Abstract

Although risk for relapse may be the greatest concern following recovery from acquired, autoimmune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), there are multiple other major health issues that must be recognized and appropriately addressed. Depression may be the most common disorder following recovery from TTP and may be the most important issue for the patient’s quality of life. Severe or moderate depression has occurred in 44% of Oklahoma Registry patients. Recognition of depression by routine screening evaluations is essential; treatment of depression is effective. Minor cognitive impairment is also common. The recognition that cognitive impairment is related to the preceding TTP can provide substantial emotional support for both the patient and her family. Because TTP commonly occurs in young black women, the frequency of systemic lupus erythematosus, as well as other autoimmune disorders, is increased. Because there is a recognized association of TTP with pregnancy, there is always concern for subsequent pregnancies. In the Oklahoma Registry experience, relapse has occurred in only 2 of 22 pregnancies (2 of 13 women). The frequency of new-onset hypertension is increased. The most striking evidence for the impact of morbidities following recovery from TTP is decreased survival. Among the 77 patients who survived their initial episode of TTP (1995-2017), 16 (21%) have subsequently died, all before their expected age of death (median difference, 22 years; range 4-55 years). The conclusion from these observations is clear. Following recovery from TTP, multiple health problems occur and survival is shortened. Therefore, careful continuing follow-up is essential.

Learning Objectives

Recognize depression and minor cognitive impairment in patients following recovery from TTP

Recognize the risk for occurrence of additional autoimmune disorders following recovery from TTP

Recognize that subsequent pregnancy is uncommonly associated with recurrent TTP

Recognize that continuing follow-up is essential to recognize and manage health issues related to the acute TTP episode

Introduction

Twenty-five years ago, I believed that thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP; acquired autoimmune) was always a one-time disorder. When patients recovered, their blood counts were normal. Therefore, I assumed that they were normal. This was when plasma exchange had recently transformed TTP from a fatal1 to a treatable2 disorder and before the occurrence of relapses was reported.3 At this time, I began to work with the Oklahoma Blood Institute to see patients for whom plasma exchange was requested for a diagnosis of TTP. The diagnosis was often uncertain. Our goal was to learn whom to treat and how long to treat. Then, in 1995, one of my patients, a home health nurse, told me that following her recovery she had problems with fatigue and forgetfulness that limited her ability to work. I was surprised. She asked if we could begin a TTP Support Group. I thought this was a bad idea. I thought that patients who had recovered from TTP needed to forget about TTP. But I agreed and we began.4,5 Then, I was surprised again to learn from the stories of multiple patients at our TTP Support Group meetings that their problems following recovery were real. So, we began the studies of Oklahoma Registry patients during remission.

This review summarizes what we and others6-10 have learned about long-term outcomes following recovery from TTP. I will present our experience with depression, cognitive impairment, occurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disorders, pregnancy outcomes, kidney function, and death. I will not discuss relapse and the related issues of ADAMTS13 activity measurements during remission and preemptive treatment with rituximab.

Depression

SIGECAPS is the mnemonic that medical students memorize to learn the symptoms of depression: sleep, interest, guilt, energy, concentration, appetite, psychomotor retardation, and suicide.11 Depression is critically important because it is common, it is serious (potentially fatal), and it can be effectively treated, but it is strongly stigmatized so that people are reluctant to seek help. Because everyone has some of these symptoms at times of stress (except, of course, feeling worthless to the extent of considering suicide), I did not suspect depression among our patients. I thought the symptoms that our patients were describing were the result of cognitive impairment because the symptoms can be similar. When we first tested our patients for cognitive ability in 2004, we used a screening test for depression as a control. Then, I was surprised again to learn that many of our patients had undiagnosed moderate or severe depression.

Depression following recovery from TTP became our major concern, and screening for depression became an annual routine. The standard and most commonly used questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), which asks 8 simple questions about symptoms during the previous 2 weeks. It can be completed in several minutes.12 Nearly half of our patients (44%) have been documented to have moderate or severe depression at some time following their recovery from TTP (Table 1). Few of these patients had a previous diagnosis of depression. Other hematologists have reported similar frequencies of moderate or severe depression.7,9,10 Chaturvedi et al10 also reported criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder in 35% of patients following recovery from TTP.

Depression and cognitive impairment following recovery from TTP

| Interpretation . | Patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Depression* | |

| Minimal/none | 21 (41) |

| Mild | 8 (15) |

| Moderate | 8 (15) |

| Severe | 15 (29) |

| Cognitive ability† | |

| High average/superior | 3 (8) |

| Low average/average | 26 (72) |

| Extremely low/borderline | 7 (20) |

| Interpretation . | Patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Depression* | |

| Minimal/none | 21 (41) |

| Mild | 8 (15) |

| Moderate | 8 (15) |

| Severe | 15 (29) |

| Cognitive ability† | |

| High average/superior | 3 (8) |

| Low average/average | 26 (72) |

| Extremely low/borderline | 7 (20) |

Depression screening was performed by the Beck Depression Index-II (BDI-II) in 52 patients following their recovery from TTP from 2004 to 2014. Individual patients were tested 1 to 6 times. Levels of depression were assigned according to BDI-II criteria. The results are reported as severe (on ≥1 screening test), moderate (on ≥1 screening test but never severe), mild (on ≥1 screening test but never moderate or severe), and minimal/none (on all screening tests). Patients with severe depression have also been evaluated by a psychiatric interview to confirm the diagnosis of major depressive disorder.17

Cognitive testing was performed with the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) in 36 patients following their recovery from TTP (2014). Five individual domains were assessed: immediate memory, delayed memory, attention, language, and visuospatial ability. Levels of cognitive ability were assigned according to normal population values adjusted for age.17

Although the frequency of depression following recovery from TTP is significantly increased compared with the US population, adjusted for age, race, sex, and body mass index (BMI),13 we do not believe that depression among our patients is distinct from depression in the US population. The clinical features, treatment, and response to treatment appear to be the same. The occurrence of severe depression in our patients was not related to the severity or the occurrence of stroke and seizures with their preceding TTP episode or to the number of preceding episodes.13

Among 43 patients who had multiple annual screening evaluations for depression, 10 always had no depression and were not taking antidepressant medication (on 2-6 annual evaluations; median, 4.5). Among the other 33 patients, 3 consistently had severe depression; 2 were taking antidepressant medication. The depression scores were variable in the other 30 patients, with or without antidepressant medication, and the variability was not related to the time since their acute episode(s) of TTP.

Our experience documents what others have eloquently described. Depression is dangerous. It erodes quality of life and personal productivity. It is often unrecognized. Most importantly, it can be effectively treated.11,14 With current antidepressant medications and mental health support, 67% of patients with severe depression will achieve a remission (no clinically important symptoms); 74% of patients with depression will experience a clinical response.15 However, a common and critical problem is that many patients are reluctant to admit that they are depressed and they do not ask for treatment (D. R. Terrell, E. L. Tolma, L. M. Stewart, and E. A. Shirley, manuscript in preparation).9,11

Cognitive impairment

SIGECAP (no S at the end). The symptoms of minor cognitive impairment are similar to the symptoms of depression, except for the risk of suicide. Similar to depression, patients may dismiss their problems with concentration, memory, and fatigue as only a normal part of their lives. It was during the discussions at our support group meetings that our former patients and their families recognized that others in the group also had these symptoms and that they had occurred following their recovery from TTP. Then, the patients focused on convincing me that these symptoms were real. This was the beginning of our studies to document cognitive impairment (Table 1). The patients were eager to participate and to document that their problems with concentration, memory, and fatigue were real. When we learned that the cognitive abnormalities did not improve with time following recovery, the patients were not distressed, they were relieved. They already knew that their symptoms did not improve with time. In fact, we have documented that patients’ problems with immediate and delayed memory can become significantly worse with follow-up evaluations.16,17 Although our tests of cognitive function clearly demonstrate that our patients, as a group, perform less well than established normal values, only a few patients are actually defined as abnormal (>1 standard deviation below the age-, sex-, education-adjusted US normal population data). This is consistent with the observation that almost all of our patients have continued their previous occupations.

Although the symptoms of cognitive impairment and depression can be similar, the patients’ scores on the 2 evaluations were not correlated and did not support an association between cognitive impairment and depression.16 However, Falter et al9 have demonstrated a correlation between severity of depression and cognitive performance. The interaction between major depression and cognitive impairment has also been documented in patients following traumatic brain injury.18

In our studies, neither depression nor cognitive ability were significantly different related to race, sex, level of education, number of TTP episodes, or level of ADAMTS13 activity during remission, although the number of patients was small.16 Also, cognitive impairment was not related to the occurrence of severe neurologic abnormalities during the preceding episode of TTP.17

Patients’ acceptance of the diagnosis of cognitive impairment contrasts with patients’ reluctance to accept a diagnosis of depression. In contrast to depression, there is no specific treatment of cognitive impairment. But there are adaptive strategies that can help patients to compensate for their limitations. Screening for cognitive impairment can be performed simply with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; www.mocatest.org) questionnaire, a freely available 5- to 10-minute test for immediate memory, delayed memory, attention, language, visuospatial ability, and executive function.19 Our experience is that the results of the MoCA test were comparable to the more extensive evaluation of cognitive function by the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) test.16

Systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disorders

The occurrence of additional autoimmune disorders in patients with TTP is increased. The French National Registry has reported that additional autoimmune disorders occurred in 56 of 261 patients (21%) with TTP.20 The most common additional autoimmune disorder was systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which occurred in 26 patients (10%). SLE was diagnosed before (7 patients) or concurrently with the diagnosis of TTP (11 patients) or following recovery (8 patients). The most common among the other autoimmune disorders were Sjögren syndrome (8 patients) and thyroiditis (5 patients).

We have also diagnosed SLE in 10 of our 89 patients (11%), and the diagnoses were also made before or concomitantly with the diagnosis of TTP or following recovery. Our patients with TTP are predominantly young black women (Table 2),21 which are also the main demographic features of patients with SLE.22 The prevalence of SLE in our patients (11%) is 37-fold greater than the expected prevalence of 0.3% among age-, race-, sex-matched subjects.13 We have also diagnosed multiple other autoimmune disorders in our patients, including Graves disease, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, Addison disease, acquired factor VIII inhibitor, polymyositis, scleroderma, and Sjögren syndrome.

Demographic features of 89 Oklahoma TTP patients, 1995-2017

| Feature . | Data . |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 40 (9-78) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 67 (75) |

| Race, black, n (%) | 35 (39) |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | >40, 21 (24) |

| Feature . | Data . |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 40 (9-78) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 67 (75) |

| Race, black, n (%) | 35 (39) |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | >40, 21 (24) |

Data for age and BMI are from the day of diagnosis of the initial episode of TTP. Compared with the population of the 58 counties included in the Oklahoma TTP Registry region, the standardized TTP incidence rate was sevenfold higher in blacks compared with nonblacks for the 72 patients enrolled through 2012, when the frequency of black patients was 36%.21 The patients’ BMI was significantly greater than the expected US values based on age, race, and sex values obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (P < .001). The frequency of BMI > 40 kg/m2 in the age-, race-, and sex-adjusted US population is 9%. A BMI of 40 kg/m2 is equivalent to a person 5 feet 6 inches tall, weighing 250 pounds.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy often, maybe always, causes the occurrence of an acute episode of TTP in women with hereditary TTP.23-26 Pregnancy is also an issue in acquired TTP because acquired TTP is predominantly a disorder of young women (Table 2). Among the 47 women in the Oklahoma Registry (1995-2018) who were <50 years old at the time of their initial episode of TTP, the initial episode was associated with pregnancy in 5 women (11%). In these 5 women, TTP occurred at 8 weeks’ gestation, at delivery, and at 9, 13, and 45 days postpartum. Because of the association of TTP and pregnancy, consideration of a subsequent pregnancy is a complex and emotional issue. Table 3 presents our experience. Thirteen women have had 22 subsequent pregnancies; 2 were associated with a relapse of TTP, occurring 9 and 29 days postpartum. These data are similar to the experience reported by Scully et al.26 Excluding the woman who had 2 pregnancies with first-trimester fetal loss (Table 3 woman 2), preeclampsia occurred in 4 of 12 women (33%), 6 of 20 pregnancies (30%), exceeding the expected frequency of preeclampsia.27

Outcomes of 13 women with 22 pregnancies following recovery from TTP

| Woman . | Pregnancy . | Pregnancy outcome . | Child outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Normal | Normal |

| 2 | Normal | Normal | |

| 2 | 3 | 13 wk fetal loss | NA |

| 4 | 12 wk fetal loss | NA | |

| 3 | 5 | Normal | Normal |

| 6 | Normal | Normal | |

| 4 | 7 | Severe preeclampsia | Normal |

| 8 | Severe preeclampsia | Normal | |

| 5 | 9 | Normal | Normal |

| 10 | Normal | Normal | |

| 6 | 11 | Preeclampsia | Normal |

| 12 | Preeclampsia, TTP relapse 29 d postpartum | Normal | |

| 7 | 13 | Severe preeclampsia, TTP relapse 9 d postpartum | Normal |

| 8 | 14 | 20 wk fetal loss | NA |

| 15 | Normal | Normal | |

| 16 | Normal | Normal | |

| 9 | 17 | Normal | Normal |

| 10 | 18 | SLE flare | Normal |

| 11 | 19 | Normal | Normal |

| 20 | Normal | Normal | |

| 12 | 21 | Fetal growth retardation, delivery at 26 wk | Died, sepsis |

| 13 | 22 | Preeclampsia | Normal |

| Woman . | Pregnancy . | Pregnancy outcome . | Child outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Normal | Normal |

| 2 | Normal | Normal | |

| 2 | 3 | 13 wk fetal loss | NA |

| 4 | 12 wk fetal loss | NA | |

| 3 | 5 | Normal | Normal |

| 6 | Normal | Normal | |

| 4 | 7 | Severe preeclampsia | Normal |

| 8 | Severe preeclampsia | Normal | |

| 5 | 9 | Normal | Normal |

| 10 | Normal | Normal | |

| 6 | 11 | Preeclampsia | Normal |

| 12 | Preeclampsia, TTP relapse 29 d postpartum | Normal | |

| 7 | 13 | Severe preeclampsia, TTP relapse 9 d postpartum | Normal |

| 8 | 14 | 20 wk fetal loss | NA |

| 15 | Normal | Normal | |

| 16 | Normal | Normal | |

| 9 | 17 | Normal | Normal |

| 10 | 18 | SLE flare | Normal |

| 11 | 19 | Normal | Normal |

| 20 | Normal | Normal | |

| 12 | 21 | Fetal growth retardation, delivery at 26 wk | Died, sepsis |

| 13 | 22 | Preeclampsia | Normal |

Sixteen pregnancies in women 1 through 10 were previously reported.27 Women 5 and 8 have had an additional normal pregnancy since this previous publication. No women received prophylactic treatments for TTP (eg, rituximab) preceding or during their pregnancies. Women 1, 3, 9, and 13 each had 1 previous pregnancy that was associated with their initial episode of TTP, occurring at 7 weeks’ gestation, the day of delivery, postpartum day 9 and postpartum day 45. Only woman 9 has had relapse episodes of TTP following these pregnancies; she had 2 relapses (not associated with a pregnancy) 25 and 35 months following her normal pregnancy. Woman 12 is currently pregnant, due in September 2018.

NA, child outcome when fetal loss occurred before the gestational age of viability.

Based on this experience, I do not discourage subsequent pregnancies. Although we have not previously measured ADAMTS13 activity preceding pregnancy to assess risk for relapse, this is now becoming a common practice.26 If a severe deficiency of ADAMTS13 activity (<10%-20%) is present, preemptive treatment with 1 infusion of rituximab (375 mg/m2) may be effective and appropriate to increase ADAMTS13 activity and prevent the occurrence of relapse during pregnancy.28,29

Kidney function

TTP is unique among the primary thrombotic microangiopathy syndromes because it tends to cause less kidney injury during acute episodes.30 Our patients have rarely had severe acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD).31,32 At follow-up (median, 5 years after the initial TTP episode), the estimated glomerular filtration rate of our patients was not different from age-, race-, sex-, and BMI-matched normal subjects.13 However, microalbuminuria (≥10 mg/g creatinine), which predicts increased risk for hypertension33 and death,34,35 was significantly increased among our patients.36

The presence of severe AKI during the acute episode of TTP was not related to the development of CKD. Among the 8 patients with the most severe Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI stage 3, 3 died during their initial TTP episode. Among the 5 surviving patients, who have been followed for 3 to 16 years, all have normal estimated glomerular filtration rate (4 patients: ≥90 mL per minute per 1.73 m2; 1 patient: 77 mL per minute per 1.73 m2). Among the 4 patients who did develop CKD (following AKI stages 0-2), 2 had preexisting hypertension, 1 had preexisting diabetes, and 1 had both preexisting hypertension and diabetes.32

Even though the severity of AKI was not associated with the development of CKD, it was associated with the development of hypertension and the occurrence of death following recovery from TTP. Although only 21% of our patients had KDIGO AKI stage 2 or 3, these patients accounted for 38% of the patients (6 of 16) with new-onset hypertension and 54% of the deaths (7 of 13 patients) (Table 4). These data emphasize the importance of routine blood pressure measurements to diagnose and effectively treat hypertension.

Relation of AKI during the initial TTP episode to the frequency of new-onset hypertension and death following recovery

| Outcome . | Patients (%) . | |

|---|---|---|

| KDIGO AKI stage 0-1 . | KDIGO AKI stage 2-3 . | |

| New-onset hypertension | 10/43 (23) | 6/9 (67) |

| Death | 6/52 (12) | 7/14 (50) |

| Outcome . | Patients (%) . | |

|---|---|---|

| KDIGO AKI stage 0-1 . | KDIGO AKI stage 2-3 . | |

| New-onset hypertension | 10/43 (23) | 6/9 (67) |

| Death | 6/52 (12) | 7/14 (50) |

AKI was calculated by KDIGO criteria. KDIGO stages 0-1: serum creatinine (SCr) increase <2× baseline; stages 3-4: SCr increase ≥2× baseline. These data describe our experience from 1995 to 2015. Among 78 patients, 68 survived their initial episode; 2 patients had been lost to follow-up. Therefore, 66 patients were included in these data (median follow-up, 7 years).32 Fourteen of the 66 patients had hypertension preceding their initial episode of TTP and were therefore not included in the analysis for new-onset hypertension; the median follow-up of the 52 remaining patients was 5.5 years. When each of the 4 individual KDIGO stages was analyzed separately, the frequencies of new-onset hypertension (P = .023) and death (P = .015) were greater among patients with more severe AKI.32

Death

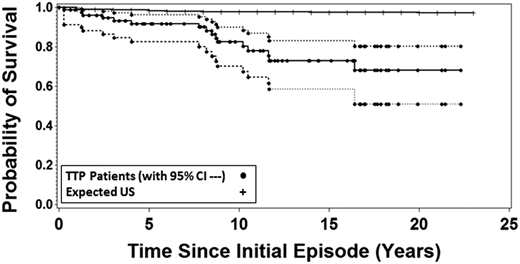

In our report of long-term outcomes following recovery from TTP in 2013, we reported that 11 of 57 patients (19%) who had survived their initial episode had subsequently died. The survival of these 57 patients was significantly and substantially less than the survival of the age-, race-, and sex-matched US population.13 I was surprised again. Although I had followed all of our patients since their initial episode and of course I knew about the individual deaths, I did not expect these data. Now, 6 years later, 16 of 77 surviving patients (21%) have died following recovery from TTP, all before their expected age at death (median difference, 22 years; range, 4-55 years). The survival of our patients was again significantly and substantially less than the survival of the age-, race-, and sex-matched US population (Figure 1).

Sixteen of the 77 patients who recovered from their initial episode of TTP (1995-2017) have subsequently died. The probability of patient survival is compared with the expected probability based on the matched age-, race-, and sex-specific mortality rates from the reference US population obtained from the data of the Centers for Disease Control. Broken lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals around the patient survival. The probability of patient survival and 95% confidence intervals as well as the population probability of death for the United States were calculated using Kaplan-Meier methods with pointwise limits.

Sixteen of the 77 patients who recovered from their initial episode of TTP (1995-2017) have subsequently died. The probability of patient survival is compared with the expected probability based on the matched age-, race-, and sex-specific mortality rates from the reference US population obtained from the data of the Centers for Disease Control. Broken lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals around the patient survival. The probability of patient survival and 95% confidence intervals as well as the population probability of death for the United States were calculated using Kaplan-Meier methods with pointwise limits.

The causes of the deaths for these 16 patients were diverse. Two occurred at the time of a relapse.31 Six deaths may also be directly attributable to the preceding TTP: 4 were related to cardiac disease associated with hypertension or cardiomyopathy; 2 were attributed to stroke. Three deaths were related to other autoimmune disorders: 2 patients with SLE died with pneumonia; 1 woman with scleroderma had intestinal fistulas and sepsis. The causes of death in the remaining 5 patients seem unrelated to TTP: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2), IV drug abuse with sepsis, ovarian carcinoma, and hemorrhage related to anticoagulation for her prosthetic aortic valve.

Deaths may be related to morbidities caused by the previous TTP episode(s). AKI at the time of the initial TTP episode, even if it was not severe, was an important predictor for morbidity and mortality following recovery. However, the demographic characteristics of people who acquire TTP are also risk factors for death. Perhaps most important is the striking increase of obesity among our patients with TTP (Table 2). Obesity has a strong association with all-cause mortality.37,38

Summary

Our experience documents that acquired, autoimmune TTP is more than an acute disorder. Although risk for relapse may be the greatest concern for patients who have recovered from TTP, there are many other important reasons for continuing careful follow-up. Depression may be the most common and most debilitating disorder that occurs following recovery from TTP. Regular screening for depression is essential and simple; treatment of depression may be the most important contribution to the patient’s quality of life. Although there is no effective treatment of cognitive impairment, there are multiple opportunities for supportive care. SLE and many other autoimmune disorders may occur following recovery. New-onset hypertension is common and must be recognized and treated. Managing patients following recovery from TTP provides a comprehensive review of psychiatry, obstetrics, and internal medicine.

Correspondence

James N. George, College of Public Health, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 801 NE 13th St, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; e-mail: james-george@ouhsc.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict of interest: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.