Learning Objectives

Review the major updates in the 2023 American College of Rheumatology and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria for APS

Understand the distinction between classification criteria used for research purposes versus clinical care

CLINICAL CASE

A 43-year-old woman is evaluated for thrombocytopenia, with a nadir platelet count of 50 × 109/L. Three months prior, she was found to have mitral valve thickening on an echocardiogram performed for shortness of breath. A lupus anticoagulant is persistently positive at baseline and 12 weeks later. An alternative etiology for thrombocytopenia is not identified. Does this patient meet classification criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome?

2023 American College of Rheumatology and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an acquired systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by macrovascular arterial or venous thrombosis, pregnancy morbidity, microvascular phenomena, and other nonthrombotic manifestations in the context of compatible laboratory testing for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). An APS diagnosis may be challenging to make, as patients present with a wide variety of clinical manifestations, and aPL laboratory testing requires standardized techniques and nuanced interpretation. An APS diagnosis may have considerable treatment implications, such as initiation of vitamin K antagonist therapy for thrombotic APS or low-molecular-weight heparin and aspirin for obstetric APS. Given the diverse spectrum of features in patients with suspected APS, the Sapporo classification criteria (originally published in 19991 and revised in 20062) helped to establish clear clinical and laboratory definitions in this disease. The aPLs included in these criteria are the lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin IgG and IgM, and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM.

However, with advancements in our understanding of APS pathophysiology and recognition of diverse clinical phenotypes, it became clear that updated APS criteria were needed. In 2023, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) put forth revised APS classification criteria, with notable differences from the revised Sapporo defitions.3

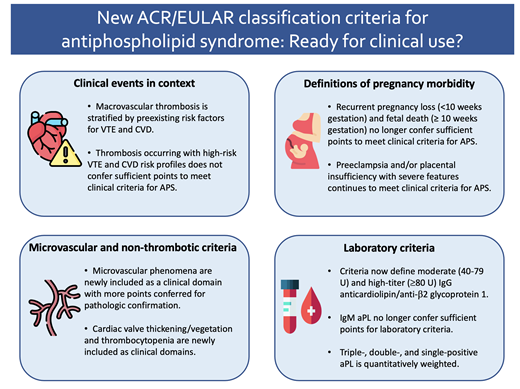

The ACR/EULAR criteria were designed to capture a highly specific patient population using an additive, weighted scoring system in 6 clinical and 2 laboratory domains to facilitate research in well-defined, homogeneous cohorts. Particular emphasis was placed on the context in which clinical events occurred, subphenotypes within obstetric morbidity, microvascular and nonthrombotic disease manifestations, and distinctions between aPL profiles. Patients can be considered for the new classification criteria if they have a positive aPL test within 3 years of a disease-defining clinical event. To subsequently meet classification for APS, patients must attain at least 3 points from 1 or more clinical domains and at least 3 points from 1 or more laboratory domains (Table 1).

Although designed for research purposes, the revised Sapporo classification criteria have been used to guide clinical practice for the past 25 years. We anticipate the 2023 ACR/EULAR classification criteria, which were expressly created to harmonize research and not for APS diagnosis, may be utilized in a similar fashion. In this review, we highlight key changes proposed in the ACR/EULAR criteria and examine how these changes may potentially inform diagnosis of APS and management in the clinical setting.

Clinical events in context

The revised Sapporo classification criteria made no distinction between a thrombotic event due to clearly defined risk factors versus unexplained thrombosis, with both fulfilling clinical criteria for APS. On the contrary, in the ACR/EULAR criteria, an arterial thrombosis in the context of a high-risk cardiovascular disease (CVD) profile and a venous thromboembolic event (VTE) in the context of a high-risk VTE profile do not meet the clinical criteria score required for APS. For instance, a patient with a deep venous thrombosis sustained after major surgery who also has persistently positive aPLs would only accrue 1 of 3 required clinical points. A patient with stroke and positive aPLs, but with strong CVD risk factors, would only obtain 2 of 3 required clinical points. The goal of this change is to capture a homogenous group of patients with positive aPLs and otherwise unprovoked thrombotic events, more likely attributed to APS.

High-risk CVD and VTE profiles and true APS are not mutually exclusive, however, and a high-risk profile does not preclude the development of future APS-qualifying clinical events. In fact, multiple risks often occur simultaneously in the same patient and may be additive.4 In a multicenter cohort analysis of 185 patients initially meeting revised Sapporo criteria for APS,5 90/185 patients (48.7%) no longer satisfied the required composite score by ACR/EULAR criteria. The percentage of patients classified with APS decreased from 47.3% to 34.9% most commonly due to high-risk CVD or VTE profiles and early pregnancy loss. Notably, over one-third (32/90) of these patients later developed clinical events to fulfill ACR/EULAR classification, all of whom had previously fulfilled ACR/EULAR laboratory criteria when they were first included in the cohort. This observation suggests that clinicans should maintain a high index of suspicion for APS in patients who do not meet strict ACR/EULAR classification criteria but who otherwise exhibit characteristics of this disease.

Expanded definitions of pregnancy morbidity

In a major change from the revised Sapporo criteria, the ACR/EULAR classification now assigns different relative weights to individual criteria within the larger domain of pregnancy morbidity. While preeclampsia (PrE) and placental insufficiency (PI) with severe features each continue to meet ACR/EULAR clinical criteria for APS, recurrent pregnancy loss (<10 weeks gestation; RPL) and fetal death (≥ 10 weeks gestation; without PrE/PI) were deprioritized in the ACR/EULAR criteria to confer only 1 point each (Table 1). It is important to recognize that RPL/fetal death were deprioritized not necessarily due to a conclusive lack of association between RPL/fetal death with APS in the existing literature but rather due to the heterogeneity of the observations and the limitations of the preexisting retrospective methodology, such as insufficient evaluation of other causes for fetal death, lack of confirmatory aPL testing, and inclusion of patients with low-titer aPL.6 In the aforementioned cohort analysis,5 the percentage of patients with pregnancy morbidity meeting criteria for APS based on the modified Sapporo criteria decreased from 26.9% to 3.2% when classified by ACR/EULAR. Notably, this group comprised the majority of patients who later developed clinical events meeting ACR/EULAR criteria, suggesting that aPL positivity in patients with RPL or fetal death may still predict future APS-qualifying clinical events. Shared decision-making and clinical expertise in reproductive hematology are paramount in these challenging clinical situations.

Microvascular complications and nonthrombotic criteria

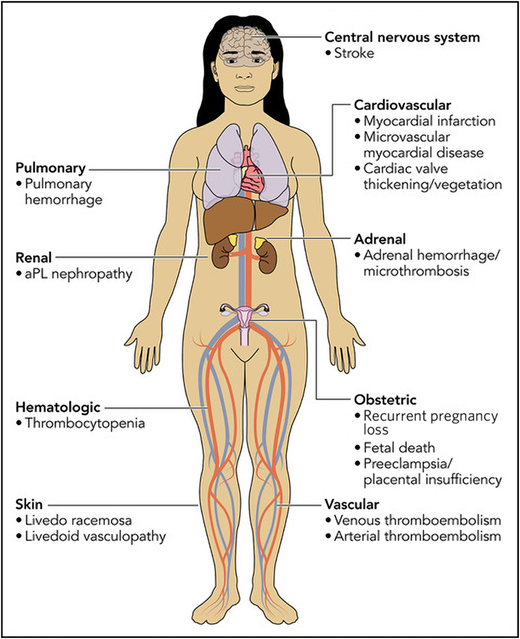

In a major change from the revised Sapporo classification, the ACR/EULAR criteria now assign points for clinical domains beyond macrovascular thrombosis and obstetric complications. Microvascular manifestations (such as livedoid vasculopathy, aPL-nephropathy, pulmonary hemorrhage, and myocardial disease) previously represented a less commonly recognized manifestation of APS and are newly represented in their own clinical domain (Figure 1 and Table 1). A score of 5 points is given to microvascular complications established by pathologic examination in contrast to only 2 points for microvascular complications diagnosed on clinical suspicion alone. (The exceptions are pulmonary hemorrhage and myocardial disease, which may accrue a full 5 points based on results of bronchoalveolar lavage and diagnostic imaging, respectively.) In addition, cardiac valve thickening or vegetation and thrombocytopenia are also formally included in their own clinical domains (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome included in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria. For detailed definitions of the clinical criteria and documentation, readers are referred to Table 1 of the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria document.

Clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome included in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria. For detailed definitions of the clinical criteria and documentation, readers are referred to Table 1 of the 2023 ACR/EULAR APS classification criteria document.

Similar to traditional criteria, these clinical features should be unexplained by other susceptibility factors, and clinicians should not confer points if there are equally or more likely etiologies. A full review of alternative etiologies is available in Supplementary Section 4 of the ACR/EULAR criteria.3 Microvascular manifestations of APS have a distinct pathophysiology from that of macrovascular thrombosis, and management of microvascular and hematologic manifestations typically requires approaches beyond anticoagulation, such as immunomodulatory agents (eg, glucocorticoids and B-cell depletion).7 Overall, we expect that the explicit inclusion of these new clinical domains will improve recognition and appropriate management of APS tailored to unique aspects of this disease.

Updated laboratory criteria

The major changes in ACR/EULAR laboratory criteria include precise definitions for moderate (40-79 U) and high-titer (≥80 U) IgG anticardiolipin/anti-β2-glycoprotein-I as measured by solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA); the deprioritization of isolated moderate-higher titer IgM anticardiolipin/anti-β2-glycoprotein-I; and quantitative weighting of triple positive, double positive, and single positive aPLs.8 The significance of an isolated IgM aPL should be interpreted with caution; while existing literature is mixed regarding the prognostic role of IgM aPL, it is generally accepted that IgG aPL is more strongly associated with thrombosis.9 However, clinical correlation is strongly advised as some studies have observed a substantial prevalence and even prognostic utility of IgM aPL, particularly in older adults with stroke10 and potentially obstetric APS.11 The ACR/EULAR criteria also confer more points as the greater the absolute number of positive aPLs increases, underscoring the significant risk of subsequent thrombosis in patients with triple positive APS versus other antibody profiles.12

It is also worth noting that anticardiolipin/anti-β2- glycoprotein-I antibodies are increasingly being detected with non-ELISA assays, such as large, automated platforms that use different immunoassay systems (ie, chemiluminescence). Further studies are needed to correlate and incorporate results of the most validated and accessible testing modalities into future classification criteria in order to maintain clinical relevance and homogenous participant recruitment for research.

Practical considerations for the ACR/EULAR classification criteria

We recognize that it may be difficult to apply complex classification criteria designed for research purposes in the clinical setting, and below we summarize 2 practical considerations.

Patients not meeting classification criteria may still have APS

The ACR/EULAR criteria were validated in 2 international cohorts of patients referred for evaluation of APS and yielded an improved specificity for diagnosis of 99%, compared with 86% using the revised Sapporo criteria. However, sensitivity dropped to 84% in the ACR/EULAR criteria compared with 99% with the revised Sapporo criteria. Thus, clinicians must not prematurely eliminate the possibility of APS in patients who do not meet strict classification by ACR/EULAR but who otherwise exhibit characteristics supportive of APS. Real-world examples may include patients with IgM anticardiolipin antibodies and recurrent thrombosis despite anticoagulation with non–vitamin K antagonists, or patients with positive aPLs and microvascular thrombosis not verified by pathologic examination. Clinical judgement is always paramount when deciding upon APS- directed therapy.

Diverse clinical manifestations should be recognized but properly attributed to APS

The new domains captured in the ACR/EULAR classification criteria highlight the diverse clinical manifestations of APS. And while some data may already be available during an initial patient consultation (such as platelet count), other more specific testing, such as echocardiograms (to assess cardiac valve disease) or abdominal imaging (for adrenal hemorrhage), is unlikely to to have been performed in the absence of a specific indication for testing. While we encourage comprehensive histories, reviews of systems, and physical exams, further research is needed regarding the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of evaluating patients for all potential manifestations of APS in the absence of symptoms or other clinical indications to do so.

Should clinicians identify a potential clinical manifestation of APS, we encourage comprehensive evaluation to exonerate other etiologies. For instance, in a patient presenting with positive aPLs and thrombocytopenia, we recommend a comprehensive evaluation for alternative reasons for a low platelet count given how commonly thrombocytopenia is observed in the general population. Similarly, cardiac valve disease should not be attributed to other causes, and microvascular manifestations should be carefully evaluated for other etiologies specific to the affected organ system.

Conclusions and future directions

While the 2023 ACR/EULAR classification criteria have resulted in more specific and homogenous patient populations for research in APS, they do not replace clinical judgment when caring for this diverse group of patients. Moving forward, prospective studies should prioritize questions such as thromboprophylaxis in patients with positive aPLs not meeting clinical criteria for APS; the use or selection of immunomodulatory therapy for microvascular or nonthrombotic manifestations; identification of patients for whom direct oral anticoagulant therapy may be appropriate; and management of patients with obstetric APS with poor outcomes despite traditional therapy. Additional areas for exploration in the translational realm might include validation of unique autoantibodies and biomarkers of endothelial or vascular damage; incorporation of cell-surface based complement assays into clinical care; refinement of existing aPL assays; and application of molecular and genomic profiling to further characterize this group of patients. Such advances will shed further light on the pathogenesis and natural history of this disease, ultimately paving the way to a more personalized approach to APS care.

Recommendations

Diagnosis of APS should include patients with cardiac valve and hematologic disease manifestations (Grade 1B).

Clinical events ascribed to APS must be examined in context and not be attributed to other more common etiologies (Grade 1B).

APS should still be considered in patients who do not meet strict classification by ACR/EULAR criteria but in whom there is otherwise strong clinical suspicion for APS (Grade 1C).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Andrew B. Song: no competing financial interests to declare.

Rebecca K. Leaf has received consulting fees from Alnylam Pharma and Recordati Pharma and has received grant support from Disc Medicine.

Off-label drug use

Andrew B. Song: None to disclose.

Rebecca K. Leaf: None to disclose.