The CANPEDS trial enrolled 1126 patients with suspected pulmonary embolisms. Erythrocyte agglutination D-dimer tests were normal in 456 of these patients. Using a common risk-assessment score, 373 of the D-dimer negative patients were considered to have a low clinical probability of a pulmonary embolism. The subjects were randomized to undergo no further testing or undergo additional diagnostic testing such as lung scans, serial ultrasonography, or pulmonary angiography. The incidence of a pulmonary embolism was extremely low and not significantly different between the two randomized groups. The CANPEDS also analyzed whether D-dimer testing was useful in patients considered to have moderate or high clinical probability of a pulmonary embolism, but accrual of these subjects was too small to make any definitive conclusions.

Without the assistance of good old-fashioned horse sense by a physician, no single diagnostic test can effectively diagnose or exclude the possibility of a pulmonary embolism. Although CT technology is improving, it is better at “ruling-in” a pulmonary embolism than definitively excluding one. In contrast, D-dimer levels are better at “ruling-out” a pulmonary embolism than they are at clinching the diagnosis. Thus the physician must first determine the clinical probability of this diagnosis before actually choosing the most appropriate diagnostic test. Since only 10-25 percent of patients considered to potentially have a pulmonary embolism actually have one, it would be useful to find a way to quickly dismiss this possibility in a large proportion of patients.

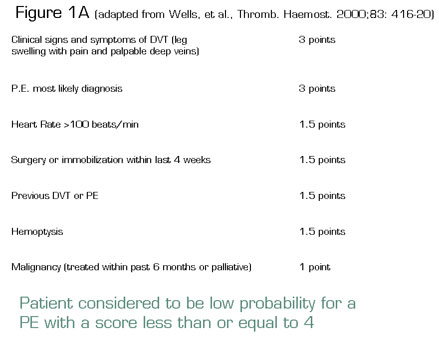

Wells and colleagues proposed a method to divide patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups1 . A simplified version is shown in Figure 1A. Over time, several investigators proposed that merely dividing patients into low-risk (score 4 or less) or high-risk categories is sufficient. Although risk assessment methods such as these are helpful, they still heavily depend on clinical acumen to determine whether a deep venous thrombosis is likely, and whether a diagnosis other than pulmonary embolism is also probable.

In Brief

The D-dimer assay has been proposed as the ideal complement to the physician’s clinical assessment. D-dimers are one type of degradation product of polymerized fibrin and are elevated in the plasma of the majority of patients with deep venous thrombi or pulmonary embolisms. It has been proposed, but never previously demonstrated in a randomized trial, that patients with a low clinical suspicion of a pulmonary embolism and a normal D-dimer do not need additional testing to exclude this disease.

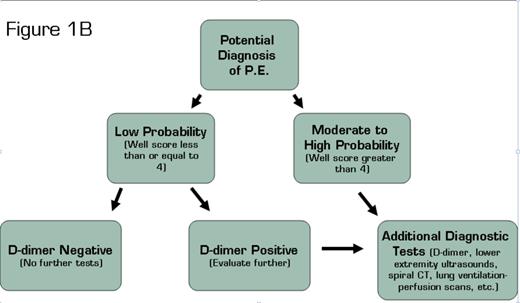

The results of the trial by CANPEDS group were predictable, and therefore reassuring. At last there is Level 1 evidence that clinicians can stop evaluating patients for a pulmonary embolism if the clinical suspicion is low and the D-dimer is normal. This is applicable to the approximately two-thirds of patients who are thought to be in the low-risk category for pulmonary embolisms. Regardless of the D-dimer, the moderate- and high-risk patients will still need additional testing with CT scans or low extremity Doppler studies. This approach is outlined in Figure 1B. However, despite the utility of D-dimer testing, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism still relies heavily on the clinical acumen and “horse sense” of the treating physician.

In Brief

The results of the trial by CANPEDS group were predictable, and therefore reassuring. At last there is Level 1 evidence that clinicians can stop evaluating patients for a pulmonary embolism if the clinical suspicion is low and the D-dimer is normal. This is applicable to the approximately two-thirds of patients who are thought to be in the low-risk category for pulmonary embolisms. Regardless of the D-dimer, the moderate- and high-risk patients will still need additional testing with CT scans or low extremity Doppler studies. This approach is outlined in Figure 1B. However, despite the utility of D-dimer testing, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism still relies heavily on the clinical acumen and “horse sense” of the treating physician.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Abrams indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.