease in admission rates compared with those who did not and increased use of edible cannabis products. Neither group had changes in opioid use. Patients who were certified for medical marijuana had higher rates of baseline opioid use and illicit cannabis use compared with those who did not request certification. Most patients with SCD who requested medical marijuana were already using cannabis illicitly. Obtaining medical marijuana decreased inpatient hospitalizations.

Introduction

Pain in sickle cell disease (SCD) is the main cause of poor quality of life and the most common reason for hospital admission in those with SCD.1,2 There is a critical need for improved treatments for both acute and chronic pain for people with SCD.1,2 The opioid crisis has emphasized the importance of nonopioid alternatives for pain treatment, including cannabis and cannabinoid-based products, but there is a need for more clinical data.3-6 Medical marijuana is legal in many states, but there are few data to guide practitioners in states with medical marijuana laws that list either SCD or pain as qualifying conditions as to whether they should certify patients with SCD for medical marijuana and how to select best candidates.6,7

Previous studies have examined cannabinoid-based products for the treatment of pain in conditions other than SCD, and systematic reviews have concluded that cannabis and cannabinoid-based products are effective for the treatment of chronic and neuropathic pain.7-9 Preclinical evidence in SCD mouse models demonstrates that cannabinoid receptor agonists are effective for the treatment of SCD pain.10,11 Finally, patient surveys obtained in several US and Jamaican SCD populations, including our own, have shown that more than one-third of adults with SCD report using illicit cannabis, primarily for pain treatment.12-14 However, to our knowledge, there are no published controlled studies of cannabinoid-based products for the treatment of pain in SCD.

Connecticut included SCD as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana in 2016. Medical marijuana may contain multiple cannabinoids including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD), or both, as well as terpenes, which affect smell and flavor.15 It can be purchased as bud/leaf/flower (dried plant that is often smoked), cartridges for vape pens, capsules or baked edibles, extracts, topicals, and more.15 Effect varies based on cannabinoid content and mode of use.16 Because medical marijuana is federally regulated, physicians cannot prescribe it; instead, they can certify that a patient has a qualifying condition with the state. Decisions about medical marijuana use are made between the patient, the state, and the dispensary.17 We considered the lack of controlled data and the health risks associated with some cannabinoid-based products. We also considered the variations in products and lack of data to guide product decisions. We knew that ∼40% of our patients were already using illicit cannabis to treat pain and other symptoms.12 Illicit cannabis is not regulated, so quality and potency are variable, and illicit cannabis can be contaminated with dangerous products including anticoagulants and infectious fungi.9-12,14-19 The majority of our patients self-identify as black, and although black people do not use illicit cannabis at higher rates than white people, they are 4 times more likely to be arrested for possession.20 We decided to certify patients with the rationale that it would allow illicit cannabis users to access a legal and safer cannabis product.

Here, we seek to evaluate the effect(s) of certifying patients with SCD for medical marijuana. Our primary outcome measure was to evaluate if obtaining medical marijuana was associated with changes in health care utilization and/or opioids dispensed. We also examined if patients who were certified for medical marijuana differed from those who were not certified. To evaluate the barriers to obtaining medical marijuana, we compared patients who obtained medical marijuana with those who were certified but did not obtain it. To evaluate differences between those certified for medical marijuana to other patients at our clinic, we compared all patients who were certified to a random selection of patients also seen at our clinic who did not request certification. Finally, we surveyed patients certified for medical marijuana to explore their motivation for requesting certification and to determine how the patients felt about medical marijuana compared with illicit cannabis. We hypothesized that obtaining medical marijuana would be associated with a reduction in health care and/or opioid utilization.

Methods

Effects of medical marijuana certification

Study design.

The study was approved by the Yale University institutional review board. This was a retrospective study done at an urban academic medical center with an adult sickle cell program. Starting in June 2016, we informed all patients seen at our clinic that SCD was now a qualifying condition for medical marijuana certification in our state. We offered certification to all patients regardless of health care or opioid utilization, except for those with a history of psychosis or controlled substance diversion.21 We examined data from 1 June 2016 to 1 June 2018. Clinical and opioid utilization data for patients seen at our center were obtained using our electronic medical record (EMR). Data on medical marijuana and opioid use were obtained using the Connecticut Prescription Monitoring and Reporting System (CPMRS). Patients who obtained medical marijuana were identified when CPMRS reported medical marijuana products were dispensed. Patients were considered in the certified but “did not obtain” group if they were certified in CPMRS but were never reported to have obtained a medical marijuana card or to have medical marijuana products dispensed. Control patients who were not certified were identified using a random number table; to be eligible for inclusion, these control patients must have been seen during the study period at our clinic at least twice. We did not match controls for clinical characteristics such as age, sex, or genotype because our goal was to assess if there were any characteristics which correlated with being certified for or obtaining medical marijuana.

Primary outcome.

Our primary outcome was change in health care utilization and/or opioids dispensation. Health care utilization data obtained included number of inpatient hospitalizations, number of emergency room visits not resulting in admission, and number of infusion center visits for pain crisis at our center. Opioids dispensed were reported as average daily oral morphine equivalents. For patients who obtained medical marijuana, we compared outcomes from 6 months before the date of the first reported episode of medical marijuana products dispensed in CPMRS to 6 months after this date. For patients who did not obtain medical marijuana, we compared outcomes from 6 months before the date of certification to 6 months after the date of certification.

Secondary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes obtained included: age, sex, SCD genotype (HbSS/HbSBthal0 or HbSC/HbSBthal+) hydroxyurea use, defined as whether an active hydroxyurea prescription was present in the EMR, insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, uninsured); previous cannabis use, defined as a previous urine toxicology positive for cannabinoids at any time in our EMR; l-glutamine use, defined as an active l-glutamine prescription presented in the EMR; and baseline health care and opioid utilization in the 6 months before either obtaining medical marijuana, being certified for medical marijuana, or in the middle of the study period for those who were not certified. All patients seen in our clinic are subject to random urine toxicology. Before 2018, CPMRS reported all medical marijuana products dispensed as “medical marijuana product”; therefore, it was not possible to evaluate the exact type of product dispensed during the study period. After June 2018, products dispensed were individually identified and characterized by name, mode of use of (edible, inhalation, topical, capsule), and cannabinoid content (THC, CBD, other).

Analytical plan.

Comparisons of the primary outcomes between those who were certified for medical marijuana (those who obtained medical marijuana and those who did not obtain medical marijuana), and those who did not request certification for medical marijuana were done using pairwise difference in differences analysis. Comparisons of all secondary outcomes were done using Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by Mann-Whitney U tests for all nonparametric data and analysis of variance followed by pairwise Student t tests for all parametric data. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were done using Stata statistical software package V15.1.

Survey study.

A survey created for this study was offered to all patients who presented to regularly scheduled clinic visits during the study period who had previously been certified for medical marijuana. Survey questions were read to participants and responses were recorded. All surveys were anonymized but patient demographics, including age and sex, were obtained. Patients were asked if they had previously used illicit cannabis and previous use was categorized by frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly). Questions regarding reasons for illicit cannabis use and method of illicit cannabis use were open-ended and all answers were recorded and then categorized. Patients were also asked whether they continued to use illicit cannabis after being certified for medical marijuana. Patients were asked if they had obtained medical marijuana, and, if so, frequency of use (daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly). Reasons for medical marijuana use and method of medical marijuana use were open-ended, and all answers were recorded and then categorized. Patients were asked how they thought medical marijuana effected their pain and their opioid use (more, less, no change, or do not know). For all questions regarding the comparisons of illicit cannabis to medical marijuana, subjects were asked to answer either agree, disagree, or do not know. A copy of the survey is shown in the supplemental Data (supplement 1).

Reasons for medical marijuana and illicit cannabis use, frequency of medical marijuana and illicit cannabis, and methods of medical marijuana and illicit cannabis use were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons of illicit cannabis and medical marijuana were described using descriptive statistics.

Role of the funding source.

The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Patient description

Fifty-two patients requested certification for medical marijuana between June 2016 and June 2018; we certified 50 of these patients. We denied certification to 2 patients because of a history of controlled substance diversion by them and their domestic partners. Of the certified patients, 29 (58%) obtained medical marijuana from a dispensary and 21 (42%) did not; these 2 sets of patients were grouped as “obtained” or “did not obtain” medical marijuana.

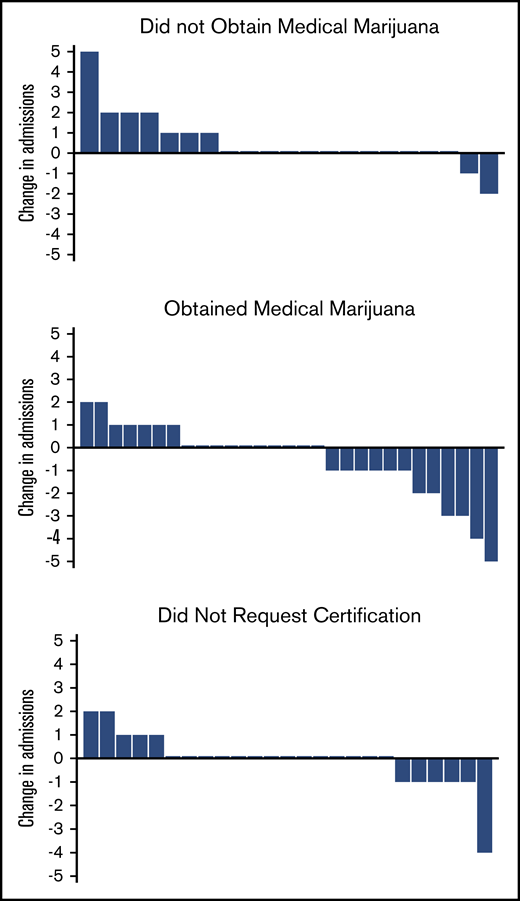

Obtaining medical marijuana was associated with a subsequent reduction in hospital admissions

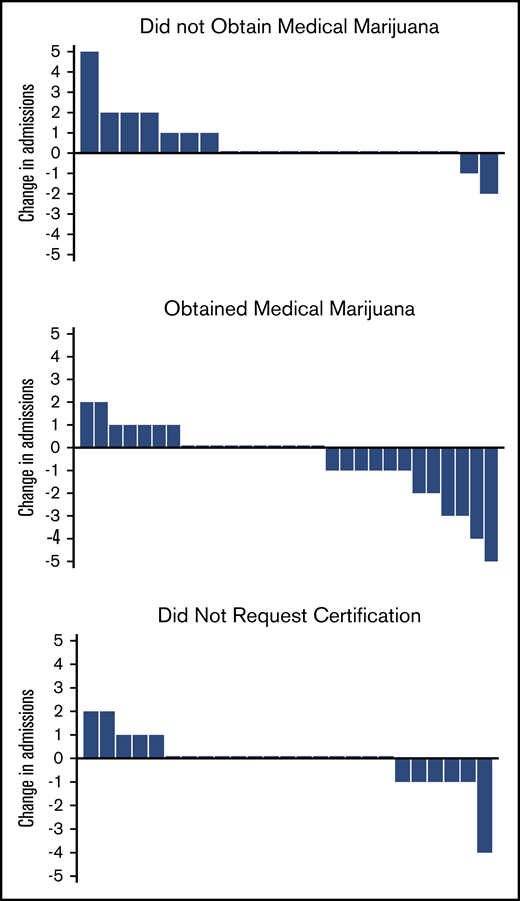

The patients who obtained medical marijuana showed a reduction in median 6-month hospital admissions compared with the patients who were certified but did not obtain medical marijuana (Table 1; Figure 1). Most changes in admissions were ±1, but in those who obtained medical marijuana, 2 patients reduced by 2, 2 patients by 3, 1 patient by 4, and 1 patient by 5, whereas in those who did not obtain, only 1 reduced admissions by 2 (Figure 1). There were no differences in emergency department (ED) or infusion center visits, total health care utilization, or opioids dispensed between the 2 groups, and the median change in opioids dispensed was 0 mg for both groups (Table 1).

Change in admission rates from baseline 6 months to 6 months after certification/obtaining medical marijuana. Each bar represents 1 patient. Positive change in admissions represents an increase in admissions compared with the previous 6 months; negative change represents a decrease; and 0 represents no change.

Change in admission rates from baseline 6 months to 6 months after certification/obtaining medical marijuana. Each bar represents 1 patient. Positive change in admissions represents an increase in admissions compared with the previous 6 months; negative change represents a decrease; and 0 represents no change.

Being certified for medical marijuana was associated with illicit cannabis use

We also randomly selected 25 patients who had not requested certification for medical marijuana; these control patients are grouped as “did not request.” There was no difference in age, sex, hydroxyurea use, or l-glutamine use among the 3 groups. Those who did not request certification were more likely to have private health insurance than those who were certified for but did not obtain medical marijuana (Table 1). Only 2 patients had no insurance, 1 who obtained medical marijuana and 1 who did not request certification; all others had either Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance. Only 2 patients started l-glutamine after medical marijuana certification, 1 who obtained medical marijuana and 1 who did not, and no patients started or stopped hydroxyurea during this period. Those who were certified but did not obtain medical marijuana were more likely to be HbSβ+/HbSC than either of the other 2 groups (Table 1). Patients who were certified for medical marijuana were more likely have had a previous urine toxicology test positive for cannabinoids than those who did not request medical marijuana certification (19/24, 79% [obtained] and 11/16, 69% [did not obtain] vs 1/17, 6%; P ≤ .001) (Table 1). All 3 groups had similar rates of admissions, ED use, and infusion center use in the prestudy baseline 6-month period (Table 1). Those who did not request medical marijuana certification had lower baseline median daily opioid use than either group who was certified for medical marijuana (0.6 mg vs 19.7 mg and 18.7 mg, P < .001 and P < .001).

Types of medical marijuana obtained by CPMRS

After certification, the median time to obtain medical marijuana was 114 days (interquartile range 57, 193). The CPMRS report from the year after the period ended (2019) showed 19/29 (65%) of the patients who had originally obtained medical marijuana were still accessing it. During that time, they obtained an average of 6.4 different products/patient (standard deviation 6.4), 93% obtained inhalable products, 60% obtained edible products, 7% obtained topical products, and 13% obtained capsules. All patients (100%) obtained products that contained THC, 28% obtained products that contained THC and CBD, and 72% obtained products that contained THC only.

Medical marijuana survey demographics

All patients seen in clinic after certification during the survey period were offered the opportunity to participate. Twenty-seven subjects were asked to participate in the survey, and 24 agreed. Twelve of 24 (50%) had obtained medical marijuana. There was no difference in age (29.7 ± 2.2 vs 36.2 ± 4.1, P = .2), sex (58% male vs 50% male, P = .7), previous home opioid use (88% vs 100%, P = .3), or prior lifetime marijuana use (75% vs 92%, P = .3) between survey subjects who did and did not obtain medical marijuana. The barrier that prevented obtaining medical marijuana was cost of application for 8 (66%) patients and difficulty completing the application for 4 (33%) patients.

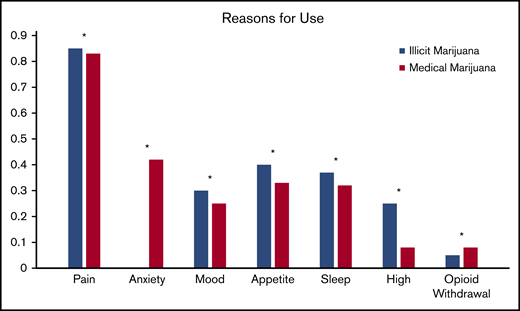

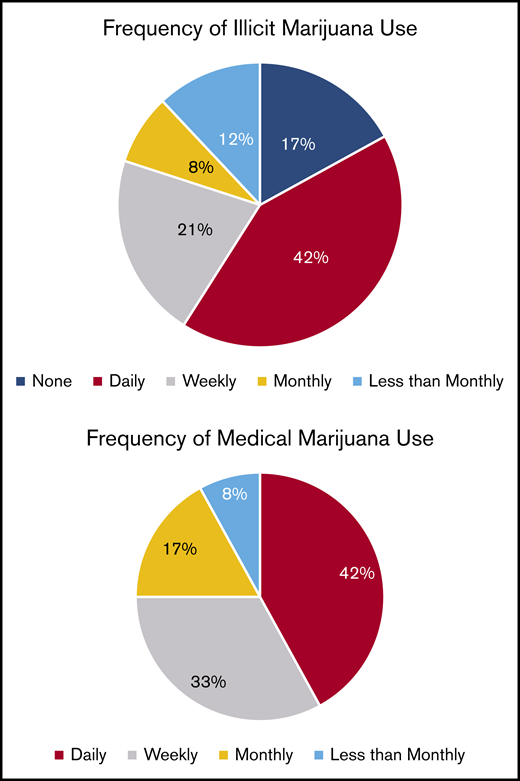

Reasons for obtaining medical marijuana and illicit marijuana and types obtained

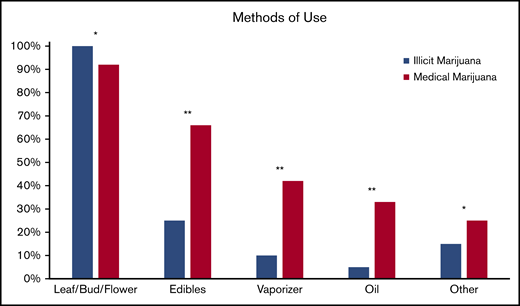

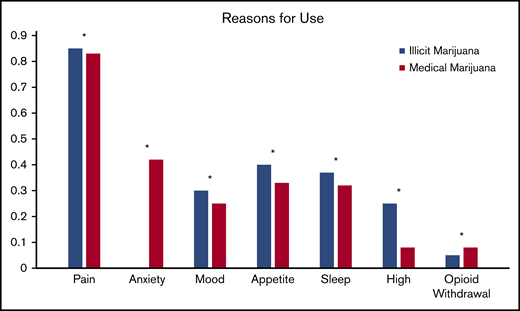

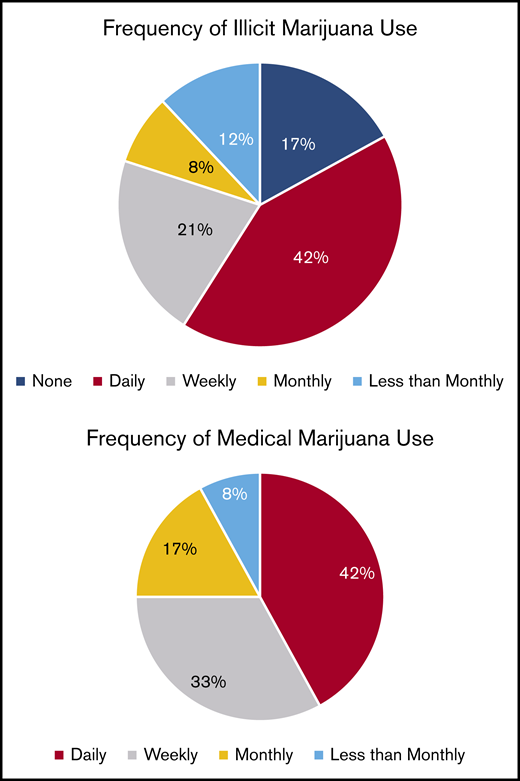

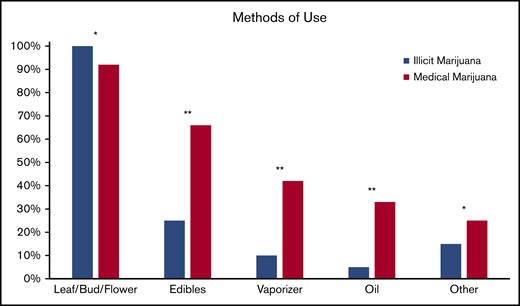

Pain relief was the most common reason for both illicit marijuana use and medical marijuana certification (85% and 83%, respectively; P = .9) and reasons were endorsed at a similar rate for illicit and medical marijuana use (Figure 2). Illicit marijuana and medical marijuana were used at a similar frequency (P = .3) (Figure 3), and specifically those who obtained medical marijuana did not change their individual frequency of use (P = .5) (supplement 2). The most common form of illicit marijuana use endorsed was leaf/bud/flower in 20/20 (100%). Bud use remained common among those who obtained medical marijuana 11/12 (92%), but they were more likely to also use ingested formulations, such as edibles and capsules than when they had used illicit cannabis (Figure 4).

Patient-reported reasons for using illicit cannabis and requesting medical marijuana certification. *P > .05.

Patient-reported reasons for using illicit cannabis and requesting medical marijuana certification. *P > .05.

Self-reported methods of illicit cannabis and medical marijuana use. Other forms listed include: dabs, sheets, teas, and tinctures. *P > .05, **P ≤ .05.

Self-reported methods of illicit cannabis and medical marijuana use. Other forms listed include: dabs, sheets, teas, and tinctures. *P > .05, **P ≤ .05.

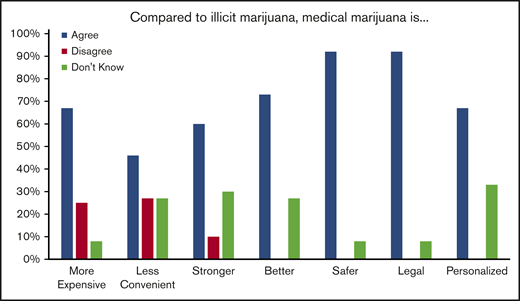

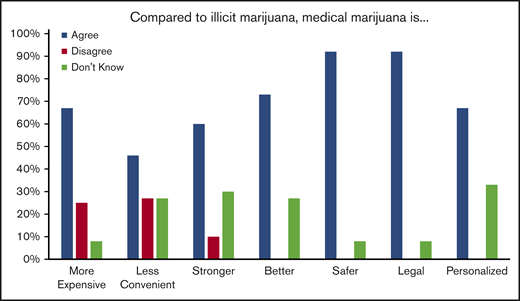

Opinions on medical marijuana and how it compares with illicit cannabis

After being certified for medical marijuana, 8/12 (66%) of those who did not obtain medical marijuana and 4/12 (33%) who did obtain medical marijuana stated they continued to use illicit marijuana that was “not from a dispensary.” Of those who obtained medical marijuana, 7/12 (58%) felt that medical marijuana was effective to treat their pain and 6/11 (54%) felt that medical marijuana allowed them to use less opioids. When asked to compare medical marijuana to illicit marijuana, most patients felt that medical marijuana was safer because it was less likely to be mixed with other substances and less likely to result in legal problems. Many also felt that it was stronger and better at controlling their symptoms. Of note, many reported that it was more expensive and less convenient to obtain than illicit marijuana (Figure 5).

Patient opinions regarding illicit cannabis compared with medical marijuana.

Discussion

There are few data to guide whether physicians in states with medical marijuana laws that list sickle cell disease or pain as qualifying conditions should certify patients with SCD for medical marijuana. Here, we describe our institution’s experience with certifying patients with SCD for medical marijuana and the effect of this on health care and opioid utilization. We found that most patients who requested medical marijuana were already using illicit marijuana. Obtaining medical marijuana was associated with a reduction in hospitalizations but no changes in ED or infusion center use. We also identified barriers that prevented some of our patients from using medical marijuana instead of illicit marijuana.

We considered why medical marijuana was associated with a reduction in admissions when previous illicit marijuana use was common and continued in some patients who did not obtain medical marijuana. We hypothesize that medical marijuana may be more effective for 2 possible reasons. First, it may be a higher quality product than illicit cannabis. States set regulations guiding the production of medical marijuana products so that they will be of consistent potency and free of contamination, whereas illicit products are unregulated.22 In our survey, patients reported they felt it was stronger and more effective for their symptoms. Second, that patients were more likely to use edible products compared with inhaled products when using medical marijuana. Inhaled products have a rapid but short onset of effect compared with edible products, where effects can last up to 8 hours and may improve pain control.23 Inhaled cannabis is also associated with an increase in pulmonary symptoms, which could increase health care utilization rates.24,25 Therefore, medical marijuana users may have caused a reduction in admission rates despite previous high rates of use because of possible improved efficacy over illicit cannabis. Further study should be done to evaluate this possibility.

Previous studies have shown that medical marijuana laws are associated with statewide reductions in opioid use, but we found that for patients with SCD medical marijuana was associated with no changes in opioids dispensed.26-29 This may be due to an “analgesic displacement effect.” Most admissions to the hospital for patients with SCD are for uncontrolled pain requiring hospital dispensed opioids.30 If medical marijuana allowed patients to tolerate previously intolerable pain at home, this could lead to more home opioids.31 Although admission rates were deceased, overall health care utilization rate was stable, suggesting that incidents requiring visits to a medical center (presumably mostly pain crisis) did not decrease, but that more of these could now be resolved at home. In a previous study, we found that daily users of illicit cannabis with SCD had fewer annual admissions than patients with similar pain, but had similar rates of opioids dispensed.32 The unique nature of chronic pain with pain crisis in SCD may explain why, in contrast to previous studies, we found medical marijuana was associated with no change in opioids dispensed, but a reduction in all-cause hospitalizations. Additionally, most of our patients with daily opioid use receive regular scheduled prescriptions, and we did not encourage them to change their regular doses. The relationship between marijuana and opioid use in SCD should be examined further in future studies.

We sought to understand why many patients were unable to access medical marijuana, and why some continued to occasionally use illicit cannabis despite accessing medical marijuana. Expense and convenience were both noted by patients as barriers. Expense includes a $100 annual registration fee and out-of-pocket costs for the products, which patients felt were more expensive in the dispensaries. During the time of our study, there was no dispensary located in the same town where our clinical facilities are located, and ride services available for clinical services are not available to visit a dispensary, so transport was also an issue. Race and socioeconomic status may also be barriers for patients with SCD. Medical marijuana use is more common among patients who are white and/or have higher incomes.33 Medical marijuana is associated with significant stigma, and patients with SCD already face stigma related to their disease and race, and thus may wish to avoid additional stigma from health care providers.33-35 Thus, there are multiple socioeconomic reasons obtaining medical marijuana may be particularly difficult for adults with SCD.

We decided to certify patients for medical marijuana in our clinic because we suspected that most patients who would request certification would already be illicit cannabis users, and we thought it would be safer to provide them with access to a regulated, legal substance. We considered the risk of adverse events related to cannabis use, including increased incidence of psychosis, intoxication, altered brain development in adolescence, and respiratory symptoms.36 Our study showed more than two-thirds of those who requested certification were previous cannabis users and did not use more frequently after certification. We had no new diagnoses of psychosis. One patient presented to the ED with altered mental status because of an accidental overdose after using a THC capsule; this emphasizes the need for guidance and education.37 Opioids and cannabinoids can have similar effects on mental status, and so there may be concern dual use would increase risk of overdose. However, states that pass medical marijuana laws have a reduction in admissions for opioid-related causes and no changes in admissions for marijuana-related causes.29 We had no admissions caused by opioid overdose during the study period. Larger studies should be performed to evaluate if medical marijuana is harm reductive compared with illicit cannabis, or if medical marijuana users experience different adverse effects than illicit cannabis users.

Ultimately, there is a need for larger controlled studies so that patients who may benefit from cannabis-based products can be given regulated pharmaceutical grade products with known effects, side effects, and drug interactions. Two such studies are ongoing, one that is studying an inhaled THC and CBD product for the treatment of chronic pain in SCD (NCT01771731) and one examining the feasibility of studying the oral US Food and Drug Administration approved product THC containing product dronabinol (NCT03978156). However, until such data are available to support the use of a specific pharmaceutical grade product, medical marijuana may offer patients who feel illicit cannabis treats their pain access to a legal product.

Our study has some limitations, including being a small, retrospective, single center study that may not be broadly applicable. We lack data on patient-reported outcomes such as pain and anxiety that may drive marijuana use. There is considerable variation among state medical marijuana laws, and so products that patients can access will vary both in terms of cannabinoid content and modes of use. We were unable to evaluate what cannabis products our patients were using during the period studied because our CPMRS only started releasing information about specific products dispensed to patients in June 2018. Products dispensed to patients were widely variable, so it was not possible for us to evaluate if certain products were more or less effective. Because our survey study was anonymous, we do not know which patients who did not obtain medical marijuana continued to use illicit marijuana and what products they used. We did not evaluate use of other illicit substances. We defined opioid use by opioids dispensed, but do not have data on opioids used. Finally, we do not know how either marijuana or opioid use may have changed during pain crisis.

In summary, our data show that obtaining medical marijuana for patients with SCD is associated with a reduction in admission rate and an increase in edible product use, but that many patients are unable to obtain medical marijuana. There is an urgent need for controlled studies to evaluate whether any cannabinoid-based medication can be effective for the treatment of pain or other symptoms in SCD.

Data will be made available through e-mails to the corresponding author at susanna.curtis@yale.edu.

Acknowledgments

S.A.C. is a student in the Investigative Medicine Program at Yale, which is supported by Clinical and Translational Science Awards (grant UL1 TR001863) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. This study is also supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 5T32HL007974-17).The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A.C. contributed to study design, protocol writing and development, data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript writing; D.L. contributed to data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript writing; J.S. contributed to study design, data acquisition, and manuscript writing; J.E.H. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing; C.P.M. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing; and J.D.R. contributed to study design, protocol writing and development, data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Susanna A. Curtis, Yale New Haven Hospital, 37 College St, Office #16, New Haven, CT 068510; e-mail: susanna.curtis@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.