Abstract

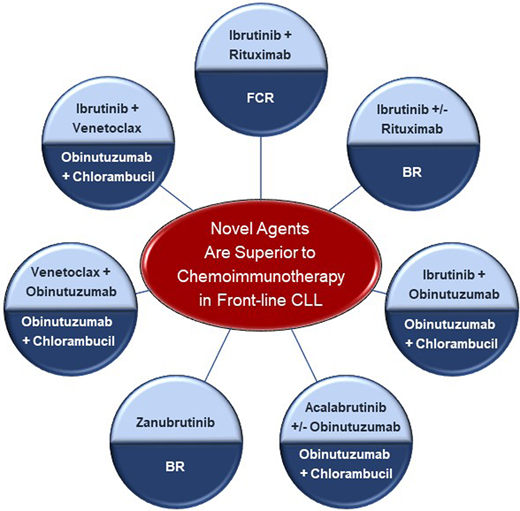

The treatment landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has evolved considerably over the past decade due to the development of effective novel agents with varying mechanisms of action, including Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors. Extrapolating upon the success of anti-CD20–directed chemoimmunotherapy, a dual-targeted approach has been explored in treatment-naive patients with CLL. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody combinations with BTK inhibitors as well as BCL2 inhibitors have demonstrated superiority over traditional cytotoxic chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab; bendamustine-rituximab; and obinutuzumab-chlorambucil. Impressive clinical benefit is seen in both younger and older patients, those with comorbidities, and, most importantly, those with poor prognostic features. Given this success, combinations of BTK inhibitors and venetoclax have been explored in clinical trials. These dual-targeted regimens provide remarkable efficacy while allowing for an all-oral approach and fixed duration of treatment. Current investigations under way are evaluating the utility of a triplet approach with the addition of obinutuzumab in comparison to a doublet approach.

Learning Objectives

Learn about the approved dual-targeted regimens for the frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Learn about Bruton tyrosine kinase and B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor combinations under investigation in frontline chronic lymphocytic leukemia

CLINICAL CASE

A 66-year-old man was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) after presenting with cholecystitis and was found to have a lymphocytosis of 54 × 103/µL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry demonstrated a monoclonal B-cell population with expression of CD5, CD20dim, and CD23 and λ light chain restriction; cyclin D1 and CD10 were negative. As other complete blood count (CBC) parameters were within normal limits and he was asymptomatic, he was monitored closely. After 4 years of watch and wait, his white blood cell count increased to 220 × 103/µL. He also developed worsening fatigue and progressive anemia with a hemoglobin of 9.7 g/dL. Prognostic testing identified del(13q) by fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV) somatic hypermutation at 5.8%. He presents to discuss potential treatment options. You share that a number of targeted therapies have been approved for the treatment of CLL, including Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor venetoclax, and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.

BTK inhibitors

Given the additive benefit of rituximab to chemotherapy in CLL, it was quickly extrapolated that the addition of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to a small-molecule inhibitor may improve depth and durability of response. Several phase 3 trials have shown this to be true, demonstrating superiority of the BTK inhibitor plus anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody combination over chemoimmunotherapy (Table 1). The ECOG 1912 study compared ibrutinib- rituximab to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) in patients ≤70 years old (n = 529).1 This cooperative group trial noted a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with the dual-targeted regimen; the 5-year PFS rate was 78% with ibrutinib-rituximab and 51% with FCR (P < .0001). An improvement in PFS was seen regardless of IGHV mutational status. There was also a modest overall survival (OS) benefit with ibrutinib-rituximab: 95% at 5 years compared to 89% (P = .018). The NCRI FLAIR study had a similar trial design in patients ≤75 years old (n = 771).2 The PFS was significantly longer with ibrutinib-rituximab compared to FCR (P < .001), but at a median follow-up of 53 months, there was no difference in OS.

Phase 3 trials comparing novel agents to chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naive CLL

| Reference . | Study name . | Regimen . | Eligibility . | n . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanafelt et al1 | ECOG 1912 | Ibrutinib + rituximab vs FCR | ≤70 years old without del(17p) | (n = 529) | 5-year PFS: 78% vs 51% (P < .0001) 5-year OS: 95% vs 89% (P = .018) |

| Hillmen et al2 | NCRI FLAIR | Ibrutinib + rituximab vs FCR | ≤75 years old without del(17p) | (n = 771) | Median PFS not reached vs 67 months (P < .001) No difference in OS |

| Woyach et al3 | Alliance A041202 | Ibrutinib ± rituximab vs BR | ≥65 years old | (n = 547) | Median PFS not reached with either ibrutinib arm vs 44 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Moreno et al4 | ILLUMINATE | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger coexisting conditions | (n = 229) | Median PFS not reached vs 22 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Sharman et al5 | ELEVATE TN | Acalabrutinib ± obinutuzumab vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger with comorbidities | (n = 535) | Estimated 60-month PFS: 84% (A+O), 72% (A) vs 21% (O+C) No difference in OS |

| Tam et al27 | SEQUOIA | Zanubrutinib vs BR | Without del(17p) | (n = 479) | 2-year PFS: 86% vs 70% (p < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Al-Sawaf et al7 | CLL14 | Venetoclax + obinutuzumab vs chlorambucil + obinutuzumab | CIRS >6 and/or CrCl 30-69 mL/min | (n = 432) | Median PFS not reached vs 36 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Reference . | Study name . | Regimen . | Eligibility . | n . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanafelt et al1 | ECOG 1912 | Ibrutinib + rituximab vs FCR | ≤70 years old without del(17p) | (n = 529) | 5-year PFS: 78% vs 51% (P < .0001) 5-year OS: 95% vs 89% (P = .018) |

| Hillmen et al2 | NCRI FLAIR | Ibrutinib + rituximab vs FCR | ≤75 years old without del(17p) | (n = 771) | Median PFS not reached vs 67 months (P < .001) No difference in OS |

| Woyach et al3 | Alliance A041202 | Ibrutinib ± rituximab vs BR | ≥65 years old | (n = 547) | Median PFS not reached with either ibrutinib arm vs 44 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Moreno et al4 | ILLUMINATE | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger coexisting conditions | (n = 229) | Median PFS not reached vs 22 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Sharman et al5 | ELEVATE TN | Acalabrutinib ± obinutuzumab vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger with comorbidities | (n = 535) | Estimated 60-month PFS: 84% (A+O), 72% (A) vs 21% (O+C) No difference in OS |

| Tam et al27 | SEQUOIA | Zanubrutinib vs BR | Without del(17p) | (n = 479) | 2-year PFS: 86% vs 70% (p < .0001) No difference in OS |

| Al-Sawaf et al7 | CLL14 | Venetoclax + obinutuzumab vs chlorambucil + obinutuzumab | CIRS >6 and/or CrCl 30-69 mL/min | (n = 432) | Median PFS not reached vs 36 months (P < .0001) No difference in OS |

CIRS, cumulative illness rating score; CrCl, creatinine clearance.

Alliance A041202 was a cooperative group study comparing ibrutinib with or without rituximab to bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in patients ≥65 years old (n = 547).3 There was a significantly longer PFS for both ibrutinib-containing arms compared to BR. At a median follow-up of 55 months, the median PFS was 44 months with BR but had not been reached with either ibrutinib arm (P < .0001). This benefit was seen even in higher- risk prognostic subgroups, including del(17p), del(11q), and unmutated IGHV. Interestingly, there appeared to be no significant difference in PFS between the ibrutinib monotherapy and ibrutinib-rituximab arms (P = .96). The ILLUMINATE study compared ibrutinib-obinutuzumab to chlorambucil-obinutuzumab in patients ≥65 years old or younger with coexisting conditions (n = 229).4 As expected, the targeted doublet produced a significantly longer PFS. At a median of 45 months of follow-up, the median PFS had not been reached in comparison to 22 months with the chlorambucil arm (P < .0001).

These studies highlight the efficacy and appropriateness of targeted therapy over chemoimmunotherapy, but Alliance A041202 also raises the question as to whether a dual-targeted approach is necessary when using a BTK inhibitor. The apparent lack of benefit with the addition of an anti-CD20 antibody may be attributed to the specific agents. In the ELEVATE TN study, which compared acalabrutinib (± obinutuzumab) to chlorambucil- obinutuzumab in patients ≥65 years old or younger with comorbidities, both acalabrutinib arms performed better than the chlorambucil arm (n = 535).5 However, in a post hoc analysis, the combination of obinutuzumab and acalabrutinib appeared to have a longer PFS than acalabrutinib monotherapy. At a median follow-up of 58 months, the estimated 60-month PFS rates were 84% and 72%, respectively. As the study was not powered to determine a difference between these arms, either can be considered for patients. It should be noted that the addition of obinutuzumab was associated with a greater incidence of cytopenias and grade ≥3 infections in addition to the expected infusion-related reactions.

Venetoclax + anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody

In addition to increased durability of response, it was also theorized that the addition of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to venetoclax could potentially allow for a time-limited course of therapy. The feasibility and efficacy of a fixed-duration regimen was first demonstrated in the MURANO study in relapsed/refractory patients.6 The median PFS with 2 years of venetoclax-rituximab was 54 months compared to 17 months with BR (P < .0001). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in OS: 82% vs 62% at 5 years (P < .0001). The CLL14 study subsequently evaluated a shorter course of venetoclax (1 year) with obinutuzumab in comparison to chlorambucil and obinutuzumab in treatment-naive patients (n = 432).7 At a median follow-up of 52 months, the median PFS had not been reached with venetoclax-obinutuzumab but was only 36 months with obinutuzumab-chlorambucil (P < .0001). The PFS benefit was seen in high-risk patients, including those with TP53 aberrations and unmutated IGHV. There was no difference in OS or an apparent difference in incidence in Richter's transformation. Both studies highlighted the utility of undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD) in predicting a longer PFS in patients receiving venetoclax. Furthermore, CLL14 showed that patients who completed therapy with uMRD had a longer OS, 92% at 3 years after completing therapy compared to 73% in those who had detectable minimal residual disease (MRD). Rituximab and obinutuzumab were evaluated as partners to venetoclax as part of the frontline phase 3 GAIA/CLL13 trial (n = 926).8 While these arms were not compared directly as part of the statistical design, the 15-month uMRD and 3-year PFS rates favored obinutuzumab- venetoclax (87% and 88%) over rituximab-venetoclax (57% and 81%), respectively.

Ibrutinib-venetoclax combinations

The ability to achieve uMRD has increasingly become a focus of clinical research, particularly as a tool in directing course of therapy. While the BTK inhibitors alone are typically incapable of achieving uMRD, pairing with a BCL2 inhibitor can resolve this issue (Table 2). Jain and colleagues9 were among the first to demonstrate the success of ibrutinib and venetoclax in a phase 2 frontline study. Despite most patients possessing high-risk features, 72% achieved uMRD (defined as 10−4) in the bone marrow. Patients received treatment for 24 cycles, but a trial amendment allowed for those who continued to have detectable MRD to receive an additional 12 cycles of treatment. The 4-year PFS was 95% for the entire cohort (n = 120) and an impressive 91% for those with del(17p)/TP53 mutation (n = 27).

Frontline trials of BTK-BCL2 inhibitor combinations in CLL

| Reference . | Regimen . | Eligibility (n) . | Response rate . | PFS . | MRD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jain et al9 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax | del(17p), TP53 mutation, del(11q), unmutated IGHV, or ≥65 years old (n = 120; n = 27 del(17p)/TP53 mutation) | ORR 100% (CR 88%) | 4-year PFS: 95% 4-year PFS for del(17p)/TP53 mutation: 91% | BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 56% BM-uMRD at 24 cycles: 66% |

| CAPTIVATE10-12 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax | ≤70 years old MRD cohort (n = 164) FD cohort (n = 159) | MRD cohort: ORR 97% (CR 46%) FD cohort: ORR 96% (CR 55%) | MRD cohort: Estimated 30-month PFS for all randomized cohorts: ≥95% FD cohort: 3-year PFS: 88% | MRD cohort: BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 68% FD cohort: BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 60% |

| Kater et al13 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger with CIRS >6 or CrCl <70 mL/min, without del(17p) or TP53 mutation (n = 211) | ORR 87% (CR 39%) vs 85% (CR 11%) | Estimated 3.5-year PFS: 75% vs 25% | BM-uMRD at 3 months after end of treatment: 52% vs 17% |

| Eichhorst et al8 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | CIRS ≤6, normal CrCl, without del(17p) or TP53 mutation (n = 230) | ORR 94% (CR 62%) | 3-year PFS: 91% | PB-uMRD 15 months: 92% |

| Rogers et al28 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | Excluded patients with known BTK cysteine 481 mutation (n = 50) | End of therapy ORR 90% | Estimated 48-month PFS: 96% | BM-uMRD at end of treatment: 67% |

| Ryan et al19 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | ≥18 years old No stipulation based on comorbidities or prognostic markers (n = 56; n = 29 TP53 aberrant) | ORR 98% (CR 48%) ORR TP53 aberrant: 100% (CR 52%) | NA | BM-uMRD by cycle 16: 86% BM-uMRD by cycle 16 for TP53 aberrant: 83% |

| Woyach et al29 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | ≥18 years old Intermediate- or high-risk CLL (n = 9) | ORR 100% (CR/CRi 50%) | Estimated 18-mo PFS: 100% | PB-uMRD at cycle 10: 75% |

| Tedeschi et al18 | Zanubrutinib + venetoclax | del(17p) (n = 36) | ORR 97% (CR/CRi 14%) | NA | NA |

| Soumerai et al20 | Zanubrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | del(17p) (n = 37) | ORR 100% (CR 57%) | Median PFS not reached at 30 months | BM-uMRD by cycle 17: 89% |

| Reference . | Regimen . | Eligibility (n) . | Response rate . | PFS . | MRD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jain et al9 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax | del(17p), TP53 mutation, del(11q), unmutated IGHV, or ≥65 years old (n = 120; n = 27 del(17p)/TP53 mutation) | ORR 100% (CR 88%) | 4-year PFS: 95% 4-year PFS for del(17p)/TP53 mutation: 91% | BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 56% BM-uMRD at 24 cycles: 66% |

| CAPTIVATE10-12 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax | ≤70 years old MRD cohort (n = 164) FD cohort (n = 159) | MRD cohort: ORR 97% (CR 46%) FD cohort: ORR 96% (CR 55%) | MRD cohort: Estimated 30-month PFS for all randomized cohorts: ≥95% FD cohort: 3-year PFS: 88% | MRD cohort: BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 68% FD cohort: BM-uMRD at 12 cycles: 60% |

| Kater et al13 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + chlorambucil | ≥65 years old or younger with CIRS >6 or CrCl <70 mL/min, without del(17p) or TP53 mutation (n = 211) | ORR 87% (CR 39%) vs 85% (CR 11%) | Estimated 3.5-year PFS: 75% vs 25% | BM-uMRD at 3 months after end of treatment: 52% vs 17% |

| Eichhorst et al8 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | CIRS ≤6, normal CrCl, without del(17p) or TP53 mutation (n = 230) | ORR 94% (CR 62%) | 3-year PFS: 91% | PB-uMRD 15 months: 92% |

| Rogers et al28 | Ibrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | Excluded patients with known BTK cysteine 481 mutation (n = 50) | End of therapy ORR 90% | Estimated 48-month PFS: 96% | BM-uMRD at end of treatment: 67% |

| Ryan et al19 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | ≥18 years old No stipulation based on comorbidities or prognostic markers (n = 56; n = 29 TP53 aberrant) | ORR 98% (CR 48%) ORR TP53 aberrant: 100% (CR 52%) | NA | BM-uMRD by cycle 16: 86% BM-uMRD by cycle 16 for TP53 aberrant: 83% |

| Woyach et al29 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | ≥18 years old Intermediate- or high-risk CLL (n = 9) | ORR 100% (CR/CRi 50%) | Estimated 18-mo PFS: 100% | PB-uMRD at cycle 10: 75% |

| Tedeschi et al18 | Zanubrutinib + venetoclax | del(17p) (n = 36) | ORR 97% (CR/CRi 14%) | NA | NA |

| Soumerai et al20 | Zanubrutinib + venetoclax + obinutuzumab | del(17p) (n = 37) | ORR 100% (CR 57%) | Median PFS not reached at 30 months | BM-uMRD by cycle 17: 89% |

CRi, complete response with incomplete count recovery; FD, fixed duration.

The phase 2 CAPTIVATE study also evaluated the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax with duration of therapy determined by an MRD-guided approach in previously untreated patients ≤70 years old. The trial design consisted of 2 cohorts: an MRD-driven cohort and a separate fixed-duration cohort. After 3 cycles of ibrutinib lead-in, patients received ibrutinib and venetoclax for 12 cycles. In the MRD cohort (n = 164), the best uMRD response rates were 75% (peripheral blood) and 68% (bone marrow).10 Patients were subsequently randomized. Those with uMRD were randomized to receive a placebo (n = 43) or ibrutinib (n = 43), whereas those who did not have confirmed uMRD received ibrutinib (n = 31) or ibrutinib plus venetoclax (n = 32). For those with uMRD, the estimated 30-month PFS was 95% with placebo and 100% with ibrutinib. For those who did not have confirmed uMRD, the estimated 30-month PFS rate was 95% with ibrutinib and 97% with ibrutinib-venetoclax. In the subsequent fixed- duration cohort, therapy consisted solely of 3 cycles of ibrutinib lead-in, followed by 12 cycles of the combination (n = 159).11 The overall response rate (ORR) was 96% with a complete response (CR) of 55%. uMRD rates in the peripheral blood and bone marrow were 77% and 60%, respectively. At 36 months, PFS was 88%.12 Given these impressive results with the fixed-duration cohort, it is unclear whether an MRD-guided approach is truly warranted in this setting and more follow-up is necessary.

Given these exciting findings, the GLOW study sought to compare the ibrutinib-venetoclax regimen to obinutuzumab- chlorambucil in patients ≥65 years old or younger with comorbidities who did not have del(17p) or TP53 mutation.13 The duration of ibrutinib-venetoclax was 12 cycles. While the ORRs were similar between the arms, the ibrutinib-venetoclax combination produced a significantly longer PFS (P < .001), regardless of age or comorbidities. Neutropenia was the most common grade ≥3 adverse event noted, occurring in 35% of patients receiving the biologic doublet and 50% of those receiving chemoimmunotherapy; grade ≥3 infection was seen in 17% and 12% of patients, respectively. Tumor lysis syndrome did not occur in the ibrutinib-venetoclax arm but did occur in 6% of patients receiving obinutuzumab-chlorambucil. There was no difference in OS between the arms.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient has a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and would like to avoid ibrutinib. He is extremely interested in an oral regimen with a fixed duration, however, and inquires as to whether there are other options. You inform him that the BTK-BCL2 inhibitor combination has not yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for CLL, but there are data to support the use of other BTK inhibitors in combination with venetoclax.

Second-generation BTK inhibitor combinations with venetoclax

Toxicity is the most common reason for discontinuation of ibrutinib in the frontline setting.14 The second-generation BTK inhibitors, acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, have shown improved safety profiles when compared directly to ibrutinib in relapsed/ refractory CLL.15,16 Additionally, it has become increasingly evident that ibrutinib is associated with a significant risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death.17 As such, there is considerable interest in second-generation BTK inhibitor combinations with venetoclax.

Arm D of the SEQUOIA study evaluated the combination of zanubrutinib and venetoclax in treatment-naive patients with del(17p).18 Efficacy data available from 36 patients indicated an ORR of 97% and CR/CR of 14%. Longer follow-up is needed, but the regimen appears well tolerated. Davids and colleagues19 expanded on this concept by designing a multitargeted regimen of acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab for treatment-naive patients. After a staggered initiation of each agent, patients were eligible to discontinue therapy after cycle 15 if in a CR with uMRD or after cycle 24 if with uMRD in a partial response. Of the 56 patients evaluable, the ORR was 98%, and 86% had uMRD in the bone marrow by cycle 16. In a similar frontline study of zanubrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab, the ORR was 100% (CR 57%) among the 37 evaluable patients. Eighty-nine percent of patients had achieved uMRD and were able to discontinue therapy after a median of 10 cycles.20

Whether a triplet regimen is necessary with these highly active targeted agents remains a question. The previously mentioned GAIA/CLL13 trial suggests that there might not be a need based on the results of a third arm consisting of obinutuzumab, venetoclax, and ibrutinib. The 15-month uMRD and 3-year PFS rates were similar to the obinutuzumab-venetoclax arms: 92% and 91% with the triplet and 87% and 88% with the doublet.8 Several ongoing phase 3 studies are formally comparing triplet to doublet regimens (Table 3). These all-oral doublet regimens are impressive, and they challenge even the newer standard of obinutuzumab-venetoclax. The ongoing MAJIC study of obinutuzumab-venetoclax vs a fixed duration of acalabrutinib and venetoclax will help answer that question. The CLL17 study of obinutuzumab-venetoclax vs a fixed duration of ibrutinib-venetoclax vs ibrutinib monotherapy will also address this matter as well as compare the efficacy of continuous BTK inhibition.

Ongoing phase 3 trials of BTK-BCL2 inhibitor combinations in treatment-naive CLL

| Study name . | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier . | Regimen . | Eligibility . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLL16 (German CLL Study Group) | NCT05197192 | Acalabrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax | High risk with either del(17p), TP53 mutation, or complex karyotype |

| A041702 (Alliance) | NCT03737981 | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs ibrutinib + obinutuzumab | ≥65 years old |

| EA9161 (ECOG-ACRIN) | NCT03701282 | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs ibrutinib + obinutuzumab | < 70 years old without del(17p) |

| MAJIC | NCT05057494 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax | ≥18 years old No stipulation prognostic markers |

| CLL-17 (German CLL Study Group) | NCT04608318 | Continuous ibrutinib vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs fixed-duration ibrutinib + venetoclax | ≥18 years old No stipulation prognostic markers |

| Study name . | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier . | Regimen . | Eligibility . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLL16 (German CLL Study Group) | NCT05197192 | Acalabrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax | High risk with either del(17p), TP53 mutation, or complex karyotype |

| A041702 (Alliance) | NCT03737981 | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs ibrutinib + obinutuzumab | ≥65 years old |

| EA9161 (ECOG-ACRIN) | NCT03701282 | Ibrutinib + obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs ibrutinib + obinutuzumab | < 70 years old without del(17p) |

| MAJIC | NCT05057494 | Acalabrutinib + venetoclax vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax | ≥18 years old No stipulation prognostic markers |

| CLL-17 (German CLL Study Group) | NCT04608318 | Continuous ibrutinib vs obinutuzumab + venetoclax vs fixed-duration ibrutinib + venetoclax | ≥18 years old No stipulation prognostic markers |

How I treat frontline CLL in 2023

Chemoimmunotherapy is no longer considered appropriate for most patients with CLL. With the plethora of novel agents now approved, oncologists have several effective options to choose from for frontline treatment. A myriad of factors should be taken into consideration, including prognostic factors, comorbidities, feasibility of administration, financial cost, and patient preference. The first decision point is whether to use a single-agent BTK inhibitor or the obinutuzumab-venetoclax combination. One of the most important details in making this decision is the presence or absence of del(17p)/TP53 aberration.

Although venetoclax was initially approved in relapsed/ refractory patients with del(17p), there are limited data with obinutuzumab-venetoclax in frontline patients. It appears that a fixed duration of venetoclax cannot completely overcome the inferior prognosis associated with TP53 aberrancy. In the CLL14 study, the 4-year PFS for patients with TP53 mutation/ deletion (n = 25) was only 53% compared to 77% in those without (n = 184).7 In contrast, the prolonged use of a BTK inhibitor appears to be more beneficial in this population. In a pooled analysis of 89 patients with TP53 aberrations receiving ibrutinib in the frontline setting, the estimated 4-year PFS was 79%, and the median PFS had not been reached at a median follow-up of 50 months.21 The ELEVATE-TN and SEQUOIA studies showed similar efficacy with acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib in this high-risk population; the 5-year PFS in both acalabrutinib arms was 71% and the 42-month PFS with zanubrutinib was 79%.5,22

Medical comorbidities such as cardiac history, bleeding tendencies, and renal dysfunction are also important in determining appropriate therapy. As previously discussed, ibrutinib is associated with significant cardiac complications. There is a suggestion that this might be true with acalabrutinib, but more data are needed.23 All of the approved covalently binding BTK inhibitors are associated with increased bruising, which is less attractive for patients in whom there are concerns about bleeding complications. In contrast, venetoclax requires hospitalization and rigorous monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) in patients with a decreased creatinine clearance. Both classes of drugs decrease the efficacy of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, which is of particular concern in this vulnerable population.24 A fixed-duration regimen may be attractive as there appears to be some immune reconstitution after drug discontinuation that allows for a serologic response.25

Patient preference and feasibility of administration should also be considered. BTK inhibitors are self-administered and require relatively few clinic visits but are prescribed indefinitely and are associated with ongoing risk of adverse events. Obinutuzumab- venetoclax requires a cumbersome initial start, including frequent infusion visits and laboratory monitoring, but allow for a limited duration of therapy as well as a shorter interval for drug and financial toxicity. Furthermore, it appears that patients can be effectively retreated with venetoclax.26

The treatment algorithm for CLL will continue to evolve in coming years as we learn more about the BTK-BCL2 inhibitor combinations, including the populations they most benefit, the role for MRD, and how best to sequence these agents. For now, the BTK-BCL2 inhibitor combinations, with or without anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, remain investigational.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient completes the remainder of workup for CLL. Laboratory testing indicates a decreased creatinine clearance of 70 mL/min and mildly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 283. Computed tomography imaging indicates abdominal nodes of up to 6 cm. After thorough discussion with you, the patient elects to receive venetoclax and obinutuzumab. He lives close to your clinic/hospital and is comfortable with laboratory monitoring schedule required for the venetoclax dose ramp-up. Peripheral blood flow cytometry indicates uMRD at the end of the fixed duration of venetoclax.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Chaitra Ujjani: consultancy for Abbvie, Astrazeneca, Pharmacyclics, Janssen, Genentech, Beigene, and Eli Lilly; research funding from Abbvie, Astrazeneca, Pharmacyclics, and Eli Lilly.

Off-label drug use

Chaitra Ujjani: This article includes discussion of off-label drug use.