Hemoglobin SC (HbSC) is the second-most common form of sickle cell disease (SCD), comprising 30% of the SCD population in the U.S.,1 yet it remains chronically understudied, with limited therapeutic options.2 Although the clinical phenotype of HbSC disease is on average “less severe” than the more common sickle cell anemia (SCA; HbSS / HbSβ0 thalassemia genotypes), severity can vary substantially. Further, HbSC is associated with complications including retinopathy, osteonecrosis, venous thromboembolism, chronic pain, and early mortality.3,4 Yet, despite HbSC’s well-known degree of morbidity, people living with the disease have been largely excluded or underrepresented in therapeutic SCD trials due to average higher-baseline hemoglobin (a key exclusion for many SCD therapeutic trials for safety), fewer pain episodes, and lower health care utilization. Consequently, guidelines are unable to offer robust evidence-based recommendations on disease-modifying therapy for HbSC, subjecting patients to uneven care.5

Hydroxyurea, the first pharmacologic therapy approved for SCD by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration in 1998, remains the mainstay treatment after almost three decades.6,7 It produces multiple protective physiologic effects, including induction of fetal hemoglobin (which inhibits hemoglobin S polymerization and hemolysis), reduced inflammation, and improved erythrocyte rheology.8,9 In clinical and long-term observational trials for SCA, hydroxyurea was found to reduce the frequency of pain episodes, acute chest syndrome, blood transfusion, and, most importantly, mortality.6,10,11 But despite its demonstrated benefits in SCA, it had not been studied in a controlled trial for HbSC prior to the Prospective Identification of Variables as Outcomes for Treatment (PIVOT) trial.

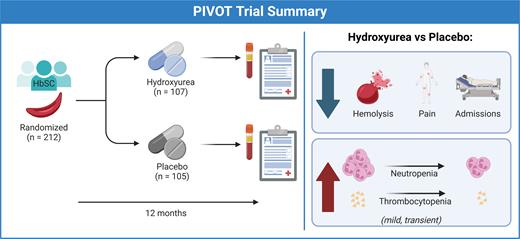

In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority study, Yvonne A. Dei-Adomakoh, MBBS, and colleagues examined the safety of hydroxyurea in 212 people aged 5 to 50 (112 children and 100 adults) with HbSC in Ghana. Participants were followed for a goal of 12 months, receiving placebo or hydroxyurea at 20 mg/kg body weight, with possible dose escalations at months 2 and 4 based on blood counts. The primary outcome was hematologic dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs); secondary endpoints included rates of vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs) and acute chest syndrome.

Individuals who received hydroxyurea had higher rates of DLTs (33%) compared to those receiving placebo (11%). In the hydroxyurea group, DLTs occurred in 20% of pediatric participants and 47% of adult participants, with the most common DLTs being thrombocytopenia or neutropenia. The 22-percentage-point difference in DLTs did not meet the trial’s prespecified 15-percentage-point noninferiority margin. However, the authors note that most DLTs were mild, transient, and asymptomatic, with the rate lower than that observed in trials of hydroxyurea for SCA. Further, they suggest that lower initial dosing among adults could improve the safety of hydroxyurea in HbSC.

Although the trial’s non-inferiority threshold for safety was not met, there was a marked reduction in SCD-related events. Clinical adverse events were 30% less frequent among participants receiving hydroxyurea compared to those on placebo. VOEs were 62% less frequent in the hydroxyurea group, with a corresponding 58% reduction in hospitalizations. There were few acute chest syndrome events in both groups. As expected, the hydroxyurea group had higher mean corpuscular volume, modest fetal hemoglobin induction to 10% (compared to 3% for placebo), lower reticulocytes and other blood counts, and decreased blood viscosity. Interestingly, higher fetal hemoglobin at month 12 was not associated with fewer VOEs, suggesting other unknown pathways leading to the reduction in pain events.

This trial serves as welcome news to the sickle cell community, as providers have had frustratingly little to offer this substantial patient population for far too long.12 Some questions linger: Will the benefits generalize to the HbSC population in higher-income countries, especially considering a higher incidence of chronic pain and greater access to preventive and supportive care? How does hydroxyurea help in HbSC, outside of fetal hemoglobin induction? And most importantly, which individuals with HbSC benefit from long-term hydroxyurea? The authors of the PIVOT trial note there may be debate around the ethics of another placebo-controlled trial, but ultimately more studies are needed to clarify the benefit of hydroxyurea for HbSC, especially in higher-income countries.

In Brief

The PIVOT trial provides the strongest argument yet for the potential benefit of hydroxyurea for HbSC (Figure), bolstering findings from other non-controlled trials that have demonstrated benefit.13,14 Although the trial was not designed to test the efficacy of hydroxyurea in HbSC, the observed reduction in rates of VOEs was similar to or better than the response reported in SCA clinical trials, suggesting hydroxyurea may have a role in the treatment of HbSC. The DLTs that occurred in this study are known effects of hydroxyurea from extensive experience with its use in SCA, and they are not expected to be a barrier for adoption despite failing to meet the non-inferiority threshold. While many practicing SCD providers will use the PIVOT trial as further evidence to prescribe hydroxyurea for individuals living with HbSC, further controlled trials in higher-income countries are needed to fully understand for whom the benefits of hydroxyurea outweigh the small but notable risks.

Disclosure Statement

Drs. Rivenbark and Wilson indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.