Abstract

A 70-year-old male with a history of atrial fibrillation who is being anticoagulated with dabigatran etexilate presents to the emergency room with melena. He reports taking his most recent dose of dabigatran more than 2 hours ago. On examination, he is hypotensive and tachycardic, and he continues to have melanotic stools. Laboratory testing reveals a calculated creatinine clearance of 15 mL/min, a prothrombin time of 16.5 seconds (reference range: 11.8-15.2 seconds), an international normalized ratio of 1.2 (reference range: 0.9-1.2), and an activated partial thromboplastin time of 50 seconds (reference range: 22.2-33.0 seconds). You are asked by the emergency medicine physician whether hemodialysis should be considered to decrease the patient's plasma dabigatran level.

Learning Objective

To describe recommendations for or against the use of hemodialysis for dabigatran-associated major bleeding and the underlying evidence, based on a review

Discussion

Dabigatran etexilate, an oral prodrug of a direct thrombin inhibitor, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for risk reduction of stroke and embolism associated with atrial fibrillation (AF), as well as treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism.1 After absorption and conversion to its active form, dabigatran reversibly binds to thrombin's active site, preventing its conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Dabigatran's plasma concentration peaks within 1.5-2 hours of ingestion and decreases by >70% over 4-6 hours, with its terminal half-life being 12-17 hours with continued therapy. Dabigatran is primarily excreted through the kidneys (85%), with the remainder excreted in the bile.2

The RE-LY study revealed an increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding associated with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily versus warfarin among AF patients,3 which was corroborated in a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials also showing an increased risk of GI bleeding with dabigatran compared with vitamin K antagonists (relative risk = 1.51, 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.84).4 However, the recent FDA Mini-Sentinel analysis using health insurance claims and administrative data found that new users of dabigatran did not appear to have a higher, real-world incidence of GI or intracranial hemorrhage than those starting on warfarin.5 For major bleeding, an antidote against dabigatran is not yet available [although a dabigatran-specific antibody fragment (aDabi-Fab, idarucizumab)6 is currently being studied in humans]. Only low-quality evidence is available to support the use of hemostatic agents such as prothrombin complex concentrates.7-11 Gastric lavage or activated charcoal can reduce GI absorption only if the last dose of dabigatran was taken within 2 hours of the major hemorrhage.12

Because only 35% of dabigatran is protein bound, hemodialysis has been proposed as a possible treatment strategy in patients with dabigatran-associated major bleeding. Published reports have shown that 4 hours of hemodialysis can reduce the plasma concentration of dabigatran by 59%-68%,13,14 although drug levels can increase after intermittent dialysis sessions due to redistribution from extravascular compartments.15-18

To examine the current best evidence for the use of hemodialysis in dabigatran-associated major bleeding, we conducted a Medline search of articles published between January 2000 and July 2014. Keywords “dabigatran” (1979 hits), “hemodialysis” (56 hits), and “hemorrhage” or “bleeding” yielded 41 articles. Of these, 32 articles were excluded: 7 were non-English, 21 did not include original data, 1 was a survey, 1 did not involve hemodialysis, and 2 did not involve bleeding. Nine studies were included: 1 retrospective database review, 2 retrospective case series, and 6 retrospective case reports; there were no published prospective studies (Tables 1, 2).

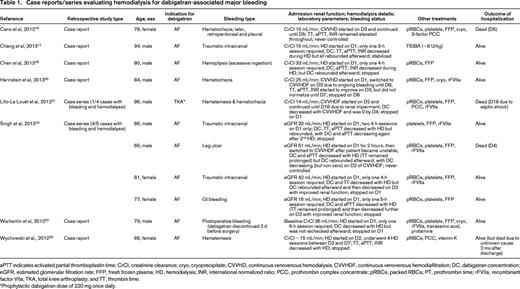

Case reports/series evaluating hemodialysis for dabigatran-associated major bleeding

aPTT indicates activated partial thromboplastin time; CrCl, creatinine clearance; cryo, cryoprecipitate; CVVHD, continuous venovenous hemodialysis; CVVHDF, continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration; DC, dabigatran concentration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; HD, hemodialysis; INR, international normalized ratio; PCC, prothrombin complex concentrate; pRBCs, packed RBCs; PT, prothrombin time; rFVIIa, recombinant factor VIIa; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; and TT, thrombin time.

*Prophylactic dabigatran dose of 220 mg once daily.

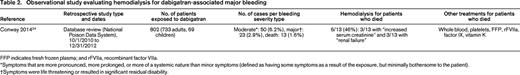

Observational study evaluating hemodialysis for dabigatran-associated major bleeding

FFP indicates fresh frozen plasma; and rFVIIa, recombinant factor VIIa.

*Symptoms that are more pronounced, more prolonged, or more of a systemic nature than minor symptoms (defined as having some symptoms as a result of the exposure, but minimally bothersome to the patient).

†Symptoms were life threatening or resulted in significant residual disability.

Among the 11 patients with dabigatran-associated bleeding treated with hemodialysis, all were ≥65 years of age, with 5 being >80 years and 1 being >90 years. All except 1 patient took dabigatran for AF. GI bleeding was present in 5, traumatic intracranial hemorrhage in 3, and the remaining 3 cases involved hemoptysis, cutaneous bleeding, and postoperative bleeding. The calculated creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate was decreased in all instances, with 7 involving intermittent hemodialysis only, 1 entailing intermittent hemodialysis followed by continuous hemodiafiltration, and the remaining 3 using continuous hemodialysis or hemodiafiltration. A rebound in dabigatran concentration was seen in 5 of 6 patients who had a follow-up level drawn after their initial hemodialysis session, although only 2 required additional hemodialysis. Adjunctive therapies such as blood products, prothrombin complex concentrates, and recombinant factor VIIa were used in all cases. Only 2 of the 11 cases resulted in death due to uncontrolled hemorrhage, both of which occurred despite continuous hemodialysis or hemodiafiltration.

In their database review of the National Poison Control System, Conway et al24 found a total of 802 patients with reported exposure to dabigatran over 2.25 years, 23 (2.9%) of whom suffered life-threatening or disabling bleeds and 13 (1.6%) of whom died. Among those who died, 6 of 13 (46%) underwent hemodialysis, all of whom had at least some degree of renal insufficiency.24

Based on the available data published in the literature, hemodialysis may be of some benefit in dabigatran patients with major bleeding. However, the risk of placing a large-caliber venous catheter and the time to arrange and perform hemodialysis must also be considered.16 In patients with normal renal function, the concentration of dabigatran will decrease quickly without hemodialysis and thus each case should be considered individually, taking into account the timing of the most recent dose of dabigatran, the patient's laboratory parameters (ie, renal function, dabigatran concentration, and/or coagulation tests), and the clinical course of the patient's hemorrhage. Clinical trials to evaluate antidotes against dabigatran should be pursued.

In a patient with serious (life-threatening) dabigatran-associated bleeding and a calculated creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min, we suggest that hemodialysis be performed if emergent hemodialysis is available and if appropriate vascular access can be obtained (grade 2C).

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.K. has consulted for Novo Nordisk, CSL Behring, Bayer, and Baxter. D.A.G. has consulted for Daiichi-Sankyo, Janssen, Pfizer, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and CSL Behring. Off-label drug use: recombinant factor VIIa and prothrombin complex concentrates for reversal of dabigatran.

Correspondence

Benjamin Kim, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Ave., M1286, Box 1270, San Francisco, CA 94143-1270; Phone: (415)514-6354; Fax: (415)476-0624; e-mail: bkim003@gmail.com.