Evidence regarding the impact of donor-associated characteristics on recipient outcomes following red blood cell (RBC) transfusion remains controversial, and the influence of specific characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, and genetic factors on recipient mortality has been poorly defined. Sex-related differences have been reported to affect both red cell physiology and viability during storage,1,2 an increased risk of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) has been observed in recipients of blood transfusions from female donors,3 and an increased risk of mortality has been observed in male recipients of blood transfusions from parous female donors.4 Nonetheless, existing data from observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses paint an unclear picture regarding the impact of donor sex and donor–recipient sex mismatch on patient outcomes.5-7

The Innovative Trial Assessing Donor Sex on Recipient Mortality (iTADS),8 one of the first pragmatic randomized control trials to examine the impact of donor sex on RBC transfusion outcomes, was a multicenter, double-blinded study in which individuals receiving RBC transfusions on either an inpatient or outpatient basis were randomized to receive from either male or female donors. All patients with at least one RBC transfusion order were eligible for randomization by the blood bank, which was performed at a male-to-female ratio of 60:40. Patients receiving emergency release units or with complex RBC antibodies that precluded timely randomization were excluded.

The primary outcome of this study was mortality, calculated from the time of randomization to the end of the trial follow-up period, with the pool of male donors serving as the control group. Secondary outcomes included survival at multiple time points over two years, duration of hospitalization, number of subsequent hospitalizations, ICU admissions, new diagnoses of cancer, new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or C. difficile infection, introduction of hemodialysis, number of myocardial infarctions, and number of RBC transfusions received.

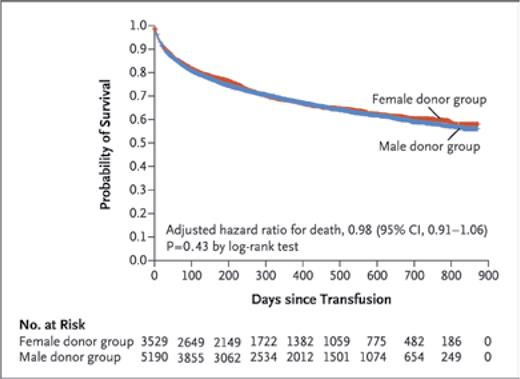

The intention-to-treat analysis included 8,719 patients (3,529 female, 5,190 male) followed up over a mean of 11.2 months. Baseline characteristics in the two groups were similar. In the analysis of the primary outcome (i.e., survival), the unadjusted hazard ratio for death was 0.97 (95% CI 0.9-1.05), while the age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio was 0.98 (95% CI 0.91-1.06) (Figure). Compliance rates for randomization in the female and male donor groups were 90.7% and 86.6%, respectively. An additional analysis including only patients who only had received transfusions from the assigned donor group revealed an unadjusted hazard ratio for death of 0.97 (95% CI 0.89-1.06), suggesting that the intention-to-treat analysis was not limited by the rate of compliance with allocated interventions.

Survival among patients who underwent transfusions (reproduced with permission, Figure 2 in Chasse M et al., N Engl J Med. 2023;388(15):1386-1395).

Survival among patients who underwent transfusions (reproduced with permission, Figure 2 in Chasse M et al., N Engl J Med. 2023;388(15):1386-1395).

The analysis of secondary outcomes revealed no between-group differences, except a higher incidence of MRSA infections in the female group than in the male group, with a hazard ratio of 2.0 (95% CI 1.15-3.46). Interestingly, when sub-analyses were conducted according to donor age, individuals receiving RBC units from female donors between 20 and 29.9 years of age exhibited a higher risk of death (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.93; 95% CI 1.30-6.64). Also of note were the differences observed in cases of donor–recipient sex mismatch. In one subgroup analysis, a slightly lower risk of death (HR = 0.9, 95% CI 0.81-0.99) was observed among male patients receiving units from female donors. However, as the authors speculated, the inconsistencies across subgroups and the multiplicity of analyses suggest that the findings for all secondary outcomes were due to chance.

In Brief

The iTADS is notable given its gold-standard approach and design as a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded study with sufficient power to detect an absolute difference in survival of 2% between recipients of transfusions from the male and female donor groups. Based on this rate, the authors concluded that donor sex did not significantly influence survival among recipients of RBC transfusions. Interestingly, these findings contradict the results of a previous longitudinal study by the same group of investigators,7 which suggested that RBC transfusions from female donors resulted in an 8% increase in recipient mortality in a similar patient population (p<0.001). Notable differences between the studies (e.g., study design and evolving strategies for mitigating TRALI) help explain and support the validity of the iTADS outcomes. However, limitations appropriately described by the authors included non-RBC transfusions that were not restricted to the assigned sex groups and the potential for transfusion recipients to have received RBCs from a donor of a different sex prior to study enrollment, which may have confounded and mitigated potential differences in survival outcomes. Additionally, the decision to focus primarily on the end outcome of survival and not monitor outcomes more proximal to the time of transfusion may have resulted in underestimation of the impact of donor sex on morbidities not captured in the secondary analysis. Future studies should utilize additional outcome measures to identify any potential role of donor sex when matching donors and recipients for RBC transfusions.

Competing Interests

Drs. Su, Shah, and Adamski indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.