Abstract

Mastocytosis is a unique and rare neoplasm defined by abnormal expansion and accumulation of clonal mast cells (MCs) in one or multiple organ systems. Most adult patients are diagnosed to have systemic mastocytosis (SM). Based on histological findings and disease-related organ damage, SM is classified into indolent SM (ISM), smoldering SM (SSM), SM with an associated hematologic non-MC-lineage disease (SM-AHNMD), aggressive SM (ASM), and MC leukemia (MCL). The clinical picture, course, and prognosis vary profoundly among these patients. Nonetheless, independent of the category of SM, neoplastic cells usually exhibit the KIT point-mutation D816V. However, in advanced SM, additional molecular defects are often detected and are considered to contribute to disease progression and drug resistance. These lesions include, among others, somatic mutations in TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, CBL, RUNX1, and RAS. In SM-AHNMD, such mutations are often found in the “AHNMD component” of the disease. Clinical symptoms in mastocytosis result from (1) the release of proinflammatory and vasoactive mediators from MCs, and (2) SM-induced organ damage. Therapy of SM has to be adjusted to the individual patient and the SM category: in those with ISM and SSM, the goal is to control mediator secretion and/or mediator effects, to keep concomitant allergies under control, and to counteract osteoporosis, whereas in advanced SM (ASM, MCL, and SM-AHNMD) anti-neoplastic drugs are prescribed to suppress MC expansion and/or to keep AHNMD cells under control. Novel drugs directed against mutated KIT and/or other oncogenic kinase targets are tested currently in these patients. In rapidly progressing and drug-resistant cases, high-dose polychemotherapy and stem cell transplantation have to be considered.

Learning Objectives

To understand the biology and pathogenesis of mastocytosis

To establish the correct diagnosis in patients with suspected mastocytosis

To manage patients with mastocytosis in various categories of the disease

To establish the correct treatment plan for patients with indolent and advanced systemic mastocytosis (SM)

To review novel emerging targeting concepts and treatment options in SM

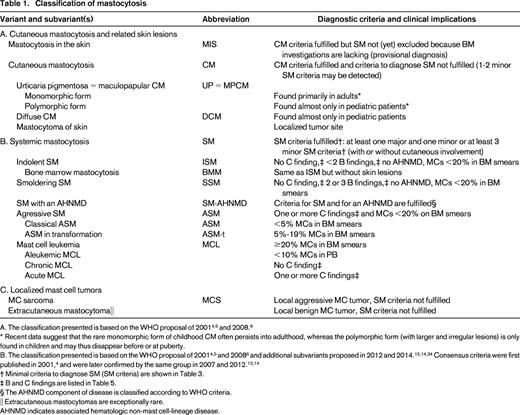

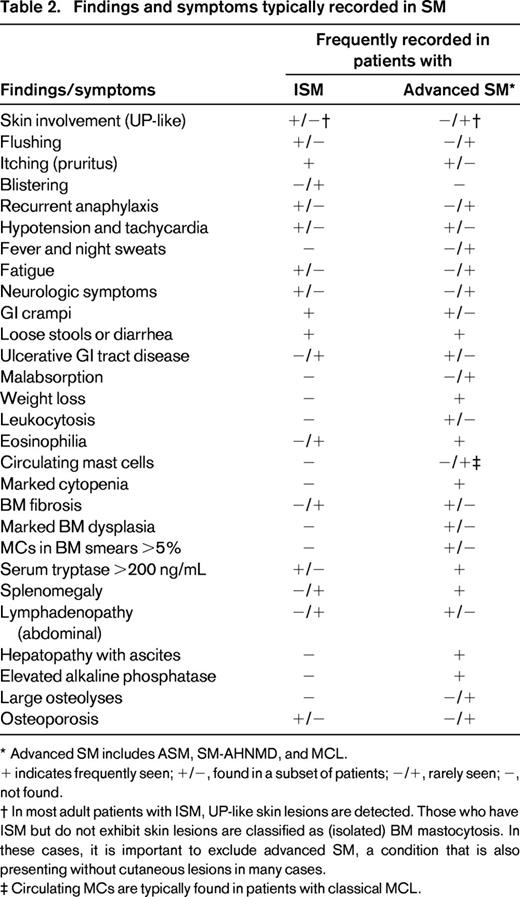

Mastocytosis is a rare condition characterized by abnormal expansion and accumulation of neoplastic mast cells (MCs) in various organ systems, including the skin, bone marrow (BM), spleen, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.1-4 Depending on the affected organ system(s), mastocytosis can be divided into cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), systemic mastocytosis (SM), and localized MC tumors.4-6 The classification of the Consensus Group and the World Health Organization (WHO) discriminates between several distinct subvariants of CM and SM (Table 1).4-6 The prognosis, course, and survival diverge substantially among these patient-cohorts.7-9 Moreover, symptoms caused by MC-derived mediators are often recorded, especially when patients suffer from a concomitant immunoglobulin E (IgE)–dependent allergy.10-14 Such mediator-induced symptoms may be mild, extensive, or even life-threatening. In those with severe anaphylaxis, serum tryptase levels increase substantially above (individual) baseline levels, and a so-called MC-activation syndrome may be detected.13-15 In addition, SM patients may suffer from osteopathy, often in the form of advanced osteopenia or osteoporosis but also from neurologic or psychiatric problems, GI symptoms, or/and from dermatologic problems, such as flushing, itching, or blistering (Table 2).1-4,12 In aggressive SM (ASM) and MC leukemia (MCL), additional, clinically relevant features may be present, such as marked cytopenia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, hypalbuminemia, malabsorption, or large osteolyses (Table 2).3-8 Whereas in patients with CM and indolent SM (ISM) the prognosis is excellent with almost normal life expectancy, the prognosis in ASM and MCL is poor.7-9 Although regarded as a hematologic neoplasm, the management of SM often requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving dermatologists, hematologists, pathologists, and immunologists. This article provides a state-of-the-art overview on the pathogenesis, classification, and management of patients with mastocytosis.

Classification of mastocytosis

* Recent data suggest that the rare monomorphic form of childhood CM often persists into adulthood, whereas the polymorphic form (with larger and irregular lesions) is only found in children and may thus disappear before or at puberty.

B. The classification presented is based on the WHO proposal of 20014,5 and 20086 and additional subvariants proposed in 2012 and 2014.12,14,34 Consensus criteria were first published in 2001,4 and were later confirmed by the same group in 2007 and 2012.12,14

† Minimal criteria to diagnose SM (SM criteria) are shown in Table 3.

‡ B and C findings are listed in Table 5.

§ The AHNMD component of disease is classified according to WHO criteria.

|| Extracutaneous mastocytomas are exceptionally rare.

AHNMD indicates associated hematologic non-mast cell-lineage disease.

Findings and symptoms typically recorded in SM

* Advanced SM includes ASM, SM-AHNMD, and MCL.

+ indicates frequently seen; +/−, found in a subset of patients; −/+, rarely seen; −, not found.

† In most adult patients with ISM, UP-like skin lesions are detected. Those who have ISM but do not exhibit skin lesions are classified as (isolated) BM mastocytosis. In these cases, it is important to exclude advanced SM, a condition that is also presenting without cutaneous lesions in many cases.

‡ Circulating MCs are typically found in patients with classical MCL.

Incidence and prevalence

In general, mastocytosis is considered a rare disease. However, no solid data on incidence and prevalence of CM or SM have been collected yet. Hence, during the past 2 decades, the number of well-documented cases of SM increased substantially in the United States and Europe. This may be attributable to improved diagnostics and algorithms, emerging awareness in the public, and better knowledge of physicians.16 The European Competence Network on Mastocytosis has recently established a patient registry, with the aim to study the epidemiology, course, and prognosis in CM and SM.16

So far, no clear gender predominance has been reported in CM or SM. Although rare familial cases have been described, mastocytosis is considered a nonhereditary, somatic disorder. Mastocytosis is diagnosed in two distinct age groups: (1) (early) childhood; and (2) adulthood.1-6 Most childhood patients are suffering from CM.1-6 In many, but not all, of them, skin lesions disappear at or around puberty. So far, no solid prognostic indicator predicting disease persistence has been identified. However, recent data suggest that childhood patients with monomorphic, small-sized maculopapular skin lesions tend to develop persistent disease, whereas polymorphic skin lesions often disappear before adolescence.17,18 Adulthood SM is regarded a persistent disease without spontaneous remission.1-6,17,18 In patients who do not develop skin lesions, SM either remains indolent and undetected for many years (occult SM) or the disease is aggressive.1,4-6,12 In fact, patients with ASM or MCL often present without skin lesions.3-6

Biology, history, and classification

MCs are tissue-fixed effector cells of inflammatory and allergic reactions. These cells express a plethora of vasoactive and proinflammatory mediators in their granules and high-affinity IgE-binding sites.1-3 MCs are derived directly from hematopoietic progenitors that can be detected in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB).2-4 Uncommitted and MC-committed progenitors express KIT, an MC-related receptor kinase.1-3 The ligand of this receptor, stem cell factor (SCF), initiates the development of MCs from their uncommitted and MC-committed precursor cells.2-4 In patients with mastocytosis, SCF-independent differentiation and accumulation of MCs is typically found.2-4

Mastocytosis was described initially as a dermatologic condition termed urticaria pigmentosa (UP). Indeed, most patients with SM present with typical maculopapular skin lesions. However, absence of UP-like skin lesions does not exclude SM. In 1949, a first case of mastocytosis with systemic involvement was described. From 1950, several different SM variants, including MCL, were reported. A first comprehensive proposal to classify mastocytosis had been worked out by the Kiel Group in 1979,19 and a similar classification was published by Dean Metcalfe in 1991.20

Between 1990 and 2000, the consensus group developed clinical, histologic, immunological, and biochemical markers of CM and SM. In the Year 2000 Working Conference on Mastocytosis, these parameters were discussed, and the most significant variables were selected as criteria to define mastocytosis and to differentiate variants of CM and SM.4 The resulting consensus proposal was adopted by the WHO and served as official WHO classification of mastocytosis in 2001 and 2008.5,6 In 2007, the consensus group refined the classification and proposed to define the smoldering state as a separate variant of SM.12 The following disease variants are well defined: (1) ISM; (2) smoldering SM (SSM); (3) SM with an associated hematologic non-MC-lineage disease (SM-AHNMD); (4) ASM; and (5) MCL (Table 1). The poor-prognosis variants of SM (SM-AHNMD, ASM, and MCL) are often referred to as advanced SM. During the past 15 years, the consensus group continued to work on criteria, markers, and standards and formulated diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms, as well as treatment response criteria.7,12,14,21

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic WHO criteria of CM and SM are generally accepted. CM is defined by typical features of cutaneous lesions, a “positive” skin histology, and absence of criteria sufficient to establish the diagnosis of SM.12,14 A positive Darier's sign (swelling and redness of skin on stroking) supports the conclusion that the patient is suffering from CM.12,14,22 However, identical cutaneous lesions are also seen in SM. Therefore, the lesion per se is described as “mastocytosis in the skin” (MIS; Table 1), and only a thorough BM examination can establish the final diagnosis: CM or SM.12,14 It is noteworthy that a minimal infiltration of the BM with neoplastic MCs may well be detected in CM. Even if two minor SM criteria (but no major SM criterion) are found in these patients, the diagnosis remains CM.4-6

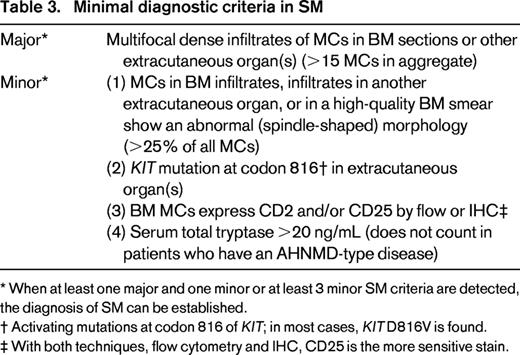

However, when at least one major and one minor SM criterion or at least three minor SM criteria are fulfilled, the diagnosis of SM is established (Table 3).4-6 The major SM criterion is a histologically confirmed multifocal infiltration of one or more extracutaneous (visceral) organ(s) by neoplastic MCs. The BM is most commonly affected in these patients. Therefore, BM biopsy material should be examined routinely in all cases with suspected SM.4-6 Recommended stains for detection and quantification of MCs (percentage infiltration) in the BM are KIT [cluster of differentiation (CD) 117], CD25, and MC tryptase.4,12,23 In patients with typical SM, smaller and larger compact infiltrates of spindle-shaped MCs are detectable in immunostained BM sections.23 Minor SM criteria include the following: (1) an atypical morphology of MCs (including typical, spindle-shaped MCs); (2) expression of CD2 or/and CD25 by MCs; (3) the presence of KIT D816V in the BM or another extracutaneous organ; and (4) a basal serum tryptase level exceeding 20 ng/mL (Table 3).4-6

Minimal diagnostic criteria in SM

* When at least one major and one minor or at least 3 minor SM criteria are detected, the diagnosis of SM can be established.

† Activating mutations at codon 816 of KIT; in most cases, KIT D816V is found.

‡ With both techniques, flow cytometry and IHC, CD25 is the more sensitive stain.

Remarkably, most patients with CM are children, whereas in adulthood, most patients are diagnosed with SM. Therefore, in childhood, no BM biopsy is required unless clear signs of advanced SM (eg, very high tryptase level of >100 ng/mL, marked cytopenia, lymphadenopathy, and/or splenomegaly) are found.12,14 In contrast, a BM biopsy is always recommended in adults to establish a correct diagnosis. In those who present with a typical rash but refuse a BM biopsy, the provisional diagnosis of MIS should be established, whereas the traditional way to diagnose CM in such cases should be avoided. With regard to diagnostic algorithms, assays, and standard procedures, we refer to the available literature.12,14,24,25 A simplified version of a diagnostic algorithm is shown in Figure 1. The most important screen parameter in suspected SM remains the basal serum tryptase.4,12

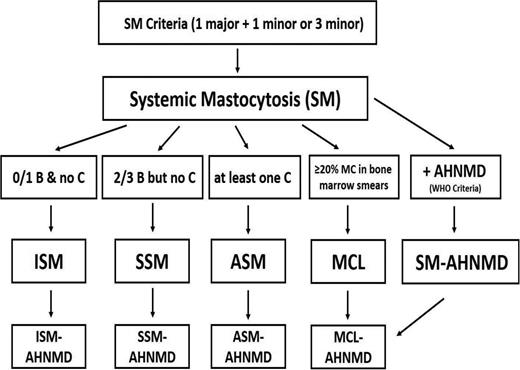

Diagnostic algorithm in SM. Based on the presence of at least one major and one minor or at least 3 minor SM criteria, the diagnosis of SM is established. Thereafter, the patient has to be examined for the presence of B findings, C findings, percentage of MCs in BM smears (to exclude the presence of MCL), and signs of an AHNMD. In patients with 0 or 1 B findings, no C findings, and no signs or symptoms indicating the presence of MCL or AHNMD, the final diagnosis is ISM. In those who present with 2 or 3 B findings but no C findings (and no MCL/AHNMD), the diagnosis of SSM is established. If at least one C finding is present, the diagnosis changes to ASM, and in those who also have at least 20% MCs in their BM smears, the diagnosis changes to MCL. In any variant of SM, an AHNMD may be diagnosed as a concomitant disease. In a final step, the AHNMD variant needs to be determined by WHO criteria.

Diagnostic algorithm in SM. Based on the presence of at least one major and one minor or at least 3 minor SM criteria, the diagnosis of SM is established. Thereafter, the patient has to be examined for the presence of B findings, C findings, percentage of MCs in BM smears (to exclude the presence of MCL), and signs of an AHNMD. In patients with 0 or 1 B findings, no C findings, and no signs or symptoms indicating the presence of MCL or AHNMD, the final diagnosis is ISM. In those who present with 2 or 3 B findings but no C findings (and no MCL/AHNMD), the diagnosis of SSM is established. If at least one C finding is present, the diagnosis changes to ASM, and in those who also have at least 20% MCs in their BM smears, the diagnosis changes to MCL. In any variant of SM, an AHNMD may be diagnosed as a concomitant disease. In a final step, the AHNMD variant needs to be determined by WHO criteria.

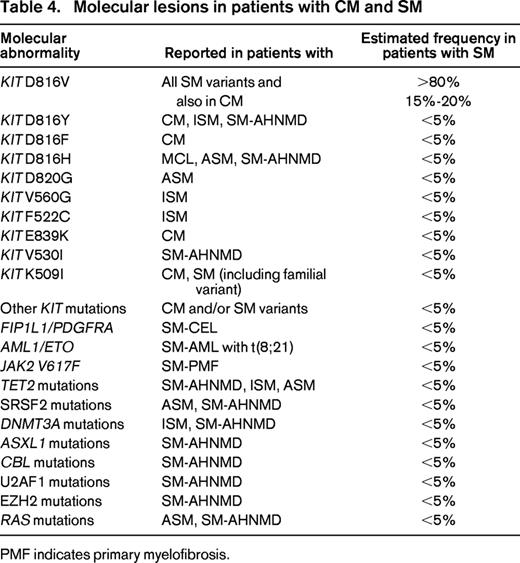

Molecular features and target antigens

The most commonly detected somatic lesions in patients with mastocytosis are activating KIT mutations that trigger autonomous growth and expansion of neoplastic MCs.24,26-28 In childhood CM, KIT mutations are found in ∼20%–40% of all cases.28 In these patients, a number of different codons of KIT, including 816, may be affected.26-28 In contrast, in a vast majority of all adult patients, the KIT mutation D816V is detectable in neoplastic cells, independent of the category of SM (Table 3).26,27 In fact, KIT D816V is also found in most ISM patients (>90%) known to have a normal life expectancy.27 This is remarkable and suggests that other (KIT-independent) factors are critically involved in disease progression. Indeed, a number of additional somatic mutations are found in patients with SM-AHNMD, ASM, and MCL. These lesions include, among others, mutations in TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, CBL, RUNX1, and RAS (Table 4).29-32 Such additional lesions may be coexpressed with KIT D816V in the same cells (same subclones) but may also be detectable in other myeloid lineages, especially in patients with SM-AHNMD. Based on colony assays, KIT D816V appears to be a late event in such patients.33 In general, the type and number of lesions (mutations) detectable in patients with multimutated SM correlates with prognosis, drug response, and survival.32 In many of these cases, important drug targets, such as pro-oncogenic kinases that may be responsive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), are detectable in neoplastic cells (Table 4).

In a majority of patients with AHNMD, a myeloid neoplasm is detected.4-6,12,34,35 In contrast, lymphoid AHNMDs (myelomas or lymphomas) are very rare. Among myeloid AHNMDs, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is commonly diagnosed.34,35 Other AHNMDs detectable in SM patients comprise acute myeloid leukemia (AML), JAK2-mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), or MPN/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) overlap disorders. In AHNMD patients, recurrent, disease-related, molecular lesions are often found (Table 4). Likewise, in SM-AML, RUNX1-ETO has been described as a recurrent fusion gene. In addition, patients with SM-CMML and SM-AML may display one or more karyotype abnormalities.35

A special condition is chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL) with FIP1L1-PDGFRA (F/P).29,34 Although an increase in clonal MCs is often seen in F/P-positive (F/P+) CEL, only a few patients fulfill criteria of SM (SM-CEL), because the SM component is usually small and neoplastic cells usually lack KIT D816V. The delineation between F/P+ CEL and KIT D816V+ advanced SM with eosinophilia (eg, ASM-eo) has important clinical implications. In particular, only those with typical CEL with rearranged PDGFR, but not those who have advanced SM-eo with KIT D816V, respond to imatinib. In a few patients with advanced SM, usually MCL, no KIT mutations are found. These cases have to be delineated distinctively from patients with myelomastocytic leukemia.36 In contrast to MCL, myelomastocytic leukemia does not fulfill SM criteria, and an underlying advanced myeloid neoplasm (advanced MDS or MPN, or an AML) with secondary MC involvement is found.36

Other differential diagnoses to MCL include basophilic leukemias and acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Diagnostic algorithm and staging in patients with SM

In adults with typical skin rash, it is standard to perform a full staging program, including a BM examination, independent of the tryptase level and other test results.12,25 In adults with suspected SM in whom no cutaneous lesions are found but typical mediator-related symptoms (eg, histamine symptoms or anaphylaxis to hymenoptera venom) are present, the serum tryptase level is a well-accepted screen parameter.12,25 In symptomatic patients with a clearly (and persistently) elevated basal serum tryptase, a BM is usually recommended. It is important to note that the tryptase level can transiently increase above the individual baseline during an anaphylactic event. Therefore, it is standard to assess basal tryptase levels at least 48 hours after resolution of all event-related symptoms.25 A novel, powerful screen parameter is KIT D816V in the PB. In particular, using a highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) approach, KIT D816V can be detected in PB leukocytes in >70% of all patients with SM, including those who have ISM.24 Therefore, this parameter can be used in patients with suspected SM in whom neither skin lesions nor a clearly elevated basal tryptase is found.24,25

Once diagnosed, several additional staging investigations have to be performed in SM. BM investigations include morphologic assessment of (Wright-Giemsa–stained) BM smears, histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC), cytogenetics, PCR (to detect KIT D816V), and multicolor flow cytometry if available.24,25,37 Flow cytometry should be performed to document expression of CD2 and CD25 on neoplastic MCs.37 Expression of CD2 and CD25 in BM MCs can also be demonstrated by IHC.38 With both methods (flow and IHC), CD25 appears to be a more sensitive (and thus recommended) stain. In addition to BM studies, a complete blood count with (microscopic) differential counts and blood chemistry, including serum tryptase, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, coagulation parameters, and total IgE levels, are determined at diagnosis.12,25 Finally, staging in SM includes osteodensitometry [T score by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan] and an abdomen ultrasound. In case of (suspected) advanced SM, bone x-ray studies should also be performed to exclude or document the presence of osteolyses.12 It is noteworthy that BM investigations are only recommended for adults with suspected SM, whereas in children, BM studies are usually not required, unless visible signs of a malignant disease process are detected.12

Variants and subvariants of SM

Based on organ involvement, MC burden, and SM-related organ damage, several different variants and subcategories of SM have been defined. ISM is defined by SM criteria and absence of criteria to diagnose SSM (<2 B findings), ASM (not a single C finding), MCL (MCs <20% in BM smears), and an AHNMD (Table 1; Figure 1).4-7 The BM smear usually contains <5% MCs, and no circulating MCs are found in the PB. In patients in whom a concomitant AHNMD is detectable, the diagnosis changes to SM-AHNMD (Table 1).4-7 A special subvariant of ISM is (isolated) BM mastocytosis (BMM; Table 1).4,12 In these patients, skin lesions are absent and the MC burden is low, often with a normal or near-normal basal tryptase. It is important to be aware of this rare ISM subvariant for several reasons. First, in many cases, the diagnosis is overlooked because of the absence of skin lesions (occult SM), which may be relevant for those who develop life-threatening anaphylaxis or bone fractures attributable to osteroporosis.12 Second, in SM patients without skin lesions, ASM and MCL are important differential diagnoses.1,4-6 A distinction between BM mastocytosis and ASM/MCL can be made by demonstrating a low serum tryptase level and absence of C findings.

In SSM, 2 or 3 B findings, but no C finding, are detectable (Figure 1; Table 1).4-6,12 The BM smear in SSM usually contains <5% MCs. The most important differential diagnosis to SSM is SM-AHNMD. In fact, in SSM patients, BM studies may show signs of dysplasia or/and myeloproliferation, but the diagnostic criteria for a myeloid AHNMD are not fulfilled.4-6 As soon as such criteria are fulfilled, the diagnosis changes from SSM to SM-AHNMD (Figure 1, Table 1).

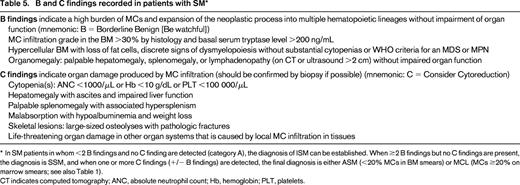

In patients with ASM, one or more C findings (SM-induced organ damage) are detectable, and the same holds true for most patients with (acute) MCL (Table 1).4-7 It is important to note that a C finding counts as SM-related organ damage only when caused by a local massive MC infiltration, which should be documented by biopsy whenever possible.4,7 B and C findings are shown in Table 5. Based on the numbers of MCs in BM smears, patients with ASM can be divided further into classical ASM (MCs <5%) and ASM in transformation (ASM-t; 5%–19% MCs in BM smears; Table 1).36,39 This delineation is of prognostic significance because the risk of full transformation to MCL in ASM-t is much higher than in classical ASM.39 In addition, the maturation stage of MCs correlates with prognosis.39

B and C findings recorded in patients with SM*

In SM patients in whom <2 B findings and no C finding are detected (category A), the diagnosis of ISM can be established. When ≥2 B findings but no C findings are present, the diagnosis is SSM, and when one or more C findings (+/− B findings) are detected, the final diagnosis is either ASM (<20% MCs in BM smears) or MCL (MCs ≥20% on marrow smears; see also Table 1).

CT indicates computed tomography; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelets.

In patients with MCL, the BM smear contains ≥20% MCs (of all nucleated BM cells; Figure 1, Table 1).4,7,36 In typical cases, MCs can be quite immature and may also be detected in the PB.36,39 However, in a majority of all patients with MCL, MCs account for <10% of leukocytes in PB smears.4,7,36,39 In these cases, it is appropriate to establish the diagnosis “aleukemic MCL” (Table 1). MCL may occur as a primary (de novo) disease but may also develop from ASM or SM-AHNMD.36

More recently, a delineation between chronic and acute MCL has been proposed.36 In chronic MCL, no C findings are detected, whereas in acute (classical) MCL, at least one C finding is present (Table 1).36 The prognosis in MCL is poor. Only a few patients with acute MCL survive >1 year, even when treated with chemotherapy, targeted drugs, or stem cell transplantation (SCT). The prognosis in chronic MCL may be slightly better, although after a variably latency period, progression from chronic to acute MCL may occur in most cases.

The most important differential diagnoses to MCL are myelomastocytic leukemia, basophilic leukemias, and acute promyelocytic leukemia.36

Management of CM and SM in the follow-up

In childhood patients with clinically silent CM, follow-up (FU) investigations should be performed once a year and include physical examination and laboratory parameters with blood counts and serum tryptase.12 In many cases, the disease resolves shortly before or during puberty. In adult patients with CM or stable ISM, a similar FU is recommended.12,22 In contrast to CM, the FU in ISM also includes osteodensitometry and sonographic spleen size measurements. The KIT D816V allele burden can also be measured in the FU but is not yet recommended as standard. In SM patients with suspected progression, a complete restaging, including BM studies, molecular studies, and a search for C findings, has to be performed; in those with advanced SM, more frequent FU examinations are usually required.12 In patients who have a decreased T score, a yearly DXA scan should be performed before and during therapy with bisphosphonates.12 During treatment with cytoreductive agents or targeted drugs, repeated BM examinations are required to document drug effects in advanced SM.7,12,21 In addition, various PB parameters, including differential counts (eosinophils), serum tryptase levels, the alkaline phosphatase level, and the KIT D816V allele burden (if the test is available), should be used to document drug responses. However, the most important question remains whether the drug is able to induce a partial or complete resolution of C findings.7,12,21

Treatment options in ISM

In asymptomatic patients with ISM and those who are suffering from mild symptoms, prophylactic therapy with histamine receptor (HR) blockers is recommended.1,4,12 Most patients with recurrent severe mediator-related symptoms respond to a combination of HR1 and HR2 antagonists (standard basic therapy). If this is not the case, additional drugs are prescribed, depending on the presence of comorbidities (eg, allergies) and organ systems involved.1,4,12 In case of severe GI symptoms, proton pump inhibitors are used in addition to (but never without) HR2 blockers.1,4,12 In those who are suffering from severe allergic reactions or even an MC activation syndrome with anaphylaxis, corticosteroids, or/and MC stabilizers may be required to keep the symptoms under control.4,12 Indeed, coexisting allergies (usually IgE-dependent) are a major challenge in patients with ISM. Because of the high risk of life-threatening anaphylaxis, these patients are advised to carry 2 or 3 epinephrine pen self-injectors and to use them after appropriate information and training, preferably in an allergy center. A special challenge is allergy against bee or wasp venom.10-14 These patients are at high risk to develop fatal anaphylaxis and therefore should undergo life-long immunotherapy.12,14 For refractory cases, antibody-mediated depletion of IgE and other experimental drugs have been considered. In a subset of patients with repeated life-threatening anaphylaxis, cladribine (2CdA) may work, especially when the MC burden is high, such as in SSM.40-42 In addition, it has been described that some of the novel TKIs, such as PKC412 (midostaurin), counteract IgE-dependent mediator secretion in MCs.43 Indeed, treatment with PKC412 may improve mediator-related symptoms in patients with SM.44

Another special challenge in ISM is osteopenia and osteoporosis, especially in women and those who are treated with (long-term) corticosteroids.12 When the T score drops to below −2, bisphosphonates should be prescribed.12 However, not all SM patients with galloping osteopenia or overt osteoporosis may respond. For these cases, experimental drugs, such as receptor activator of NF-κB ligand inhibitors or low-dose interferon-α (IFN-A) are recommended.

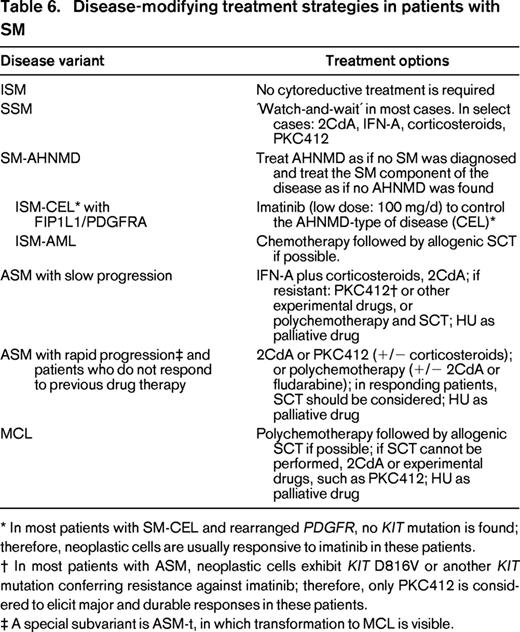

Treatment options for patients with SSM or advanced SM

In SSM patients who have no symptoms or signs of progression, no specific therapy is required. In case of mediator-related symptoms, treatment is identical to that in ISM. In SSM patients with severe anaphylaxis or signs of progression, 2CdA is often recommended and is usually effective in reducing the MC burden.40-42

In ASM patients with slow progression (no signs of transformation), IFN-A (as long-term subcutaneous therapy) or 2CdA (3-6 cycles) have been considered as first-line therapy.42 In fact, although no controlled clinical trials have been performed, several studies have shown that these drugs are able to reduce the MC burden and sometimes even revert C findings in patients with ASM.40-42 Response rates range from ∼10%-20% for IFN-A and 15%-30% for 2CdA. In patients with rapidly progressing ASM, ASM-t (MCs 5%-19% in BM smears), and acute MCL, more intensive therapy is required (Table 6).42 In young and fit patients, polychemotherapy containing fludarabine or 2CdA, often in combination with cytosine arabinoside (using regimens otherwise applied in refractory AML) may be used. In case of a measurable response, hematopoietic SCT should be considered.42 Notably, SCT has been described to induce continuous remission in a subset of patients with ASM and MCL.45 In older patients and those who cannot tolerate intensive therapy, conventional cytoreductive agents (2CdA) or palliative drugs [hydroxyurea (HU)] may be prescribed.42 A novel approach is to apply targeted drugs directed against KIT D816V in these patients (Table 6). Indeed, it has been described that PKC412 can induce major (and sometimes even durable) responses in a substantial subset of patients with ASM and MCL.44

Disease-modifying treatment strategies in patients with SM

* In most patients with SM-CEL and rearranged PDGFR, no KIT mutation is found; therefore, neoplastic cells are usually responsive to imatinib in these patients.

† In most patients with ASM, neoplastic cells exhibit KIT D816V or another KIT mutation conferring resistance against imatinib; therefore, only PKC412 is considered to elicit major and durable responses in these patients.

‡ A special subvariant is ASM-t, in which transformation to MCL is visible.

A special situation is SM-AHNMD. In these patients, both the SM component and the AHNMD component of the disease may need specific therapy. The prognosis in these patients is usually predefined by the AHNMD.4,34,35 A well-accepted standard is to treat the SM component of the disease as if no AHNMD was diagnosed and to treat the AHNMD component of disease as if no SM was found (Table 6) with recognition of potential drug interactions and side effects, and appreciation that any AHNMD must be regarded as secondary neoplasm and thus as a high-risk neoplasm.4,12,42 Likewise, in SM-AML, the AML component has to be regarded and treated as secondary AML. Some of these patients benefit from chemotherapy and subsequent SCT, even if the SM component cannot be eradicated completely.43 It is also noteworthy that, in most patients with so-called “AML with KIT D816V,” an occult SM is diagnosed when the BM is examined thoroughly. SM-CMML is the most frequent type of SM-AHNMD. In these cases, the CMML component is often resistant. Therefore, these patients are also potential candidates for intensive therapy or experimental drugs, such as 2CdA, demethylating agents, or PKC412.42 Another special variant of SM-AHNMD is SM-CEL with a rearranged PDGFR. In several of these patients, the F/P fusion gene product is detected.29 However, only a very few patients carry both KIT D816V and F/P. Therefore, these patients are usually responsive to low-dose imatinib (100 mg/d) in the same way as F/P+ CEL patients without SM. In contrast, in patients with ASM-eo or SM-AHNMD-eo exhibiting KIT D816V, imatinib (and other TKIs that spare KIT D816V) does not exert anti-neoplastic effects, because the KIT mutant introduces resistance. In some of the patients with SM-AHNMD, the AHNMD component may display JAK2 mutations or a JAK2 fusion gene product that is responsive to JAK2-targeting drugs. Moreover, several other drug targets have been identified recently in patients with SM-AHNMD.30-32 Therefore, it is of utmost importance to apply the full armamentarium of molecular markers in these patients.

In many cases with ASM, SM-AHNMD, or MCL, intensive therapy cannot be offered and applied because of age, poor performance status, or other factors. For these patients, palliative therapy is required. The standard of treatment for such patients is HU.42

In patients with MC sarcoma (MCS), the treatment plan is similar to that in MCL. In fact, most patients with MCS transform to MCL within weeks or months. In addition to chemotherapy, irradiation may be applied in an attempt to achieve “debulking” before SCT. However, despite intensive therapy, most patients with MCS die within a short time interval.

Summary and future perspectives

Mastocytosis is a rare hematologic disease defined by abnormal expansion and accumulation of clonal MCs in various tissues and organs. During the past few years, an overwhelming load of information concerning the pathogenesis, disease-related markers, and targets relevant to SM and its variants has been accumulated. Based on this development, it is important to diagnose and manage all patients using currently available standards and recommendations provided by the consensus group. In addition, it is of importance to manage and treat all patients with advanced SM in a multidisciplinary approach, preferably in a specialized center. Indeed, treatment of advanced SM remains a challenge in applied hematology. Whereas several of these cases respond to 2CdA or IFN-A, most patients relapse or have resistant disease. For these patients, polychemotherapy and novel experimental drugs, including TKIs directed against KIT or other kinase targets, can be prescribed or are available through compassionate use programs. For the future, there is hope that these and other novel agents will receive approval by healthy authorities and that their use will lead to a substantial improvement in survival and quality of life in these patients. For drug-resistant patients who have advanced SM and are young and fit, SCT remains an alternative treatment option.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund Projects SFB F4611 and SFB F4704-B20.

Correspondence

Prof Peter Valent, Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Hematology and Hemostaseology, and Ludwig Boltzmann Cluster Oncology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, Vienna, Austria. Phone: 43-1-40400-60850; Fax: 43-1-40400-40300; e-mail: peter.valent@meduniwien.ac.at.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has consulted for and received honoraria from Novartis.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: Treatment of advanced systemic mastocytosis: cladribine (2CdA), PKC412 (midostaurin), interferon-α.