Abstract

An Ara-C-containing intensified induction therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is considered a highly effective treatment strategy in younger mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients, inducing long-lasting remissions. However, ASCT is also hampered by acute and delayed toxicity. Thus, alternative first-line treatment strategies without ASCT but including novel agents are under investigation. With the recently published results of the TRIANGLE trial, showing superiority of an ibrutinib-containing immunochemotherapy induction followed by ASCT compared with the standard therapy and, more strikingly, a noninferiority of an ibrutinib-containing regimen without ASCT compared with the standard regimen with ASCT, we consider the addition of ibrutinib to first-line therapy in younger MCL patients as a new standard of care. Whether ASCT, with additional toxicity, still adds benefit to ibrutinib-based treatment in subsets of patients is not yet determined. In addition, it remains unclear how effective Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) therapy will be in the relapsed setting for patients who received BTKi as part of first-line therapy. It also remains unclear whether the TRIANGLE data can be extrapolated to other BTKi, which is particularly relevant considering it is no longer FDA approved for MCL. Until then, individual patient characteristics and preferences, disease biology, and estimation of risk of toxicity needs to be taken into account when deciding about the addition of ASCT to an ibrutinib-containing induction therapy. For patients with TP53 aberrations, ASCT should not be recommended due to potential toxicity and limited efficacy in this high-risk subgroup. Large randomized clinical trials such as ECOG-ACRIN 4151 will help to ultimately clarify the role of ASCT.

Learning Objectives

Acknowledge the different biological risk groups of mantle cell lymphoma

Evaluate the impact of dose intensification (ASCT) in mantle cell lymphoma

Estimate the benefit of targeted therapy (including BTKi and antibodies) in induction and maintenance

CLINICAL CASE

A 59-year-old woman presented with an incidental finding of an increased white blood cell count of approximately 20 G/l. Hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal. Cytomorphology of peripheral blood revealed 65% partially atypical lymphocytes, and flow cytometry showed a B-cell population expressing CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79b, and FMC7, while CD5, CD23, and CD10 were negative. Immunohistochemistry of a bone marrow biopsy revealed a 5% infiltration of the bone marrow by a classic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) with expression of CD20 and cyclin D1. CD23 was negative. Ki67 could not be determined in the bone marrow sample. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed an IGH::CCND1 rearrangement. A TP53 mutation or 17p deletion could not be detected. A positron emission tomographic scan revealed ubiquitous fluorodeoxyglucose-avid lymphadenopathy and hepatic infiltration. Consistent with the increased white blood cell count, the clinical Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score was defined as intermediate risk. An important question in the clinical management of this patient is whether consolidation with high-dose therapy and ASCT should be offered.

Discussion

In young and fit patients (≤65 years), a dose-intensified concept containing an immunochemotherapy induction followed by a high-dose consolidation regimen and ASCT constitutes the current standard of care.1,2 In a large randomized phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network (MCL Younger), the administration of the rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP)/dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP) regimen compared with administration of R-CHOP alone prior to myeloablative consolidation with ASCT more than doubled time-to-treatment failure (109 vs 47 months).2 A large randomized trial proved that consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by ASCT in first remission significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) (3.3 vs 1.5 years) and overall survival (OS).3 The value of high-dose immunochemotherapy followed by ASCT was also reported in the 15-year update of the Nordic MCL2 study after a median follow-up of 11.4 years: in this study, treatment of patients <66 years with alternating courses of R-maxi-CHOP (dose-intensified rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and high-dose cytarabine (HIDAC) followed by ASCT consolidation lead to a median OS and PFS of 12.7 and 8.5 years, respectively.4 Achieving prolonged duration of initial response is of great importance, taking into account that remission duration as induced by further treatment lines is generally shorter. This phenomenon was also observed in a pooled analysis (n = 370) in patients with relapsed MCL treated with the Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) ibrutinib evaluating the depth and durability of response depending on the number of prior lines: superior objective response rate (1 prior line 77.8% vs >1 prior line 66.8%), complete response (CR) rate (1 prior line 36.4% vs >1 prior line 22.9%), median PFS (1 prior line 25.4 months vs >1 prior line 10.3 months), and median OS (1 prior line not reached vs >1 prior line 22.5 months) was observed when patients were treated with ibrutinib at first relapse compared with treatment at later relapse.5

Furthermore, evolution of MCL biology over time impacts pathogenesis and aggressiveness.6 MCL is known to have one of the highest levels of genomic instability among lymphoid neoplasms.7 Whole-exome sequencing of 25 MCL patients at diagnosis and first relapse after the failure of standard immunochemotherapy revealed a significantly increased mean count of mutations per patient at relapse (n = 34) compared with diagnosis (n = 27).8 In another study, whole-exome sequencing of 33 longitudinally collected samples from 16 patients showed drastic clonal evolution in 11 of these samples that was associated with inferior survival.9 Regarding this, a long-lasting first remission should be the primary goal in treatment of MCL, and an intensified induction treatment followed by ASCT has proven to effectively achieve this.

However, it is important to note that this long-term efficacy of ASCT in MCL was established in the pre-rituximab era. The relative importance of ASCT vs no consolidation has not been prospectively evaluated in a randomized trial including modern induction therapy containing both Ara-C and rituximab. A critical question that needs to be discussed is also whether the PFS and OS benefit described with ASCT would nowadays be reached regarding the availability of better salvage therapies, targeted treatments, and optimized maintenance protocols. In a real-world analysis, retrospective data from 4,216 patients with MCL in the Flatiron Health electronic record–derived deidentified database diagnosed between 2011 and 2021, mostly in US community oncology settings, treatment outcomes and roles of ASCT and maintenance with rituximab in patients with previously untreated MCL were evaluated.10 There was no significant association between ASCT and real-world time to next treatment (hazard ratio [HR] 0.84; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.03; P = 0.10) or OS (HR 0.86; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.18; P = 0.4) among ASCT-eligible patients (n = 1265). In contrast, the addition of rituximab maintenance to immunochemotherapy (rituximab-bendamustine) resulted in a longer real-world time to next treatment (HR 1.96; 95% CI, 1.61 to 2.38; P < 0.001) and OS (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.92; P < .001).10 These findings may hint that long-term failure-free survival (FFS) and OS benefit in the first-line setting might be more likely impacted by improved maintenance therapy rather than ASCT. Rituximab maintenance after ASCT is currently considered standard of care for younger patients with MCL based on the results of a large phase 3 trial showing a significantly improved PFS (83% vs 64% after 4 years) and OS (89% vs 80% after 4 years) after 3 years of rituximab maintenance compared with observation only.11

Based on growing evidence of the strong prognostic potential of MRD status predicting improved subsequent PFS for MRD-negative patients at the end of induction and before high-dose consolidation,2 the currently ongoing randomized phase 3 trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (ECOG-ACRIN 4151; NCT03267433) aims to compare ASCT followed by maintenance rituximab with maintenance rituximab alone (without ASCT) in MCL patients in minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative first CR, irrespective of induction regimen. This study may pave the way for an MRD-guided treatment strategy with optional de-escalation of therapy in MRD-negative patients.

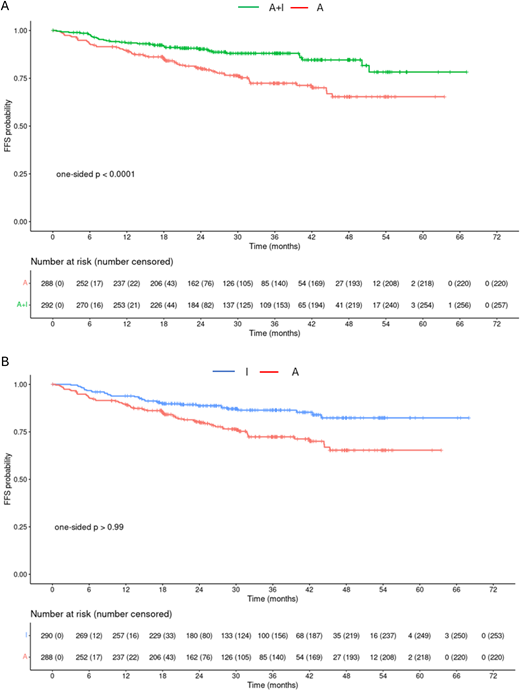

However, ASCT is also hampered by high acute and delayed toxicity. Thus, alternative first-line treatment strategies without ASCT but including novel agents are under investigation. This is particularly important when considering that the median age at diagnosis for MCL is 67 years; therefore, many MCL patients will be at increased risk for toxicity with ASCT. Recently, the phase 3 TRIANGLE trial12 evaluated the remaining value of ASCT for first-line therapy: 870 patients <65 years were treated with either the current standard of care including ASCT (arm A), the additional application of ibrutinib (arm A+I), or an ibrutinib combination without ASCT (arm I). After 31 months, the median follow-up, A + I was superior to A, with a 3-year FFS of 88% (95% CI 84%-92%) vs 72% (95% CI 67%-79%, one-sided p = 0.0008, HR = 0.52, one-sided 98.3% CI 0-0.86) (Figure 1A). Superiority of A over I was not shown, with a 3-year FFS of 72% (95% CI 67%-79%) vs 86% (95% CI 82%-91%, one-sided p = 0.9979, HR = 1.77, one-sided 98.3% CI 0-3.76) (Figure 1). The 3-year cumulative incidence of treatment failure was 21.9% (A, 95% CI 16.3%-27.5%), 6% (A+I, 95% CI 3%-9%), and 10.8% (I, 95% CI 6.9%-14.8%). OS at 3 years was 86% in arm A (95% CI 82%-91%), 91% in arm A + I (95% CI 88%-95%), and 92% in arm I (95% CI 88%-95%), but this is not statistically significant. To determine whether ASCT adds any benefit to the ibrutinib-only arm, longer follow-up is needed.

Failure-free survival (FFS) in months from randomization for A + I vs A (A) and A vs I (B).12

Failure-free survival (FFS) in months from randomization for A + I vs A (A) and A vs I (B).12

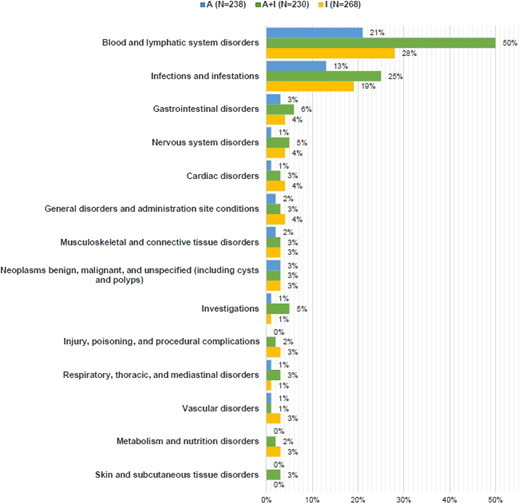

The TRIANGLE trial allowed rituximab maintenance added to all 3 trial arms according to national guidelines. As confirmed in an exploratory analysis, the addition of rituximab to maintenance therapy improved DOR in arm I (HR 0.35). However, observed toxicity rates, particularly cytopenias and infections, were higher when combining maintenance therapy, especially when patients received additional high-dose therapy, with 31% (arm A+I) and 25% (arm I) of patients developing at least 1 grade 3 to 5 adverse event (AE), whereas 15% (arm A+I) and 11% (arm I) of patients with ibrutinib maintenance only developed at least 1 grade 3 to 5 AE (Figure 2). In summary, the TRIANGLE trial demonstrated increased efficacy when adding ibrutinib to the previous standard approach with ASCT consolidation and shows nonsuperiority of the standard treatment over an ibrutinib- containing induction regimen without ASCT. As such, it defines a new standard of care in frontline treatment of young and fit MCL patients. Whether ASCT, with additional toxicity, still adds benefit to ibrutinib-based treatment in a subset of patients is not yet determined. We consider the results of this trial practice-changing. Nevertheless, follow-up is still short, and one might argue that noninferiority of arm I vs A regarding 3-year FFS might be achieved by ibrutinib maintenance. Importantly, the ibrutinib maintenance in the TRIANGLE trial was applied for a fixed duration of 2 years, and the majority of patients were still in remission after completing maintenance. Thus, reexposition to a BTKi in the relapse setting may be a valuable option. However, limited data on a BTKi-rechallenge after a time-limited ibrutinib treatment are available in MCL. It is important to note that it is possible that outcomes after relapse may be affected by previous BTKi exposure during induction and maintenance with lower responses to salvage BTKi.

Frequency of patients with at least 1 grade 3-5 AE by system organ class (occurred in at least 3% of patients in any treatment group) by treatment during maintenance/follow-up.12

Frequency of patients with at least 1 grade 3-5 AE by system organ class (occurred in at least 3% of patients in any treatment group) by treatment during maintenance/follow-up.12

MCL is a very heterogenous disease, and high-risk disease characteristics have been defined as high p53 expression and Ki-67 > 30%, together with blastoid morphology, which have been associated with a significantly shorter FFS and OS.13 Despite optimal immunochemotherapy, high-dose cytarabine, and ASCT, younger patients with MCL with deletions or mutations of TP53 have an unfavorable prognosis, as reported in the European MCL Younger Trial14,15 and confirmed in the Nordic MCL2 and MCL3 trials.16 In the latter, TP53 mutations, del17p, NOTCH1, and CDKN2A mutations as well as high MIPI-c, blastoid morphology, and Ki-67 > 30% were associated with inferior survival. However, in a multivariate analysis, only TP53 mutations retained prognostic impact for OS (median 1.8 vs 12.7 years). Accordingly, the new lymphoma classification systems now recommend to determine Ki-67 proliferation index and TP53 status mandatory at first diagnosis.17,18 As a strong correlation between p53 protein expression and TP53 missense mutations was observed,19 immunohistochemical quantification of p53 may be considered a valid prognostic surrogate if TP53 sequencing is not available. Due to increased toxicity and no confirmed benefit of high-dose immunochemotherapy and ASCT in the high-risk group of patients with TP53 aberrations, these patients should not be consolidated with ASCT. In contrast, these patients especially benefit from addition of ibrutinib standard to first-line treatment. It is an open question whether earlier application of immunotherapeutic approaches such as CAR T cells or T-cell engagers may at least partially overcome the negative prognostic impact of TP53 alterations in these patients.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

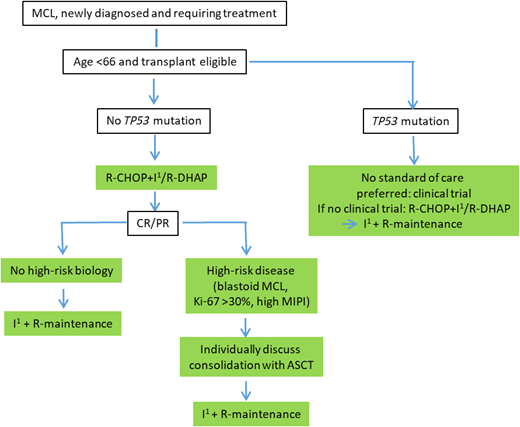

We return to our 59-year-old-patient with classic MCL, intermediate MIPI, and no TP53 aberration. According to our recommended treatment algorithm as depicted in Figure 3, the patient received an ibrutinib-containing induction treatment as applied in arm I of the TRIANGLE treatment without ASCT consolidation. End of induction staging revealed complete remission. The patient is now on maintenance treatment with ibrutinib and rituximab.

Conclusion

An Ara-C-containing intensified induction therapy followed by ASCT remains a highly effective treatment strategy in younger MCL patients, inducing long-lasting remissions. However, no randomized trial has shown an OS benefit with ASCT when modern rituximab-based regimens are used. With the recently published results of the TRIANGLE trial showing superiority of an ibrutinib-containing immunochemotherapy induction followed by ASCT compared with the standard therapy and, more strikingly, a noninferiority of an ibrutinib-containing regimen without ASCT compared with the standard regimen with ASCT, we consider the addition of ibrutinib to first-line CHOP-like therapy and rituximab maintenance in younger MCL patients a new standard of care. It is tempting to speculate that second- generation BTKi adds to chemotherapy in a similar fashion with a more favorable toxicity profile. However, phase 3 data are lacking. Whether ASCT, with additional toxicity, still adds benefit to ibrutinib-based treatment in subsets of patients is not yet determined. Until then, individual patient characteristics and preferences, disease biology, and estimation of toxicity risk need to be taken into account when deciding about the addition of ASCT to an ibrutinib-containing induction therapy. For patients with TP53 aberrations, ASCT should not be recommended due to potential toxicity and limited efficacy in this high-risk subgroup. These patients should, whenever possible, be treated within clinical trials. A recommended treatment algorithm depending on high-risk biology is depicted in Figure 3. Large randomized clinical trials such as ECOG-ACRIN 4151 will help to ultimately clarify the role of ASCT.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

E. Silkenstedt: no competing financial interests to declare.

M. Dreyling: research report: AbbVie, Bayer, BMS/Celgene, Gilead/ Kite, Janssen, Lilly, Roche; speaker's honoraria: AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Gilead/Kite, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Roche; scientific advisory board: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS/Celgene, Gilead/Kite, Janssen, Lilly/Loxo, Novartis, Roche.

Off-label drug use

E. Silkenstedt: nothing to disclose.

M. Dreyling: nothing to disclose.