Key Points

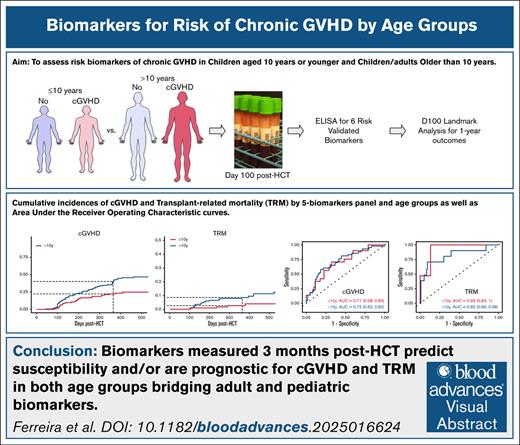

A day-100 5-biomarker panel predicts cGVHD (AUC: 0.71 ≤10 y; 0.72 >10 y).

A day-100 5-biomarker panel predicts TRM (AUC: 0.82–0.93), better in children ≤10 y.

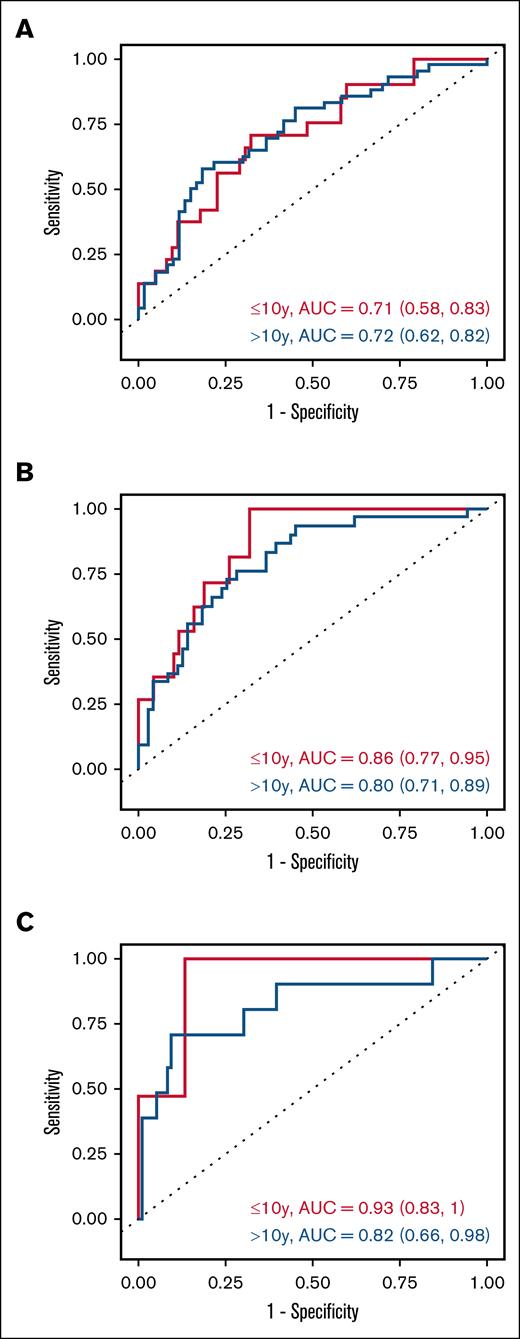

Visual Abstract

Assessment of risk biomarkers of chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in pediatric patients is lacking. We conducted a prospective study of 318 patients (129 children aged ≤10 years and 189 children/adults aged >10 years). Six plasma biomarkers (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 [CXCL9], interleukin-1 receptor-like 1 [IL1RL1], regenerating islet–derived 3-α [REG3α], matrix metallopeptidase-3 [MMP3], dickkopf-WNT signaling pathway inhibitor-3 [DKK3], and sCD163) were assessed at day 100 after HCT. We performed day-100 landmark analyses for cGVHD, stratifying at age ≤10 years vs >10 years and dichotomizing markers using the Youden index. IL1RL1 associated with future cGVHD in both age groups, as did DKK3. CXCL9, REG3α, and MMP3 are associated with cGVHD in patients aged >10 years. This 5-marker panel has an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.71 in children aged ≤10 years and 0.72 in children/adults aged >10 years for cGVHD risk, and an AUC of 0.86 in children aged ≤10 years and 0.80 in children/adults aged >10 years for moderate/severe cGVHD risk. A 5-biomarker panel (IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163) was associated with transplant-related mortality (TRM) in both age groups. Biomarkers measured 3 months post-HCT predict susceptibility and/or are prognostic for cGVHD and TRM in both children aged ≤10 years and children/adults aged >10 years, allowing for additional risk stratification.

Introduction

Blood and bone marrow malignancies represent approximately one-third of pediatric cancers and are the leading cause of pediatric cancer deaths.1 Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is the most potent immunotherapeutic treatment for these cancers. Furthermore, HCT is potentially curative for a range of inherited nonmalignant blood diseases.2 However, HCT efficacy has been impeded by clinically significant chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) affecting up to 50% of HCT recipients. cGVHD adversely affects life expectancy and quality of life and continues to be related to high transplant-related mortality (TRM) in both adults and children.3-6 The development of plasma cGVHD biomarkers5,7-11 has heightened interest in identifying measurable proteins that might provide meaningful information early before the occurrence of cGVHD. The recent National Institutes of Health cGVHD consensus series determined risk biomarkers to be a priority in enabling preemptive treatment.3,5,12-14 A risk marker is defined by the US Food and Drug BEST (biomarkers, end points, and other tools) recommendations as an assay that stratifies for the likelihood of developing disease in individuals who do not have clinically apparent disease.15 A recent study identified C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), matrix metallopeptidase-3 (MMP3), and dickkopf-WNT signaling pathway inhibitor-3 (DKK3) measured at 3 months after HCT as risk markers for cGVHD in 982 HCT recipients.11 Unfortunately, pediatric representation in this study was <10% and especially lacking in children aged ≤10 years. In a retrospective Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research study of 1117 children, factors associated with worse survival were age of >10 years, transplantation from a HLA partially matched or mismatched unrelated donor, advanced disease at HCT, and Karnofsky/Lansky performance status of <80.16 Furthermore, cGVHD is significantly associated with late effects after HCT in children.17 Additionally, the demarcation at 10 years seems to be meaningful for acute GVHD (aGVHD) biomarkers in this multicenter cohort.18 Therefore, age of >10 years being a major risk factor has raised speculation that informative biomarkers for risk of cGVHD might differ between younger children (aged <10 years) and children/adults aged >10 years.

To address this gap, we conducted a large prospective multicenter clinical trial to test previously validated risk cGVHD biomarkers11 in a predominantly pediatric cohort. Regenerating islet–derived 3-α (REG3α) is a biomarker for risk of gastrointestinal (GI) GVHD that was initially identified in aGVHD samples,19 and subsequently in adult patients with cGVHD and GI symptoms.20 Based on these studies,16,18 we used an age cutoff of 10 years and assessed 6 previously identified cGVHD plasma biomarkers (CXCL9, interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 [IL1RL1, previously ST2], REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and soluble CD163 [sCD163]) in 100-day post-HCT plasma to predict future occurrence of both cGVHD and TRM by landmark analysis.

Patients and methods

Study population

A total of 318 HCT recipients alive and with samples collected at day 100 after HCT were included from the larger multicenter prospective cohort (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02194439); 129 children aged ≤10 years and 189 individuals aged >10 years including both children and adults. All participants were followed up for at least 1 year. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at 6 centers: Children's National Medical Center, Texas Children's Hospital, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Boston Children’s, Johns Hopkins, and Indiana University. Adult patients were solely from 2 centers (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and Indiana University). Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians.

Samples preparation and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized overall and by age group using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and medians and ranges for continuous variables. Group comparisons of demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were performed using χ2 or Fisher exact test, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Biomarker concentrations were log2 transformed, to achieve approximate normality. Biomarker differences by age group were evaluated via Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and associations assessed using Spearman correlation. Biomarker associations with cGVHD and TRM were assessed using univariate Cox proportional hazard (CPH) regression and hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals reported. Biomarker predictive performance was evaluated based on time-dependent area under the curve (AUC) estimates derived from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.20 To avoid immortal time bias, a landmark analysis at day 100 was used and patients with events occurring before day-100 sample collection were excluded from the analysis. Marker thresholds were selected using the Youden index21 and used to dichotomize patients into groups of “high” and “low” biomarker values.

Given our cohort included both malignant and nonmalignant cases, and only patients with malignancies were at risk for a competing relapse event, cumulative incidences of cGVHD and TRM were analyzed under a cause-specific framework, with event times censored for patients experiencing relapse.22 Cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) for cGVHD and TRM were estimated as the complement of the Kaplan-Meier estimate.23 Separate CIFs were estimated for high and low biomarker values21-24 and age group. Log-rank testing was used to evaluate differences in CIFs between groups.

The classification performance of biomarker combinations was explored using a stepwise approach. Biomarkers demonstrating significant univariate associations were ranked by AUC, sequentially added to a CPH model, and used to construct time-dependent ROCs.24 For formal testing procedures, P values ≤.05 were considered significant. To evaluate robustness of results, P values from grouped tests evaluating multiple markers were adjusted using Bonferroni correction and reported in the supplemental Methods. Analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0 using the pROC and timeROC packages.

Results

Patient demographics

The characteristics of 318 patients accrued are shown in Table 1, stratified by aged of ≤10 years (40.6%) and >10 years (59.4%). Of the total cohort, 72% were pediatric patients, defined as having an age of ≤18 years. Compared with older patients, there was an overrepresentation of non-White/Hispanic (P = .03), nonmalignant disease (P < .001), marrow (P < .001), and prophylaxis with antithymocyte globulin (ATG)/alemtuzumab (P = .014) within the age of ≤10 years cohort.

Clinical outcomes

The cumulative incidence of cGVHD differed significantly between patients aged ≤10 years and those aged >10 years (supplemental Figure 1) with cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 1 year being 22.3% vs 40.2%, respectively. Because the older group included both children and adults, we further stratified this group into patients aged 11 to 18 years and those aged >18 years. Cumulative incidence of cGVHD persisted with older age groups (supplemental Figure 2). Similarly, the cumulative incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD was higher in the >10 year age group, with cumulative incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD at 1 year among those aged ≤10 vs >10 years being 11.8% and 29.1%, respectively (supplemental Figure 3), whereas cumulative incidence of TRM at 1 year being 2.6% and 8.5%, respectively (supplemental Figure 4).

Day-100 biomarkers

Median (interquartile range) log2 biomarker values are presented in supplemental Table 1. Significant differences in the distributions of IL1RL1 and MMP3 were noted between patients aged ≤10 and >10 years. Positive correlations were observed between IL1RL1 and MMP3 (ρ = 0.53) and DKK3 and MMP3 (ρ = 0.40; supplemental Figure 5). Supplemental Figure 6 shows boxplots of log2 biomarker concentrations by age group and cGVHD status. IL1RL1, MMP3, and DKK3 were significantly higher in patients aged >10 years who experienced cGVHD. Among patients aged ≤10 years, only IL1RL1 was significantly associated with cGVHD. Supplemental Figure 7 shows the distributions of biomarkers by age group independent of cGVHD status. IL1RL1 and MMP3 were significantly lower among those aged ≤10 years; other markers demonstrated no association with age.

Univariate landmark analysis of biomarker associations with cGVHD

Supplemental Table 2 summarizes marker associations with cGVHD based on day-100 landmark CPH models. Significant associations were observed in the overall cohort for IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, and DKK3. These same markers were significantly associated with cGVHD among patients aged >10 years. Similar trends were observed in patients aged ≤10 years.

Supplemental Table 3 shows marker associations with moderate/severe cGVHD, with significant associations and higher observed HRs in the overall cohort for IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, and DKK3. Significant associations with moderate/severe cGVHD were observed for IL1RL1 and DKK3 in both age groups. Among patients aged >10 years, REG3α and MMP3 were associated with moderate/severe cGVHD.

Marker performance for risk of cGVHD

Supplemental Table 4 summarizes biomarker classification performance for risk of cGVHD by 1 year after HCT. IL1RL1 displayed the strongest AUC of 0.69. Evaluating the selected IL1RL1 threshold within each age group resulted in sensitivity and specificity of 0.57 and 0.66, respectively, among patients aged ≤10 years, and 0.71 and 0.52, respectively, among patients aged >10 years.

For risk of moderate/severe cGVHD by 1 year after HCT, AUCs were generally larger than those for cGVHD. IL1RL1 again had the highest AUC of 0.77, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.66 and 0.80, respectively, in patients aged ≤10 years, and 0.61 and 0.76, respectively, in patients aged >10 years (supplemental Table 5). The AUC for DKK3 was 0.72, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.64 and 0.78, respectively, among patients aged ≤10 years, and 0.60 and 0.70, respectively, among those aged >10 years.

Day-100 landmark analyses of cGVHD by biomarker thresholds at day 100 after HCT by age group

Table 2 summarizes associations between cGVHD and day-100 biomarkers dichotomized at optimal thresholds. Among patients aged ≤10 years, the hazard of cGVHD was higher for IL1RL1 of >18 ng/mL (HR, 2.35; P = .03). Similar results were observed for IL1RL1 among patients aged >10 years. High REG3α and MMP3 were associated with cGVHD only in older patients (HR, 1.71; P = .04 and HR, 2.36; P = .003, respectively). DKK3 of ≥48 ng/mL resulted in a HR of 2.10 in patients aged >10 years (P = .01) and a HR of 2.39 in patients aged ≤10 years (P = .04).

Analyses restricted to cases of moderate/severe cGVHD (supplemental Table 6) demonstrated strong associations between IL1RL1 and the hazard of moderate/severe cGVHD in both patients aged ≤10 years (HR, 7.43; P = .001) and those aged >10 years (HR, 4.53; P < .001). Associations between REG3α (HR, 2.20; P = .01), MMP3 (HR, 2.81; P = .002), and DKK3 (HR, 3.40; P < .001) and moderate/severe cGVHD were significant in the older age group. Of note, sCD163 was also associated with moderate/severe cGVHD (HR, 2.38; P = .01) in patients aged >10 years. Among younger patients, only IL1RL1 mentioned earlier and DKK3 achieved a significant association (HR, 6.54; P = .01), although the other biomarkers of interest trended in this direction.

Multiplicity-adjusted P values are provided for day-100 landmark analyses of both cGVHD and moderate/severe cGVHD in supplemental Table 7.

Cumulative incidences of cGVHD by day-100 biomarker thresholds and by age group

The cumulative incidence of cGVHD differed significantly between patients with high and low IL1RL1 and DKK3 levels among those age ≤10 and >10 years (Figure 1). Among patients aged >10 years, there was a significant increase in the cumulative incidence of cGVHD for high CXCL9 (P = .04), REG3α (P = .04), and MMP3 (P = .002). Similar trends were observed among children aged ≤10 years.

Cumulative incidence curves of cGVHD by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 12 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 2; no cGVHD, n = 2) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 24; no cGVHD, n = 95), P = .095; >10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 7; no cGVHD, n = 5) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 55; no cGVHD, n = 101), P = .035. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 18 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 15; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .029; >10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 43; no cGVHD, n = 53) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 19; no cGVHD, n = 53), P = .006. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 50 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≥10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 14; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .11; >10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 35; no cGVHD, n = 43) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 27; no cGVHD, n = 63), P = .036. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 9 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 9; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 17; no cGVHD, n = 71), P = .50; >10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 46; no cGVHD, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 16; no cGVHD, n = 54), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 48 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 23) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 58), P = .036; >10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .009. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 620 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 5; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 18; no cGVHD, n = 55), P = .46; >10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 21; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 29; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .055.

Cumulative incidence curves of cGVHD by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 12 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 2; no cGVHD, n = 2) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 24; no cGVHD, n = 95), P = .095; >10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 7; no cGVHD, n = 5) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 55; no cGVHD, n = 101), P = .035. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 18 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 15; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .029; >10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 43; no cGVHD, n = 53) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 19; no cGVHD, n = 53), P = .006. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 50 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≥10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 14; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .11; >10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 35; no cGVHD, n = 43) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 27; no cGVHD, n = 63), P = .036. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 9 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 9; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 17; no cGVHD, n = 71), P = .50; >10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 46; no cGVHD, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 16; no cGVHD, n = 54), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 48 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 23) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 58), P = .036; >10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .009. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 620 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 5; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 18; no cGVHD, n = 55), P = .46; >10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 21; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 29; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .055.

The cumulative incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD differed significantly between those with high and low IL1RL1 and DKK3 levels in patients aged ≤10 years (P < .001 and P = .002, respectively) and those aged >10 years (P < .001 and P < .001, respectively; supplemental Figure 8). High levels of REG3α and MMP3 were significantly associated with increased cumulative incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD among older patients (P = .01 and P = .002, respectively), as were high levels of sCD163 (P = .01).

Multivariable day-100 landmark analyses of cGVHD by biomarker thresholds

In multivariable analyses, White/non-Hispanic vs not, malignant vs nonmalignant disease, marrow vs peripheral blood stem cells, GVHD prophylaxis (methotrexate/calcineurin inhibitors being the reference), and prophylactic ATG/alemtuzumab were included as covariates (Table 3).

After covariate adjustment, high IL1RL1 levels were significantly associated with cGVHD in patients aged >10 years (P = .01). High CXCL9 (P = .05), REG3α (P = .04), MMP3 (P = .01), DKK3 (P = .04), and sCD163 (P = .05) were also found to be associated with cGVHD in the older age group, whereas only high CXCL9 was found to be associated with cGVHD in the younger age group (P < .001).

Similar results were seen for moderate/severe cGVHD (supplemental Table 8), for which, among patients aged >10 years, high IL1RL1 (P < .001), REG3α (P = .004), MMP3 (P = .003), DKK3 (P < .001), and sCD163 (P = .02) were associated with moderate/severe cGVHD. Among patients aged ≤10 years, a significant association was seen between moderate/severe cGVHD and high levels of IL1RL1 (P = .01). After covariate adjustment, CXCL9 was significantly associated with moderate/severe cGVHD in the overall cohort (P = .03). Multiplicity-adjusted P values for multivariable analyses of cGVHD and moderate/severe cGVHD are provided in supplemental Table 7.

Performance of a 5-biomarker panel in risk prediction for 1-year post-HCT cGVHD

A 5-biomarker panel (CXCL9, IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, and DKK3) improved predictive performance of 1-year post-HCT cGVHD with an AUC of 0.73. In patients aged ≤10 years, the AUC was 0.71, and in patients aged >10 years the AUC was 0.72 (Figure 2A). Classification performance was likewise improved for moderate/severe cGVHD with an AUC of 0.82 overall, and 0.86 and 0.80 among younger and older patients, respectively (Figure 2B).

Area under receiver operator characteristics (AUROC) curve of biomarker panels. Panels in risk prediction for (A) cGVHD, (B) moderate/severe cGVHD, and (C) TRM at 1 year after HCT.

Area under receiver operator characteristics (AUROC) curve of biomarker panels. Panels in risk prediction for (A) cGVHD, (B) moderate/severe cGVHD, and (C) TRM at 1 year after HCT.

Univariate landmark analysis of biomarker associations with TRM

In patients aged >10 years, IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163 were significantly associated with TRM on landmark CPH analysis. Among patients aged ≤10 years, only IL1RL1 was significantly associated with TRM (supplemental Table 9).

Prognostic performance for 1-year TRM

Biomarker prognostic performance for 1-year TRM is summarized in supplemental Table 10. Overall, the strongest prognostic profile was observed for IL1RL1, with an AUC of 0.77, with sensitivity and specificity of 1 and 0.64, respectively, among patients aged ≤10 years, and 0.85 and 0.49, respectively, among those aged >10 years. For REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163, AUCs ranged from 0.69 to 0.76, with high specificity and reasonable sensitivity in both age groups across thresholds.

Among patients aged >10 years, TRM was significantly associated with higher IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163 based on landmark CPH analysis, with markers dichotomized at identified thresholds (supplemental Table 11). Specifically, the hazard of TRM was approximately fivefold higher for high IL1RL1 (HR, 4.85; P = .004), and as much as sevenfold higher for high concentrations of the others (HRs range from 6.41-7.13, all P values <.001). Similar trends were observed in those aged <10 years, although statistical significance was not achieved. Multiplicity-adjusted P values accounting for the evaluation of multiple biomarkers are provided in supplemental Table 12.

Cumulative incidence of TRM by day-100 biomarker thresholds and by age group

Dichotomizing each biomarker by the optimal thresholds selected for the overall cohort, cumulative incidence of post-HCT TRM differed significantly for high and low levels of IL1RL1 (P = .002), REG3α (P < .001), MMP3 (P < .001), DKK3 (P < .001), and sCD163 (P < .001) among patients aged >10 years (Figure 3). No statistical significance was seen in patients aged ≤10 years, possibly due to extremely low numbers of TRM events.

Cumulative incidence curves of TRM by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 7 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 0; no TRM, n = 11) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 109), P = .48; >10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 19) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 19; no TRM, n = 134), P = .21. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 20 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 45) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 75), P = .07; >10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 74) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 79), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 103 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 2; no TRM, n = 24) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 96), P = .36; >10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 13; no TRM, n = 21) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 132), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 14 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 21) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 99), P = .99; >10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 101), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 62 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 11) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 89), P = .51; >10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 20) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 6; no TRM, n = 111), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 789 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 10) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 90), P = .36; >10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 8; no TRM, n = 16) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 9; no TRM, n = 115), P < .001.

Cumulative incidence curves of TRM by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 7 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 0; no TRM, n = 11) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 109), P = .48; >10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 19) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 19; no TRM, n = 134), P = .21. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 20 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 45) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 75), P = .07; >10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 74) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 79), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 103 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 2; no TRM, n = 24) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 96), P = .36; >10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 13; no TRM, n = 21) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 132), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 14 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 21) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 99), P = .99; >10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 101), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 62 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 11) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 89), P = .51; >10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 20) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 6; no TRM, n = 111), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 789 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 10) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 90), P = .36; >10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 8; no TRM, n = 16) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 9; no TRM, n = 115), P < .001.

Multivariable day-100 landmark analyses of TRM by biomarker thresholds

High concentrations of IL1RL1 (P = .01), REG3α (P < .001), MMP3 (P = .002), DKK3 (P = .003), and sCD163 (P < .001) were significantly associated with TRM among patients aged >10 years on multivariable day-100 landmark CPH regression, with adjustment for race (White/non-Hispanic vs not), malignant vs nonmalignant disease, marrow vs peripheral blood stem cell graft, GVHD prophylaxis (methotrexate/calcineurin inhibitors being the reference), and prophylactic ATG/alemtuzumab (Table 4). Multiplicity-adjusted P values are provided in supplemental Table 12.

Performance of a 5-biomarker panel in risk prediction for 1-year TRM

Prediction of 1-year TRM based on a 5-biomarker (IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163) panel resulted in an AUC of 0.86. In patients aged ≤10 years, the AUC was 0.93, and in patients aged >10 years, the AUC was 0.82 (Figure 2C).

Discussion

In this study, we explored whether putative proteomic biomarkers previously assessed using HCT cohorts largely consisting of adults were applicable to children (National Institutes of Health definition as individuals aged ≤18 years), with a particular focus on children aged <10 years. We used 10 years as a cutoff based on the previous Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research study,16,18 and the kinetics of the immune system reconstitution after HCT in children.25,26 A study comparing a pediatric and adult cohort also showed differences in cGVHD organ involvement with higher GI involvement and lower lung and liver involvement in the pediatric population.27

Among the novel features in our study is the reliance on a prospective contemporary multicenter cohort with >400 HCT recipients, 70% of which comprised children aged ≤18 years.18 A total of 318 patients receiving HCT were alive at day 100 and had at least 1 sample at day 100 without aGVHD or cGVHD at the time of collection. Although incidence of aGVHD was similar in children aged ≤10 years and children/adults aged >10 years, the incidence of cGVHD was significantly increased by age group. TRM was extremely low in children aged <10 years.

The cohort is also unique because it has collected day-100 plasmas on most patients. With the exception of the ABLE study,10 ours is, to our knowledge, the first to examine the relevance of cGVHD risk biomarkers in pediatric HCT. We have relied on a cause-specific landmark approach to address our scientific aims. We chose day-100 post-HCT landmark and performed regression analyses at this time point. The advantage of this approach is to provide information on how patients’ current states affect their subsequent outcomes. The limitation is that it does require a large sample size due to the number of transitions between states that need to be captured.28,29 Our objective was to bridge pediatric and adult biomarkers of GVHD and therefore validate adult biomarkers in the pediatric population. We found, in this mostly pediatric cohort, that elevated levels of plasma proteins were risk factors of future cGVHD occurrence independent of clinical covariates, and prognostic for TRM. Five proteins (CXCL9, IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, and DKK3) as well as their composite panel were significantly associated with cGVHD and moderate/severe cGVHD and 5 proteins (IL1RL1, REG3α, MMP3, DKK3, and sCD163) as well as their composite panel were significantly associated with TRM in patients aged >10 years, whereas associations only trended toward significance in those aged ≤10 years.

In both age groups, elevations of day-100 IL1RL1 were significantly associated with greater cumulative incidence of cGVHD, moderate/severe cGVHD, and TRM, suggesting that despite low rates of cGVHD and TRM, particularly in patients aged ≤10 years, IL1RL1 was a strong cGVHD risk biomarker and 1-year TRM prognostic biomarker. Comparably, in 241 evaluable children from the ABLE study, day-100 IL1RL1 was also associated with cGVHD,10,27 as well as part of a 4-panel in 172 day-100 samples paired for cGVHD or no cGVHD in adult patients.9 However, in a recent large cohort of 987 all-adult HCT recipients with day-90/-100 samples, IL1RL1 was not a significant risk factor but was still the strongest prognostic marker for 1-year nonrelapse mortality.11 Soluble IL1RL1 (sIL1RL1), measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, entraps IL-33, limiting its availability to cytoprotective regulatory T cells expressing the membrane-bound form of IL1RL1 and worsening GVHD in preclinical models.30,31 sIL1RL1 concentrations in a well-characterized cohort of healthy participants have been shown to increase with age.32 We are not aware of any study of sIL1RL1 measurements in healthy children, but, in the context of GVHD, we have previously shown that IL1RL1 values before HCT and at day 7 after HCT, 2 timepoints occurring before alloreactivity is observed, were significantly lower in the ≤10 years age group; this was not the case for REG3α, another marker of aGVHD tested at these time points.18 In supplemental Figure 7, IL1RL1 values at day 100 after HCT were significantly lower in the ≤10 years age group as well as MMP3 plasma concentrations but not the other markers. Thus, there are 2 possible biological explanations for IL1RL1 being a more discriminative marker in the younger age group despite the small number of events: the intrinsic biology of the biomarker differing with age, and/or the role of IL1RL1 in the biology of GVHD. Indeed, we have shown in preclinical models of GVHD that sIL1RL1 is produced by alloreactive T cells, which dampen T helper 2 cell activity and shift T-cell polarization toward T helper 1 cell responses.30 T-cell output is age dependent, with higher output earlier in life.33 We have shown previously that viral antigen–specific T-cell responses correlate with decreased occurrence of GVHD and with younger age.34 If GVHD occurs, the biological response to GVHD treatment, particularly to corticosteroids, is better in younger patients, and corticosteroid use correlates with IL1RL1 in retrospective data.9 Unfortunately, we do not have samples to test this formally in this cohort but pharmacodynamic biomarkers are needed in these populations. Finally, we have shown previously using cause-specific landmark analysis in the subgroup of patients with malignant diseases and aged ≤10 years that IL1RL1 values provided a higher HR for prediction of TRM.18 These results suggest that IL1RL1 is more prognostic for TRM in patients aged ≤10 years, particularly in the subset of patients with malignancies.

CXCL9 has been validated as a strong risk biomarker for cGVHD and moderate/severe cGVHD in adult cohorts.9,11 In this study, in multivariable analyses, its association with cGVHD is significant in the overall cohort, in patients aged ≤10 years, and in patients aged >10 years. Comparatively, the ABLE study did not show association between CXCL9 and cGVHD, in either prepubertal children or pubertal children, whereas the association was found in an adult cohort.27 These differences suggest a potential age-related difference in the biology of cGVHD, although the weaker biomarker-biology correlation and the limited number of events observed in children may also be an explanation for some analyses lacking statistical significance.

REG3α levels were also associated with greater risk for cGVHD and 1-year TRM in children/adults aged >10 years. REG3α has been discovered and validated as a biomarker for GI GVHD.19 More recently, REG3α has been shown to significantly correlate with cGVHD but solely in adult patients with GI symptoms.20 Clinically, organs involved in patients affected by cGVHD vary with age, and a predominance of GI involvement, up to 39%, is found in the pediatric population,27 which may explain that high day-100 REG3α becomes significant as a systemic susceptibility biomarker for future cGVHD occurrence in this mostly pediatric population. However, the specific inference with GI symptoms is challenging to confirm here due to lack of organ specific cGVHD data in our deidentified database. Because REG3α values have not been shown to vary with age in healthy plasma nor in our cohort (supplemental Figure 7), the difference in the discriminatory capacity of REG3α, favoring the older group, is likely rooted in the biology of cGVHD in the GI tract such as differences in developmental maturity, metabolic function, and microbiota contained in the GI tract in the older group.35

Another remarkable finding in our study was the early elevation of markers implicated in fibrosis (DKK3, MMP3, and sCD163)36-38 in children who will develop moderate/severe cGVHD and TRM. Although this has recently been found in a large adult population,11 it has, to our knowledge, not been reported as associated with cGVHD in a pediatric population. All 3 markers are associated with cGVHD in the older group. The difference might be seen in this group because older age has been correlated with the extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrosis.39

Finally, sCD163, which is shed from the surface of inflammatory macrophages, was found associated with TRM in patients aged >10 years, and its effect in patients aged ≤10 years was not evaluable due to the low TRM incidence in this age group. In adults, sCD163 has been associated with cGVHD as early as 80 days after HCT40 and, recently, with nonrelapse mortality.11 Targeting macrophages with axatilimab in recurrent/refractory cGVHD has been successful,41 and inhibition of the CD163 inflammatory subset might result in a more specific targeting of macrophages during cGVHD.

There are some limitations to this study. In contrast to the aGVHD collection, only 1 sample at day 100 after HCT was available to study cGVHD, and because sampling was focused on aGVHD, collection of cGVHD characteristics were not as granular, particularly for organ involvement. The metrics we chose to compare models are only a subset of metrics used to evaluate biomarkers. The low number of events, particularly in the ≤10 years age group, precluded the derivation of training and validation sets.

From a clinical viewpoint, the ability to identify patients at high risk for cGVHD and TRM before the disease develops and treatment is given has possible important therapeutic implications ranging from preemptive treatment to close monitoring. Indeed, a blood test could serve as a rapid and accurate alternative to more invasive procedures, such as biopsies, representing a significant advance in cGVHD clinical monitoring. Furthermore, if we definitively validate these risk biomarkers of cGVHD and panels, we will be able to apply personalized medicine in future studies based on a rational and specific intervention. In the low-risk group, a randomized trial comparing rapid immunosuppression taper to no intervention could be proposed whereas in the high-risk group, it would permit early and accurate immunosuppressive treatment (ie, a steroid-free regimen including drugs spanning from JAK pathway inhibitors, extracorporeal photopheresis, and ROCK 2 inhibitor) before irreversible progression of the disease.

We conclude that noninvasive biomarker tests done as early as 3 months after HCT is a promising approach to identify children aged ≤10 years and children/adults aged >10 years who are at high risk for cGVHD and subsequent TRM. Our results beg the question whether day-100 biomarker-based preemptive interventions and improved monitoring strategies might decrease the risk of morbidity and death in this young population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinicians at all the institutions, who participated in accrual of samples. They thank all the data managers involved at all the sites for excellent management of the database and biobank as well as the Paczesny laboratory for helping with generating all the biomarkers values on thousands of samples.

The authors acknowledge the funding sources, including The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01HD074587), and the National Cancer Institute (grants R01CA168814 and R01CA264921). The project was supported, in part, by the Biostatistics Shared Resource, National Cancer Institute designated-Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina funded by the National Cancer Institute (grant P30 CA138313).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C.F. and E.H. were the study statisticians, conceived the statistical plan, and wrote the manuscript; D.D. performed samples retrieval and proteomics analysis; C.M.R., J.R., K.R.C., P.A.C., R.K., C.D., D.J., C.M.B., and C.R.Y.C. contributed to patient accrual, clinical data collection and quality assurance, research discussion, and the writing of the manuscript; and S.P. conceived and planned the study design, built and maintained the biorepository and biobank, performed and supervised proteomics experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.P. holds a patent on “Biomarkers and assays to detect chronic graft-versus-host disease” (US patent no. 10,571,478 B2) that has been licensed to Eurofins/Viracor. K.R.C. is on the advisory board of Jazz pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sophie Paczesny, Medical University of South Carolina, Hollings Cancer Center and Department of Immunology, 86 Jonathan Lucas St, Charleston, SC 29425; email: paczesns@musc.edu.

References

Author notes

Biomarker raw data are available through a material transfer agreement with Medical University of South Carolina and also through direct inquiries to the corresponding author, Sophie Paczesny (paczesns@musc.edu). All detection tools are available through commercial vendors. All data associated with this article are present within the article and/or in the supplemental Materials.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Cumulative incidence curves of cGVHD by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 12 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 2; no cGVHD, n = 2) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 24; no cGVHD, n = 95), P = .095; >10, high CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 7; no cGVHD, n = 5) vs low CXCL9 (cGVHD, n = 55; no cGVHD, n = 101), P = .035. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 18 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 15; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .029; >10, high IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 43; no cGVHD, n = 53) vs low IL1RL1 (cGVHD, n = 19; no cGVHD, n = 53), P = .006. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 50 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≥10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 14; no cGVHD, n = 36) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 61), P = .11; >10, high REG3α (cGVHD, n = 35; no cGVHD, n = 43) vs low REG3α (cGVHD, n = 27; no cGVHD, n = 63), P = .036. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 9 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 9; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 17; no cGVHD, n = 71), P = .50; >10, high MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 46; no cGVHD, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (cGVHD, n = 16; no cGVHD, n = 54), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 48 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 11; no cGVHD, n = 23) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 12; no cGVHD, n = 58), P = .036; >10, high DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low DKK3 (cGVHD, n = 25; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .009. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 620 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day +100; ≤10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 5; no cGVHD, n = 26) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 18; no cGVHD, n = 55), P = .46; >10, high sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 21; no cGVHD, n = 27) vs low sCD163 (cGVHD, n = 29; no cGVHD, n = 62), P = .055.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016624/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016624-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1770448607&Signature=q8TtqDqgWaJoTysWw82J2QgF0GtYoOleDLmcK5ezJoZIxihry1tPGm-~HS2arj6QbOABrukkLAYmSprZ4tjfQmGxxCPiFAkZC-R89PMB1~Rj2KLbpI~4KHgGSRFiL8KSTxfvQLqfzikBBmq5q9FzktewhPXQGtDYIgzrqmCqcK4poX1yuuLGd~tWi3xwkbxRtPv~sdMlYn-zb-toT~~hGRE~DLpEw-PTAHZpBOF2Ach~1s29hwNiog-wXyHbmDDJZhfZByvwMEzab6MJrOHZgb-nYNjCwhMcRyGua34~9KjimtGDBzgoHLTQ7KhdufKQVP6ChQGsvHm4ONbrhHlbfQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Cumulative incidence curves of TRM by day-100 biomarker thresholds and age group. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low CXCL9 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 7 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 0; no TRM, n = 11) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 109), P = .48; >10, high CXCL9 (TRM, n = 5; no TRM, n = 19) vs low CXCL9 (TRM, n = 19; no TRM, n = 134), P = .21. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low IL1RL1 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 20 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 45) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 75), P = .07; >10, high IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 74) vs low IL1RL1 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 79), P = .002. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low REG3α (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 103 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 2; no TRM, n = 24) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 96), P = .36; >10, high REG3α (TRM, n = 13; no TRM, n = 21) vs low REG3α (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 132), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low MMP3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 14 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 21) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 99), P = .99; >10, high MMP3 (TRM, n = 20; no TRM, n = 52) vs low MMP3 (TRM, n = 4; no TRM, n = 101), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low DKK3 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 62 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 11) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 89), P = .51; >10, high DKK3 (TRM, n = 11; no TRM, n = 20) vs low DKK3 (TRM, n = 6; no TRM, n = 111), P < .001. Curves comparing 4 groups: high vs low sCD163 (above [red] and below [blue] the threshold of 789 ng/mL, respectively) in either patients aged ≤10 years (solid line) or >10 years (dashed line), at post-HCT landmark day 100; ≤10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 1; no TRM, n = 10) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 3; no TRM, n = 90), P = .36; >10, high sCD163 (TRM, n = 8; no TRM, n = 16) vs low sCD163 (TRM, n = 9; no TRM, n = 115), P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016624/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016624-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1770448607&Signature=GkcHoC9ZSWe8Bunj804-OZ8NpvLR3aK~67S2svziSca~6PIpysRTYc8M6UoZ26Xw1Sofky6PAhprQ9As7YFYfUUwDnShyG8LgSdX5TW6YJKvKiYAT0Af22c75XKg~Sq1AiSt-QKm3ld49tiWvF3Vv7eQPvdhR-G6KxTILEYN7r4yjm4~yf1mufRKHiY2vdretzAIxtbUxn2E4Hk62mHP4j9x5lLV1t~6hyyfBLT31gOLNGrFUvZu4C2GCXL8AGTb8o5h2PwCYPIonn8m9xAPJt7J872q1ERtSKzeW-eSjtKIXTCYMBxxNOpNwV6g~iIxcjUBOcNWbNyIJ3kHnBR6kA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)