Abstract

The current mainstay of therapy for hemophilia is to replace the deficient clotting factor with the intravenous administration of exogenous clotting factor concentrates. Prophylaxis factor replacement therapy is now considered the standard of care in both pediatric and adult patients with hemophilia with a severe phenotype to protect musculoskeletal health and improve quality of life. Heterogeneity in bleeding presentation among patients with hemophilia due to genetic, environmental, and treatment-related factors has been well described. Accordingly, the World Federation of Hemophilia recommends an individualized prophylaxis regimen that considers the factors mentioned above to meet the clinical needs of the patient, which can vary over time. This review focuses on the practical points of choosing the type of factor concentrate, dose, and interval while evaluating appropriate target trough factor levels and bleeding triggers such as level of physical activity and joint status. We also discuss the use of a pharmacokinetics assessment and its incorporation in the clinic for a tailored approach toward individualized management. Overall, adopting an individualized prophylaxis regimen leads to an optimal utilization of factor concentrates with maximum efficacy and minimum waste.

Learning Objectives

Describe the different environmental and treatment-related variables involved in determining an appropriate prophylaxis regimen

Understand the importance of an individualized prophylaxis regimen that meets the clinical needs of hemophilia patients

CLINICAL CASE

A 15-year-old adolescent boy with moderate hemophilia A (HA; baseline factor VIII 2%) presented to a hematology clinic to discuss whether he should start prophylaxis with clotting factor concentrates (CFCs). He was diagnosed at the age of 3 by his astute pediatrician when he developed severe right knee hemarthrosis after tripping while running. Throughout his childhood and adolescent years, he required infrequent on-demand administration of CFCs predominantly due to trauma-induced acute knee hemarthrosis from playing softball and basketball. He recalled 3 episodes of spontaneous knee hemarthrosis occurring about once per year in the last 3 years. He was now in high school and wanted to play basketball competitively, with 3 practice games per week and more during tournament season. He was concerned about his increased risk of bleeding given his history of spontaneous joint bleeds and the high likelihood of musculoskeletal injuries, such as sprained ankles and knee ligament tears, that can occur while playing basketball.

Introduction

HA and hemophilia B (HB) are X-linked bleeding disorders that result from decreased or deficient plasma clotting factors VIII (FVIII) and IX (FIX), respectively. The severity of hemophilia has traditionally been defined based on the degree of the clotting factor deficiency, with levels of >5% to 40% classified as mild hemophilia, 1% to 5% as moderate, and <1% as severe.1 The severity and frequency of bleeding in hemophilia typically correlate with the degree of the clotting factor deficiency (Table 1).

Association of bleeding manifestations with severity of disease based on plasma clotting factor levels

| Severity . | Plasma clotting factor levels . | Bleeding manifestations . |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 5%-<40% of normal | Bleeding with major trauma or surgery; rare spontaneous bleeding |

| Moderate | 1%-5% of normal | Bleeding with minor trauma or surgery; occasional spontaneous bleeding |

| Severe | <1% of normal | Spontaneous bleeding predominantly in the joints or muscles but can occur anywhere, including life-threatening intracranial bleed |

| Severity . | Plasma clotting factor levels . | Bleeding manifestations . |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 5%-<40% of normal | Bleeding with major trauma or surgery; rare spontaneous bleeding |

| Moderate | 1%-5% of normal | Bleeding with minor trauma or surgery; occasional spontaneous bleeding |

| Severe | <1% of normal | Spontaneous bleeding predominantly in the joints or muscles but can occur anywhere, including life-threatening intracranial bleed |

Adapted with permission from Srivastava, A, Santagostino, E, Dougall, A, et al. WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition.9 © 2020 World Federation of Hemophilia. Haemophilia © 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

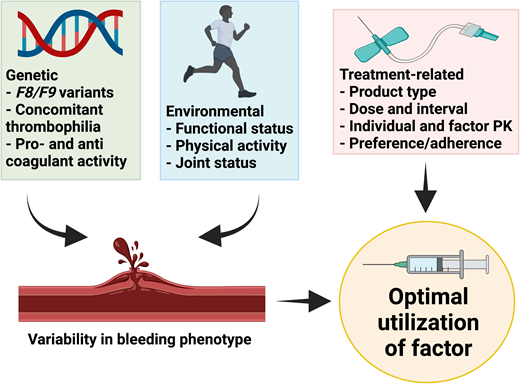

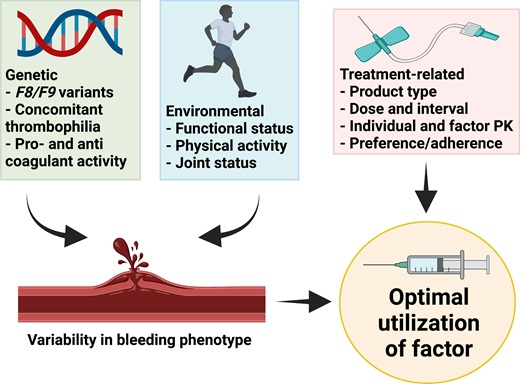

The mainstay of therapy for hemophilia is to replace the deficient clotting factor, usually by intravenous administration of exogenous CFC. This can be episodic to treat bleeding events or on a regular basis (prophylaxis) to prevent bleeding episodes.1 Heterogeneity in bleeding presentation between patients with similar severity of disease or between patients with HA and HB is well recognized.2-4 Similarly, patients with moderate hemophilia can present phenotypically as those with severe disease.5 The basis for this phenotypic variation is multifactorial and includes (1) genetic factors such as the F8/F9 genotype (null vs nonnull variants),6 concomitant thrombophilic gene variants or other bleeding disorders,7 and intrinsic pro- and anticoagulant activity,6 and (2) environmental factors that can vary for an individual over time, such as functional status, levels and patterns of physical activity, and joint status.8 Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, the optimal utilization of CFC takes into account both genetic and environmental factors as well as treatment-related factors such as factor type and dose, individual and product pharmacokinetics (PK) of factor, and individual preference and adherence (Figure 1).

Factors that lead to optimal utilization of CFC. Created with BioRender.com.

In this review, we focus on prophylaxis factor replacement therapy and practical points around choosing the type of concentrate, dose, and interval while considering trough factor levels and bleeding triggers. Finally, we briefly discuss the use of PK assessment for individualized management and its incorporation in the clinic. The use of CFC in the management of hemophilia patients with inhibitors and the optimal utilization of factor replacement therapy during surgery are beyond the scope of this paper. Readers are directed to the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines on the dosage and duration of CFC coverage for major and minor surgeries (Srivastava et al; Table 7-2).9 During the perioperative period, both standard half-life (SHL) and extended half-life (EHL) CFC can be given via continuous infusion or intermittent bolus.10-12

Prophylaxis as the standard of care

Since completion of the Joint Outcome Study,13 and ESPRIT14 study for children with severe HA, and the SPINART study15 for adolescents and adults with severe HA, the use of prophylaxis factor replacement therapy is now considered the standard of care. The recently updated WFH guidelines recommend that pediatric and adult patients with hemophilia with a severe phenotype (to include those with moderate hemophilia with a severe phenotype) be on prophylaxis to prevent spontaneous and breakthrough bleeding at all times.9 Specifically for children, the WFH guidelines recommend the early initiation of prophylaxis ideally before age 3, as this has been shown to have better long-term joint outcomes compared to starting after age 6.9,16,17

Types of factor concentrates

For a rare disorder, the armamentarium of CFCs available is noteworthy, with a wide range of products in use around the world. The 2 main types of SHL CFC are the virally inactivated plasma-derived lyophilized factor concentrates and the recombinant factor concentrates manufactured from genetically engineered cells; both have high clinical efficacy and safety.18 Table 2 lists the CFCs currently licensed for use in the United States. An updated list of all currently available products globally and their manufacturing details are available in the WFH Online Registry of Clotting Factor Concentrates.19

CFCs licensed in the US to treat HA and HB

| Brand (nonproprietary name) . | Technology . | Manufacturer-recommended starting dose for prophylaxis use* . |

|---|---|---|

| Factor VIII products | ||

| Kogenate FS® (octocog alfa) | Second generation: full-length recombinant | Adults: 25 IU/kg 3 times weekly; children: 25 IU/kg every other day |

| Advate® (octocog alfa) | Third generation: full-length recombinant | 20-40 IU/kg every other day |

| Kovaltry® (octocog alfa) | Third generation: full-length recombinant | Adults/adolescents: 20-40 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly; children ≤12 years: 25-50 IU/kg 2 times weekly, 3 times weekly, or every other day |

| NovoEight® (turoctocog alfa) | Third generation: B-domain truncated | Adults/adolescents: 20-50 IU/kg 3 times weekly or 20-40 IU/kg every other day; children <12 years: 25-60 IU/kg 3 times weekly or 25-50 IU/kg every other day |

| Xyntha®/ReFacto AF® (moroctocog alfa) | Third generation: B-domain deleted | Adults/adolescents: 30 IU/kg 3 times weekly; children <12 years: 25 IU/kg every other day |

| Nuwiq® (simoctocog alfa) | Fourth generation: B-domain deleted | Adults/adolescents: 30-40 IU/kg every other day; children <12 years: 30-50 IU/kg every other day or 3 times weekly |

| Hemofil M® | Plasma-derived immunoaffinity-purified FVIII | Not provided |

| Koate® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Humate-P® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Alphanate® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Factor IX products | ||

| BeneFIX® (nonacog alfa)† | Recombinant FIX | Age ≥16 years: 100 IU/kg weekly |

| Ixinity® (trenonacog alfa)‡ | Recombinant FIX | Adults: 40-70 IU/kg twice weekly |

| Rixubis® (nonacog gamma) | Recombinant FIX | Age ≥12 years: 40-60 IU/kg twice weekly; children <12 years: 60-80 IU/kg twice weekly |

| Alphanine | Plasma derived | Not provided |

| Brand (nonproprietary name) . | Technology . | Manufacturer-recommended starting dose for prophylaxis use* . |

|---|---|---|

| Factor VIII products | ||

| Kogenate FS® (octocog alfa) | Second generation: full-length recombinant | Adults: 25 IU/kg 3 times weekly; children: 25 IU/kg every other day |

| Advate® (octocog alfa) | Third generation: full-length recombinant | 20-40 IU/kg every other day |

| Kovaltry® (octocog alfa) | Third generation: full-length recombinant | Adults/adolescents: 20-40 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly; children ≤12 years: 25-50 IU/kg 2 times weekly, 3 times weekly, or every other day |

| NovoEight® (turoctocog alfa) | Third generation: B-domain truncated | Adults/adolescents: 20-50 IU/kg 3 times weekly or 20-40 IU/kg every other day; children <12 years: 25-60 IU/kg 3 times weekly or 25-50 IU/kg every other day |

| Xyntha®/ReFacto AF® (moroctocog alfa) | Third generation: B-domain deleted | Adults/adolescents: 30 IU/kg 3 times weekly; children <12 years: 25 IU/kg every other day |

| Nuwiq® (simoctocog alfa) | Fourth generation: B-domain deleted | Adults/adolescents: 30-40 IU/kg every other day; children <12 years: 30-50 IU/kg every other day or 3 times weekly |

| Hemofil M® | Plasma-derived immunoaffinity-purified FVIII | Not provided |

| Koate® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Humate-P® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Alphanate® | Plasma-derived containing FVIII and von Willebrand factor | Not provided |

| Factor IX products | ||

| BeneFIX® (nonacog alfa)† | Recombinant FIX | Age ≥16 years: 100 IU/kg weekly |

| Ixinity® (trenonacog alfa)‡ | Recombinant FIX | Adults: 40-70 IU/kg twice weekly |

| Rixubis® (nonacog gamma) | Recombinant FIX | Age ≥12 years: 40-60 IU/kg twice weekly; children <12 years: 60-80 IU/kg twice weekly |

| Alphanine | Plasma derived | Not provided |

Recommended doses based on US package insert.

In the US, BeneFIX® is approved for prophylaxis use in those aged ≥16 years only, whereas in the EU it is approved for prophylaxis use at all ages.

In the US, Ixinity® is approved for prophylaxis use in adults only. It is not approved in the EU.

For HA patients, there is a clinical concern that recombinant FVIII concentrates may contribute to a higher rate of inhibitor development in previously untreated patients (PUPs) compared to plasma-derived FVIII concentrates, although this remains highly controversial.20,21 Conversely, the risk of inhibitor development in HB patients is not thought to be related to the type of CFC.9 Inhibitors are immunoglobulin G (IgG) alloantibodies to exogenous FVIII or FIX that neutralize the function of infused CFC and mostly occur within the first 50 exposures.1,22 An exposure is defined as any infusion of a FVIII/FIX-containing product in a 24-hour period.1 Meta-analyses of observational studies, including patient-level data, found no differences in inhibitor rates when comparing all plasma-derived FVIII concentrates to all recombinant FVIII concentrates.20,23,24 In contrast, the much-awaited Survey of Inhibitors in Plasma-Product Exposed Toddlers (SIPPET) study, the only prospective, randomized controlled trial, found that PUPs treated with recombinant FVIII products had a higher cumulative incidence of inhibitors (44.5%; 95% CI, 34.7-54.3) compared with those treated with plasma-derived FVIII products (26.8%; 95% CI, 18.4-35.2).21 The generalizability and applicability of SIPPET have been widely debated in numerous conferences and review articles and is beyond the scope of this review. The interested reader is directed to the National Hemophilia Foundation's Medical and Scientific Advisory Council document 243 for a detailed explanation of the differences between SIPPET and prior observational studies and their recommendations.25 Additionally, the European Medicines Agency Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee concluded in 2017 that no clear evidence exists of inhibitor risk differences between plasma-derived and recombinant factor VIII concentrates.26 Ongoing research through the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network 8 PUPs Matter study, a longitudinal observational study collecting treatment and inhibitor data on children with moderate and severe HA or HB born on or after 1 January 2010, may help provide additional clarity on this issue.27 At this time, the WFH does not express a preference for product type and recommends product selection based on local availability, cost, and provider/patient preference.9

For previously treated patients, classically defined as having received >150 exposure (although others have considered it to be >50 exposure),28 the risk of inhibitor development is low.22 Additionally, studies indicate no increased risk of inhibitor development when switching to another type or brand of factor.29,30 Whether to use plasma-derived vs recombinant factor concentrates is a matter of dealer's choice. Practically, regional availability and payers (government or insurance companies) preference due to negotiated procurement discounts (as well as out-of-pocket cost for US patients) play a larger role in determining the specific product of CFC to prescribe within each type.

Dose and interval

The dose and interval of a prophylaxis regimen depend on the half-life of the CFC—the time for factor concentration to reach half of its original peak concentration. In adults, the half-life can range between 8 and 12 hours for FVIII concentrates and 18 and 30 hours for FIX concentrates, depending on the brand of factor; in children the half-life is shorter.31,32 Although most manufacturers provide recommended starting doses for prophylaxis (Table 2), multiple regimens exist and vary widely. These regimens range from a high-dose approach that involves the administration of 25 to 40 IU/kg per dose every other day (for SHL FVIII concentrates) or twice per week (for SHL FIX concentrates) to a low-dose approach that involves once-weekly or twice-weekly infusion and/or using lower doses to a regimen in between these 2 approaches. The low-dose approach is predominantly used in resource-constrained countries where access to CFCs is limited. The benefits of such an approach over episodic treatment have been demonstrated without incurring a huge financial burden.33 Thus, depending on local resources and economic constraints, a starting regimen of one of the aforementioned approaches is selected that is mutually acceptable to both clinician and patient/caregiver and then tailored (escalated or de-escalated) to the patient's clinical needs.

Target trough levels

Historically, the goal of prophylaxis replacement therapy has been to target a trough factor level of at least 1% (ie, converting a patient with severe hemophilia to the typical bleeding phenotype of moderate hemophilia) to prevent spontaneous joint bleed and to reduce damage to musculoskeletal health.9,31,34 However, given the aforementioned phenotypic variations observed, the traditional target trough level of 1% does not prevent bleeding in all hemophilia patients.35 Also, for patients with moderate hemophilia with frequent spontaneous bleeding (a severe phenotype), a target trough level of 1% is clinically unhelpful.36

So what should the target trough level be to achieve zero bleeds for all and is this attainable? Studies in mild and moderate hemophilia patients observed that the annual number of joint bleeds decreases as baseline factor activity increases and approaches zero with a baseline factor activity of >15% to 30%.4,37 Predictive modeling studies in severe HA patients on prophylaxis factor replacement therapy projected that every 1% rise in trough FVIII levels resulted in a 2% increase in the number of patients who might achieve zero bleeds in a year.38 Accordingly, most clinicians favor targeting a higher trough level (>3%-5% or higher) but are prohibited from doing so due to the constraints of SHL CFCs that require almost daily infusions to achieve this level. In addition to the burden of daily dosing, this strategy is also cost-prohibitive.

Bleeding triggers

The level and pattern of physical activity as well as underlying musculoskeletal health can act as bleeding triggers, contributing to the bleeding phenotype. School-aged children and college students often engage in sports and should be encouraged to do so, even if some restrictions or modifications are necessary.39 Several retrospective studies concluded that participation in organized sports (including high-risk sports such as basketball and football) by children and adolescents with severe hemophilia on prophylaxis factor replacement therapy was not associated with increased bleeding complications.40,41 However, depending on the activity, a change in the prophylaxis dose and/or schedule or an additional preactivity factor infusion may be indicated. Even though it is widely agreed that higher factor levels are required with higher-risk physical activities, clinical data on what constitutes a protective factor level to safely participate in high-risk activities are lacking. A Delphi consensus statement suggested a factor level of 3% to 5% for mild physical activity and 5% to 15% for higher-risk physical activity,42 whereas a more recent expert solicitation exercise suggested much higher levels of up to 40% to 50% (Table 3).43 Regardless of factor levels, additional strategies including proper coaching and supervision, appropriate use of safety equipment, and suitable footwear are equally important to maximize safety for these patients.44 To ensure safe participation, a well-informed discussion among the health care provider, patient, parents, and coaches should take place. The National Hemophilia Foundation's Playing It Safe guide may be helpful in these discussions, as it categorizes the level of risk and provides information on safety measures for >80 sporting activities.39

Estimates of minimum factor levels corresponding to National Hemophilia Foundation categories of risks for physical activities

| Risk level . | Examples of physical activities* . | Minimum factor levels (Mean ± SD)† . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without joint morbidity . | With joint morbidity‡ . | ||

| 1 – low | Aquatics, archery, elliptical machine, frisbee, golf, hiking, tai chi, snorkeling, stationary bike, stepper, swimming, walking | 4 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| 1.5 – low-moderate | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, body-sculpting class, canoeing, cheerleading, circuit training, dance, fishing, frisbee, hiking, horseback riding, indoor-cycling class, kayaking, Pilates, indoor rock climbing, rowing, rowing machine, nonmotorized scooter, skateboarding, ice skating, inline skating, ski machine, softball, stepper, strength training, T-ball, treadmill, yoga, Zumba class | 7 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 |

| 2 – moderate | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, boot camp workout class, bowling, canoeing, cardio kickboxing class, cheerleading, dance, diving, fishing, touch football, gymnastics, CrossFit, horseback riding, indoor-cycling class, Jet Ski, jumping rope, kayaking, martial arts, Pilates, river rafting, rock climbing, running/jogging, motorized and nonmotorized scooters, scuba diving, skateboarding, ice skating, cross-country skiing, water skiing, soccer, softball, surfing, tennis, track and field, volleyball, yoga, Zumba class | 11 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 |

| 2.5 – moderate-high | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, bounce houses, canoeing, cheerleading, dance, diving, gymnastics, CrossFit, hockey, horseback riding, Jet Ski, kayaking, martial arts, mountain biking, racquetball, outdoor rock climbing, motorized and nonmotorized scooter, scuba diving, skateboarding, ice skating, downhill skiing, water skiing, snowboarding, soccer, softball, surfing, track and field, trampoline, volleyball, water polo | 19 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 |

| 3 – high | Bicycling, BMX racing, bounce houses, boxing, dance, diving, tackle football, gymnastics, CrossFit, hockey, Jet Ski, lacrosse, martial arts, dirt bikes, powerlifting, outdoor rock climbing, rodeo, rugby, snowmobiling, soccer, trampoline, wrestling | 38 ± 2 | 47 ± 2 |

| Risk level . | Examples of physical activities* . | Minimum factor levels (Mean ± SD)† . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without joint morbidity . | With joint morbidity‡ . | ||

| 1 – low | Aquatics, archery, elliptical machine, frisbee, golf, hiking, tai chi, snorkeling, stationary bike, stepper, swimming, walking | 4 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| 1.5 – low-moderate | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, body-sculpting class, canoeing, cheerleading, circuit training, dance, fishing, frisbee, hiking, horseback riding, indoor-cycling class, kayaking, Pilates, indoor rock climbing, rowing, rowing machine, nonmotorized scooter, skateboarding, ice skating, inline skating, ski machine, softball, stepper, strength training, T-ball, treadmill, yoga, Zumba class | 7 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 |

| 2 – moderate | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, boot camp workout class, bowling, canoeing, cardio kickboxing class, cheerleading, dance, diving, fishing, touch football, gymnastics, CrossFit, horseback riding, indoor-cycling class, Jet Ski, jumping rope, kayaking, martial arts, Pilates, river rafting, rock climbing, running/jogging, motorized and nonmotorized scooters, scuba diving, skateboarding, ice skating, cross-country skiing, water skiing, soccer, softball, surfing, tennis, track and field, volleyball, yoga, Zumba class | 11 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 |

| 2.5 – moderate-high | Baseball, basketball, bicycling, bounce houses, canoeing, cheerleading, dance, diving, gymnastics, CrossFit, hockey, horseback riding, Jet Ski, kayaking, martial arts, mountain biking, racquetball, outdoor rock climbing, motorized and nonmotorized scooter, scuba diving, skateboarding, ice skating, downhill skiing, water skiing, snowboarding, soccer, softball, surfing, track and field, trampoline, volleyball, water polo | 19 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 |

| 3 – high | Bicycling, BMX racing, bounce houses, boxing, dance, diving, tackle football, gymnastics, CrossFit, hockey, Jet Ski, lacrosse, martial arts, dirt bikes, powerlifting, outdoor rock climbing, rodeo, rugby, snowmobiling, soccer, trampoline, wrestling | 38 ± 2 | 47 ± 2 |

Examples of physical activities based on National Hemophilia Foundation categories of risk. Depending on the intensity of the physical activity, some activities are in multiple risk-level categories.39

Minimum factor levels for participation in physical activities based on an expert elicitation exercise.43

Joint morbidity was defined as having one or more “damaged joints”—ie, any joint permanently damaged as a result of the patient's bleeding disorder or associated with chronic joint pain and/or limited range of movement due to compromised joint integrity.43

Hemophilia patients who have underlying joint damage (target joints) from prior bleeds at a young age usually require higher factor trough levels and hence higher factor use to prevent future bleeds. The age at first joint bleed is an early indicator of the patient's bleeding phenotype.2 Patients who experience their first joint bleed earlier in life tend to have higher annual CFC utilization and to develop more arthropathy in later years than patients who have their first joint bleed at a later age.2 This highlights the importance of early prophylaxis, as even a few bleeds prior to starting prophylaxis can contribute to long-term joint damage.13

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The decision was made to start the patient on prophylaxis factor replacement therapy, given his history of 3 spontaneous joint bleeds. He had received recombinant SHL FVIII CFC in the past for treatment of his acute joint bleeds and opted to continue with the same product. The product was on his insurance company's preferred drug list and was on formulary at the local hospital. He started at a dose of 25 IU/kg 3 times per week, to be infused prior to his basketball practices on Tuesday and Thursday evenings and Saturday morning, to reduce the risk of bleeding from basketball injury and to reduce spontaneous joint bleeds at all times. Occasionally, when he had additional basketball matches on Saturday evening, he would infuse 40 IU/kg on Saturday morning instead. In addition, strategies to minimize his injury risk by using eye protection, elbow pads and kneepads, mouth guards, athletic supporters, and proper footwear were discussed with the patient. He learned how to self-infuse, and his basketball coach also received infusion training.

Over the next 3 years, he continued on the same regimen and reported no injury-related bleeds from playing basketball. He noted breakthrough joint bleeds involving the right knee occurring about twice a year, which he treated using his prophylaxis 25 IU/kg dose each time. He then started college and returned to playing basketball casually. Because of this and a part-time job to support his tuition, his adherence to the prophylaxis regimen dropped. He missed a dose about once every 2 weeks due to competing demands on his time. He began to experience more breakthrough joint bleeds, particularly in his right knee, about once every month. He returned to the clinic to discuss his options.

EHL CFCs

The high treatment burden associated with prophylaxis factor replacement therapy, given the frequency of infusions using SHL CFC, often leads to a less than optimal degree of adherence. In the last decade, EHL products were engineered to reduce infusion frequency and to maintain a higher factor trough level for better protection against spontaneous bleeding. This was achieved using techniques including fusion with either albumin or the monomeric Fc fragment of immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) or conjugation with polyethylene glycol (PEG). In the first technique, the neonatal Fc receptor inhibits lysosomal degradation of fusion proteins and recycles them back into the circulation,45 whereas PEGylation delays the degradation and renal elimination of its attached clotting factor.46 A novel strategy to increase the stability and affinity of FVIII to von Willebrand factor (VWF) to reduce the risk of inhibitor development led to the development of single-chain forms of FVIII.47 This strategy resulted in the added benefit of a favorable half-life, which allows for dosing twice per week, similar to other EHL FVIII products.48 Although this strategy was not intended to extend the half-life, it is included as an EHL product for the sake of completeness. All currently available EHL CFCs have been shown to be efficacious in the prevention and treatment of bleeds with no evidence of any clinical safety issues,9,49 albeit theoretical concerns remain regarding lifelong use of PEGylated CFC.50 This has led to varying regulatory approval for some PEGylated products for prophylaxis use in the pediatric population (Table 4). When selecting an EHL CFC, the same practical measures apply—local availability, payer preference, and cost. For EHL products, an additional decision point for clinicians is the ability or availability of local assays to monitor FVIII/FIX levels accurately. Certain EHL CFCs require chromogenic factor assays or one-stage FVIII/FIX assays that have been validated for use (Table 4).51,52 Hence, the lack of appropriate FVIII/FIX assays for monitoring may also influence product selection.

Characteristics of EHL CFCs

| Brand (nonproprietary name) . | Technology . | Licensed for prophylaxis use . | Manufacturer-recommended starting dose for prophylaxis use* . | Recommended assay for monitoring . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor VIII products | ||||

| Eloctate®/Elocta® (efmoroctocog alfa) | B-domain deleted FVIII fused to Fc portion of IgG1 | US & EU: all ages | Adults: 50 IU/kg every 4 days; children <6 years: 50 IU/kg twice weekly | One stage or chromogenic |

| Adynovate®/Adynovi® (rurioctocog alfa pegol) | Full-length recombinant FVIII with 20 kDa PEG | US: all; EU: ≥12 years | Adolescents/adults: 40-50 IU/kg 2 times weekly; children <12 years: 55 IU/kg 2 times weekly | One stage or chromogenic |

| Jivi® (damoctocog alfa pegol) | B-domain deleted FVIII with 60 kDa PEG | US & EU: ≥12 years | 30–40 IU/kg twice weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Esperoct® (turoctocog alfa pegol) | B-domain truncated FVIII with 40 kDa PEG | US: all; EU: ≥12 years | Adolescents/adults: 50 IU/kg every 4 days; children <12 years: 65 IU/kg twice weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Afstyla® (lonoctocog alfa) | Single-chain recombinant FVIII | US & EU: all ages | Adults: 20-50 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly; children <12 years: 30-50 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly | Chromogenic assay |

| Factor IX products | ||||

| Alprolix® (efrenonacog alfa) | Recombinant FIX fused to Fc portion of IgG1 | US & EU: all ages | Adolescents/adults: 50 IU/kg weekly or 100 IU/kg every 10 days; children <12 years: 60 IU/kg weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Idelvion® (albutrepenonacog alfa) | Recombinant FIX fused to albumin | US & EU: all ages | Adolescents/adults: 25-40 IU/kg weekly; children <12 years: 40-55 IU/kg weekly | One stage with validated reagents† |

| Rebinyn®/Refixia® (nonacog beta pegol) | Recombinant FIX with 40 kDa PEG | EU: ≥12 years | 40 IU/kg weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Brand (nonproprietary name) . | Technology . | Licensed for prophylaxis use . | Manufacturer-recommended starting dose for prophylaxis use* . | Recommended assay for monitoring . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor VIII products | ||||

| Eloctate®/Elocta® (efmoroctocog alfa) | B-domain deleted FVIII fused to Fc portion of IgG1 | US & EU: all ages | Adults: 50 IU/kg every 4 days; children <6 years: 50 IU/kg twice weekly | One stage or chromogenic |

| Adynovate®/Adynovi® (rurioctocog alfa pegol) | Full-length recombinant FVIII with 20 kDa PEG | US: all; EU: ≥12 years | Adolescents/adults: 40-50 IU/kg 2 times weekly; children <12 years: 55 IU/kg 2 times weekly | One stage or chromogenic |

| Jivi® (damoctocog alfa pegol) | B-domain deleted FVIII with 60 kDa PEG | US & EU: ≥12 years | 30–40 IU/kg twice weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Esperoct® (turoctocog alfa pegol) | B-domain truncated FVIII with 40 kDa PEG | US: all; EU: ≥12 years | Adolescents/adults: 50 IU/kg every 4 days; children <12 years: 65 IU/kg twice weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Afstyla® (lonoctocog alfa) | Single-chain recombinant FVIII | US & EU: all ages | Adults: 20-50 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly; children <12 years: 30-50 IU/kg 2-3 times weekly | Chromogenic assay |

| Factor IX products | ||||

| Alprolix® (efrenonacog alfa) | Recombinant FIX fused to Fc portion of IgG1 | US & EU: all ages | Adolescents/adults: 50 IU/kg weekly or 100 IU/kg every 10 days; children <12 years: 60 IU/kg weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

| Idelvion® (albutrepenonacog alfa) | Recombinant FIX fused to albumin | US & EU: all ages | Adolescents/adults: 25-40 IU/kg weekly; children <12 years: 40-55 IU/kg weekly | One stage with validated reagents† |

| Rebinyn®/Refixia® (nonacog beta pegol) | Recombinant FIX with 40 kDa PEG | EU: ≥12 years | 40 IU/kg weekly | Chromogenic or one stage with validated reagents† |

Recommended doses based on US package insert except for Refixia®, which is licensed for prophylaxis use in the EU only.

The availability of EHL CFCs has decreased the treatment burden, especially for patients with HB, leading to high adherence rates for prophylaxis.53 The prolonged half-life of EHL CFCs translates to dosing twice per week or every 4 days for FVIII CFC and once every 7 to 14 days for FIX CFC. The discrepancy in dosing intervals is due to the dependence of FVIII on the half-life of its chaperone VWF; thus, the prolonged half-life is modest at 1.5 to 1.7 times the half-life of SHL FVIII CFC. This limitation has been overcome by a new class of FVIII that builds on the Fc fusion technology by adding a region of VWF and XTEN® polypeptides, physically decoupling it from endogenous VWF.54 Early-phase clinical studies demonstrated a 3- to 4-fold increase in half-life observed, possibly reducing the dosing frequency of FVIII for prophylaxis to once a week.55 Phase 3 clinical trials are ongoing, with results expected in 2022 (NCT04161495).

In selected HA patients who require higher trough levels, a switch to EHL CFCs administered at the regular dose interval (ie, every other day) used for SHL CFCs may be appropriate. The presumed benefit predicted from targeting higher trough levels was confirmed in the recently published PROPEL study that randomized 115 severe HA patients on prophylaxis factor replacement therapy using rurioctocog alfa pegol (an EHL product with a half-life of 14 to 16 hours) to 2 FVIII trough levels, 1% to 3% vs 8% to 12%.56 As expected, during the 6-month study period 85% of patients in the higher-trough arm achieved zero spontaneous joint bleeds vs 65% in the lower-trough arm. However, achieving the higher target trough levels required a higher burden of therapy, with 72.4% needing infusion every 24 to 48 hours vs 19.3% in the lower-trough arm. Notably, 60% of patients in the lower-trough arm experienced zero spontaneous bleeds, whereas 24% of those in the higher-trough arm continued to have spontaneous bleeds. This supports 2 key points: (1) bleeding events decrease as target trough factor level increases, and (2) there is a need for personalized treatment. The latter indirectly answers the question that the appropriate target trough level is that at which the patient experiences zero bleeds while preserving an active (or sedentary) lifestyle.

Individual PK assessment

For patients with HA, there is a wide variation of interpatient PK handling of infused factor dependent on age, body mass, blood group, and VWF levels.57-60 PK studies on interpatient handling of FIX CFC have been fewer, but it is thought to have similar interpatient variability.61,62 Hence, to optimize prophylaxis and factor utilization, the WFH currently recommends individualized PK assessment.9

Traditionally, obtaining PK evaluation was a huge inconvenience due to the need for a washout period (abstaining for 72 hours from FVIII CFC use and 96-120 hours for FIX CFC use, thus introducing ethical concerns for increased bleeding risk) and frequent factor measurements for 48 to 72 hours after infusion of a prophylaxis dose. Nowadays, the availability of population-based PK models, such as WAPPS-Hemo (www.wapps-hemo.org), enables a Bayesian estimation of individual PK from only 2 or 3 factor measurements without a washout period and allows for the increased use of PK monitoring in routine clinical practice.63,64 A practical guide for adopting PK assessment in the clinic is shown in Table 5.

A practical guide for adopting PK assessment in the clinic

| Question . | Answer . |

|---|---|

| How should I schedule the clinic visit? | Time/day of infusion and clinic visit should be coordinated to ensure factor levels can be drawn at required time points to minimize multiple patient visits and inconvenience |

| What are the ideal measurement time points?* | For SHL FVIII – predose, 2-4 hours, 24 ± 4 hours, 48 ± 6 hours; for SHL FIX – predose, any time on day 2 and 3; for EHL – as above and add a time point at 60-84 hours for FVIII and at 2-14 days for FIX |

| What population PK software is available? | A globally accessible online tool, such as WAPPS-Hemo, or product-specific tools by the product manufacturers |

| What information is required?* | Age, baseline factor level, product name, total dose administered, body weight, height, infusion day, infusion time, postinfusion factor levels, and timing of samples |

| What do I do with the results? | Share and explain results with patients/caregivers; tailor treatment regimen based on results, if appropriate; integrate results into patient's medical records |

| Question . | Answer . |

|---|---|

| How should I schedule the clinic visit? | Time/day of infusion and clinic visit should be coordinated to ensure factor levels can be drawn at required time points to minimize multiple patient visits and inconvenience |

| What are the ideal measurement time points?* | For SHL FVIII – predose, 2-4 hours, 24 ± 4 hours, 48 ± 6 hours; for SHL FIX – predose, any time on day 2 and 3; for EHL – as above and add a time point at 60-84 hours for FVIII and at 2-14 days for FIX |

| What population PK software is available? | A globally accessible online tool, such as WAPPS-Hemo, or product-specific tools by the product manufacturers |

| What information is required?* | Age, baseline factor level, product name, total dose administered, body weight, height, infusion day, infusion time, postinfusion factor levels, and timing of samples |

| What do I do with the results? | Share and explain results with patients/caregivers; tailor treatment regimen based on results, if appropriate; integrate results into patient's medical records |

Ideal time points and information required are based on WAPPS-Hemo (www.wapps-hemo.org). Please see product manufacturers' manual if using product-specific tools. Adapted with permission from Hermans C, Dolan G. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology (Volume 11).66 © The Author(s), 2020; Reprinted by Permission of SAGE Publications.

A typical PK profile contains many PK parameters, including area under the curve, in vivo recovery, half-life, and clearance. Detailed descriptions of these PK parameters are described in recently published review articles by Delavenne and Dargaud, Hermans and Dolan, and Iorio.65-67 Practically, the most important estimates in the PK profile are the time to a targeted (or trough) factor level or the factor level at a specific time after the infusion.64,65,67 One can then simulate the effect of using different doses and/or infusion frequencies to achieve the desired factor level or to determine the appropriateness of performing a physical activity given the factor level at a specific time. In my experience, the ability to determine the latter has provided significant peace of mind to hemophilia patients with active lifestyles.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

We discussed switching to the EHL version of the patient's current SHL CFC. He declined to undergo a PK assessment on his current SHL regimen but was agreeable to doing so after switching. He was started on an EHL CFC at 50 IU/kg once every 4 days. After 2 months on the new regimen, he came to the clinic for a PK evaluation that showed a half-life of 16.25 hours and an estimated trough level of 3.3% prior to the next dose. One year later, he reports zero spontaneous joint bleeds.

Monitoring real-world hemostatic effectiveness

Even though all available CFCs have been shown to be efficacious in clinical trials, continuous monitoring of hemostatic outcomes in clinical practice is recommended. Recently, it has been reported that a small subset of HB patients on EHL FIX CFCs for prophylaxis experienced unexpected spontaneous breakthrough bleeding despite adequate FIX levels.68,69 These patients had to switch back to SHL CFCs, switch to a different EHL CFC, or reduce the dosing interval from 14 days to 7 to 10 days to maintain adequate hemostatic control. The cause of this unexpected hemostatic outcome remains unclear, and further research is warranted.68,69 Yet this highlights the need for continuous assessment of real-world hemostatic outcomes outside of clinical trials when newly approved treatment options for hemophilia are introduced in routine clinical practice.

Conclusion

In the era of precision medicine, it is clear that prophylaxis factor replacement therapy should be individualized for optimal factor utilization and that “one regimen does not fit all.” Different aspects of the treatment, including product type, dose, and interval, as well as targeted trough levels and bleeding triggers, are involved in tailoring the regimen to the clinical needs of the patient. One aspect not explicitly discussed is that effective prophylaxis is an ongoing collaborative effort that relies on shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician. All of the aforementioned considerations are irrelevant if the patient's preferences and values are not taken into account. As the complexity of treatment options increases with the availability of nonfactor therapies and gene therapy, it is critical that both patients and clinicians are actively involved in this collaborative process to optimize treatment and overall patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

Ming Y. Lim received a 2018 Mentored Research Award from the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society, which was supported by an educational grant from Bioverativ, a Sanofi company.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Ming Y. Lim: honorarium for participation in advisory boards: Sanofi Genzyme, Argenx, Dova Pharmaceuticals, Hema Biologics; honorarium and travel expenses for educational participation: Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society Trainee Workshop supported by Novo Nordisk.

Off-label drug use

Ming Y. Lim: nothing to disclose.