Key Points

In grade 1 ICANS, positive findings were infrequent (3% of grade 1), with relevant findings only observed on MRI.

Our findings suggest brain MRI is useful for low-grade ICANS evaluation, but CSF analysis and EEG have low diagnostic yields.

Visual Abstract

Immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) is a potentially life-threatening toxicity of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CART) therapy, graded according to American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus guidelines. Patients with suspected ICANS are evaluated with neurodiagnostic testing, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and electroencephalogram (EEG) to establish ICANS grade and to evaluate alternate causes of symptoms. The study aims to determine the diagnostic yield of this testing for identifying alternative causes of altered mental status or in grading ICANS. This study is a retrospective review of 347 adult patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma who received commercial or investigational CART-targeting CD19 or B-cell maturation antigen at the University of Kansas Medical Center from December 2017 through November 2023. Of the 347 patients who received CART, 142 (41%) developed ICANS of any grade. Brain MRI identified alternative causes of neurologic symptoms in 13 (11%) patients. CSF analysis changed diagnosis in only 1 patient (1%) and no seizures were detected by EEG. These results suggest that brain MRI may assist with evaluation of ICANS, whereas EEG and CSF sampling rarely change diagnosis or alter clinical management.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CART) therapy is a promising option for patients with refractory/relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and multiple myeloma (MM).1-3 Immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) is a potentially life-threatening toxicity of CART, graded according to American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) guidelines.4 Patients with suspected ICANS are evaluated with neurodiagnostic testing, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and electroencephalogram (EEG) to establish ICANS grade and to evaluate alternate causes of symptoms.

ASTCT guidelines recommend initiating central nervous system (CNS) imaging, EEG, and lumbar puncture (LP) beginning at grade 1 or 2 ICANS; however, there is a paucity of data on the yield of these investigations in low grade ICANS.5 The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplant (EBMT) guidelines state “brain MRI and CSF evaluation are rarely helpful but can be used to rule out alternative diagnoses.”6(p141) The single reference to EEG utility is a recording “can be normal but can also demonstrate a pattern of variable abnormalities, including nonconvulsive status epilepticus.”6(p142) Due to lack of evidence for current recommendations, most investigations are initiated based on clinician preference, which may result in unnecessary procedures associated with increased risk, cost, and delay in management.

This descriptive study aimed to determine the diagnostic yield of CSF analysis, brain MRI, and EEG to identify alternative causes of altered mental status or in grading ICANS in CD19 and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CART recipients.

Study design

This study is a retrospective review of 347 adult patients with B-ALL, NHL, and MM who received CART-targeting CD19 or BCMA at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) from December 2017 through November 2023. Patients were included if they received investigational (n = 62) or commercial (n = 285) CART products targeting CD19 or BCMA.

KUMC’s institutional protocol for immune effector cell therapy management is adapted from the ASTCT guidelines.4 Management includes brain MRI, LP, and EEG obtained at the onset of grade 1 ICANS or based on physician discretion. Per institutional standards, all patients were admitted to the hospital for at least 7 days and evaluated for baseline neurocognitive status through neurology consultation. Intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring is required for patients with ICANS grade ≥2. All patients received equal doses of levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis from day 0 to 30, regardless of ICANS status. Treatment with steroids and other agents is initiated based on ASTCT guidelines.4

This study received institutional review board approval from KUMC and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Brain MRI “relevant findings” were defined as acute cerebral changes from baseline, including edema, hemorrhage, ischemic infarction, contrast-enhancing lesion(s), and T2/fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities.

Relevant findings from CSF analysis included CNS infections and newly identified CNS disease involvement that developed after CART infusion. CSF sampling includes white blood cell count, red blood cell count, neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, pathology interpretation, glucose, xanthochromia, and total protein.

Subclinical and clinical seizure activities were included as relevant findings from EEG. EEGs were 60 minutes and read by epilepsy specialists after using advanced software detection programs.

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to assess the frequencies and median counts of CSF samples, MRI scans, and EEGs following CART therapy. Additionally, the incidence of relevant findings from each modality was evaluated. Data analysis was performed using JMP Pro 17 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results and discussion

There were 347 CART recipients included in this study. Baseline demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic . | All patients (N = 347) . |

|---|---|

| Age at infusion, y | |

| Median | 64.2 |

| Mean | 61.99 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 289 (83.3) |

| Black | 26 (7.5) |

| Other | 32 (9.2) |

| Disease type, n (%) | |

| NHL | 250 (72.0) |

| MM | 80 (23.1) |

| ALL | 17 (4.9) |

| CART products, n (%) | |

| Axi-cel | 133 (46.7) |

| Ide-cel | 42 (14.7) |

| Tisa-cel | 39 (13.7) |

| Cilta-cel | 27 (9.5) |

| Brexu-cel | 26 (9.1) |

| Liso-cel | 18 (6.3) |

| CNS disease at infusion, n (%) | |

| Parenchymal | 14 (4.0) |

| Leptomeningeal | 3 (0.9) |

| CRS | |

| Incidence, all grade, n (%) | 254 (73.2) |

| Grade ≥3, incidence, n (%) | 10 (2.9) |

| ICANS | |

| Incidence, all grade, n (%) | 142 (40.9) |

| Grade ≥3, incidence, n (%) | 61 (27.6) |

| Grade 5, incidence, n (%) | 6 (1.7) |

| Steroid use | |

| Used at least 1 dose, n (%) | 156 (45.0) |

| Hospital admission | |

| >7 d, n (%) | 208 (59.9) |

| ICU transfer, n (%) | 81 (23.3) |

| Characteristic . | All patients (N = 347) . |

|---|---|

| Age at infusion, y | |

| Median | 64.2 |

| Mean | 61.99 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 289 (83.3) |

| Black | 26 (7.5) |

| Other | 32 (9.2) |

| Disease type, n (%) | |

| NHL | 250 (72.0) |

| MM | 80 (23.1) |

| ALL | 17 (4.9) |

| CART products, n (%) | |

| Axi-cel | 133 (46.7) |

| Ide-cel | 42 (14.7) |

| Tisa-cel | 39 (13.7) |

| Cilta-cel | 27 (9.5) |

| Brexu-cel | 26 (9.1) |

| Liso-cel | 18 (6.3) |

| CNS disease at infusion, n (%) | |

| Parenchymal | 14 (4.0) |

| Leptomeningeal | 3 (0.9) |

| CRS | |

| Incidence, all grade, n (%) | 254 (73.2) |

| Grade ≥3, incidence, n (%) | 10 (2.9) |

| ICANS | |

| Incidence, all grade, n (%) | 142 (40.9) |

| Grade ≥3, incidence, n (%) | 61 (27.6) |

| Grade 5, incidence, n (%) | 6 (1.7) |

| Steroid use | |

| Used at least 1 dose, n (%) | 156 (45.0) |

| Hospital admission | |

| >7 d, n (%) | 208 (59.9) |

| ICU transfer, n (%) | 81 (23.3) |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; Brexu-cel, brexucabtagene; Cilta-cel, ciltacabtagene autoleucel; CNS, central nervous system; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; Ide-cel, idecabtagene vicleucel; Liso-cel, lisocabtagene maraleucel; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; Tisa-cel: tisagenlecleucel.

Patients with NHL comprised 72% of the study population and had a median age of 64.3 years (range, 24.7-86.0). Patients with MM comprised 23% of the study population and had a median age of 66.6 years (range, 42.3-80.8). Patients with B-ALL comprised 4.89% of the study population and had a median age of 33.1 years (range, 19.9-68.3).

Incidence and patterns of ICANS

The incidence of ICANS was 41%. Among those with ICANS, 42% had grade 1 ICANS, whereas grade 2 was 15%, and grade ≥3 was 44%.

Brain MRI

Among those with any grade ICANS, 92% underwent brain MRI, and 11% had relevant findings. Findings included cerebral edema, new contrast-enhancing lesions, new ischemic stroke, new hygromas, FLAIR hyperintensities, and acute hemorrhages. The median number of MRIs performed per patient was 1 (range, 1-5). Of patients with ICANS who had an MRI, 15% (n = 2) had relevant findings from an MRI initiated at grade 0, 39% (n = 5) at grade 1, 23% (n = 3) at grade 2, 15% (n = 2) at grade 3%, and 4% (n = 1) at grade 4. In this population, there were 2 patients with relevant findings on MRI who, at the time of imaging, had not yet developed ICANS. One patient had an MRI due to persistent headache and was found to have cytotoxic edema within the splenium of the corpus callosum which was clinically attributed to ICANS as determined by the consulted neurologist. The other patient had an MRI to evaluate facial pain, and based on the findings, had no ICANS findings or alternate diagnosis.

CSF sampling

Among patients with ICANS, 72% underwent CSF sampling. A relevant finding was only identified in 1 patient with ICANS—a bacterial infection of the CSF. The median number of CSF analyses performed was 1 (range, 1-4). The examination with relevant CSF analysis findings was initiated at grade 3 ICANS.

EEG

Among patients with ICANS, 76% of patients underwent an EEG. Although 83% receiving an EEG had cerebral dysfunction or generalized slowing, no patients demonstrated seizure activity. The median number of EEGs performed was 1 (range, 1-8).

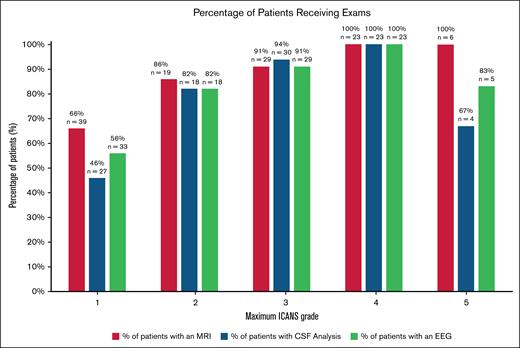

Incidence of patients receiving brain MRI, CSF analysis, and EEG per maximum ICANS grade. CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; EEG, electroencephalogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Incidence of patients receiving brain MRI, CSF analysis, and EEG per maximum ICANS grade. CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; EEG, electroencephalogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

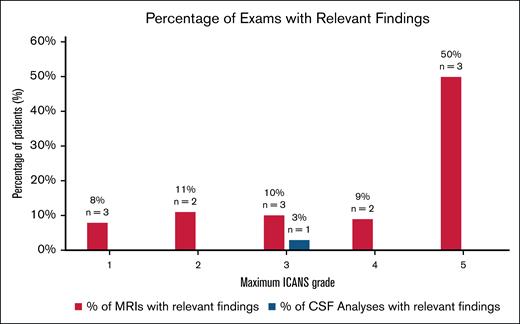

Incidence of relevant findings from brain MRI and CSF analysis per maximum ICANS grade. CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Incidence of relevant findings from brain MRI and CSF analysis per maximum ICANS grade. CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Grade of ICANS and yield of investigations

Among grade 1 patients, the number of patients whose ICANS grade changed based on investigations was 0%, whereas 3% (n = 3) had alternate diagnosis, all based on MRI findings. One patient had subdural hematomas, and the other had new acute infarcts. The third patient with persistent grade 1 ICANS had an MRI which identified a stroke. Similarly, for grade 2, only 4% (n = 2) had alternate diagnosis, whereas none had a change in grade based on investigations.

Among high grade ICANS, the number of patients whose ICANS grade changed based on investigations was 0.6% (n = 1) and 1% (n = 2) had alternate diagnoses. The one upgraded ICANS score was from an EEG finding, which upgraded the patient from grade 3 to 4.

This is the largest study to date on the utilization and yield of CSF analysis, MRI, and EEG during ICANS.7 The incidence of relevant MRI findings (11%) was consistent across ICANS grade 1 to 4, highlighting the utility of MRI even for grade 1. Our MRI findings for grade 1 ICANS are consistent with previous studies. In the literature, the largest study evaluating neurodiagnostic investigations in ICANS was a report on 190 CART patients, by Mauget et al.7 Their study found 9% of patients with grade 1 ICANS had abnormal brain MRI findings, supporting our conclusion that brain MRI should be initiated at grade 1 ICANS.

We report CSF analysis testing in most patients with ICANS (72%), but the yield was low. One patient with grade 3 ICANS had a relevant finding—a gram-positive bacterial infection later identified as Rhodococcus spp. This was the only patient whose clinical management of ICANS changed based on findings from CSF analysis. This is consistent with Mauget et al7 who reported 43 LPs performed during ICANS management with zero confirmed infections.

Our findings are important because of the potential risks of LP, especially in CART recipients with cytopenias. Although the rate of adverse events, such as spinal hemorrhage or iatrogenic infection, due to LP is low, a reported 10% to 40% of patients who undergo LP experience headaches or back pain.8 There may be concern for an increased risk of traumatic bleeding from an LP in thrombocytopenic CART patients.9

A wide range of seizure and subclinical seizure occurrences in CART recipients with neurotoxicity has been reported (1%-30%); however, not all electrographic findings are meaningful in ICANS management.10 Although 83% of patients who received an EEG had cerebral dysfunction, these findings were not specific and did not result in management changes. In our study, no EEGs showed seizure activity; however, EEG findings did rule out seizures in patients with suspected seizure activity. This is congruent with a study recommending initiating EEG at grade 2 ICANS due to a reported 12% (n = 6) of EEGs across all grades of ICANS showing seizures or status epilepticus in patients with ICANS.7 It is unknown what effect prophylactic antiseizure medication has on dampening clinically useful EEG findings in ICANS.

The major limitation of this study was that the data were retrospectively extracted from a single institution, which does not allow the comparison of patterns nationally. Additional limitations include disease heterogeneity and potentially differing toxicity levels for specific CART products.11

In conclusion, brain MRI identified the highest yield of abnormal findings, including alternate diagnoses, even in grade 1 ICANS. These results demonstrate a low utility of CSF analysis and EEGs to detect alternate diagnoses or to change the ICANS grading, which supports changing practice to reserve these examinations for patients with persistent grade 1 or higher grades of ICANS.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the patients who received CART and their families who received treatment at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Authorship

Contribution: N.A. designed the research; L.N.S. and B.H. wrote the manuscript; L.N.S., B.H., R.R., W.W., and P.T. collected data; P.T., M.H., F.L., Z.M., S.A., M.U.M., J.M., A.O.A., and M.M.N. reviewed the manuscript; and D.P.M. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.H. reports consultancy at ADC Therapeutics, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, BeiGene, Novartis, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Kite, and TG Therapeutics; and consultancy and research funding at Genentech. Z.M. reports consultancy at Sanofi and Janssen. M.U.M. reports research funding from Iovance Biotherapeutics. S.A. reports consultancy at Incyte and research funding from CSL Behring and Miltenyi Biotec. J.M. reports consultancy at Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Kite, Novartis, AlloVir, Envision, Autolus, Nektar Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics, Caribou Biosciences, Sana Technologies, and Legend Biotech. N.A. reports membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees at BMS and Legend Biotech; and consultancy and research funding at Kite and Gilead. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lauren N. Scott, Department of Hematologic Malignancies and Cellular Therapeutics, University of Kansas Cancer Center, 2060 W 39th Ave, Kansas City, KS 66103; email: Lscott11@kumc.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented as an oral abstract at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

Data are available from the corresponding author, Lauren Scott (Lscott11@kumc.edu), on request.