Key Points

Ex vivo stored platelet-rich plasma undergoes profound changes once transfused into an in vivo environment regardless of storage temperature.

Cold-stored platelets aggregate more at the site of injury, whereas room-temperature platelets cause more fibrin formation.

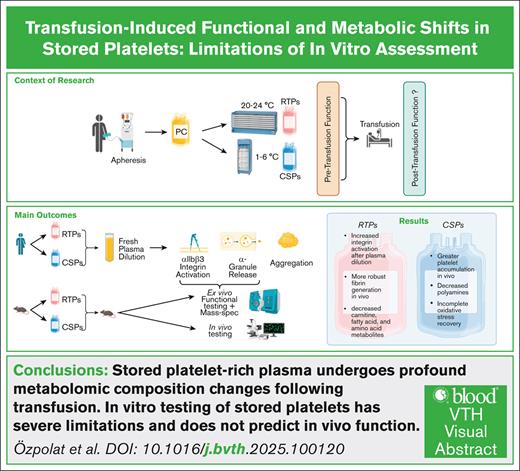

Visual Abstract

The impact of the stored platelet extracellular environment on function and the ability of platelets to change their function upon transfer into in vivo environments remain poorly understood. Human platelets were stored ex vivo at 20°C to 24°C (room temperature–stored platelets [RTPs]) or 1°C to 6°C (cold-stored platelets [CSPs]) and tested for function in the concomitant storage plasma or fresh plasma. In mice, we tested platelet function after ex vivo storage in concomitant plasma and after transfusion to mice ex vivo and in vivo. We also investigated stored platelet-rich plasma before and after transfusion to mice for metabolomics by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. In in vitro, human RTPs showed a greater ability than CSPs to improve αIIbβ3 integrin activation upon dilution with fresh frozen plasma. Mouse RTPs’ in vitro integrin activation improved more than that for CSPs after transfusion. Surprisingly, in mice, CSPs facilitated significantly greater platelet accumulation than RTPs in vivo. In contrast, fibrin generation was significantly more robust in RTPs than in CSPs during the early stages of hemostasis. In mouse RTPs, more metabolites changed significantly upon transfusion than in mouse CSPs. Transfusion decreased carnitine species, fatty acid metabolites, and amino acids only in RTPs, whereas polyamines decreased only in CSPs. The recovery from storage-induced oxidative stress was more complete in RTPs than in CSPs. Our findings highlight the severe limitations of in vitro testing of stored platelets. Platelet-rich plasma undergoes profound changes in metabolomic composition following transfusion. We further demonstrate the ability of platelets to undergo marked changes upon transfusion in RTPs more so than CSPs.

Introduction

Platelet transfusions are integral to the care of bleeding patients and as prophylaxis to prevent bleeding. Shortages resulting from the limited shelf life of room temperature–stored platelets (RTPs, up to 7 days) and bacterial mitigation requirements have increased the urgency for developing alternative platelet transfusion products. Although conventional RTPs have prolonged circulation time after transfusion, their storage lesion is severe, with poststorage characterization revealing a proinflammatory and hypofunctional in vitro phenotype.1-3 Nevertheless, RTPs are the most widely used US Food and Drug Administration–approved platelet product, supported by randomized controlled trial data showing some evidence of function.4-7

Cold-stored platelets (CSPs) are one of the most promising alternative platelet transfusion products based on in vitro function. Compared with RTPs, they show advantageous function with prolonged storage in a wide range of assays.8-11 The clearance rate of CSPs is significantly increased,12-14 but it is unclear whether this matters clinically when immediate hemostasis is needed.15-17 With CSPs, both human and mouse storage experiments have suggested platelets are primed for activation but may also be primed to undergo substantial phenotypic changes with rewarming to 37°C and exposure to physiological shear.9,18-22 These changes are partly mediated by increased von Willebrand factor platelet binding and glycoprotein (GP) Ibα-mediated signaling, gearing platelets toward a more prothrombotic phenotype. For example, the immediate changes after transfusion involve body temperature, blood flow, and altered extracellular environment. These are currently not captured with standard poststorage in vitro platelet function testing.

In vitro testing of stored platelets is commonly conducted to predict in vivo quality and clinical outcomes.23 It is usually performed in the concomitant stored extracellular environment, which is known to differ substantially between platelet storage products and is not representative of posttransfusion physiological (in vivo) conditions.24,25

In contrast to the scant platelet literature on this subject, numerous articles on the important role of posttransfusion in vivo rejuvenation of red blood cells exist.26 Clarifying the possible presence and magnitude of transfused platelet change of function is critical to prioritizing the experiments to evaluate platelet transfusion products. Efforts should be focused on preventing irreversible changes, such as those that are not changed upon transfusion. In this initial exploration of the possible presence and magnitude of transfused platelet functional changes from the poststorage milieu, we investigate the role of the extracellular environment in both RTPs and CSPs in vitro and in vivo. To characterize the potential in vivo change of function, we utilized different mouse transfusion and state-of-the-art metabolomic models.

Study design and methods

Apheresis platelet collection and storage

We collected platelets by apheresis using the Trima Accel Automated Blood Collection System (Terumo BCT, Denver, CO) and stored them in anticoagulant-citrate-dextrose solution A and plasma. The target platelet yield was 3 × 1011/unit to 4.5 × 1011/unit, depending on the donor’s baseline platelet count and the target concentration of ∼1500 × 103/μL. Each unit had platelet concentrations and volumes within acceptable bag parameters. CSPs were stored without agitation at 1°C to 6°C. Following standard practices, RTPs were stored at 20°C to 24°C with agitation.13,27 Platelets were stored for 7 days, and functional testing samples were collected on days 3 and 7 (Figure 1A).

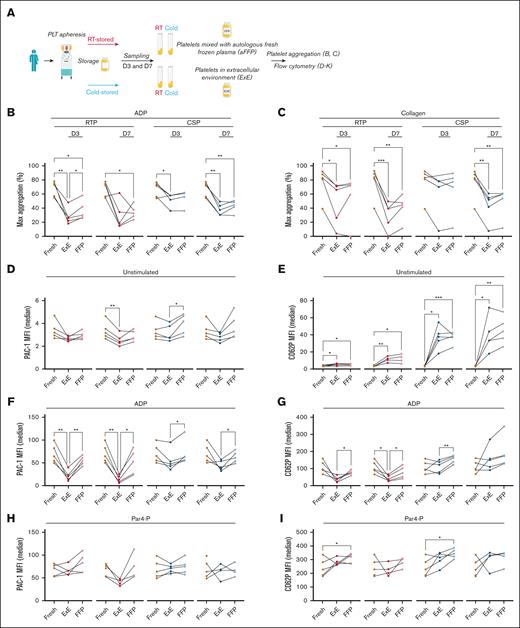

Human stored platelet function in different extracellular environments. Human platelets were collected by apheresis and stored as RTP and CSPs for 7 days. Testing was performed after 3 days and at the end of storage (7 days). (A) Outline of the sequence of study events. (B-C) Light transmission aggregometry data (shown as % of maximum aggregation) using either RTP (red dots) or CSP (blue dots) diluted either with FFP or using concomitant stored plasma (ExE). Platelets were stimulated with either 20μM ADP (B) or 5 μg/mL of collagen (C). (D-K) The same groups as outlined above were tested using flow cytometry for αIIbβ3 integrin activation by adding PAC1 antibody (D,F,H,J) or for α-degranulation by adding P-selectin antibody (E,G,I,K) (all data acquired as median MFI). Platelets were tested as baseline (D-E) (ie, no agonist) or after the addition of 20μM ADP (F-G), 1mM Par4-P (H-I), and 100 ng/mL of CVX (J-K). Graphs show individual data points (n = 4-5). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. Lines between dots have been added to identify individual data points between fresh and dilution with ExE and FFP and do not represent continuity or timeline. Statistical analysis with 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. D3, day 3; D7, day 7; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PLT, platelet.

Human stored platelet function in different extracellular environments. Human platelets were collected by apheresis and stored as RTP and CSPs for 7 days. Testing was performed after 3 days and at the end of storage (7 days). (A) Outline of the sequence of study events. (B-C) Light transmission aggregometry data (shown as % of maximum aggregation) using either RTP (red dots) or CSP (blue dots) diluted either with FFP or using concomitant stored plasma (ExE). Platelets were stimulated with either 20μM ADP (B) or 5 μg/mL of collagen (C). (D-K) The same groups as outlined above were tested using flow cytometry for αIIbβ3 integrin activation by adding PAC1 antibody (D,F,H,J) or for α-degranulation by adding P-selectin antibody (E,G,I,K) (all data acquired as median MFI). Platelets were tested as baseline (D-E) (ie, no agonist) or after the addition of 20μM ADP (F-G), 1mM Par4-P (H-I), and 100 ng/mL of CVX (J-K). Graphs show individual data points (n = 4-5). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. Lines between dots have been added to identify individual data points between fresh and dilution with ExE and FFP and do not represent continuity or timeline. Statistical analysis with 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. D3, day 3; D7, day 7; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PLT, platelet.

Flow cytometry

For pretransfusion testing, we sampled platelets fresh and after storage. Platelets were adjusted to a working concentration of 30 × 103/μL using exogenous concomitant storage plasma (ExE) or fresh frozen plasma (description in supplemental Methods). Platelet function was tested by flow cytometry (LSR II; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Platelets were identified by forward and side scatter plots and Leo.F2 positive events. The samples were stimulated with different agonists (0.5mM PAR-4 peptide [Par4-P], 100 ng/mL of convulxin (CVX), and 20μM ADP) and analyzed for mouse αIIbβ3 activation using Jon/A-PE antibody.

In vivo hemostasis assay

Platelet depletion was induced as described by our research group and others.28,29 In brief, we injected hIL-4Rα/GPIbα–Tg mice30 with an antibody against hIL4Rα and thereby rendered them thrombocytopenic (supplemental Methods). In this study, thrombocytopenic hIL-4Rα/GPIbα–Tg mice (called as hIL-4R mice for the rest of the manuscript) were used as the recipient mice for platelet transfusion and in vivo assessment of hemostasis. Platelets were isolated from wild-type (WT) whole blood and WT platelets were stored in the cold or at RT for 24 hours for transfusion. On the day of the experiment, the stored platelets were labeled in vitro before transfusion with a commercially available nonfunction-blocking antiplatelet antibody designed for in vivo intravital microscopy imaging (anti-GPIbβ–DyLight-488, Emfret Analytics) before transfusion. Hemostatic clot formation in response to penetrative laser injury to the cremaster arterioles was examined under intravital microscopy in thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice transfused with CSPs and RTPs as described.31,32 In brief, thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (100 and 10 mg/kg, respectively). A jugular catheter was established for transfusion and injections.

The cremaster arterioles (30-50 μm in diameter) were surgically exposed under a dissecting microscope and perfused with warm bicarbonate saline throughout the experiment. Blood flow through the cremaster arterioles was visualized under a fluorescent microscope’s 63× water-immersion objective lens equipped with a solid laser launch system (Zeiss Axio Examiner Z1; Zeiss Group, Jena, Germany). The mice were then transfused with 4 × 108 of Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescently labeled RTPs or CSPs suspended in a volume of 200 μL, followed by IV injection of Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated antimouse fibrin antibody (0.3 μg/g) via a jugular vein catheter. Thirty minutes after platelet transfusion, the arteriole vessel was exposed to a high-intensity laser pulse to puncture a hole of 7 to 12 μm in diameter through the wall. The penetrating injury to the vessel wall was confirmed by the extravasation of blood to the perivascular space and the immediate accumulation of platelet formation of fibrin at the site of vascular injury, which led to the cessation of bleeding. Hemostasis clot formation at the injury site was recorded in real time with a multichannel fluorescent intravital microscope, and multiple independent upstream vascular injuries were performed on the same mouse. Hemostatic response to injury was quantitated by the dynamics of platelet accumulation, and fibrin formation within the hemostatic clot at the site of injury was quantified by the change of fluorescence intensity using Slidebook 6.0 (3i, Denver, CO). The collaborating surgeon and data analyst were blinded to group allocations, and the primary laboratory performed the unblinding of the data, followed by graphing of the data.

Regulatory approvals

The Western institutional review board-Copernicus Group approved the study using blood from healthy humans. Written informed consent was obtained. We conducted the study following the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors had access to the reported data. All animal studies were approved by the Bloodworks Northwest Research Institute’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Our study examined male and female animals in approximately similar numbers, and similar findings are reported for both sexes.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation or standard error of the mean as indicated. For normally distributed data with homogenous variance, we used the unpaired or paired (as appropriate) 2-tailed t test (2 groups) or 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons (>2 groups). All platelet function analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9 (San Diego, CA), and the metabolome analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst.33 A P value of ≤ .05 was considered significant for platelet function tests. For the metabolomic analysis, an false discovery rate (FDR) with q < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In vitro function of stored human platelets in different extracellular environments

To explore the role of the extracellular milieu in platelet function, we obtained human apheresis platelets and processed and sampled them as outlined in Figure 1A and Study design and methods. The donor demographics are shown in supplemental Table 1. Storage generally decreased the aggregation response compared to fresh platelets, regardless of the dilution plasma type and time point (Figure 1B,C). Dilution with autologous fresh frozen plasma (FFP) only significantly improved aggregation in 3-day RTPs after stimulation with ADP (Figure 1B). Using flow cytometry as a more sensitive test to assess αIIbβ3 integrin activation and α-degranulation, we found that dilution in FFP alone increased integrin activation only in CSPs without addition of agonists (Figure 1D). Storage itself led to α-degranulation as previously described13 and more so in CSPs than in RTPs, but dilution with FFP alone did not affect α-degranulation significantly (Figure 1E). Similar to the aggregation studies, stimulation with ADP led to the most significant effect of dilution with FFP on integrin activation and α-degranulation in RTPs and CSPs (Figure 1F,G). In contrast, Par4-P only led to more α-degranulation in 3-day stored RTPs and CSPs, exceeding fresh α-degranulation levels, likely because of preexisting baseline preactivation induced by storage, followed by the strong Par4-P stimulus (Figure 1H,I). The clearest difference between RTPs and CSPs were found with CVX stimulation. Here, only significant improvements in integrin and α-degranulation were found in RTPs, but none was observed in CSPs (Figure 1J,K).

Pretransfusion and posttransfusion in vitro studies with murine platelets

Pretransfusion and posttransfusion function in recipient mice with normal platelet counts

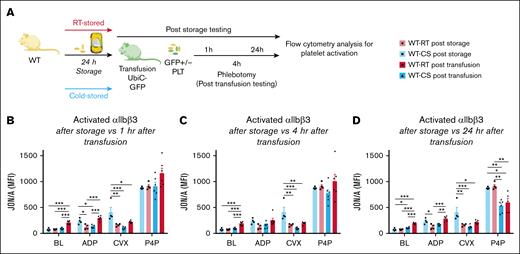

To test the ability of platelets to change function in vivo, we tested WT mouse RTPs and CSPs before and after transfusion in a platelet transfusion mouse model using mice ubiquitously expressing green fluorescent protein (UbiC-GFP mice) as recipients (Figure 2A). Before transfusion, CSP showed significantly increased αIIbβ3 integrin activation in response to ADP (Figure 2A,D).34 No significant difference was observed at baseline and after stimulation with Par4-P (Figure 2B-D). After transfusion, the response of RTPs and CSPs was reversed, with RTPs showing a significantly higher response to ADP (1 and 24 hours) than CSPs (Figure 2B,D). One hour after transfusion, RTPs also showed significantly more baseline activation (Figure 2B). In the following 24-hour time point, the significant difference at baseline and the improved response to ADP in RTPs over CSPs as well as the general trend for improved αIIbβ3 integrin function after stimulation with CVX and Par4-P persisted (Figure 2C-D). During all time points, the function of the endogenous platelets was significantly better than the function of the stored and transfused platelets (supplemental Figure 2).

Change of transfused platelet function in UbiC-GFP mice with normal platelet counts. Murine WT platelets were stored for 24 hours as CSPs or RTPs and tested at baseline (separate experiment) and after transfusion into UbiC-GFP mice (separate experiment) to allow for the identification of transfused and endogenous platelets. (A) Outline of experiments. (B) Platelet function after RTP (white bar with red outline, individual data points as black circles) or CSP (white bars with blue outline, individual data points as black squares) storage and 1 hour after RTP (solid red bars, individual data points as black circles) or CSP transfusion (solid blue bars, individual data points as black triangles). Same groups as in panel B but 4 hours (C) and 24 hours (D) after transfusion. Bar graphs show individual data points and indicate mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM, n = 4-6). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. Statistical analysis using 1-way ANOVA, with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons between groups. BL, baseline; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PLT, platelet.

Change of transfused platelet function in UbiC-GFP mice with normal platelet counts. Murine WT platelets were stored for 24 hours as CSPs or RTPs and tested at baseline (separate experiment) and after transfusion into UbiC-GFP mice (separate experiment) to allow for the identification of transfused and endogenous platelets. (A) Outline of experiments. (B) Platelet function after RTP (white bar with red outline, individual data points as black circles) or CSP (white bars with blue outline, individual data points as black squares) storage and 1 hour after RTP (solid red bars, individual data points as black circles) or CSP transfusion (solid blue bars, individual data points as black triangles). Same groups as in panel B but 4 hours (C) and 24 hours (D) after transfusion. Bar graphs show individual data points and indicate mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM, n = 4-6). ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. Statistical analysis using 1-way ANOVA, with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons between groups. BL, baseline; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PLT, platelet.

Pretransfusion and posttransfusion function in thrombocytopenic recipient mice

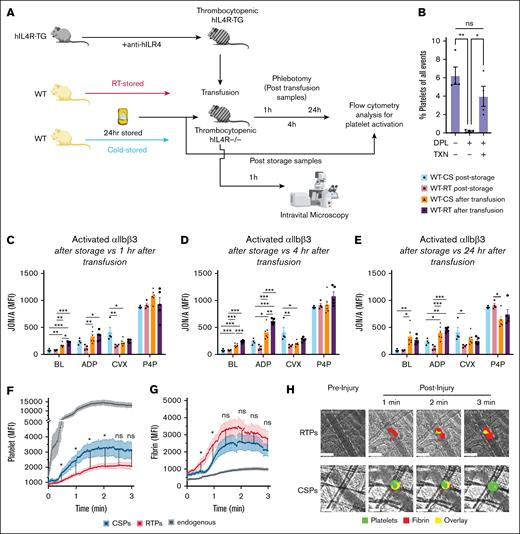

In the above tests, 2 competing platelet populations are in circulation and could affect each other’s function. To test whether the presence of an endogenous platelet population affects the in vivo change of function, we transfused stored murine WT RTPs and CSPs to thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice (Figure 3A). Because repeated retroorbital blood draws to measure platelet counts after retroorbital injection would have affected our ability to draw 1-, 4-, and 24-hour platelet function tests, we performed a separate experiment to show that the antibody administration results in profound thrombocytopenia and the following platelet transfusion lead to a significant platelet count increase. On average, 95% of all circulating platelets were transfused platelets, and ∼60% of the pretransfusion platelet count is reached with this approach (Figure 3B). The hIL4R depletion and adoptive transfer model allows for the transfusion of any mouse or human platelet that does not express the human interleukin-4 receptor α without affecting circulation times (as described in Study design and methods).28 We found a picture resembling that of stored platelet transfusion to mice with normal platelet counts. However, the posttransfusion function was only significantly different at baseline 1 and 4 hours after transfusion and after stimulation with ADP 4 hours after transfusion (Figure 3C,D), but not after 1 or 24 hours, hinting at a delayed and shorter-lasting effect of endogenous plasma on the transfused platelet population in thrombocytopenic recipients (Figure 3A,E). There was no significant difference between the contribution of CSPs vs RTPs to the circulating platelet population after transfusion, as shown by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 3).

Change of function in platelets transfused to thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice. Murine WT platelets were stored for 24 hours as CSPs or RTPs and tested at baseline (same data as in Figure 2) and after transfusion into hIL4R mice (separate experiment). (A) Outline of the experiment. (B) Efficiency of platelet depletion and platelet transfusion in hIL4-R-TG mice shown as % of circulating platelets of all circulating blood cells (n = 4). ∗P ≤ .05. Data shown as individual data points and mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. (C-E) Posttransfusion in vitro function (separate experiments from experiment shown in panel B. (C) Platelet function after RTP (white bar with red outline, individual data points as black circles) or CSP (white bars with blue outline, individual data points as black squares) storage and 1 hour after RTP (solid purple bars, individual data points as black circles) or CSP transfusion (solid orange bars, individual data points as black triangles). Same groups as in panel C but 4 hours (D) and 24 hours (E) after transfusion (n = 4-6). ∗P ≤ .05. Data shown as individual data points and mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis for panels C-E using 1-way ANOVA, with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons for between groups (prestorage vs poststorage). (F-H) Posttransfusion in vivo function. (F) Platelet and (G) fibrin accumulation at the injury site over 3 minutes. The red line with orange errors indicates the accumulation of RTP after injury, the blue line with light blue errors indicates the accumulation of CSP after injury, and the black line with light gray error bars indicates the accumulation of endogenous platelets in WT mice normal platelet counts. (H) Representative pictures of cremaster arterioles before (preinjury) and 1 to 3 minutes after (postinjury) injury. Anti–GP Ibβ-488 antibody as a platelet marker (green) for platelet accumulation, anti–fibrin-647 antibody as a fibrin marker (red) for fibrin formation, and overlay (yellow) within the hemostatic clot. The vessel is outlined by a dashed line, and the white scale bar indicates 50μM. Data are shown as mean + SEM, with n = 35 to 40 separate injuries per group obtained from 3 to 4 different mice per group. ∗∗P < .001; ∗P ≤ .05. Statistical analysis for panels F-G was conducted using unpaired Student t test with Holm-Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. BL, baseline; DPL, depleted; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant; TXN, transfused.

Change of function in platelets transfused to thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice. Murine WT platelets were stored for 24 hours as CSPs or RTPs and tested at baseline (same data as in Figure 2) and after transfusion into hIL4R mice (separate experiment). (A) Outline of the experiment. (B) Efficiency of platelet depletion and platelet transfusion in hIL4-R-TG mice shown as % of circulating platelets of all circulating blood cells (n = 4). ∗P ≤ .05. Data shown as individual data points and mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons. (C-E) Posttransfusion in vitro function (separate experiments from experiment shown in panel B. (C) Platelet function after RTP (white bar with red outline, individual data points as black circles) or CSP (white bars with blue outline, individual data points as black squares) storage and 1 hour after RTP (solid purple bars, individual data points as black circles) or CSP transfusion (solid orange bars, individual data points as black triangles). Same groups as in panel C but 4 hours (D) and 24 hours (E) after transfusion (n = 4-6). ∗P ≤ .05. Data shown as individual data points and mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis for panels C-E using 1-way ANOVA, with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons for between groups (prestorage vs poststorage). (F-H) Posttransfusion in vivo function. (F) Platelet and (G) fibrin accumulation at the injury site over 3 minutes. The red line with orange errors indicates the accumulation of RTP after injury, the blue line with light blue errors indicates the accumulation of CSP after injury, and the black line with light gray error bars indicates the accumulation of endogenous platelets in WT mice normal platelet counts. (H) Representative pictures of cremaster arterioles before (preinjury) and 1 to 3 minutes after (postinjury) injury. Anti–GP Ibβ-488 antibody as a platelet marker (green) for platelet accumulation, anti–fibrin-647 antibody as a fibrin marker (red) for fibrin formation, and overlay (yellow) within the hemostatic clot. The vessel is outlined by a dashed line, and the white scale bar indicates 50μM. Data are shown as mean + SEM, with n = 35 to 40 separate injuries per group obtained from 3 to 4 different mice per group. ∗∗P < .001; ∗P ≤ .05. Statistical analysis for panels F-G was conducted using unpaired Student t test with Holm-Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. BL, baseline; DPL, depleted; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant; TXN, transfused.

In vivo hemostasis challenge by cremaster arteriole injury

To compare our findings of posttransfusion in vitro function with those of posttransfusion in vivo function, we stored platelets as discussed above and transfused them to thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, CSPs led to significantly more platelet accumulation at the site of injury than RTPs from 30 seconds to 2 minutes but not thereafter (Figure 3F). In contrast, RTPs showed significantly more fibrin generation than CSPs between 30 and 60 seconds (Figure 3G). The receptor density for the major surface receptors was not significantly different between CSP and RTPs (supplemental Figure 4), with the exception of GPVI, which we have previously shown to be significantly lower in 100% plasma-stored CSPs.9 The platelet mean fluorescence intensity signal values obtained for depleted and transfused mice were markedly lower than those obtained for WT mice with normal platelet counts and normal platelet function (as depicted in the 2-part y-axis in Figure 3F). In contrast, fibrin generation was markedly lower in unaltered WT mice (Figure 3G). Representative images are shown in Figure 3H.

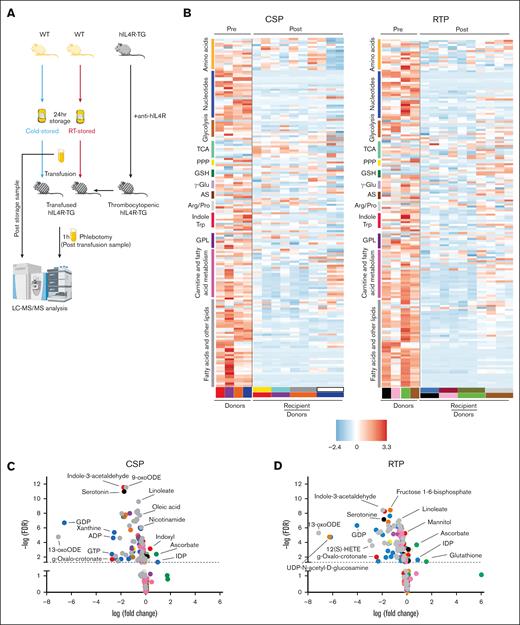

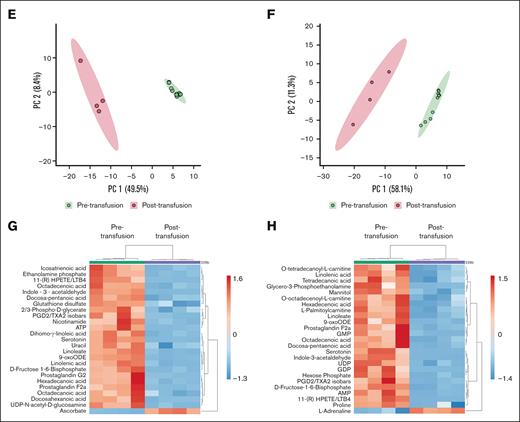

Pretransfusion and posttransfusion metabolomic changes of murine platelets

As described above, the adoptive transfer into an altered extracellular environment aids the recovery of the αIIbβ3 integrin activation, α-degranulation, and aggregation of stored platelets. To assess the metabolomic consequences of in vivo extracellular environment, we transfused stored platelet-rich plasma to thrombocytopenic hIL4R mice (as outlined above) and obtained platelets after transfusion for metabolomic analysis (supplemental Figure 5; Figure 4A). Mass spectrometry identified 172 biochemical compounds (supplemental Table 2; Figure 4B). In RTPs, 73% (125/172) of the metabolites changed significantly (q < 0.05) upon transfusion. In CSPs, 68% (117/172) of the metabolites changed significantly after transfusion (Figure 4C,D; as highlighted in supplemental Tables 3 and 4). In both groups, various metabolites decreased significantly, including nucleotides (eg, GDP, ADP, and GTP) and glycolysis metabolites. In addition, carnitine and fatty acid metabolites, as well as lipids, were significantly reduced in both groups. However, more carnitine and fatty acid metabolites were reduced in RTPs than in CSPs (Figure 4B-D; supplemental Table 5). Amino acids decreased in both groups, but more so in RTPs than in CSPs (Figure 4B-D; supplemental Table 5). The decrease in the number and specificity of glycerophospholipid metabolites was identical between CSPs and RTPs (supplemental Table 5). The polyamines spermidine and spermine decreased significantly in CSPs only. In RTPs, only 11, and in CSPs, 12 metabolites increased significantly upon transfusion (supplemental Table 6). Levels of d-ribose, glycolysis metabolites (d-glucose and 1-4-β-d-xylan), IDP, and inositol compounds increased significantly in both CSPs and RTPs (supplemental Table 6). Furthermore, ascorbate of the glutathione (GSH)-ascorbate cycle increased significantly at both storage temperatures, but GSH only in RTPs (Figure 4C,D; supplemental Table 6). The corresponding electron acceptors in the GSH-ascorbate cycle, the oxidized form of GSH (glutathione disulfide), and dehydroascorbate decreased significantly at both storage temperatures (supplemental Table 5). Interestingly, GSH in CSPs remained unchanged between storage and transfusion (P > .9) (supplemental Table 2). Because our analysis only includes the difference between the end of storage and after transfusion and to independently confirm the role of oxidative stress in stored platelets, we stored murine platelets and tested for total free thiols and reduced GSH at baseline and after storage in a separate set of experiments (supplemental Figure 6). We found that the percentage of both free thiols and reduced GSH decreased significantly over storage, highlighting the impact of oxidative stress on stored platelets compared to baseline (supplemental Figure 6). Indoxyl is part of both the indole and the tryptophan metabolism, and it increased significantly only in CSPs (Figure 4C). CSPs and RTPs showed increased N-acetylornithine levels compared to pretransfusion in arginine and proline metabolism, but creatinine increased significantly only in CSPs (supplemental Table 6). The dense granule component l-adrenaline increased only in RTPs after transfusion, but serotonin (also localized in dense granules) decreased significantly in both groups upon transfusion (Figure 4C,D; supplemental Table 5). In a principal component analysis, pretransfusion and posttransfusion samples clustered separately in both storage and transfusion groups (Figure 4E,F), hinting at significant changes upon transfusion regardless of storage temperature. To reduce variability between recipient samples, we averaged the posttransfusion samples of the recipients who received platelets from the same donor and performed a paired analysis (supplemental Figure 5). Approximately one-third of the top 25 significant clustered analytes were shared, whereas one-third was exclusively found in the RTPs vs CSPs (Figure 4G,H). CSPs and RTPs shared a surprising number of significantly downregulated metabolites, including the most abundant group, fatty acids and lipid components (CSPs, 14/25 [56%]; RTPs, 10/25 [40%]). Other examples were nucleotides and glycolysis metabolites. In contrast, carnitine metabolites were only significantly downregulated in the top 25 in the RTP group and the oxidative stress marker GSH in the CSP group.

Metabolism changes from pretransfuion to posttransfusion in murine platelets. (A) Visual outline of the study. (B) Heat maps of metabolites (mean-centered and divided by the standard deviation of each variable) of platelet-rich plasma (CSP, left panel; RTP, right panel) after storage (pretransfusion, left) and after transfusion into thrombocytopenic animals (posttransfusion, right). Metabolite groups are color-coded to correspond with volcano plots in (C-D). (C-D) Volcano plots of CSP (C) and RTP (D), with the colors of the dots corresponding to the metabolite groups in the heat maps. Dots above the dashed line are below the FDR significance cutoff of q = 0.05, following the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for P values derived from a 2-tailed, unpaired Student t test. Principal component analyses for CSPs (E) and RTPs (F). (G) Heat maps of the top 25 clustered metabolites in CSP with posttransfusion values averaged between recipients of the same donor. (H) Heat maps of the top 25 clustered metabolites in RTP with posttransfusion values averaged between recipients of the same donor. AS, amino sugars; FDR, false discovery rate; GPL, glycerophospholipid synthesis; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Metabolism changes from pretransfuion to posttransfusion in murine platelets. (A) Visual outline of the study. (B) Heat maps of metabolites (mean-centered and divided by the standard deviation of each variable) of platelet-rich plasma (CSP, left panel; RTP, right panel) after storage (pretransfusion, left) and after transfusion into thrombocytopenic animals (posttransfusion, right). Metabolite groups are color-coded to correspond with volcano plots in (C-D). (C-D) Volcano plots of CSP (C) and RTP (D), with the colors of the dots corresponding to the metabolite groups in the heat maps. Dots above the dashed line are below the FDR significance cutoff of q = 0.05, following the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for P values derived from a 2-tailed, unpaired Student t test. Principal component analyses for CSPs (E) and RTPs (F). (G) Heat maps of the top 25 clustered metabolites in CSP with posttransfusion values averaged between recipients of the same donor. (H) Heat maps of the top 25 clustered metabolites in RTP with posttransfusion values averaged between recipients of the same donor. AS, amino sugars; FDR, false discovery rate; GPL, glycerophospholipid synthesis; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Discussion

Our study presents a comprehensive functional and metabolomic analysis of stored platelets before and after altering the extracellular environment in vitro and in vivo. Our findings reveal a critical role of the extracellular environment for platelet function. Functionally, we provide data based on (1) in vitro change of function based on the addition of fresh plasma, followed by in vitro testing; (2) in vivo change of function, followed by in vitro testing; and, finally, (3) in vivo change of function, followed by in vivo testing. We found that RTPs changed their function more robustly upon transfusion in in vitro tests. This is possibly explained by the reversibility of changes after RT exposure compared to the relatively large temperature Δ between 37°C and 4°C, which could lead to more irreversible changes. Previous studies showed irreversible changes after extended (≥24 hours) cold storage.35-37 In the in vivo hemostasis mouse model, we found significantly more fibrin generation initially in RTPs even though CSPs led to more platelet accumulation, which was not predicted by posttransfusion in vitro tests. Enhanced pretransfusion baseline αIIbβ3 integrin activation has been described before by our research group and others.13,16,38 This activation may allow for a short-term “passive” platelet accumulation in vivo. Notably, the findings of our in vivo mouse model resemble those of a block-and-post flow chamber model and experiments using shear-induced aggregation with human platelets, in which CSPs outperformed RTPs in short-term adhesion and aggregation.9,39 Fibrin formation of both stored platelet groups exceeded fibrin formation by fresh, endogenous platelets. This finding suggests that this is a major way of stored and transfused platelets to support hemostasis, instead of platelet aggregation, which appeared to be inferior compared to the aggregation of endogenous, fresh platelets in normal numbers.

Our metabolomic analyses show that the transfusion of stored platelets induces significant changes in hundreds of metabolites, irrespective of the storage temperature, thereby altering numerous pathways. Despite well-documented metabolic differences between CSPs and RTPs, the striking similarity in pathway changes presents intriguing opportunities for further investigation. Fijnheer et al previously compared RTP function after storage before and after replacement with plasma. Similar to our findings, they found improved function after replacing stored extracellular supernatant plasma with fresh plasma.24 In accordance with their findings, we show that the effect of exogenous plasma is most pronounced with ADP as the agonist, likely because of P2Y12 desensitization during storage followed by resensitization after the addition of fresh plasma. We observed differences between CSPs and RTPs when we used the GPVI agonist CVX. Here, RTPs responded better, possibly due to the higher levels of GPVI expression in 100% plasma-stored platelets.9 A previous study on healthy humans investigated the effect of storage with subsequent transfusion on platelet quality, albeit with methodological limitations.40 In patients with thrombocytopenia, transfused platelet function improved significantly after 1 hour in circulation, as shown by flow cytometry responses to commonly used agonists.41 The P-selectin–positive platelet population quickly disappeared, likely due to accelerated clearance. Similarly, Miyaji et al showed universally improved platelet aggregation in patients with thrombocytopenia after transfusion vs pretransfusion-stored platelets.42 No difference was observed between stored, transfused platelets and endogenously produced platelets when platelet counts recovered to moderate levels in patients, highlighting the high potential of stored platelets to change their function. In contrast, we found that endogenous platelets were uniformly better than stored and transfused platelets throughout the experiment, regardless of storage temperature.

Our study aligns with these findings because it shows improved in vitro posttransfusion and in vivo posttransfusion function. Surprisingly, RTPs provided significantly more fibrin accumulation early at the injury site than CSPs, contradicting our previous findings in healthy humans, where CSPs generated more thrombin upon transfusion.15 Storage itself appears to prime platelets for fibrin generation considering that the fibrin generation with stored platelets far exceeded the fibrin generation in WT mice with normal platelet counts. A difference in storage time could explain this discrepancy. In the current murine study, both CSPs and RTPs were stored for the same period, whereas in the healthy human study, both were stored to the allowable Food and Drug Administration–licensed maximum (7 and 14 days, respectively).

In this study, we also carefully characterized the change of metabolites before and after transfusion. The oxylipin 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid [12(S)-HETE] is critically involved in platelet function after transfusion in mice29 and is associated with reduced platelet survival in humans.43 We found 12(S)-HETE severely downregulated after transfusion, among other oxylipins, including 13-oxooctadecadienoic acid (13-oxoODE) and 9-oxoODE. This highlights that the circulation time after these lipid mediators is probably shorter than our 1-hour testing time frame. The metabolic phenotypes of 5-day–stored RTPs were previously compared to those of up to 21-day–stored CSPs ex vivo.44 The authors found that cold storage led to decreased oxidative stress and delayed initiation of several pathways, including the pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis, and fatty acid metabolism in CSPs compared to that in RTPs.44 We found evidence for the role of transfusion in downregulating critical energy providing pathways in RTPs, more so than that in CSPs, including carnitines, as part of the fatty acid metabolism. This could explain why CSPs proved to be better at aggregating at the site of in vivo injury than RTPs, arguably a more energy-demanding process than the isolated functional in vitro assays.

Our study calls into question the general emphasis on the ex vivo testing of platelets to predict in vivo efficacy, especially after prolonged periods of ex vivo aging. To date, only a pH of <6.2 and the Kunicki morphology score have been identified as a strong predictor for poor platelet in vivo survival, but a pH of >6.2 does not indicate good survival.45,46 Other weaker metrics have been established, including platelet degranulation marker and adhesion receptor expressions such as P-selectin and GP Ibα, respectively.35,47 However, no single predictor of in vivo hemostatic function has been identified.

We found evidence for recovery from oxidative stress in both groups. In CSPs, the reduced forms of ascorbate and GSH increased significantly, and in RTPs, the oxidized form, glutathione disulfide and dehydroascorbate were significantly reduced. However, GSH did not increase in transfused CSPs, hinting possibly at incomplete recovery from oxidative stress after cold storage with subsequent transfusion.

Our study has limitations. Because we do not have prestorage (fresh) platelet-rich plasma data, downregulation was interpreted as a reversal of in vitro accumulation and an increase was interpreted as a reversal of a decrease after storage. Mouse platelets circulate for a markedly shorter time than human platelets (3-4 days compared to 7-10 days, respectively).48 Therefore, our 1-day storage time is akin to a 3- to 4-day storage time for human platelets, when most stored platelets are transfused clinically. Our data provide strong evidence for the critical role of transfused platelet change of function given the observed effect sizes for numerous identified changes in the platelet populations with transfusion. However, it is unclear what effect the clearance of the transfused platelets has on the analysis. Because the platelets and metabolites that are immediately cleared from circulation are no longer accessible for this analysis, we also do not know how the change in function is dependent on the recipient’s status, such as in trauma, sepsis, or surgery patients.

It is also important to note that our findings are only applicable when platelets are stored in 100% plasma. In some countries, most plasma is replaced with additive solutions.25 We currently do not know how additive solution affects the ability to change function upon transfusion.

We tested platelet-rich plasma instead of isolating a platelet pellet, and consequently, we detected plasma and platelet changes. Thus, we followed the clinical approach where platelets and concomitant plasma represent 1 transfused “unit,” whereas washed or volume-reduced platelets are rarely transfused. Moreover, at the site of injury in vivo, platelets and flowing plasma in the bloodstream act together to facilitate hemostasis. Nevertheless, a reductionist approach, where plasma and platelets are separated for testing, could be helpful in future studies. Further studies also need to address donor and recipient factors such as donor and recipient age, platelet circulatory age, and how they affect the platelet change of function potential.

In summary, our study allows us to approach storage conditions from a different angle compared to previous studies and address platelet transfusion quality.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the medical student Jeffrey Miles for his data acquisition and technical assistance in the manuscript. They also thank Anita Barberg, Halie Smith, and Tony White for their continuous administrative support.

M.S. received funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 1R01HL153072-01), and the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0441, EDMS 5570).

Authorship

Contribution: T.Ö. cowrote the first draft of the manuscript, designed and performed the experiments, and analyzed the data; S.L.B. designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data; A.C., D.A.B., H.J.J., J.D., M.R., and J.A.R. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; R.A., X.F., and A.D. designed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.S. designed the study, analyzed the data, provided funding, and cowrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors provided feedback on the final draft of the manuscript and had access to all data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S. reports research funding from Terumo BCT and Cerus Corp. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for T.Ö. is Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Correspondence: Moritz Stolla, Bloodworks Northwest Research Institute, 1551 Eastlake Ave E, Suite 100, Seattle, WA 98102; email: mstolla@bloodworksnw.org.

References

Author notes

All data from this article are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.