Key Points

Autocrine IL-2 is dispensable for the antileukemic activity of CD19-specific CAR T cells.

CRISPR-induced homology directed repair and prime editing can be combined for the vector-free generation of orthoIL-2–responsive CAR T cells.

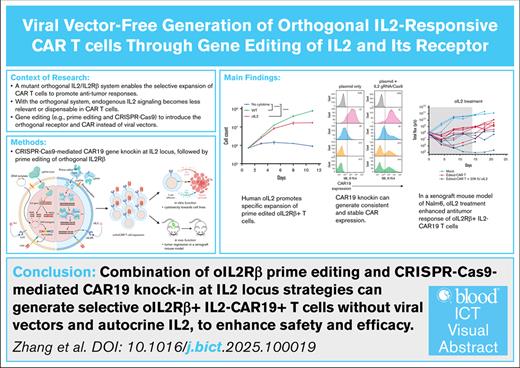

Visual Abstract

Building on the enhancing effects of the orthogonal interleukin-2 (oIL-2) system for T-cell immunotherapy, we explored a viral vector-free strategy for generating orthogonal chimeric antigen receptor (orthoCAR) T cells. We show that prime editing can generate orthogonal IL-2Rβ (oIL-2Rβ) mutations in T cells with an average efficiency of 72% (range, 54%-89%). The mutations are functional, enrich ex vivo when cultured with oIL-2 and enhance the engraftment, efficacy, and toxicity of CAR T cells in vivo comparable to orthoCAR T cells generated by cotransduction of the oIL-2Rβ and CAR. We further show that the insertion of a CD19-specific CAR with a chicken β-globin promoter into the IL-2 locus (IL-2–CAR19) can be achieved by a CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-triggered homology-directed repair with an average efficiency of 46% (range, 30%-65%) in primary T cells. IL-2–CAR19 T cells show a >3-log reduction in IL-2 production consistent with a >96% IL-2 gene disruption. Despite the loss of autocrine IL-2 secretion, IL-2–CAR19 T cells rapidly and potently kill NALM-6 leukemic cells in vitro and in vivo without the need for exogenous IL-2 support. Combining the prime editing of oIL-2Rβ with IL-2–CAR19 T cells yields orthoCAR T cells that exhibit in vitro and in vivo function comparable to lentivirally generated orthoCAR T cells. The prime editing of oIL-2Rβ expands the potential application of the orthogonal IL-2 system to existing T-cell therapies. Moreover, the robust functional activity of IL-2–CAR19 cells highlights the dispensable nature of the IL-2 gene in CAR T cells and its availability for the target insertion of genetic payloads.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is one of the most promising cancer immunotherapies, having shown significant efficacy in the treatment of hematologic malignancies of the B-cell lineage such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.1-8 Current CAR T-cell engineering methods primarily utilize viral vectors, especially retroviral and lentiviral vectors, to transfer genetic material into T cells to induce permanent CAR expression in T cells.9,10 Although viral vectors are powerful tools for gene delivery, the semirandom insertion of the vector into the genome leads to heterogeneous transgene expression likely related to the transgene promoter and its interaction with enhancer and silencer elements near the insertion site.11 Moreover, the random integration of the vector introduces a risk of insertional mutagenesis and dysregulated gene expression that can lead to oncogenesis, especially when these insertions occur in or near tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes.12,13 The targeted insertion of the CAR transgene into a single genomic site may not only reduce this oncogenic risk, but it also has the potential to improve the consistency of expression and the function of CAR T-cell therapies. Eliminating viral vectors from the process is also desirable because vector manufacturing adds complexity and cost to the production of commercial CAR T-cell therapies.14

In addition to improving CAR T-cell therapies through improved manufacturing approaches, combining T cells with other immunotherapeutic modalities will likely be needed to overcome the many barriers to effective cancer immunotherapy, especially in solid tumors. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is a key T-cell growth factor that has shown great potential in treating metastatic cancers.15-17 Despite its marked T-cell growth-promoting effects, its application in the clinic has remained limited due to significant toxicity that can be fatal.18 In an attempt to overcome the toxicity challenges associated with the clinical use of IL-2, the Garcia Laboratory developed a mutated version of IL-2 and the β-subunit of the IL-2 receptor to permit the targeted delivery of IL-2 signals specifically to engineered T cells, avoiding non–T-cell effects that may contribute to the observed toxicity.19 This mutated cytokine and cytokine receptor pair, which has been termed orthogonal IL-2 (oIL-2) and orthogonal IL-2Rβ (oIL-2Rβ), can specifically interact with each other but do not crossreact with their wild-type (WT) counterparts, transmit native IL-2 signals, and enable the selective expansion of the engineered CAR T cells expressing the oIL-2Rβ, with marked promotion of antitumor responses.20,21 This approach is currently in early phase clinical testing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT06544330 and NCT05665062).

In this study, we aimed to develop an orthogonal CAR (orthoCAR) T-cell therapy that can be generated without the need for viral vectors. Given that the orthogonal system should bypass the need for autocrine IL-2 secretion by T cells, we posited that the IL-2 gene could provide an ideal site for targeted CAR transgene insertion by homology-directed repair using CRISPR-based gene editing. Not only might the function of endogenous IL-2 be fully replaceable by the oIL-2 system, but the elimination of WT IL-2 secretion by CAR T cells might be helpful in limiting regulatory T (Treg) cells within the tumor microenvironment that are highly dependent upon this cytokine for survival. In our earlier work, we generated oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells by the codelivery of the entire oIL-2Rβ coding sequence with a CAR in a single lentiviral vector. Although this approach is effective, the >3-kb size of the entire transgene sequence challenges the cargo capacity of lentiviral vectors, which is also expected to increase the cost for vector manufacturing due to reduced titer. The limited number of mutations in oIL-2Rβ and their proximity suggested that prime editing, a more recently described gene editing approach that allows for site-specific sequence replacement, might be an effective method of generating oIL-2–responsive cells without the need for a viral vector. We show that combining prime editing and CRISPR knockin technologies is feasible to produce vector-free orthoCAR T cells with targeted CAR transgene insertion into the IL-2 locus and the concurrent disruption of the IL-2 gene. Moreover, our results reveal that the IL-2 gene is dispensable for CAR T-cell survival and function even without employing the oIL-2 system, supporting this locus as a potentially valuable genomic site for the genetic engineering of T cells.

Methods

Prime editing

The prime editing 3 (PE3) system was used for oIL-2Rβ editing. All prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) and nicking guide RNAs (ngRNAs) were designed using pegFinder (http://pegfinder.sidichenlab.org/) (supplemental Tables 1 and 2) based on oIL-2Rβ mutation sites.21 Prime editor mRNA was in vitro transcribed. A total of 2 × 106 TransAct-activated T cells in 20 μL of P3 buffer (Lonza Bioscience) were mixed with 4 μg of prime editor 2 (PE2) mRNA, 100 pmol of pegRNA, and 50 pmol of ngRNA and transferred to an electroporation strip (Lonza Bioscience), followed by electroporation using the 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza Bioscience) with code EO115.

CAR19 knockin at IL-2

A total of 5.8 μg of IL-2 guide RNA (gRNA) (supplemental Table 3) and 10 μg of Cas9 protein (Invitrogen) were incubated for 10 to 15 minutes at room temperature. A total of 2 × 106 activated T cells resuspended in P3 buffer at 20 μL were mixed with gRNA-Cas9 complex and 4 μg of CAR19 DNA template. This mixture was then transferred to the well of the nucleofector strip and electroporated using 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza Bioscience) with the pulse code EH115.

HDR donor template design and production

Donor templates were designed in SnapGene (GSL Biotech). To design CAR19 HDR templates, the Cas9 cut site at the IL-2 locus was identified within the vicinity of the desired knockin site. Subsequently, 0.65-kb nucleotides (nt) from 3 nt upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) were designated as left and right homology arms. The space between the homology arms contains the CBh promoter, the CAR19 gene, and a stop codon followed by a polyadenylation sequence.

In vivo xenograft studies

A total of 1 × 106 click green beetle/green fluorescent protein Nalm6 leukemic cells were injected into NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice on day 0 as previously described.22 The first bioluminescent imaging (BLI) measurement was conducted on day 4 to confirm tumor presence in mice followed by CAR T-cell infusion on day 5. On the same day, the mice then received human oIL-2 for 14 or 21 days. BLI was conducted twice per week to trace tumor growth and development in vivo. Peripheral blood was obtained every week for evidence of T-cell expansion. The quantification of serum cytokine concentrations was performed by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems).

Results

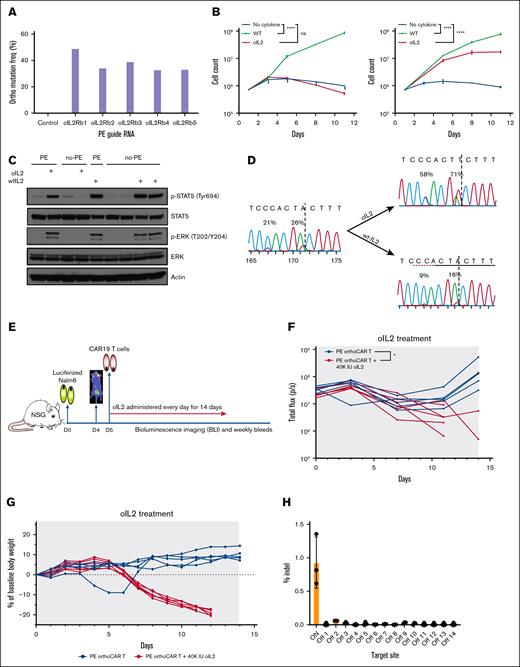

Prime editing of the endogenous IL-2Rβ locus is a feasible strategy for generating oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells

oIL-2 responsiveness depends upon the mutation of 2 adjacent amino acids [His133 → Asp (H133D) and Tyr134 → Phe (Y134F)] within IL-2Rβ in exon 6. This proximity suggested that prime editing could be effective in producing orthoCAR T cells. The efficiency of prime editing is influenced by several parameters within the pegRNA, including the lengths of the primer binding sequence (PBS) and reverse transcription (RT) template (RTT) as well as the position of RT initiation site.23,24 Therefore, we generated and screened 5 pegRNAs targeting exon 6 of IL-2Rβ in which the lengths of the PBS and RTT were varied (supplemental Table 1). The PE2 mRNA was used to improve the editing efficiency and decrease off-target effects,25 and the SeAx cell line, which is an IL-2–dependent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line, was used for screening for functional mutations.26 Although all pegRNAs screened were effective at generating the target orthogonal mutations, pegRNA01 containing the shortest 12-nt RTT and a 15-nt PBS yielded the highest efficiency, reaching ∼50% without oIL-2 selection (Figure 1A). The oIL-2Rβ mutations introduced into SeAx cells are also functional. oIL-2 was able to support prime-edited SeAx cell proliferation to similar levels of WT IL-2 (supplemental Figure 1). The prime editing efficiencies of oIL-2Rβ of >50% could also be achieved without selection with pegRNA01 in activated, primary human T cells (supplemental Figure 2), and robust expansion was observed with oIL-2 similar to WT IL-2 with the selection of the target mutations in the presence of oIL-2 (Figure 1B). As expected, prime-edited oIL-2Rβ cells exhibited phosphorylation of STAT5 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the presence of oIL-2 at levels comparable to WT IL-2 (Figure 1C). To determine whether oIL-2 selectively expands edited primary T cells capable of secreting their own IL-2, we generated T cells with a lower editing efficiency of ∼25%. After 7 days of oIL-2 culture, editing efficiency increased to slightly >50% compared with a reduction to less than half of the input mutation frequencies in WT IL-2 (Figure 1D). These data suggest that the oIL-2Rβ mutations may confer a selective disadvantage in the absence of the orthogonal ligand. To further confirm the functionality of the PE-generated oIL-2Rβ mutations, we performed prime editing after the transduction of primary human T cells with a CD19-specific CAR (PE–oIL-2Rβ–CAR-T cells). These cells showed similar in vitro effector function compared with nonedited CAR T cells (supplemental Figure 3). Using a well-established Nalm6 human xenograft model of acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a suboptimal dose of CAR T cells, oIL-2 treatment enhances the antileukemic activity of PE–oIL-2Rβ–CAR-T cells (Figure 1E-F). Importantly, PE–oIL-2Rβ–CAR-T cells also induce severe weight loss and mortality when treated with relatively high doses of oIL-2, similar to the toxicity observed with lentiviral-delivered oIL-2Rβ that we previously reported is associated with robust T-cell expansion at this oIL-2 dose. In aggregate, these data demonstrate the highly functional nature of the prime-edited IL-2Rβ gene that is comparable in function to lentiviral delivery of oIL-2Rβ (Figure 1G; supplemental Figure 4).

Prime editing of the endogenous IL-2Rβ locus is a feasible strategy for generating oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells. (A) Experimental validation of PE3-mediated functional oIL-2Rβ editing with the optimized pegRNA. To achieve ideal editing efficiency, we evaluated 5 pegRNAs with different lengths of RTT and PBS (supplemental Table 1) using SeAx, an IL-2–dependent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line. The impact of each pegRNA on editing efficiency was assayed using next generation sequencing (NGS). (B) Human oIL-2 promotes the specific expansion of the human primary T cells expressing the edited oIL-2Rβ. The nonedited and edited oIL-2Rβ human primary T cells were cultured in the media with 20nM of human WT IL-2 or oIL-2. To monitor cell expansion, cells were counted every other day over an 11-day period. Growth trends were visualized by comparing mock editing (left) and orthogonal editing (right) conditions, as shown in the corresponding growth curves. (C) Western blot analysis of human oIL-2–induced signal pathways through the edited oIL-2Rβ. The edited and nonedited T cells were stimulated with oIL-2 or WT IL-2 for 20 minutes followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. Actin served as the loading control. (D) Human oIL-2 selectively expands the T cells toward oIL-2Rβ+ cells. The activated human primary T cells were edited with a 25% oIL-2Rβ editing efficiency. After 7 days of culture, the editing efficiency increased to >50% in the presence of oIL-2 and halved in the presence of WT IL-2. (E) A diagram of the in vivo evaluation of prime-editing edited oIL-2Rβ+ CAR T cells (PE ortho/LV-CAR-T) antileukemic activity with human oIL-2 treatment. NSG mice were engrafted with 0.8 × 106 to 1 × 106 click green beetle (CBG)-labeled CD19+ Nalm6 leukemic cells on day 0 (Nalm6-LUC). A total of 1 × 106 PE orthoIL-2Rβ–CAR-T cells were injected on day 5 following BLI on day 4. phosphate-buffered saline or 40 000 IU of oIL-2 was administered via intraperitoneal route once a day for 14 days starting on day 5. Tumor burden was assessed via BLI twice per week, and CAR T-cell expansion was examined weekly. (F) Individual BLI intensity of Nalm6-LUC was determined for each mouse. Blue indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T; red indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T + 40 000 IU orthohIL-2. (G) Body weight of individual mice during the in vivo experiment from panel F. Mouse body weight was normalized to the body weight on day 0 for each mouse. Blue indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T; red indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T + 40 000 IU orthohIL-2. (H) Off-target evaluation for prime editing using NGS. Three-step polymerase chain reactions were performed with the genomic DNA from the 3 edited donors using the primers (supplemental Figure 5). Paired-end 2 × 250-bp reads were sequenced using MiSeq (Illumina) at 10.4pM along with 20.5% PhiX (University of Pennsylvania). The bar graph shows the indel percent of on- and off-target edits analyzed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). NSG, NOD scid gamma; orthohIL-2, orthogonal human interleukin-2; p-ERK, phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase; p-STAT5, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5.

Prime editing of the endogenous IL-2Rβ locus is a feasible strategy for generating oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells. (A) Experimental validation of PE3-mediated functional oIL-2Rβ editing with the optimized pegRNA. To achieve ideal editing efficiency, we evaluated 5 pegRNAs with different lengths of RTT and PBS (supplemental Table 1) using SeAx, an IL-2–dependent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line. The impact of each pegRNA on editing efficiency was assayed using next generation sequencing (NGS). (B) Human oIL-2 promotes the specific expansion of the human primary T cells expressing the edited oIL-2Rβ. The nonedited and edited oIL-2Rβ human primary T cells were cultured in the media with 20nM of human WT IL-2 or oIL-2. To monitor cell expansion, cells were counted every other day over an 11-day period. Growth trends were visualized by comparing mock editing (left) and orthogonal editing (right) conditions, as shown in the corresponding growth curves. (C) Western blot analysis of human oIL-2–induced signal pathways through the edited oIL-2Rβ. The edited and nonedited T cells were stimulated with oIL-2 or WT IL-2 for 20 minutes followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. Actin served as the loading control. (D) Human oIL-2 selectively expands the T cells toward oIL-2Rβ+ cells. The activated human primary T cells were edited with a 25% oIL-2Rβ editing efficiency. After 7 days of culture, the editing efficiency increased to >50% in the presence of oIL-2 and halved in the presence of WT IL-2. (E) A diagram of the in vivo evaluation of prime-editing edited oIL-2Rβ+ CAR T cells (PE ortho/LV-CAR-T) antileukemic activity with human oIL-2 treatment. NSG mice were engrafted with 0.8 × 106 to 1 × 106 click green beetle (CBG)-labeled CD19+ Nalm6 leukemic cells on day 0 (Nalm6-LUC). A total of 1 × 106 PE orthoIL-2Rβ–CAR-T cells were injected on day 5 following BLI on day 4. phosphate-buffered saline or 40 000 IU of oIL-2 was administered via intraperitoneal route once a day for 14 days starting on day 5. Tumor burden was assessed via BLI twice per week, and CAR T-cell expansion was examined weekly. (F) Individual BLI intensity of Nalm6-LUC was determined for each mouse. Blue indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T; red indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T + 40 000 IU orthohIL-2. (G) Body weight of individual mice during the in vivo experiment from panel F. Mouse body weight was normalized to the body weight on day 0 for each mouse. Blue indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T; red indicates PE ortho/LV-CAR-T + 40 000 IU orthohIL-2. (H) Off-target evaluation for prime editing using NGS. Three-step polymerase chain reactions were performed with the genomic DNA from the 3 edited donors using the primers (supplemental Figure 5). Paired-end 2 × 250-bp reads were sequenced using MiSeq (Illumina) at 10.4pM along with 20.5% PhiX (University of Pennsylvania). The bar graph shows the indel percent of on- and off-target edits analyzed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). NSG, NOD scid gamma; orthohIL-2, orthogonal human interleukin-2; p-ERK, phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase; p-STAT5, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5.

Genomic damage outside of the target site due to off-target editing is a major concern with gene editing approaches. PE has been reported to possess a low-level off-target activity due to the absence of double-strand breaks (DSBs) and the requirement for both a pegRNA and ngRNA.27,28 Fourteen potential, off-target sites for pegRNA01 and 4 sites for the ngRNA were identified by Cas-OFFinder29 (supplemental Table 4). Using a 3-step polymerase chain reaction approach (supplemental Figure 5; supplemental Table 5) followed by next generation sequencing, no mutations were detected at a sensitivity of ∼0.1% within a range of 250 base pair (bp) of any predicted off-target sites, demonstrating the high fidelity of the prime editing approach (supplemental Figure 6A). Prime editors relying upon the H840A Cas9 mutant has been shown to generate DSBs due to residual nickase activity in the histidine–asparagine–histidine (HNH) endonuclease domain. Evaluating insertion-deletion (indel) at the target site shows a low frequency of <1.5% at the target site with 10-fold lower frequency at off-target sites (Figure 1H; supplemental Figure 6B). All these data demonstrate that prime editing is an effective strategy for generating oIL-2Rβ–expressing T cells with minimal genotoxic effects on the T cells.

Targeted insertion of a CD19-specific CAR into the IL-2 gene-by-gene editing produces highly functional T cells in vitro and in vivo

Based upon the effectiveness of the oIL-2 system, which operates outside of the natural, autocrine IL-2 system to promote engineered T-cell expansion, we hypothesized that the endogenous IL-2 gene would not be required for orthoCAR T cells and further that it could be a viable site for targeted CAR insertion. To test the viability of this approach, we designed a strategy employing CRISPR/Cas9 to induce DSBs within the IL-2 gene followed by HDR to insert a CAR with the promoter transgene. We evaluated 2 adjacent single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) around the translation initiation site adenine-thymine-guanine (ATG) of the IL-2 gene (supplemental Figure 7). Both sgRNAs were highly efficient at disrupting the IL-2 gene. Sequencing confirmed high frequency of out-of-frame indels of 96% and 89% compared to a nonbinding sgRNA as expected with DSBs repaired by nonhomologous end joining (supplemental Figure 8). This high indel frequency observed with sgRNA1 correlated with the loss of IL-2 protein expression in the target cells, which was undetectable by western blotting or in the supernatant by ELISA in edited cells after T-cell activation (Figure 2A-B). After confirming the efficiency of gene targeting, we next tested the CRISPR/Cas9 editing in combination with an HDR template containing a novel hybrid form of the CBA promoter (CBh) that offers advantage over other promoters in terms of the CAR integration efficiency (supplemental Figure 9) and provides robust, long-term expression in all cells in combination with a second generation, CD19-specific CAR employing 4-1BB costimulation.30 The promoter-CAR transgene cassette was flanked 5′ and 3′ by 650 bp of sequence homologous to the sgRNA target site with the IL-2 gene (Figure 2C; supplemental Table 6). We chose a nanoplasmid, a nonviral plasmid vector for the template DNA, which can improve transfection efficiencies through its small backbone size (439 bp) and purposeful elimination of antibiotic selection systems and bacterial coding regions that induce innate immune responses through pathogen-associated molecular patterns or danger-associated molecular patterns.31 In the initial experiments evaluating a titration of the nanoplasmid template from 0 to 4 μg per million T cells, the highest CAR expression was observed in cells receiving 3 μg of nanoplasmids per million cells (supplemental Figure 10). Given that expression may derive from nonintegrated donor DNA, we also performed time course experiments with and without cotransfection of the sgRNA. CAR expression in the absence of sgRNA was significant in the first 2 to 3 days following transfection; however, this expression decreased to background levels by day 6 posttransfection compared with sustained expression in the presence of the sgRNA, confirming that sustained expression requires genomic integration (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 11). The expected insertion into the IL-2 locus was also confirmed by amplicon-based sequencing (supplemental Figure 12). The analysis of integrated CAR expression across multiple manufacturing runs and donors demonstrated an approximately eightfold lower CAR expression from the IL-2–inserted CAR compared to lentiviral vector–integrated CAR (Figure 2E upper panel). This difference is likely related to the different promoters used. Lentiviral integration also exhibited greater variability in expression across T cells within individual products based upon a higher percent coefficient of variation for the fluorescent intensity (Figure 2E lower panel). Considering that SpCas9 can tolerate mismatches between the sgRNA and genomic DNA leading to nuclease activity at sites with high sequence similarity, we evaluated the IL-2 sgRNA for off-target activity. We employed Cas-OFFinder, a bioinformatics prediction approach, to predict potential off-target sequences with up to 4 mismatches between the IL-2 sgRNA and the target sequence, with a bulge also permissible. A total of 13 putative off-target sites were identified and evaluated using amplicon-based sequencing (supplemental Figure 13A-B; supplemental Table 7). No indels or mutations were observed outside of the intended target sequence within IL-2, demonstrating the specificity of the gRNA/Cas9 RNP (supplemental Figure 13C-D).

Targeted insertion of a CD19-specific CAR into the IL-2 gene-by-gene editing produces highly functional T cells in vitro and in vivo. (A-B) IL-2–sgRNA:Cas9-mediated cleavage of the human interleukin-2 (hIL-2) protein. The edited and control T cells after 3-day electroporation were treated with protein kinase C activator TPA and calcium ionophore A23187 for 45 minutes to induce IL-2 production, followed by the overnight addition of brefeldin A or dimethyl sulfoxide (control) to block IL-2 secretion before collecting supernatant and lysing the cells. Intracellular and supernatant IL-2 protein levels were detected by western blot (A) and ELISA (B). LV-CAR and KI-CAR T cells represent transduced and edited CAR T cells, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3; a paired t test). (C) A diagram of CRISPR/Cas9-targeted CAR19 gene integration into the IL-2 locus. Upper portion: sgRNA-targeting sequence (green), PAM sequence (red), ATG (underline), and a vertical arrowhead for cleavage site. Middle portion: the genomic organization of the human IL-2 gene with exons represented by boxes and coding domains (cyan). Lower portion: donor DNA sequence containing an LHA (white), a promoter (gray), 19BBζ CAR coding sequence, polyA, and RHA (cyan) sequence (supplemental Table 6). (D) Representative flow cytometry showing the kinetics of nonintegrated and integrated CAR expression from nanoplasmid-encoded CAR transgene. TransAct-stimulated T cells were transfected with nanoplasmids with or without the sgRNA-Cas9 complex, followed by flow cytometry for checking CAR expressions at days 3, 6, 10, and 13 postelectroporation. Flow cytometry analysis showed that nonintegrated CAR expression was eliminated on day 6, whereas integrated CAR expression remained detectable on day 10 postelectroporation. (E) CAR MFI and CAR CV of CAR+ T cells (n = 12 independent experiments). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (Welch's 2 samples t test). (F) The killing potential of the IL-2–targeted CAR (KI-CAR) T cells vs transduced CAR T cells (LV-CAR T) was evaluated using xCELLigence RTCA eSight. Cytotoxicity against green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing Nalm6-CD19 target cells was evaluated at effector-to-target ratios (E:T) of 1:1 and 0.5:1 as depicted in the figure. Unedited T cells (mock) and target cells with or without 0.1% Triton X-100 (100% lysis control) were used as controls. The percentage of target cell death was quantified based on the confluency of GFP-labeled target cells followed by CAR T-cell addition. (G) The percentage of target cell death was quantified using the AUC of GFP-labeled target cells following CAR T-cell addition. E:T ratio = 1:1. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 Statistical significance was determined by repeated measures 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons (n = 3). (H) ELISA detection of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the cultured supernatants of CAR T cocultured with Nalm6-CD19 cells for 24 hours at an E:T ratio of 2:1. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent donors. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Repeated measures 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons) (n = 3). (I) The evaluation of the antitumor efficacy of KI-CAR19 T cells in vivo using a mouse model of leukemia (Nalm6). The individual BLI intensity of Nalm6-LUC was determined for each mouse of KI-CAR19 and transduced CAR19 (LV-CAR T) groups (n = 5 mice per group). (J) The quantification of the total human CD45+, CAR+ T-cell, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets in the mice of the transduced or edited groups were assayed on day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using paired t tests. (K) The quantification of TN (naïve), TCM (central memory), TEM (effector memory), and TEMRA (effector memory RA) cell subpopulations of the transduced or edited groups on day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. ATG, adenine-thymine-guanine; AUC, area under the curve; CV, coefficient of variance; hIL-2, human interleukin-2; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; KI-CAR T, knockin chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; LHA, left homology arm; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; RHA, right homology arm; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Targeted insertion of a CD19-specific CAR into the IL-2 gene-by-gene editing produces highly functional T cells in vitro and in vivo. (A-B) IL-2–sgRNA:Cas9-mediated cleavage of the human interleukin-2 (hIL-2) protein. The edited and control T cells after 3-day electroporation were treated with protein kinase C activator TPA and calcium ionophore A23187 for 45 minutes to induce IL-2 production, followed by the overnight addition of brefeldin A or dimethyl sulfoxide (control) to block IL-2 secretion before collecting supernatant and lysing the cells. Intracellular and supernatant IL-2 protein levels were detected by western blot (A) and ELISA (B). LV-CAR and KI-CAR T cells represent transduced and edited CAR T cells, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3; a paired t test). (C) A diagram of CRISPR/Cas9-targeted CAR19 gene integration into the IL-2 locus. Upper portion: sgRNA-targeting sequence (green), PAM sequence (red), ATG (underline), and a vertical arrowhead for cleavage site. Middle portion: the genomic organization of the human IL-2 gene with exons represented by boxes and coding domains (cyan). Lower portion: donor DNA sequence containing an LHA (white), a promoter (gray), 19BBζ CAR coding sequence, polyA, and RHA (cyan) sequence (supplemental Table 6). (D) Representative flow cytometry showing the kinetics of nonintegrated and integrated CAR expression from nanoplasmid-encoded CAR transgene. TransAct-stimulated T cells were transfected with nanoplasmids with or without the sgRNA-Cas9 complex, followed by flow cytometry for checking CAR expressions at days 3, 6, 10, and 13 postelectroporation. Flow cytometry analysis showed that nonintegrated CAR expression was eliminated on day 6, whereas integrated CAR expression remained detectable on day 10 postelectroporation. (E) CAR MFI and CAR CV of CAR+ T cells (n = 12 independent experiments). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (Welch's 2 samples t test). (F) The killing potential of the IL-2–targeted CAR (KI-CAR) T cells vs transduced CAR T cells (LV-CAR T) was evaluated using xCELLigence RTCA eSight. Cytotoxicity against green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing Nalm6-CD19 target cells was evaluated at effector-to-target ratios (E:T) of 1:1 and 0.5:1 as depicted in the figure. Unedited T cells (mock) and target cells with or without 0.1% Triton X-100 (100% lysis control) were used as controls. The percentage of target cell death was quantified based on the confluency of GFP-labeled target cells followed by CAR T-cell addition. (G) The percentage of target cell death was quantified using the AUC of GFP-labeled target cells following CAR T-cell addition. E:T ratio = 1:1. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 Statistical significance was determined by repeated measures 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons (n = 3). (H) ELISA detection of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the cultured supernatants of CAR T cocultured with Nalm6-CD19 cells for 24 hours at an E:T ratio of 2:1. Data represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent donors. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Repeated measures 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons) (n = 3). (I) The evaluation of the antitumor efficacy of KI-CAR19 T cells in vivo using a mouse model of leukemia (Nalm6). The individual BLI intensity of Nalm6-LUC was determined for each mouse of KI-CAR19 and transduced CAR19 (LV-CAR T) groups (n = 5 mice per group). (J) The quantification of the total human CD45+, CAR+ T-cell, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets in the mice of the transduced or edited groups were assayed on day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using paired t tests. (K) The quantification of TN (naïve), TCM (central memory), TEM (effector memory), and TEMRA (effector memory RA) cell subpopulations of the transduced or edited groups on day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. ATG, adenine-thymine-guanine; AUC, area under the curve; CV, coefficient of variance; hIL-2, human interleukin-2; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; KI-CAR T, knockin chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; LHA, left homology arm; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; RHA, right homology arm; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

To explore potential functional differences between IL-2–CAR19 T cells and conventionally transduced CD19-specific CAR T cells (LV-CAR19 T), we examined their cytolytic activity using the xCELLigence RTCA eSight platform and their antigen-induced cytokine production by ELISA. IL-2–CAR19 T cells were highly cytolytic, showing equivalent or better elimination of Nalm6 leukemic cells over time (Figure 2F-G) as well as greater interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor α secretion (Figure 2H). To determine whether the loss of autocrine IL-2 by CAR T cells affects their antitumor function in vivo, we evaluated IL-2–CAR19 T cells using the Nalm6 acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenograft model.32,33 IL-2–CART19 cells demonstrated durable control of Nalm6 leukemia comparable to LV-CAR19 T cells without additional in vivo cytokine support (Figure 2I; supplemental Figures 14 and 15) despite the reduced expansion observed ex vivo. IL-2–CAR19 T-cell -treated mice also demonstrated a significantly increased frequency of CD8+ T cells in mice receiving the IL-2–CAR19 T compared with mice receiving the LV-CAR19 (Figure 2J). A subset analysis showed that this increase spanned both naïve and memory CD8+ T-cell subsets (Figure 2K). In addition, the IL-2–CAR19 T cells can help prevent accelerated T-cell exhaustion compared to the LV-CAR19 (supplemental Figure 16). The sorting of CAR+ T cells from the spleen of IL-2–CAR19-T-cell -treated mice followed by amplicon-based sequencing demonstrated the expected HDR-mediated insertion of the CAR with the CBh promoter into the IL-2 site and a 99.5% indel frequency in nonintegrated loci, with an average of 1.92 CAR transgene copies per cell that was consistent with the biallelic knockin of most cells (supplemental Figure 17).

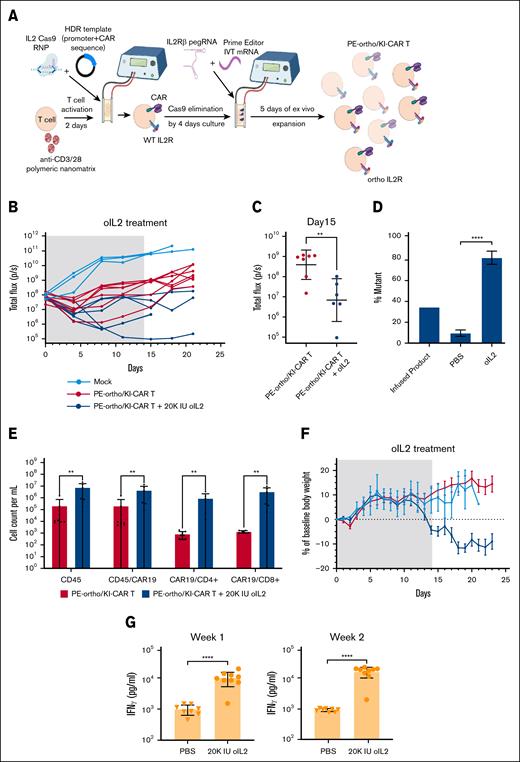

Prime editing of IL-2Rβ can be combined with IL-2 knockin for vector-free generation of oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells

Given the robust activity of the T cells with CAR inserted into the IL-2 gene by HDR, we posited that this approach could be combined with the prime editing of the IL-2Rβ gene to generate CAR T cells that can be driven by oIL-2 and manufactured without the use of a viral vector. The spCas9 used for CAR insertion by HDR uses the same PAM sequence as the PE2 prime editor. Therefore, we developed a sequential engineering approach in which orthogonal prime editing and CAR insertion by HDR were spaced temporally as shown in Figure 3A. This was based upon western blotting results that demonstrated a >98% reduction in spCas9 protein after 4 days following the first spCas9 RNP electroporation (supplemental Figure 18). To evaluate the functionality of dual-edited oIL-2Rβ+ IL-2–CAR+ T cells, we employed the same Nalm6 leukemic xenograft approach described in Figure 1E. A total of 1 × 106 oIL-2Rβ+ IL-2–CAR+ T cells with 57% CAR expression and an average IL-2Rβ orthogonal mutation frequency of 35% were injected IV into leukemia-bearing mice following 20 000 IU of mouse serum albumin–bound oIL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline. Nonedited, donor-matched T cells were used as a negative control. oIL-2Rβ+ IL-2–CAR T cells significantly delayed leukemia progression compared to nonedited T cells. The antileukemic activity of oIL-2–CAR T cells was significantly enhanced with oIL-2 support (Figure 3B-C; supplemental Figure 19). As expected, the frequency of IL-2Rβ orthogonal mutation increased with oIL-2 support (Figure 3D) as well as the overall concentration of CAR+ T cells in blood at 3 weeks following T-cell infusion (Figure 3E). Consistent with the enhanced CAR+ T-cell engraftment with oIL-2 treatment, there was also a reduction in body weight associated with an increase in serum interferon gamma (Figure 3F-G). This is similar to the toxicity observed in our earlier studies of the oIL-2 system using viral vector-based T-cell engineering.20 We also demonstrated that the edited orthoCAR T cells with optimal T-cell dose are able to control leukemia over several months at background levels of BLI that is comparable to orthoCAR T cells generated by lentiviral vector transduction (supplemental Figure 20). In addition, the CAR expression on T cells in vivo is stable compared to the expression observed in the edited CAR T-cell infusion product (supplemental Figure 21).

Prime editing of IL-2Rβ can be combined with IL-2 knockin for vector-free generation of oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells. (A) A schematic representation of PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 editing strategy. The first step is generating KI-CAR T cells. The IL-2–targeting sgRNA and Cas9 protein were incubated for 10 to 15 minutes at room temperature before adding donor template, followed by the addition of the TransAct-activated human primary T cells in P3 buffer. The mixture was transferred into the Lonza cuvettes and strip wells followed by electroporation using the pulse code EH115, resulting in the generation of KI-CAR T cells. After 3 to 4 days, PE2 mRNA, pegRNA, and ngRNA were cotransfected into KI-CAR T cells using the same 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza Bioscience) using the pulse code E0115, enabling the expression of oIL-2Rβ. (B) NSG mice were engrafted with 1 × 106 Nalm6 cells on day 0 and received 1 × 106 PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 T cells or nonedited cells (mock) as a control on day 5 following BLI on day 4. The mice with PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 T cells were divided into 2 groups: phosphate-buffered saline (red line) and oIL-2 (dark blue line). A total of 20 000 IU of oIL-2 was administered through intraperitoneal injection once a day for 21 days. Tumor burden was assessed by BLI twice per week (n = 5 mice per group). (C) The quantification of bioluminescence values of the phosphate-buffered saline-treated and oIL-2–treated groups. Comparison of BLI intensity between phosphate-buffered saline and oIL-2 treatment groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. (D) The total quantification of PE-mediated oIL-2Rβ mutation in the mice receiving oIL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline (n = 3) after PE-edited oIL-2–CAR T-cell infusion. ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (E) The total human CD45+, CAR+ T-cell, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets in the mice receiving oIL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline on day 14. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Red indicates the phosphate-buffered saline-treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group; blue indicates the oIL-2–treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group. (F) Mouse body weight of 3 different groups was normalized to the body weight on day 0 for each group over time until day 23. Light blue indicates the mock group; red indicates the phosphate-buffered saline-treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group; blue indicates the orthoIL-2–treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group. (G) The analysis of IFN-γ serum levels by ELISA in the phosphate-buffered saline-treated and oIL-2–treated mice on day 7 and 14 after T-cell infusion. The bars represent mean ± SD values with the range (n = 8). IFN-γ, interferon gamma; KI-CAR T, knockin chimeric antigen receptor T cell; ns, not significant; NSG, NOD scid gamma.

Prime editing of IL-2Rβ can be combined with IL-2 knockin for vector-free generation of oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells. (A) A schematic representation of PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 editing strategy. The first step is generating KI-CAR T cells. The IL-2–targeting sgRNA and Cas9 protein were incubated for 10 to 15 minutes at room temperature before adding donor template, followed by the addition of the TransAct-activated human primary T cells in P3 buffer. The mixture was transferred into the Lonza cuvettes and strip wells followed by electroporation using the pulse code EH115, resulting in the generation of KI-CAR T cells. After 3 to 4 days, PE2 mRNA, pegRNA, and ngRNA were cotransfected into KI-CAR T cells using the same 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza Bioscience) using the pulse code E0115, enabling the expression of oIL-2Rβ. (B) NSG mice were engrafted with 1 × 106 Nalm6 cells on day 0 and received 1 × 106 PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 T cells or nonedited cells (mock) as a control on day 5 following BLI on day 4. The mice with PE-ortho/KI-CAR19 T cells were divided into 2 groups: phosphate-buffered saline (red line) and oIL-2 (dark blue line). A total of 20 000 IU of oIL-2 was administered through intraperitoneal injection once a day for 21 days. Tumor burden was assessed by BLI twice per week (n = 5 mice per group). (C) The quantification of bioluminescence values of the phosphate-buffered saline-treated and oIL-2–treated groups. Comparison of BLI intensity between phosphate-buffered saline and oIL-2 treatment groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. (D) The total quantification of PE-mediated oIL-2Rβ mutation in the mice receiving oIL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline (n = 3) after PE-edited oIL-2–CAR T-cell infusion. ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (E) The total human CD45+, CAR+ T-cell, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subsets in the mice receiving oIL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline on day 14. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5 mice per group). Groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Red indicates the phosphate-buffered saline-treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group; blue indicates the oIL-2–treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group. (F) Mouse body weight of 3 different groups was normalized to the body weight on day 0 for each group over time until day 23. Light blue indicates the mock group; red indicates the phosphate-buffered saline-treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group; blue indicates the orthoIL-2–treated PE-ortho/KI-CAR group. (G) The analysis of IFN-γ serum levels by ELISA in the phosphate-buffered saline-treated and oIL-2–treated mice on day 7 and 14 after T-cell infusion. The bars represent mean ± SD values with the range (n = 8). IFN-γ, interferon gamma; KI-CAR T, knockin chimeric antigen receptor T cell; ns, not significant; NSG, NOD scid gamma.

Discussion

In this report, we show that oIL-2–responsive CAR T cells can be generated by combining 2 different gene editing technologies in a fully vector-free process. The specific gene editing tools employed to achieve genomic changes were selected for their well-established nature and wide use in the field. Vector-free manufacturing processes for the generation of CAR T cells may have several advantages over vector-based processes. These include eliminating vector production that can be complex and costly as well as potential safety concerns with randomly integrating viral vectors.34,35 Although the manufacturing process employed in our study is feasible, process improvement and especially simplification would significantly enhance clinical translation. Recent advances in combining gene editing technologies offer the potential to prevent translocations.36,37

The sequential electroporation used in our study was necessary due to the use of a common PAM sequence for the prime editing and CRISPR/Cas9-induced HDR. Cas9 proteins with alternative PAM sequence requirements exist.38 These could allow for multiplexing of the HDR and prime editing into a single step. Approaches to site-directed transgene insertion using a prime editor were also recently described that may have advantages over the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HDR approach used in our study. These include the twin prime editing and PASTE approaches.39,40 The former employs the prime editor to insert recombinase-specific sequences at the target site within the genome. These recombinase landing sites can then be used to mediate recombination without the DSBs required for HDR, thereby avoiding the potentially large chromosomal changes including large deletions, translocations, and entire chromosome loss that have been associated with these DSBs.41-46

Using the PE3 system, we do observe undesirable indels at the target site for our ngRNA with a frequency of ∼0.3% to 0.7% as well as indels at some predicted off-target sites (∼0.0%-0.02%). It is notable that our observed on- and off-target frequency is substantially lower than some published data for prime editing.28 This may be related to the more transient expression of PE2 achieved with the transfection of mRNA, which has been shown to reduce off-target prime editing.47 Although low frequency and none of the off-target genes with indels in our study are recognized tumor suppressor genes, these off-target edits are still undesirable. The proximity of the ngRNA target sequence to the prime editing site is an important factor affecting indel frequency. ngRNA target sequence that overlaps the prime editing site appears to show the lowest indel rates with prime editing. Unfortunately, there is no candidate sequence for an ngRNA sufficiently close to the target site of oIL-2Rβ. Lee et al recently demonstrated that the H840A HNH domain mutant of Cas9 used in PE3 to create a single-strand break on the PAM-containing DNA strand still induces DSBs, which may explain the occurrence of indels with prime editing.48 Additional mutation at N863A eliminates the residual HNH nuclease activity and reduces indels when incorporated in PE3, suggesting that this is one strategy that could be employed to help reduce unwanted indels.

From a more fundamental immunology perspective, our results also reveal that IL-2, a cytokine that is well-known for its T-cell growth-promoting effects, is not essential for functional CAR T cells. IL-2 has long been recognized to play important regulatory roles for T cells. It sensitizes conventional T cells to apoptotic cell death after antigen receptor engagement, which may contribute to the natural contraction of T cells after infection.49,50 Continuous exposure to IL-2 can also contribute to an exhaustion phenotype in CD8+ T cells through STAT5-driven expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor.51 Beyond conventional effector T cells, IL-2 is also critical to the survival and proliferation of Treg cells, which limit effector T cell responses and accumulate within many tumors contributing to immunotherapy resistance.52 These regulatory functions of IL-2 may be dominant over its proproliferative effects, explaining the inflammatory rather than immunodeficient phenotype of IL-2–deficient mice.53-55 Our ability to explore some of these regulatory effects with IL-2–CAR T cells, especially Treg effects, in the preclinical setting is greatly limited using human tumor xenograft models due to the lack of a functional immune system. The enhanced effector function of IL-2–CAR T cells observed in vitro compared with LV-CAR T cells might be due to the loss of these IL-2–mediated regulatory mechanisms; however, there are other important differences between IL-2–CAR T cells and LV-CAR T cells including the observed lower and less variable CAR expression, which has been shown to influence CAR function.56,57

The dispensable nature of autocrine IL-2 for CAR T cells also highlights the potential for exploiting this gene for genetically engineering T cells.58 Several other genomic sites have been described for targeted CAR transgene insertion, including AAVS1,56 TRAC,59,60 CCR5,61 PDCD,59 eGSH6,62 and CD3z.63 Compared to these other sites, the IL-2 gene has a natural promoter with high variable expression that relates to the state of T-cell activation. Although this was undesirable for CAR expression in our study, it was easily addressed with the use of a constitutive promoter coinserted with the CAR. There are transgenes where activation-induced expression could be desirable such as proinflammatory molecules such as IL-12 or IL-18 that are added to CAR T cells to enhance their function. Several groups have engineered T cells expressing these cytokines using artificial nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT)-driven promoters to avoid potential toxicity of constitutive expression.64-67 Given that the optimal IL-2 gRNA targets are within the translation initiation site of the gene, targeted insertion in frame with this start codon could theoretically accomplish the same objective with more tightly regulated expression by the natural IL-2 promoter that these artificial promoters attempt to replicate.

Finally, the efficiency of prime editing of the IL-2Rβ gene to generate oIL-2 responsiveness could vastly expand the applications of the oIL-2 system. Rather than reengineering a vector to include the entire IL-2Rβ gene, which would increase costs and perhaps reduce vector transduction efficiency due to the size of the transgene, prime editing only requires the addition of a physical transfection step such as electroporation or lipid nanoparticle to introduce the pegRNA and PE2 mRNA.68,69 This could greatly facilitate the incorporation of the oIL-2 system into existing T-cell therapies including CAR T cells, T-cell receptor T cells, or even tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of following facilities at the University of Pennsylvania: The Flow Cytometry Core for cell sorting, the Human Immunology Core for providing T cells from normal donors, the Translational and Correlative Studies Laboratory for providing T cells from normal donors, the Translational and Correlative Studies Laboratory for performing Luminex assays, and the Laboratory Animal Resources and the Stem Cell and Xenograft Core for the tumor and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell injections and drawing blood from mice.

This work was supported by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy grant (PICI), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant RO1AI51321 (K.C.G.); the Swiss National Science Foundation grant PP00P3-128421; the National Cancer Institute, NIH grant U54CA244711; and the Agilent Thought Leader Award.

Authorship

Contribution: Q.Z. contributed to the overall design of the study and experiments, supervised and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; Y.W., J.Y., and K.Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; E.N.E.A.M., T.W., A.Y., N.G., Y.Z., and M.E.H. performed the experiments; H.-Y.W. and I.S. analyzed the data; L.B., D.E.R., N.W.E., E.Z.S., S.N.-C., C.H.J., L.S., and K.C.G provided useful advice and reagents; C.H.J. and K.C.G also provided funding for parts of the research; M.C.M. conceived of and designed the study, provided funding, supervised project execution, and contributed to the data analysis and writing of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.C.M. is an inventor of the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell technology used in these studies (Methods for treatment of cancer, US patent no.: 8 906 682). This technology is owned by the University of Pennsylvania and licensed to Novartis AG. K.C.G. is the founder of Synthekine Therapeutics, which has licensed the orthogonal interleukin-2 (oIL-2) technology. K.C.G. and L.S. are inventors on a patent application describing the oIL-2 system (biologically relevant orthogonal cytokine/receptor pairs, United States Patent and Trademark Office patent no. 10869887B2). K.C.G. and L.S. are shareholders of Synthekine, a biotechnology company that has licensed the oIL-2 technology. M.C.M., Q.Z., and K.C.G. also have a pending patent application related to the work described (United States Patent and Trademark Office no. 18/316670). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael C. Milone, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 7.103 Founders Pavilion, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104; email: milone@pennmedicine.upenn.edu; and Qian Zhang, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 3400 Civic Center Blvd, Building 421, SPE 8-105, Philadelphia, PA 19104; email: qian2@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

References

Author notes

All sequence data (eg, primers and chimeric antigen receptor constructs) are provided in the supplemental Materials. For access to other original data, please contact the corresponding authors, Michael C. Milone (milone@pennmedicine.upenn.edu) and Qian Zhang (qian2@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.