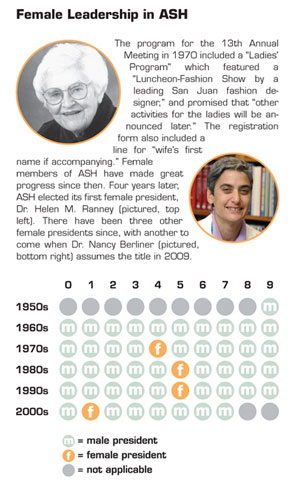

As ASH prepares to mark its 50th anniversary, in a mood of introspection and optimism I’d like to examine where we’ve been and where we are as women in the field of hematology. The most recent ASH statistics show that 26 percent of ASH members are women. In the last 50 years, there have been four female ASH presidents, making up approximately 10 percent of these leaders in our field.

Looking around at the other fellows in my program and on the ASH Trainee Council, such numbers do not seem representative. A random sampling of fellowship programs represented on the Trainee Council shows that in some of the largest and most prestigious programs, women are catching up with and overtaking their male counterparts in numbers. At the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the incoming class of 2006 had 10 women and four men as compared to an even seven and seven in 2000 and five men and three women in 1990. At the University of Michigan, the incoming class of 2006 had eight women and seven men. In 2000, there were seven men and six women and, in 1990, six men and two women. Participants in ASH’s Clinical Research Training Institute over the past five years total 80 and include 46 (57 percent) female fellows and junior faculty. There are women represented on every ASH standing committee, making up a range of 17-50 percent of each committee, and chairing four out of 12. And that speaks only of numbers. Clearly, women hematologists are a growing and formidable force.

Historically, women have made an impact on hematology not through sheer numbers, but through drive, intelligence, and compassion. A review of the National Library of Medicine’s exhibition on Women in Medicine highlights some of our most impressive and inspiring female hematologists. Helen Ranney, born in 1920, was not just a landmark researcher in the field of sickle cell anemia, but also the first woman president of the Association of American Physicians and the first woman to chair the department of medicine at the University of San Diego. Incidentally, she served as ASH president in 1974. Jane Desforges, born in 1921, also served as ASH president (in 1985) in addition to serving as the Associate Editor of the New England Journal of Medicine from 1960-1993.

The climate today was built upon the fortitude of female hematologists like Drs. Ranney and Desforges and is nurtured by a growing group of women that make contributions to basic and translational science while simultaneously providing trainees with academic mentorship and life lessons. Dr. Margaret Ragni, Professor of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and an ASH member since 1985, has served on several standing committees for ASH and co-chaired this year’s special symposium at the annual meeting highlighting hematologic problems in women. It was one of the most well attended sessions at the annual meeting.

Dr. Ragni tells me that she has always approached her academic career as a level playing field, feeling that she has just as much to give as the man or woman next to her. Her advice to trainees is not to believe in the word no, instead to persevere toward your goal. She advises, “Don’t focus on perceived inadequacies and insecurities; everyone has them. Even if you feel like you’re not good enough, act like you are.”

In terms of generalizations, real or imagined, of women being more sensitive or taking work personally, her advice is both wise and practical. She says, “Learn to act and present yourself professionally, learn to manage stress and not get flustered.” Her overriding advice in facing obstacles is to humanize those that you disagree with; working toward common goals becomes easy when you make adversaries into friends.

Barbara Alving, Director of the National Center for Research Resources at the NIH, has a c.v. that is as impressive as it is diverse. In addition to co-holding two patents, editing three books, and publishing over 100 papers in the field of thrombosis and hemostasis, she has worked for the FDA and as a member of the hematology subcommittee at ABIM, and serves as Professor of Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda.

Dr. Alving feels that she is constantly in the state of becoming and evolving. Her flexibility and intellectual curiosity, characteristics she feels are integral to personal and academic success, help propel her forward in her endeavors. Her advice to trainees is to “never burn bridges; instead build networks” and she notes that women have particular communication and socializing skills that move projects and collaborations along. She warns against crumbling in the face of rejection and urges women in the field to “pick yourself up, keep showing up, and keep publishing papers.” Dr. Alving is clear that the challenges and stresses of family have an impact on women in hematology. She stresses the importance of nurturing a strong family; in order to do this, she advises women to think strategically about their time commitments, to obtain help with tasks not essential to their careers and family lives, and to always provide time for themselves.

So the question remains: women in hematology — where are we today? Our numbers and presence are growing and we are finding ways into leadership positions. We look for advice from those who went before us and work to encourage and mentor those who follow behind us. We think and feel deeply — about our patients, our research, and our families. In the end, we continue to evolve and adapt to a new world where we still struggle to have it all.