Abstract

Written primarily for first-time applicants, this overview is a collection of tips intended to convey an approach to grant writing based on the experience of the author. Therefore, it is not a comprehensive review and it does not supplant the numerous treatises on grant writing, which cover everything from writing style and grammar to details regarding individual granting mechanisms and agencies. Rather, it is a brief overview of the grant writing process from conception to submission.

Introduction

Aut viam inveniam aut faciam. (“Either I shall find a way, or I shall make one.”)

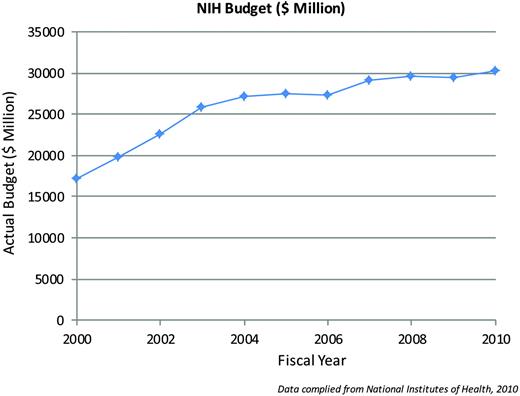

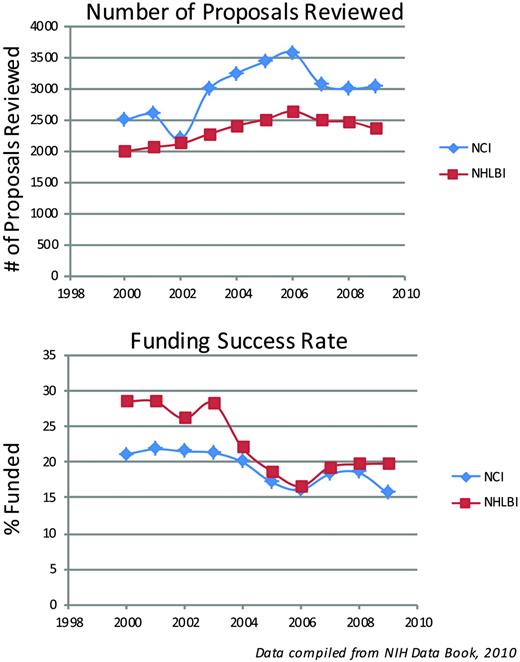

First, the bad news. It is difficult to write a good grant. It is uncommon to write a funded grant. The latest figures from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest source of funding for basic and translational research in the United States, bear the details of this observation. The NIH budget (Figure 1) doubled between 1999 and 2003, and since then the budget has remained relatively flat (or has fallen if adjusted for inflation), while the number of applications for funding has increased, reaching an all-time high of 47,500 in 2007. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) supplied an additional $10.4 billion in 2009 that was added to the 2009 and 2010 budgets, which, in addition to funding new grant mechanisms, also helped to maintain the pay line across the 27 NIH institutes and centers. Of relevance to ASH members are the number of reviewed grants and funding success rates for the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (Figure 2), which showed a flat or declining success rate of 15% to 20% in 2009. Although not depicted, similar figures are reported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). However, with the expiration of ARRA funds, the NIH has projected that it will fund only 35,202 grants in 2011, which is a drop of 4377. Complicating the funding picture for the next few years is the uncertainty about how many investigators who received the one-time ARRA grants will apply for new awards and how many of the 19,000 investigators who didn't receive ARRA grants will apply for new NIH Research Project Grants (RO1s).1

So, given this grim situation, one might ask “why should I apply for a grant?” After all, the average age for RO1-funded investigators has steadily increased to around 45 since 1980, adding to the worries of first-time applicants, who tend to be in their 30's. Nevertheless, I assume that because you are reading this you have already made it past the point of futility and that you have a good scientific question, that you have received strong laboratory training, and, most importantly, that you have a burning desire to do science. To increase your odds of being funding, then, it is even more important to prepare the strongest possible grant application. There is no secret for how to do this. There are no magic recipes nor guarantees, and no easy way out. Instead, we must apply some common-sense rules of grant preparation to overcome the realities of uncommon funding.

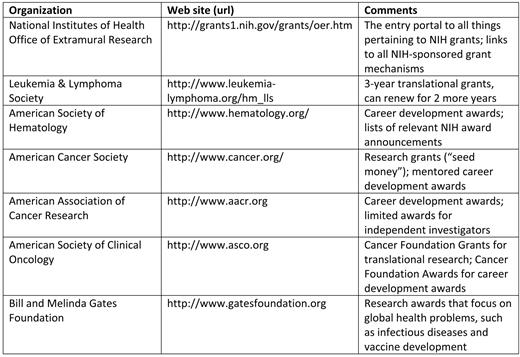

While the short segments that follow apply most specifically to RO1 applications, by far the most common mechanism for funding basic and translational research, there are additional sources of research grant support that have a similar peer-review process and use applications that share many of the same features of an NIH grant (Table 1). A winning strategy for success often includes submitting proposals to more than one of these organizations (and others not included in the table). If you avoid scientific and budget overlap in each of the proposals, you could be funded by more than one mechanism. In such a case, you will need to contact the institute program official at NIH and the extramural funding official at your own institution to discuss potential overlap. The mechanics of NIH grant submission and the details of preparing the actual proposal are covered in great detail by the NIH itself,2 so they will not be duplicated here.

Planning Your First RO1 Submission

Forming Your Hypothesis

Perhaps the most important element in successful grant writing is the same thing that drives the best science: asking a good question. In many ways, this is also the most challenging aspect of the grant process, because it involves inspiration, insight, imagination, and even invention (the “four I's”). From this single question, a hypothesis should logically follow and should be constructed based upon your preliminary data supplemented with—and supported by—the scientific literature. History is full of examples of truly great scientists who asked profound questions and who bravely pursued hypotheses that were often based on a single crucial observation. For example, there is Metchnikoff's observation of the phagocytes that accumulated after a thorn was placed into a sea urchin, which lead to the discovery that phagocytes that engulfed debris were common cells throughout the animal kingdom. Curiously, if he had made the observation today, he likely would have had insufficient preliminary data to submit a proper RO1, but you get the point.

Especially critical for first-time RO1 applicants is that your hypothesis be direct and stated as simply as possible, although not any simpler, to paraphrase Albert Einstein. Your hypothesis should be in the form of: “Given observations A and B, we hypothesize that if X occurs (or is true), then we will observe Y.” A very good hypothesis is one that, when tested, yields an interesting outcome even if the hypothesis is proven wrong by the results of the experiments. Avoid testing the null hypothesis where possible. You must be intellectually honest in your proposal and leave enough room for the possibility that you could be wrong. This frankness will unlock many opportunities to pursue alternative approaches that will become a necessary part of your proposal. Spend time writing about how you would pursue alternative outcomes and how this would alter your hypotheses. An inability or unwillingness to adequately develop alternative hypotheses and strategies is a common mistake for new applicants, but this problem can just as easily be avoided. Addressing these issues can become one of your proposal's greatest strengths.

Constructing Your Research Plan

Next come the specific aims of the project, the part where you actually discuss what you're planning to do with the money you will get. These should follow logically from your hypothesis. This is why it is critical that your hypothesis be directly testable. Although most investigators often propose two to four specific aims, it is more critical for first-time applicants to be focused and to keep the number of aims to a minimum (two or three at most), because your study section reviewers will consider that early-stage investigators need more time to accomplish the same amount of work, and you don't want to appear to be too ambitious in your research plan. Pay particular attention to the italicized text in this paragraph, because it highlights some of the most common areas for criticism of first-time RO1 applicants.

It is important that you show that you have accumulated an early track record of conducting relevant (and hopefully even important) research in your field. This is not as critical for early career development awards, but it is critical for a successful RO1 because you need to accumulate your own preliminary data upon which you build your hypothesis. Therefore, it is wise to have a few publications before you submit the proposal, and these ought to be as first- or last-authored publications. This demonstrates that you: a) actually have worked in the field you're investigating, b) you have produced your own preliminary data (and therefore you have shown some independence, even if the work was performed while you were in a mentor's laboratory), and c) you are well-versed in the techniques in your proposal and are capable of performing the experiments you propose.

During the early stages of preparing your proposal, it is a good idea to become familiar with research projects related to your work that have already been funded. You should search the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool (RePORT)3 (which replaced the Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects, or CRISP database), where you can read the abstracts of the currently funded NIH grants. In addition to giving you an idea about what your study section currently considers to be exciting work, you can use the information to compare your level of preparedness to that of other first-time awardees doing similar work. For example, you can decide how your own publication history, the scope of your proposal, and the number of collaborators compares with similar investigators who are already funded.

While at the NIH website, you should become familiar with the Requests for Proposals (RFPs) and Program Announcements (PAs), which are priority areas for NIH funding. You might find that your work falls within the scope of one of these funding announcements, or that by modifying an aim or two, you could be eligible to apply under an RFP. To help in this process, it is strongly encouraged that you discuss your planned proposal with an NIH program official at the institute that most closely fits with your proposal and would therefore be most likely to provide eventual funding.

Now you can prepare a detailed outline of your proposal—not the full, 12-page proposal, but four to six pages that comprise the main body. Include a paragraph or so each on your preliminary data, hypothesis, specific aims, alternative hypotheses and approaches, and a statement about the relevance of your work to the field and why it is so critical to solving the problem you are addressing. Just because your reviewers are scientists in the same or a related field, don't assume that they will automatically infer the significance of your proposal.

Asking for Help

Collaborators

Ask two or three experienced investigators at your institution (or collaborators) for advice about your proposal. It is most helpful to review your proposal in person so that you can interact and ask questions. An experienced investigator will be someone who has a long record of NIH funding and who might have served on a study section, and hopefully someone in your field or a closely related one. Check your ego at the door and ask them the hard questions. Did I ask an important and relevant question? Do I have a testable hypothesis? Do you consider the proposal to be novel? Did I include adequate methods and alternative approaches? Can I do this in less than 5 years? Based on these critiques, you should revise your draft application. It can be reassuring to see some examples of successfully funded recent applications, and they might be willing to share some with you.

You might need help from other investigators to carry out your project. This is because the best science is often done in collaboration, and as a first-time applicant you will likely not have all of the necessary expertise within your own laboratory. Collaborators are important for the success of any grant proposal, but this is especially true for first-time RO1 applicants. Identify areas of your proposal that need or would benefit from additional expertise. Collaborators can also provide formal guidance on conducting certain experiments and on aiding interpretation of your results, and you shouldn't be afraid to seek this level of collaboration. In addition, seek collaborations with investigators who can perform ancillary experimental assays or provide reagents or patient material. Remember that you will need letters of support from each of your collaborators, so provide them with your curriculum vitae, the abstract, and the specific aims of the grant well before the submission deadline. You should also provide collaborators with a draft letter that includes the specific role that they will play in your work (assays, reagents, patient material, or even scientific guidance and advice).

Statisticians

At this stage, you should meet with a statistician to discuss the necessary statistical methods, and consider whether he or she should be included as a collaborator on the project. This is important and should not be left to the end, when you might be rushing to get the application submitted.

Institutional Review Board Approval

If the application is translational and involves patients or patient material, prior to submission you will need to have a research protocol that has been approved by your institutional review board (IRB) to collect patient samples to support your work, to conduct a clinical trial, or both. You should have an already approved and open protocol, although at minimum it ought to be under consideration by your IRB prior to submission. This serves two purposes: 1) it demonstrates immediate availability of material and patients for your research, and 2) it shows your level of commitment to completing the project. In addition, early consideration must be given to requirements for Investigational New Drug applications (INDs) or for obtaining novel reagents (from other investigators, NIH, the Food and Drug Administration, or industry). The strongest applications are the ones demonstrating that all of the necessary documents have been completed and all of the necessary reagents are at hand at the time of submission.

The Writing Process

Once you have developed and critiqued the outline and considered the points above, now you should write the full proposal. Then re-write it. Then set it aside for a few days to a week. Then re-read it, re-write it, and repeat. Be careful to follow all of the instructions for completing the proposal. It is critical that each section of your proposal is consistent: if you proposed three specific aims in the abstract, then your research plan section ought to contain three aims using the same wording. In particular, stay within the limits on length for each section of the grant and use the proper font size. Grammar, syntax, and spelling are very important. Many institutions offer services to review grant proposals for proper grammar, and it's a good idea to take advantage of this. Once you have what you think is a complete draft, ask one or two experienced (i.e., good funding track record) investigators to read the proposal and offer their critiques. Again, ask them to keep the gloves off here because you want to have their honest opinions.

Budget

Regarding the budget of your proposal, you are the most qualified person to judge the costs of the work. Nevertheless, you may not be familiar with the cost of patient-related services, outside reagents, core facility services, and other budget items. Therefore, you should ask an experienced administrator or budget analyst at your institution to go over your entire application, including the budget, to help you with areas where you might be unfamiliar. Keep in mind that you might need to consult with administrators in patient care areas and you must budget the necessary time for this. Be careful not to cram in too much just before submission.

Submission and Resubmission

Finally, once you know the outcome of your grant review and you have the summary statement that includes the comments from the reviewers on your study section, you may need to prepare a resubmission. It happens to all of us. Remember that to be a scientist you must have thick skin in order to endure countless editors and reviewers, and to be a successful scientist you must give adequate consideration of that criticism, incorporate it, and carry on. Some of the criticisms and advice you receive from study section members may be way off scientifically, but you should take it all to heart because many of the observations and criticisms may be valid. Most importantly, you need to convince them in your resubmission that you have adequately addressed their concerns.

Above all, be tenacious, willingly self-critical, and persistent and you will ultimately be successful. Aut viam inveniam aut faciam.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing interests.

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Jeffrey J. Molldrem, MD, Professor of Medicine, Department of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Division of Cancer Medicine, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd., Unit 900, Houston, TX 77030; Phone: (713) 563-3334; Fax: (713) 563-3364; e-mail: jmolldre@mdanderson.org