Abstract

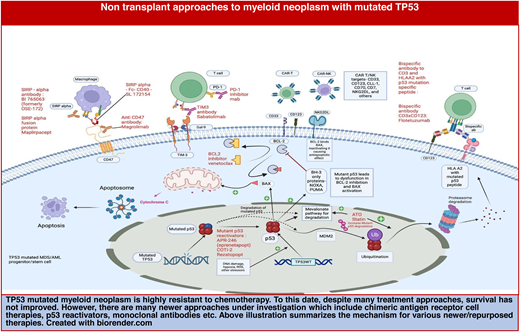

TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remain a challenging spectrum of clonal myeloid disease with poor prognosis. Recent studies have shown that in AML, MDS, and MDS/AML with biallelic TP53 loss, the TP53-mutated clone becomes dominant. These are highly aggressive diseases that are resistant to most chemotherapies. The latest 2022 International Consensus Classification categorizes these diseases under “myeloid disease with mutated TP53.” All treatment approaches have not improved survival rates for this disease. Many newer therapies are on the horizon, including chimeric antigen receptor T/NK-cell therapies, mutated p53 reactivators, Fc fusion protein, and monoclonal antibodies targeting various myeloid antigens. This review summarizes the current approaches for myeloid disease with TP53 mutation and provides an overview of emerging nontransplant approaches.

Learning Objectives

Understand that in International Consensus Classification classification, multi-hit TP53-mutated myeloid disease is 1 entity due to its universally aggressive course with poor prognosis

Acknowledge that current therapies have not improved outcomes in this high-risk disease

Recognize that while many approaches have failed, emerging nontransplant therapies have shown promise in preclinical and early clinical studies

CLINICAL CASE

A 67-year-old man with chronic anemia with hemoglobin of 9 to 10 gm/dl for the past 2 to 3 years presented with new-onset pancytopenia. Hgb was 6 gm/dl, platelet was 50 000/μL, and absolute neutrophil count was 800/μL; bone marrow biopsy showed myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with a blast count of 7%. Chromosome analysis showed complex karyotype without 17p alteration. NGS revealed 2 TP53 mutations with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 28% and 29%, respectively. The patient could not be enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with single-agent azacitidine. His platelet counts and transfusion requirements improved after 4 cycles followed by progression with recurrent cytopenia and increase in bone marrow blasts to 15% after 7 cycles.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and MDS are a continuum of a heterogeneous group of clonal myeloid disorders characterized by uncontrolled myeloid proliferation with impaired differentiation. With an evolving understanding of these diseases, genetic ontogeny is becoming critically important compared with clinical or histopathological subtype.1 In human cancers, the TP53 gene, located at 17p13.1, is the most commonly mutated gene. It functions as a tumor suppressor gene, commonly called the “guardian of the genome.” It encodes the p53 protein, a tetrameric transcription factor regulating the expression of multiple genes responsible for apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, stress response, and DNA damage response, among other key processes.2 Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with AML/MDS have a TP53 mutation. It is found in 20% to 30% of older patients and those with therapy-related disease.2,3 Prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy causes expansion of a preexisting TP53 mutated clone and increases subsequent risk for TP53-mutated AML/MDS later in life.4TP53 mutations are found in over 70% of cases with a complex karyotype (CK) and loss of 5/5q, 7/7q, or 17/17p.2 Similar to other malignancies with TP53 loss, TP53-mutated AML and MDS are challenging to treat, with a median survival of 5 to 10 months, irrespective of the therapy used.

Monoallelic and multi-hit TP53 mutations

An important distinction is between the mono- and biallelic TP53-mutated myeloid disease. In a study of 3324 patients, 378 patients with TP53-mutated MDS who had a detailed genetic characterization of alterations of TP53 locus and mapping of copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH) were divided in 4 TP53 mutant subgroups: (1) monoallelic mutation (33% of TP53-mutated patients); (2) multiple mutations without deletion or cnLOH affecting the TP53 locus (24%); (3) mutation(s) and concomitant deletion (22%); and (4) mutation(s) and concomitant cnLOH (21%). Additionally, in 24 patients the TP53 locus was affected by deletion, cnLOH, or isochromosome 17q rearrangement without evidence of TP53 mutations. Subgroup 1 was defined as monoallelic, and subgroups 2 through 4 were defined as multi-hit TP53-mutant disease. Clonality estimates of co-occurring mutations or allelic imbalances supported biallelic TP53 targeting in subgroups 2 through 4. This was validated in a subset of samples with phasing analysis or sequential sampling.5

Monoallelic cases were subclonal (median VAF = 13%) whereas in cases with multiple TP53 mutations, TP53-mutated clones were dominant (median VAF = 32%). Excluding chr17p, chromosomal aberrations were much more common with multi-hit cases compared with the monoallelic group. Ninety percent of monoallelic cases had at least 1 other driver point mutation. In comparison, 40% of all multi-hit TP53 cases had no other driver point mutation. Multi-hit patients had a higher blast count, higher risk subtypes, and severe cytopenias than monoallelic patients. The median overall survival for monoallelic patients (2.5 years) was closer to that of the wild-type TP53 patients (3.5 years), while patients with multi-hit disease had a much shorter median overall survival (OS) (8.7 months). Outcomes of monoallelic patients differed based on other co-mutations, and the higher VAF for the TP53 mutation correlated with worse survival, while this was not a major factor impacting universally poor outcomes in multi-hit patients.5

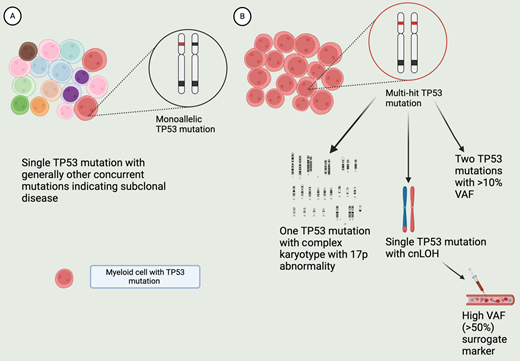

Figure 1 depicts key differences between monoallelic and multi-hit TP53-mutated MDS. In the latest World Health Organization classification, “MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation (MDS-biTP53)” has been added as a subcategory in MDS with defining genetic abnormalities. Any MDS with 2 or more TP53 mutations or 1 mutation with evidence for TP53-mutated copy number loss or cnLOH is included in MDS-biTP53. A single TP53 mutation with VAF >50% may be regarded as presumptive evidence for copy loss on the trans allele or cnLOH once a constitutional TP53 variant is ruled out.6

Features of monoallelic and multi-hit TP53-mutated MDS. A. MDS clone with monoallelic TP53 mutation. MDS with single mutation and low VAF (<10%) are considered monoallelic, with residual TP53 activity. The disease is dominated by non-TP53 mutated clones. This is generally a chemo-sensitive disease with better prognosis. B. Clone with multi-hit TP53 mutation, with minimal to no residual TP53 activity. This can occur from more than 1 TP53 mutation (VAF >10%), or 1 TP53 mutation along with chromosomal abnormality leading to loss of 17p locus, or with cn-LOH. A single TP53 mutation with high VAF (>50%) is a presumptive marker of cn-LOH or loss of trans allele. The clone with the TP53 loss becomes the dominant clone in this disease, generally lacking other driver mutations or chr abnormalities. Hence, the disease is chemo-refractory and associated with poor prognosis. Created with BioRender.com.

Features of monoallelic and multi-hit TP53-mutated MDS. A. MDS clone with monoallelic TP53 mutation. MDS with single mutation and low VAF (<10%) are considered monoallelic, with residual TP53 activity. The disease is dominated by non-TP53 mutated clones. This is generally a chemo-sensitive disease with better prognosis. B. Clone with multi-hit TP53 mutation, with minimal to no residual TP53 activity. This can occur from more than 1 TP53 mutation (VAF >10%), or 1 TP53 mutation along with chromosomal abnormality leading to loss of 17p locus, or with cn-LOH. A single TP53 mutation with high VAF (>50%) is a presumptive marker of cn-LOH or loss of trans allele. The clone with the TP53 loss becomes the dominant clone in this disease, generally lacking other driver mutations or chr abnormalities. Hence, the disease is chemo-refractory and associated with poor prognosis. Created with BioRender.com.

TP53-mutated MDS and AML—are they the same?

In a study of 2200 clinical trial participants with AML and MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB) by Grob et al,7 230 patients with a TP53 mutation were identified and classified into a monoallelic (n = 56) or biallelic state (n = 174). Biallelic state was defined as more than 1 TP53 mutation or TP53 mutation with loss of 17p locus or those with a single TP53 mutation with VAF >55%. The study found that the presence of TP53 mutation was associated with inferior OS regardless of MDS-EB or AML diagnosis. There was no difference in survival between MDS-EB and AML TP53-mutated cohorts. Interestingly, there was also no significant difference in survival between mono- and biallelic TP53-mutant cases; however, this could have been from the unavailability of high-quality DNA studies in monoallelic patients.7 Another retrospective study was completed in US centers with 299 patients with AML and MDS with CK, including 247 of these patients with TP53-mutated disease. There was no difference in survival between MDS (median OS, 13.0 months) vs AML (median OS, 9.4 months, P = .52) in the entire cohort. In MDS, the survival was vastly different when stratified by TP53 mutation status: no mutation (median, 36.5 months) vs TP53 monoallelic (median, 15.4 months) vs TP53 multi-hit (median, 10.2 months), P < .0001; and for TP53 monoallelic vs multi-hit, P = .02. For AML, OS in patients without a mutation was 23.2 months, significantly (P = .003) longer than in either TP53 monoallelic (median, 5.2 months) or TP53 multi-hit (median, 9.0 months), with no difference between 2 TP53 mutant categories, P = .68. OS between 81 de novo and 118 therapy-related myeloid disease trended toward inferior survival in therapy-related disease (p = 0.08). Within the TP53-mutated patients, there was no difference in survival between therapy-related and de novo disease (p = 0.19).8

Both of these studies demonstrate that the presence of multi-hit TP53 mutation, especially in the context of CK, supersedes MDS vs AML diagnosis and therapy relatedness.7,8 Since TP53- mutated AML/MDS are homogeneously aggressive diseases, in the latest International Consensus Classification from 2022, they are categorized under “myeloid neoplasm with mutated TP53.” This category includes multi-hit MDS or MDS with a single TP53 mutation with VAF >10% and CK with loss of 17p locus, and AML or MDS/AML with TP53 mutation (VAF >10%).9

Our patient has MDS with a blast count of approximately 7%, yet with 2 TP53 mutations he has multi-hit MDS and would be categorized as having TP53-mutated myeloid neoplasm.

Standard therapies for TP53-mutated myeloid disease

TP53-mutated myeloid disease is highly resistant to conventional chemotherapy, and most treatments developed so far have not improved survival (Table 1). Hence, patients with this disease should be strongly considered for clinical trial enrollment as stated in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for management of AML and MDS.

Summary of patient outcomes with TP53-mutated myeloid disease from select clinical trials

| Study (phase) experimental [E] and comparator arm [C] . | Patient population . | Sample size (all, TP53ma) . | Median age . | Sex (% female) . | CR (%)b (overall, TP53m) . | TP53 median VAF (%) . | Median OS (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 310,11,53 CPX-351[E] | 60-75 years with therapy-related AML/previous MDS or MDS karyotype including those pretreated with HMA | 153, 24 | 68 | 39 | 37, 29 | Overall: 9.33> (CI 6.37-11.86) TP53m: 4.53 | |

| 7 + 3 [C] | 156, 35 | 68 | 38 | 26, 34 | Overall: 5.95 (CI 4.99-7.75) TP53m: 5.13 | ||

| AML 19- Phase 3, randomized12 CPX-351 [E] | HR-MDS and AML | 105, 43 | 57 | 43 | 40 | TP53m: 7; TP53 WT: 28 Overall: 13.3 | |

| FLAG-Ida [C] | 82, 32 | 55 | 41 | 51 | Overall: 11.4 | ||

| Decitabine 10 days14 | MDS, AML, and relapsed AML MDS AML Relapsed AML | 116, 21 26, 9 54, 9 36, 3 | 74 | 41 | 53, 100 | TP53m: 12.7 TP53 WT: 15.4 | |

| Phase 2, randomized15 Decitabine 10 days [E] | AML ineligible for IC | 71, 24 43, 17 | 77 | 30, 41 | 50 | Overall: 6 (IQR 1 · 9-11 · 7); TP53m 4.9 (3 · 1-10 · 6) | |

| Decitabine 5 days [C] | 28, 7 | 78 | 29, 14 | 23 | Overall: 5.5 (IQR 2 · 1-11 · 7); TP53m 5.5 (IQR 1 · 9-8 · 5) | ||

| ASCERTAINh trial–phase 3, randomized16,17 Seq A: Oral dec C1 → IV dec C2 Seq B: IV dec C1 → oral dec C2 | Int or high-risk MDS CMML AML 20-30% blastsc | 133, 44 - BA 32%; MA 68% 66 67 | 70 72 | 36 33 | 25 | TP53m: 25.5 (BA: 13, MA: 29.2) TP53 WT: 33.7 | |

| VIALE A trial18-20 phase 3, randomized Azacitidine + venetoclax [E] | AML ineligible for intensive chemo | 431, 52 286, 38 | 76 | 40 | 66d, 55 | Overall: 14.7, 5.17e | |

| Azacitidine [C] | 145, 14 | 76 | 40 | 28, 0 | Overall: 9.6, 4.9 | ||

| Phase 1b27 Magrolimab + azacitidine | Untreated AML ineligible for IC | 87, 72 | 73 | 43 | 32, 32 | 61 | Overall: 10.8; TP53m: 9.8 |

| Phase 1b Magrolimab + azacitidine28 | Untreated MDS | 95, 25 | 69 | 35 | 33, 40 | 41 | Overall: NR; TP53m: 16.33 |

| Phase 1b/2 Eprenetapopt + azacitidine (2)33 | HMA naïve— TP53-mutated high-risk oligoblastic AML, MDS/AML, MDS and MDS/MPN, CMML | 55 | 66 | 53 | 44f | 21 | 10.8 (95% CI, 8.1 to 13.4) |

| Phase 2 Eprenetapopt + azacitidine34 | HMA-naïve TP53-mutated AML, MDS/AML, CMML | 52 | 74 | 48 | 57: MDS 36: AML | 23 | 12.1 (MDS) 10.4 (AML) |

| Phase 135 Eprenetapopt + venetoclax + azacitidine [E] | MDS previously transplanted or treated with HMA Untreated TP53-mutated AML | 49 (40 BA) 43 | 67 | 47 | 38 | 41 | 7.3 (95% CI 5 · 6-9 · 8) |

| Eprenetapopt + azacitidine [C] | 6 | 69 | 67 | 17 | |||

| Phase 1b38 Cohort A: tagraxofusp + AZA (MDS) Cohort B: tagraxofusp + AZA + ven (AML) 1L and RR Tagraxofusp + AZA + ven (AML) 1L only | New and R/R AML CD123 positive (declined/ ineligible for IC) HR-MDS for cohort A | 82 19 37 26, 13 (multi-hit TP53 m-9) | 62 70 71 | 37 41 39 | (69, 54)g | Overall: 14; TP53m: 9.5 | |

| MBG45341 Phase 1b Sabatolimab + HMA (decitabine or azacitidine) | Untreated HR/VHR MDS or CMML | 68, 14 | 70 (MDS) 68 (CMML) | 45 (MDS) 20 (CMML) | 20, 29 | Overall: 26.7 | |

| STIMULUS-MDS 1 Phase 2 Sabatolimab + HMA [E] | Untreated intermediate/high/very HR-MDS | 127, 41 65, 22 | 73 | 37 | 23 | Overall: 19 | |

| HMA alone [C] | 62, 19 | 73 | 27 | 21 | Overall: 18 | ||

| Phase 142,44 SL-172154 (19) SL-172154 + azacitidine (18) | R/R AML or MDS TP53m-MDS (for SL-AZA) | 37, 14 19 18 | 70 | 38 | 1 CR and 1 marrow CR in TP53m |

| Study (phase) experimental [E] and comparator arm [C] . | Patient population . | Sample size (all, TP53ma) . | Median age . | Sex (% female) . | CR (%)b (overall, TP53m) . | TP53 median VAF (%) . | Median OS (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 310,11,53 CPX-351[E] | 60-75 years with therapy-related AML/previous MDS or MDS karyotype including those pretreated with HMA | 153, 24 | 68 | 39 | 37, 29 | Overall: 9.33> (CI 6.37-11.86) TP53m: 4.53 | |

| 7 + 3 [C] | 156, 35 | 68 | 38 | 26, 34 | Overall: 5.95 (CI 4.99-7.75) TP53m: 5.13 | ||

| AML 19- Phase 3, randomized12 CPX-351 [E] | HR-MDS and AML | 105, 43 | 57 | 43 | 40 | TP53m: 7; TP53 WT: 28 Overall: 13.3 | |

| FLAG-Ida [C] | 82, 32 | 55 | 41 | 51 | Overall: 11.4 | ||

| Decitabine 10 days14 | MDS, AML, and relapsed AML MDS AML Relapsed AML | 116, 21 26, 9 54, 9 36, 3 | 74 | 41 | 53, 100 | TP53m: 12.7 TP53 WT: 15.4 | |

| Phase 2, randomized15 Decitabine 10 days [E] | AML ineligible for IC | 71, 24 43, 17 | 77 | 30, 41 | 50 | Overall: 6 (IQR 1 · 9-11 · 7); TP53m 4.9 (3 · 1-10 · 6) | |

| Decitabine 5 days [C] | 28, 7 | 78 | 29, 14 | 23 | Overall: 5.5 (IQR 2 · 1-11 · 7); TP53m 5.5 (IQR 1 · 9-8 · 5) | ||

| ASCERTAINh trial–phase 3, randomized16,17 Seq A: Oral dec C1 → IV dec C2 Seq B: IV dec C1 → oral dec C2 | Int or high-risk MDS CMML AML 20-30% blastsc | 133, 44 - BA 32%; MA 68% 66 67 | 70 72 | 36 33 | 25 | TP53m: 25.5 (BA: 13, MA: 29.2) TP53 WT: 33.7 | |

| VIALE A trial18-20 phase 3, randomized Azacitidine + venetoclax [E] | AML ineligible for intensive chemo | 431, 52 286, 38 | 76 | 40 | 66d, 55 | Overall: 14.7, 5.17e | |

| Azacitidine [C] | 145, 14 | 76 | 40 | 28, 0 | Overall: 9.6, 4.9 | ||

| Phase 1b27 Magrolimab + azacitidine | Untreated AML ineligible for IC | 87, 72 | 73 | 43 | 32, 32 | 61 | Overall: 10.8; TP53m: 9.8 |

| Phase 1b Magrolimab + azacitidine28 | Untreated MDS | 95, 25 | 69 | 35 | 33, 40 | 41 | Overall: NR; TP53m: 16.33 |

| Phase 1b/2 Eprenetapopt + azacitidine (2)33 | HMA naïve— TP53-mutated high-risk oligoblastic AML, MDS/AML, MDS and MDS/MPN, CMML | 55 | 66 | 53 | 44f | 21 | 10.8 (95% CI, 8.1 to 13.4) |

| Phase 2 Eprenetapopt + azacitidine34 | HMA-naïve TP53-mutated AML, MDS/AML, CMML | 52 | 74 | 48 | 57: MDS 36: AML | 23 | 12.1 (MDS) 10.4 (AML) |

| Phase 135 Eprenetapopt + venetoclax + azacitidine [E] | MDS previously transplanted or treated with HMA Untreated TP53-mutated AML | 49 (40 BA) 43 | 67 | 47 | 38 | 41 | 7.3 (95% CI 5 · 6-9 · 8) |

| Eprenetapopt + azacitidine [C] | 6 | 69 | 67 | 17 | |||

| Phase 1b38 Cohort A: tagraxofusp + AZA (MDS) Cohort B: tagraxofusp + AZA + ven (AML) 1L and RR Tagraxofusp + AZA + ven (AML) 1L only | New and R/R AML CD123 positive (declined/ ineligible for IC) HR-MDS for cohort A | 82 19 37 26, 13 (multi-hit TP53 m-9) | 62 70 71 | 37 41 39 | (69, 54)g | Overall: 14; TP53m: 9.5 | |

| MBG45341 Phase 1b Sabatolimab + HMA (decitabine or azacitidine) | Untreated HR/VHR MDS or CMML | 68, 14 | 70 (MDS) 68 (CMML) | 45 (MDS) 20 (CMML) | 20, 29 | Overall: 26.7 | |

| STIMULUS-MDS 1 Phase 2 Sabatolimab + HMA [E] | Untreated intermediate/high/very HR-MDS | 127, 41 65, 22 | 73 | 37 | 23 | Overall: 19 | |

| HMA alone [C] | 62, 19 | 73 | 27 | 21 | Overall: 18 | ||

| Phase 142,44 SL-172154 (19) SL-172154 + azacitidine (18) | R/R AML or MDS TP53m-MDS (for SL-AZA) | 37, 14 19 18 | 70 | 38 | 1 CR and 1 marrow CR in TP53m |

In some of the studies, all patients may not have undergone evaluation for TP53 mutation.

From among TP53-mutated patients, many studies do not report on allelic status of the TP53 mutation.

CR rates of the evaluable participants from the studies referenced. Reported CR could be best response, or response after a certain number of cycles.

Trial was designed to include AML 20% to 30% blasts patients; however, only CMML and MDS data are reported.

In this study, the reported values are composite CR, which includes CR and CRi; MRD positivity is a percentage of CR/CRi.

The study referenced reported cumulative median OS for TP53-mutated and poor-risk cytogenetics patients from VIALE-A trial and a phase 1b study with venetoclax and azacitidine.

47% are NGS negative CR from among the total evaluable 45 cases.

Includes CR/CRi or MLFS.

A study comparing oral ASTX727 (cedazuridine/decitabine) to IV decitabine.

AZA, azacitidine; BA, biallelic; CR, complete response; CRi, complete response with incomplete count recovery; dec, Decitabine; MA, monoallelic; MLFS, morphological leukemia free state; NA, not applicable; NR, not reached; 1R, first line; RR, relapsed refractory; TP53m, TP53 mutated; VAF, variant allele frequency; ven, venetoclax.

As with our patient, this may not always be possible. In such cases, standard therapies such as the use of intensive chemotherapy (IC), hypomethylating agents (HMAs), and venetoclax in TP53-mutated myeloid disease may be recommended.

Intensive chemotherapy

For TP53-mutated AML, standard chemotherapy has been largely ineffective. A phase 3 trial enriched in patients with high-risk AML in older adults, including those with therapy-related AML and antecedent myeloid disease, compared liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine (CPX-351) with conventional 7 + 3. While this study showed improved response rates, survival (median OS 9.33 months; 95% CI 6·37-11 · 86 vs 5.95 months; CI 4 . 99-7 . 75), and transplant outcomes with CPX-351 in the overall population, a subgroup analysis of TP53-mutated cases showed that the median survival was poor at 4.53 months with CPX-351, similar to 5.13 months with 7 + 3, and more patients (31% vs 13%) underwent stem cell transplant, with 7 + 3 in the TP53-mutated subgroup.10,11 Another study compared FLAG-Ida with CPX-351 in younger adults with adverse-risk MDS/AML and showed no difference in survival in the cohort (13.3 months CPX-351 vs 11.4 months FLAG-Ida); the median OS was only 7 months in the TP53-mutated subgroup, and there was no significant difference between the 2 treatment arms.12

Hypomethylating agents

For high-risk MDS, the current first-line therapy includes hypomethylating agents (HMAs), such as azacitidine or decitabine.2 Among patients with high-risk MDS treated with HMAs, TP53-mutated patients have a complete response (CR) rate of about 20% to 30% and an overall response rate (ORR) of 40% to 50%, similar to the wt-TP53. However, this does not translate into extended survival, with the median OS of 8 to 12 months in TP53-mutated patients, compared with >20 months of median OS in wt-TP53 patients.13 A single-institution trial of 10-day decitabine in higher-risk MDS (HR-MDS) and AML reported a remarkable ORR of 100% in TP53-mutated patients.14 This led to a phase 2 randomized trial comparing 5-day and 10-day decitabine regimens in older AML patients; CR rates were approximately 30%, and median OS was 5 to 6 months in both arms. There was no significant difference between TP53- mutated and wt-TP53 patients.15

In a recent crossover, phase 3 randomized study, an oral regimen of decitabine–cedazuridine was compared with intravenous decitabine in MDS or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) patients (ASCERTAIN trial); the study showed an encouraging median OS of 31.8 months in the cohort. A genetic subgroup analysis of this study showed a median OS of 25.5 months in the TP53-mutated group compared with 33.7 months in the wt-TP53 group. This is encouraging considering the higher median OS than has been reported previously in the TP53-mutated population (approximately 8 months). In this study, the biallelic TP53-mutated patients had a shorter median OS of 13 months compared with a median OS of 29.2 months in the monoallelic group.16,17

Venetoclax

Venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor, has shown promise in AML when combined with HMA, translating into a significant shift in the management of older AML patients unfit for chemotherapy. In the phase 3 VIALE-A trial, a combination of venetoclax with azacitidine improved survival from 9.6 months in the azacitidine-only group to 14.7 months. The CR rates were encouraging for the TP53-mutated subgroup—about 55% compared with 0% in the azacitidine group. However, in patients achieving CR, TP53-mutated patients (13% vs approximately 42% in the cohort) had comparatively fewer MRD-negative remissions.18,19 Consequently, achievement of CR was not associated with improved survival, as only 8% of those who achieved CR in the TP53-mutated subgroup survived >24 months compared with 34% in the cohort. In a follow-up pooled analysis of poor- and intermediate-risk cytogenetics in patients with AML from VIALE-A and the preceding single-arm phase 1b study of HMA/venetoclax, the median survival for TP53-mutated (with poor-risk cytogenetics) patients on venetoclax + azacitidine and azacitidine only was 5.17 months (CI 2.17-6.83) and 4.9 months (CI 2.14-9.30), respectively.19,20 Similar results were found when adding venetoclax to decitabine on a 10-day treatment schedule.21 These results corroborate in vitro studies demonstrating venetoclax resistance in TP53-mutated AML cells and in vivo studies showing decreased survival of TP53-mutated leukemic mice.22 Venetoclax addition to HMA does not confer significant survival benefits in TP53-mutated patients and comes at a cost of higher myelosuppression.19,23

A recent metanalysis and systematic review comparing treatment outcomes among 12 studies for newly diagnosed treatment-naïve TP53-mutated AML showed that despite better response rates with HMA + VEN and IC, pooled median OS was poor across all 3 treatments: IC, 6.5 months; HMA + VEN, 6.2 months, and HMA 6.1 months.24

Novel and emerging treatments for TP53-mutated myeloid disease

Many new therapies are undergoing investigation in TP53- mutated AML (Tables 1 and 2), with high rates of failure in clinical trials. CD47 is highly expressed on tumor cells and forms a signaling complex with signal regulatory protein alpha on macrophages, preventing macrophage-mediated phagocytosis.25 Azacitidine has been shown to increase CD47 expression on tumor cells, and in combination with the anti-CD47-blocking antibody magrolimab, it increased the phagocytosis of malignant myeloid cells in the in vitro and in vivo AML models.26 This led to phase 1b trials with magrolimab and azacitidine in untreated MDS and AML (ineligible for IC). They showed encouraging CR rates of 30% to 40%, with a median OS of 9.8 months in AML and approximately 16 months in MDS with TP53 mutation (Table 1).27,28 These early-phase studies led to randomized phase 3 trials ENHANCE, ENHANCE-2, and -3.29 ENHANCE compared magrolimab + azacitidine vs azacitidine alone in HR-MDS but was terminated for lack of improvement in OS compared with HMA alone. ENHANCE-2 compared physician's choice of either azacitidine + venetoclax or 7 + 3, with azacitidine + magrolimab in TP53-mutated AML; however, that study was stopped due to lack of OS benefit. ENHANCE-3 compared azacitidine + venetoclax with or without magrolimab in AML patients unfit for IC. The trial was terminated for lack of efficacy and about an 8% increased risk of adverse events leading to death in the magrolimab arm.30,31

Select ongoing trials including patients with myeloid neoplasm with mutated TP53

| Experimental drug . | Eligibility criteria . | Phase . | Primary outcome measures . | Secondary outcome measures . | Identifier . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrectinib + ASTX727 (cedazuridine + decitabine) | Relapsed/refractory TP53-mutated AML | 1 | Incidence of dose-limiting toxicities | Adverse events, response rates, EFS, OS, etc | NCT05396859 |

| Sodium stibogluconate | MDS and AML with TP53 mutation | 2 | Overall response rate | Adverse events | NCT04906031 |

| Decitabine + arsenic trioxide (ATO) | MDS and AML with TP53 mutation | 1 | Adverse effects | Response rates | NCT03855371 |

| SL172154 +/– azacitidine +/– venetoclax | HR-MDS and AML | 1 | Safety and tolerability Determine phase 2 dosing | Preliminary evidence for antitumor activity, PK | NCT05275439 |

| Sabatolimab + HMA (azacitidine/IV or oral decitabine) | HR-MDS | 2 | Treatment-emergent adverse events | CR, PFS, and OS, etc | NCT04878432 |

| Tagraxofusp +/– azacitidine | AML with prior HMA exposure | 2 | CR rate | PFS and OS, etc | NCT05442216 |

| Atorvastatin | Solid tumors and relapsed AML | 1 | Change in conformation of mutated p53 (IHC staining) | Change in caspase 3 Change in Ki-67 | NCT03560882 |

| Maplirpacept + azacitidine +/– venetoclax | Newly diagnosed AML and R/R MM/lymphoma | 1 | Safety | PK, response rates, DOR, and others | NCT03530683 |

| SAR443579 | Pediatric AML, B-ALL, HR-MDS, BPDCN | 1/2 | Toxicity CR rate | Dosing for expansion phase, adverse events, etc | NCT05086315 |

| Experimental drug . | Eligibility criteria . | Phase . | Primary outcome measures . | Secondary outcome measures . | Identifier . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrectinib + ASTX727 (cedazuridine + decitabine) | Relapsed/refractory TP53-mutated AML | 1 | Incidence of dose-limiting toxicities | Adverse events, response rates, EFS, OS, etc | NCT05396859 |

| Sodium stibogluconate | MDS and AML with TP53 mutation | 2 | Overall response rate | Adverse events | NCT04906031 |

| Decitabine + arsenic trioxide (ATO) | MDS and AML with TP53 mutation | 1 | Adverse effects | Response rates | NCT03855371 |

| SL172154 +/– azacitidine +/– venetoclax | HR-MDS and AML | 1 | Safety and tolerability Determine phase 2 dosing | Preliminary evidence for antitumor activity, PK | NCT05275439 |

| Sabatolimab + HMA (azacitidine/IV or oral decitabine) | HR-MDS | 2 | Treatment-emergent adverse events | CR, PFS, and OS, etc | NCT04878432 |

| Tagraxofusp +/– azacitidine | AML with prior HMA exposure | 2 | CR rate | PFS and OS, etc | NCT05442216 |

| Atorvastatin | Solid tumors and relapsed AML | 1 | Change in conformation of mutated p53 (IHC staining) | Change in caspase 3 Change in Ki-67 | NCT03560882 |

| Maplirpacept + azacitidine +/– venetoclax | Newly diagnosed AML and R/R MM/lymphoma | 1 | Safety | PK, response rates, DOR, and others | NCT03530683 |

| SAR443579 | Pediatric AML, B-ALL, HR-MDS, BPDCN | 1/2 | Toxicity CR rate | Dosing for expansion phase, adverse events, etc | NCT05086315 |

BPDCN, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm.

Another agent exploited in TP53-mutated AML was eprenetapopt (APR-246), which acts via reactivating p53 function in TP53-mutated cells. Eprenetapopt is a prodrug that is spontaneously converted to methylene quinuclidinone, which binds mutated p53 protein and leads to thermodynamic stabilization of the p53 protein. This was the first agent that impacted mutated p53 in preclinical studies and demonstrated clinical activity in early studies.32 In 2 phase 1/2 studies, eprenetapopt combined with azacitidine yielded an ORR of 33% and 71% in TP53-mutated AML/MDS patients, and both studies showed a median OS of 10 to 12 months.33,34 In a separate phase 1 study in TP53-mutated AML, the combination of eprenetapopt with venetoclax and eprenetapopt + venetoclax + azacitidine demonstrated CR/CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) rates of 33% and 56%, respectively.35 This promising preliminary activity in early studies failed to translate into a clinical benefit in a phase 3 trial comparing the combination of eprenetapopt with azacitidine to azacitidine alone in TP53-mutant MDS. The primary endpoint of this study, CR rate in the combination group was higher at 33% compared with 22% in the control but was not statistically significant.36

CD123 is expressed in myeloid progenitors, endothelial cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. It is not expressed on CD34+/CD38− hematopoietic cells, making it a promising target for many myeloid malignancies. Tagraxofusp (TAG) is a conjugate of subunit A of diphtheria toxin and a CD123 ligand, recombinant interleukin 3. The recombinant interleukin 3 component binds to CD123 and results in receptor internalization and intracellular release of diphtheria toxin, which inhibits ribosome-mediated protein synthesis.37 TAG has been FDA approved for the treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and has shown high remission rates with long-term disease-free survival. With the preclinical work showing synergy and reversal of TAG resistance with venetoclax or azacitidine, a phase 1b trial investigated efficacy and safety of TAG + azacitidine in AML or MDS and TAG + azacitidine + venetoclax in AML. In this study, TAG + azacitidine + venetoclax showed CR rates of 54% in TP53-mutated patients and survival of 9.5 months.38

Another emerging treatment undergoing investigation is sabatolimab—a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-3 (TIM-3). TIM-3 is an inhibitory surface receptor regulating innate and adaptive immune responses on leukemic stem cell (LSC). It also promotes LSC self-renewal through interaction with galectin-9.39 In preclinical studies, sabatolimab increased phagocytosis of TIM-3-expressing leukemic cells and interfered with the self-renewal of LSCs.40 In a phase 1b study, a combination of sabatolimab with HMA in patients with HR-MDS and CMML showed an ORR of approximately 60% with an approximately 20% CR.41 In TP53-mutated patients, the CR rate was approximately 25% (Table 1). However, a randomized phase 2 study comparing sabatolimab combination with HMA and HMA alone in MDS (STIMULUS-MDS 1) did not show significant differences in CR rates, progression-free survival (PFS), or OS between the 2 groups.42 Subsequently, a randomized phase 3 trial (STIMULUS-MDS 2) assessing the same regimen was discontinued.

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that CD40 signaling potentiates the antitumor activity exerted by blocking CD47/SIRPα blockade. SL-172154 is a hexameric bifunctional fusion protein that consists of SIRPα and CD40L domains linked through an inert Fc linker. SIRPα-Fc-CD40L binds to CD40 and CD47 with high affinity and leads to activation of the CD40 signaling without Fc receptor cross-linking. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that this effect is superior to isolated CD47 blocking or CD40 agonist activity.43 Preliminary results of an ongoing phase 1 trial of SL-172154 monotherapy and in combination with azacitidine in adults with relapsed/refractory (R/R) MDS or AML have demonstrated acceptable tolerance and biological activity in TP53-mutated disease (Table 1). Of 4 patients with untreated TP53-mutated AML in an SL-AZA cohort, 2 had marrow CR and CR and were bridged to allotransplant, and the other 2 had stable disease.44

In addition to the monoclonal antibodies, several promising cell therapies are under development. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies directed at myeloid antigens, including CD33, CD38, CD70, CD123, CD135, CLL1, NKG2D, Lewis Y, FLT3, and others are in early development. CLL1 is highly expressed on the AML LSC but not on hematopoietic stem cells, and hence is a potential target in the treatment of AML. While early studies with CLL1 and CD7 CAR-T have shown impressive CR rates in R/R AML, there are no studies reporting responses in TP53 MN with any of the CAR-T under development.45 Recent preclinical data indicating resistance of TP53-mutated AML to CAR T cell–mediated killing are concerning.46 Another strategy is to use universal CAR-T therapies that can be used with a variety of a short half-life target molecule that binds to the target antigen, enhancing its efficacy. Interruption of target molecule infusion quickly switches off CAR T-cell activity, limiting its toxicity.

T-cell engagers like blinatumomab and teclistamab have been breakthroughs in B-ALL and multiple myeloma, respectively. Many such T- and NK-cell engagers are being investigated in MDS/AML. Comparison of bone marrow biopsy samples between wt-TP53 and TP53-mutated patients has shown an inherently immunosuppressive and IFN-gamma-driven microenvironment in TP53-mutated AML, producing optimism for T-cell engagers. A post hoc analysis of a trial investigating flotetuzumab, a CD3 x CD123 bispecific antibody, in R/R AML showed promising activity in R/R TP53-mutated AML, with 47% CR rates.47,48

The last 40 years of research in TP53 has paved the way for mutation-specific and tumor-agnostic treatment options for patients with TP53-mutated malignancies. Rezatapopt (PC14586) is one such example, reactivating Y220C mutant TP53 to WT activity; it has shown acceptable tolerability and partial responses in advanced solid tumors.49 In vitro studies have shown limited apoptogenic activity with PC14586 in TP53-Y220C AML cells. However, when combined with XPO1, MDM2, and BCL2 inhibition, it induces massive apoptosis.50 These findings suggest the need to investigate the role of rezatapopt in combination with BCL2, XPO1, and MDM2 inhibitors in Y220C TP53- mutated MDS and AML.

Modulation of mutant p53 degradation is another strategy; atorvastatin has shown increased ubiquitin-mediated mutant p53 degradation in preclinical studies.51 It has also shown to reverse mevalonate pathway–mediated CAR-T resistance in TP53-mutated AML cells. It is currently undergoing further investigation in a phase 1 study.46

p53 is an intracellular protein, degraded by proteosome, and a fraction of its peptides are presented by HLA on the cell surface. In another mutation-specific approach, a CD3 bispecific antibody has been developed that binds to neoantigen and HLA A2 complex from degradation of a mutated p53R175H protein and leads to T-cell-mediated tumor killing. This approach has shown activity in in vivo and in vitro studies.52

In summary, TP53 myeloid neoplasm is a challenging disease, and most therapies have not improved survival. Despite this, there are many newer classes of therapies—cell therapies, T/NK-cell engagers, and modulators of p53 degradation—that are promising as we remain hopeful.

Our patient was eventually enrolled in a clinical trial after progression.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Ansh K. Mehta: no competing financial interests to declare.

Marina Konopleva: consulting fees from Syndax, Novartis, Servier, AbbVie, Menarini-Stemline Therapeutics, Adaptive, Dark Blue Therapeutics, MEI Pharma, Legend Biotech, Sanofi Aventis, Auxenion GmbH, Vincerx, Curis, Intellisphere, Janssen, Servier; advisory board membership for AbbVie, Auxenion GmbH, Dark Blue Therapeutics, Legend Biotech, MEI Pharma, and Menarini/Stemline Therapeutics; research funds from Klondike, AbbVie, and Janssen.

Off-label drug use

Ansh K. Mehta: Venetoclax.

Marina Konopleva: Venetoclax.