Acute myeloid leukemia in older populations remains a vexing clinical problem. The incidence of AML dramatically increases after the age of 55.1 Given the shift in demographics in Western populations, this bodes for many more cases of elderly individuals presenting with AML. Unfortunately, the sobering fact is that we still have no effective therapy.

The median survival for older patients with AML is far less than a year and worsens continuously with advancing age to as low as one month for those > age 85.2 The obstacles to effective therapy in older patients include their heightened susceptibility to regimen-related toxicity and their lower response to chemotherapy. This is, in part, due to the higher frequency of "high-risk "cytogenetic lesions in older individuals.3 Even for those elderly patients able to tolerate induction chemotherapy, complete remission rates are well less than half the rate of younger adults (~25 percent in >70 year olds compared to ~70 percent for <50 year olds).4 Also, many cases of elderly AML undoubtedly arise from MDS, so there are few normal stem cells available for hematologic recovery after chemotherapy. As a result complications, hospitalizations, and deaths from cytopenias are common.

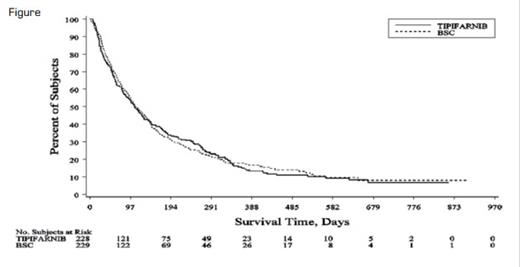

Kaplan-Meier Plot of the Overall Survival for the BSC and Tipifarnib Groups. From Harousseau JL, Martinelli G, Jedrzejczak WW, et al. Blood. 2009;114:1166-73.

Kaplan-Meier Plot of the Overall Survival for the BSC and Tipifarnib Groups. From Harousseau JL, Martinelli G, Jedrzejczak WW, et al. Blood. 2009;114:1166-73.

Over the past decades, many opponents have taken their shot at beating elderly AML ("differentiation" therapy with low-dose Ara-c, conjugated antibody therapy, etc.), but AML has refused to take a fall. The newest challenger is the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib. This drug inhibits protein processing (farnesylation) for signal transduction and was first introduced to AML as a potential inhibitor of RAS; initial trials were somewhat promising, although the effect of the drug was probably against other farnesylated proteins, not RAS. None of the responders in the first trial had RAS mutations.5 This was not entirely surprising, since in AML n-RAS is the predominant mutated RAS, and it largely undergoes modification with a geranyl lipid moiety, rather than farnesylation. In a phase II trial in high-risk and elderly AML, tipifarnib achieved a complete remission (CR) rate of 14 percent.6 Perhaps elderly AML had finally met a worthy match.

A recent phase III trial pitted first-line tipifarnib therapy against best supportive care (BSC), which included transfusion support and hydroxyurea as warranted. The study was quite sizeable, enrolling 457 newly diagnosed elderly (>70 years old) AML patients. The study was conducted around the globe by the optimistically titled "FIGHT-AML-301" consortium.

Unfortunately, the challenger lacked a knockout punch. Comparing the tipifarnib and BSC groups, there were no differences in CR rate, median survival, or overall survival. Tipifarnib produced a low 8 percent CR rate, and while there were no CR cases in the BSC group, this was not reflected in any differences in median survival (107 days vs. 109 days). The overall survival curves (Figure) between the two arms are remarkably (and depressingly) similar. Sadly, it is hard to wring good news from this large, complex study.

In Brief

So, we pick ourselves up from the mat, and do what? One potential strategy is to be clever and outwit this opponent. Biologic studies (the usual assault of the "-omics") might reveal some new pathways that might be exploited by "targeted" therapy. Understanding what happens to normal stem cells — and why they seemingly are easier to transform into AML with age — may offer some preventive strategies. Unfortunately, until some major inroads or insights prevail against elderly AML, it is better not to step into the ring with this one.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Radich indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.