Abstract

Preparing a career development award can be an immensely satisfying experience and a great boost to a research career if successful, or it can seem like a miserable waste of time if unsuccessful. This paper highlights tips for the preparation of patient-oriented career development awards and provides references for grant-writing guidance. Patient-oriented research is defined as “research conducted with human subjects (or on material of human origin such as tissues, specimens and cognitive phenomena) for which an investigator directly interacts with human subjects. This area of research includes: 1) mechanisms of human disease; 2) therapeutic interventions; 3) clinical trials, and; 4) the development of new technologies.”1

Introduction

Why should junior investigators devote the extraordinary time and effort required to write and submit research grants? For young investigators, the 3 to 5 years of salary and “protected time” provided by most career development awards is critical if you want to establish a successful academic research career. Few investigators are ready and able to compete for independent research faculty positions right after their fellowship or postdoctoral training. Being awarded a career development award also provides external validation of your potential to contribute meaningful knowledge as a researcher, and having a career development award on your curriculum vitae is helpful when you apply for jobs. Of the 2784 K08 and K23 grant awardees from 1997 to 2003, 42.5% of awardees successfully competed for an R01 award in the subsequent 10 years.2 On a practical level for physician scientists, a career development award may allow you to “buy time” from other income-producing duties such as attending on the wards or seeing patients in clinic so that you can focus on your research project.

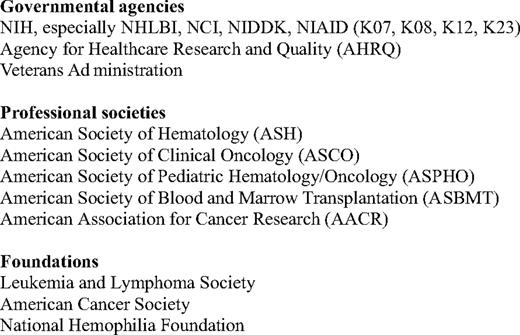

There are many funding sources for clinical career development awards. (Table 1) The primary National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding mechanisms for mentored hematology research are the K awards (K07, K08, K12, and K23), which are supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Not all of the institutes support all of the award types, and levels of funding and other requirements vary, so be sure to check. Other governmental funding sources include the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Veterans Administration (VA). Professional societies such as American Society of Hematology (ASH), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (ASPHO) and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) sponsor career development awards, as do foundations such as the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF). The overall success rate of applicants to these funding sources ranges from less than 10% to 45%. For example, in 2009 the K23 success rate was approximately 50% for NHLBI, 31% for the NCI, 44% for NIDDK, and 53% for NIAID. These were much better than the rates in 2007, which were 26%, 16%, 38%, and 43%, respectively.3 Over the last several years, the ASH scholar awards success rate has been approximately 18%, similar between first- and second-time applicants (Elisa Shea, personal communication).

If you are a member of a historically disadvantaged group (e.g., for racial, ethnic, disability, educational, or financial reasons) or work in an underrepresented area of research (e.g., aging), then there may be special grant opportunities available to you. Speak to your program officer early to identify these funding mechanisms.

'Ready'

This overview assumes that the applicant has already performed the necessary groundwork to develop an appropriate clinical research project. Optimally, there is at least a draft of the protocol so that the inclusion/exclusion criteria, end points, and biostatistics have been defined. The project should not only be important science, but also should provide you with the opportunities to develop the research skills you will need to be a successful independent investigator. I am also assuming that you and your mentor(s) have discussed possible funding sources, and that submitting a grant now fits into a broader career development plan.

'Get Set'

Although it is exciting to get started, I recommend that you first accomplish three dull tasks that will help your grant writing effort be more successful.

First, obtain the grant application instructions and read them all carefully. For NIH, this includes both the program announcement or the funding opportunity announcement (FOA)1 and the application guide.4 This ensures that you are aware of all the requirements, that no eligibility criteria have changed rendering you now ineligible, and that there are no early deadlines, such as a letter of intent. It is important to read the page limits, the font and margin requirements, and the required components of each section, and to keep these in mind as you are crafting your grant application. Also be aware of any items that will take extra time to collect, for example unusual letters or attestations. Make a list of all items required for grant submission and create a detailed timeline. If you simply write “prepare grant” on your to-do list, you will focus on the more fun and seemingly important task of writing the research strategy, but will be left scrambling to assemble all of the other information that allows the grant to be submitted. Review your detailed timeline with experienced grant writers and with your grant administration specialist to be sure that the list is comprehensive and the timeline realistic. On your list, indicate what you need to do yourself and where you'll need others' help. For those tasks where you will rely on others, let them know early and allow ample time for them to complete their tasks. Busy people travel a lot, have their own deadlines, and sometimes go on extended vacations or sabbaticals.

Second, read and understand the five review criteria for the research project for NIH grants: significance, approach, innovation, investigators, and environment. Also be familiar with the five NIH review criteria for career development awards: candidate, career development plan, research plan, mentor/consultant/collaborator, and environment and institutional commitment to the candidate. Although these review criteria vary by funding source, they are a good general guideline. Make a list of the positive things you'd like your reviewers to list under these sections and post them somewhere where you can glance at them. For example: “Significance: high impact project, clear clinical relevance, will generate widely generalizable data.” Be honest and as specific as you can be. It is important to accentuate the strengths and mitigate the weaknesses of you and your project.

Third, obtain examples of other successfully funded similar grants from your friends and colleagues. If possible, obtain any “pink sheets,” the written feedback from the study section review. Copies of supporting documents are also very helpful (letters of support, budget justifications) if your friends feel comfortable sharing them with you, which they usually are once they are funded themselves. Reading through someone else's grant helps to get you in the right frame of mind and can give you helpful suggestions in preparing your own application. Reading pink sheets helps you see how the grant application gets reviewed and what reviewers think is important.

'Go!'

“A grant application is not science; it is the marketing of science. Clarity is the key to any successful marketing strategy. It is therefore imperative to write clearly.” –Ferrara5

Research Strategy

I am assuming that your research project is already developed. Therefore, the goal of the research plan is to demonstrate to your reviewers and to the rest of the study section that your study question is important, your approach reasonable, and that you are a careful, competent investigator with the training, resources, and perseverance to achieve your specific aims.

Many outstanding review articles are available in the grant writing literature6–10 and prior ASH grant educational sessions5,11,12 that summarize tips for preparing the research plan. If you have not prepared a grant before, then you will probably find them very helpful. They provide explicit suggestions for approaching each section, as well as empiric data about the most common reviewer criticisms. I refer you to those rather than repeating them here. Instead, I will emphasize particularly important tips and focus on additional personal comments (Table 2).

Specific Aims

The specific aims section should be written first and will likely be revised many times as the application is prepared. Do not try to cram too much detail into this section or you will overwhelm your reviewers. You want to provide them with the broad picture of your research and its importance and relevance. What problem are you studying? In what population? Why does this research need to be done? If you are funded and everything goes according to plan, what will be the benefit to others (and you)?

Background and Preliminary Data

You use this section to educate the reviewers so that they understand what is already known relevant to the project and what you in particular have contributed to this knowledge. The preliminary data section can also be used to demonstrate feasibility of planned research methods, for example, by describing a relevant pilot study.

Study Design

The difficulty here is balancing page limits with the wealth of information that you could present about your project. Some details are mandatory for clinical applications, including inclusion and exclusion criteria; end points; measurement tools; and a detailed biostatistical section that addresses power calculations, sample sizes, missing data, and an overview of analytic plans and statistical approaches. Involvement of a biostatistician in writing or reviewing this section is critical because statistical flaws can rapidly become “fatal.” Acknowledge your statistician's input in the grant, and somewhere explain, perhaps in the career development section, how you will get ongoing statistical guidance.

Attention to quality control is important. How will you monitor the integrity of your study in an ongoing way? What are the processes to obtain complete and accurate data? How will you be sure that the intervention is actually delivered correctly? These details are important to reviewers and indicate attention to detail and the ability of the principal investigator not only to come up with the great ideas, but also to carefully supervise the research so that the study is interpretable in the end.

A “pitfalls and potential solutions” or “strengths and weaknesses” section is one of those things that reviewers look for and will note if absent. If this section is well written, it can turn recognized weaknesses into strengths by demonstrating investigator insight and creative problem solving. Be forthright about pitfalls. A table format can work well and save some space.

A timeline is a useful graphic that provides a (realistic) depiction of how everything fits into the allotted support period. Be sure to avoid saying that recruitment will take 4 years if the funding period is only for 3 years.

Optional Research Plan Section

If there is space, I like to include a “design rationale” section. Use this section to briefly discuss why you chose your study design over other possible approaches. It gives you an opportunity to explain, for example, why you are using a sequential design instead of a randomized trial, or why you chose one instrument over another. The content of this section can be guided by comments you've received from internal reviewers. Expect that there are other reasonable approaches to address your scientific question, and use this section as a sort of preemptive rebuttal to those comments. Needless to say, the language in this section should be respectful of alternative approaches.

Abstract

I write my abstract toward the end of the process, once I have worked through all of the other sections and can write a concise summary. However, don't leave the abstract until the very end, because it is often the first and only communication you have with the entire study section. Make sure that the language is unique and not just cut-and-pasted from somewhere else in your application. It will certainly incorporate concepts presented elsewhere in the grant, but some reviewers get annoyed by repetition.

“As in most human relationships, first impressions are very important. Thus, the Abstract and Specific Aims sections are generally important areas that each reviewer reads very carefully.” –Miller12

Internal Reviewers

After you and your mentor(s) are happy with a draft of your research plan, you'll want to have it reviewed internally by several people. Your ideal internal reviewers are those who: have the correct phenotype (are or could be reviewers of career development awards), have the correct expertise (are knowledgeable about your field or your methods), will engage (read your grant critically and provide high-level feedback), are punctual (will provide timely feedback so you have time to revise your grant), and care about you and your career. Ask in advance if they are willing to review, and confirm that your timetable works for them. Ideally, you would send the grant to them about 4 to 6 weeks before submission and give them 1 to 2 weeks to finish their review. Before sending your draft research plan to internal reviewers, read it out loud to yourself and correct all typographical and grammatical errors. Make sure of internal consistency (numbering of sections, figures, and tables). You don't want to distract your precious internal reviewers from the science by making them focus on the presentation.

Use the time when others are reviewing your grant to take a break from it and work on some of the other required elements. When you get reviews back, pull out the grant and read it again with fresh eyes. I treat these internal grant reviews as I do journal reviews. If it is a reasonable question or comment, consider addressing the issue preemptively in your grant.

Candidate Information

This section includes the candidate background, career goals and objectives, and career development/training activities during the award period. Because it is highly individualized to your background, interests, and goals, I only offer general suggestions. You may want to emphasize a theme (if one exists) between your clinical training and research pursuits. It is helpful if you use your prior experiences to illustrate what you learned, where you want to go, and how the career development award will help you get there. If you plan to take classes or get additional specialized training, make sure you include enough details about the training opportunities and justification of why these experiences will benefit you. Make sure everything is consistent throughout the grant and letters. Reviewers tend to focus on inconsistencies.

The Care and Feeding of Your Reviewers

“Writing with the reviewers in mind can be summarized to one simple concept: Do not make the reviewers work harder than they have to. Reviewers are busy people, with lives and careers outside of reviewing grants.” –Chung10

Without great science and a worthy candidate, it's very unlikely that a grant application will be funded just based on the window dressing. However, given fairly equal science, better scores will probably go to the better-written proposal. Reviewers acknowledge giving extra credit for clarity of thought, an appealing presentation (white space, graphics, straightforward language and flow), and the applicant's excitement about the project. These touches will communicate that you like and respect your reviewers, want them to understand what you are saying, and care what they think of you. You want reviewers to relax while reading your grant and conclude that your grant is “well written.” You definitely do not want them feeling annoyed.

Furthermore, a well-written and thoughtfully presented grant shows that you are a careful investigator who puts time and effort into the end product. Someone who lets his or her work out in public poorly thought through with typos and grammatical errors may be a brilliant scientist, but reviewers may question whether this person has the personal characteristics necessary for success.

Other Important Sections

On your list of application-specific tasks will be seemingly mundane items such as obtaining letters (from mentor, co-mentor, three to five references, institutional officials, consultants, and collaborators), ethics training, budget justification, resources page, human subjects section, targeted enrollment table, and cover letter. These sections should not be left until the end. If done in a leisurely manner as a break from the core research and career development plan, they can be relaxing. If left until the end, they can add up to a crisis.

Letters are painful to request and manage, so just plunge in and take care of them early. First, you want to be respectful of others' time. Second, you may need to provide drafts for some writers, so spreading out the task for yourself can decrease the pain. Some letters have very specific components with the required topics listed in the application instructions. For example, institutional letters from division and department heads outline the role of the applicant in the organization and discuss specific resources and promises made to the applicant. They should emphasize that your position and support is “position and support ARE guaranteed …” guaranteed regardless of the outcome of this application. Mentor letters need to include very detailed career development plans that must be consistent throughout the application. How often will the applicant and mentor meet, what topics will they discuss? How will the applicant transition to independence? The mentor letter can also discuss any extenuating circumstances forthrightly rather than hoping that reviewers will not notice a period of decreased productivity or a change of institution. Most experienced letter writers have a template that they modify for the applicant, but it doesn't hurt to print out and give your letter writers a current copy of the letter requirements so they remember all the components. Finally, provide addresses, self-addressed stamped envelopes, and other information necessary to make it easy for them to submit their letters.

Handling Rejection

If you are not successful, give yourself time and space to absorb the comments and go through the grieving process. Just like when a journal rejects your paper, use the critiques to make the application better by critically evaluating the comments, discussing them with your mentor and others and addressing them in the next submission. Then get back out there again and reapply. Once you are funded, no one asks and few know whether you were successful on your first or second try. However, since only two attempts are allowed now at NIH (in contrast to past years when three tries were allowed), and most other funding bodies only accept applications once a year, you may need to actually collect more data, perform a pilot, or otherwise take some time to make your grant better and fundable on the next round.

Good luck!

Disclosure

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Stephanie J. Lee, M.D., M.P.H., Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D5-290, Seattle, WA 98109, sjlee@fhcrc.org