Despite increasing ethnic and racial diversity within the United States, diversification of the academic medical workforce continues to lag far behind general U.S. trends. In 2021, 2,562 (11%) self-identified as Black. In 2020, Black scientists earned only 7 percent of all doctoral degrees.1 While the enrollment of Black students in either medical school or doctoral degree programs has increased over time, Black physicians and researchers remain underrepresented in academic medicine across all ranks.2, 3

Unique Challenges Experienced by Black Faculty in Academic Medicine

As Black faculty progress in their academic careers, race and gender differences among those promoted from assistant to associate or full professor and those holding leadership positions (e.g., department chairs or division chiefs) become even more striking.4 For example, between 1979-2013, Black faculty accounted for 5 percent (n=6,011) of all assistant professors at academic medical institutions, yet only 17 percent (n=1,085) of Black assistant professors were promoted to the associate level.3 During the same period, only 24 percent of Black associate professors were promoted to full professors.3 A 2022 publication reporting survey results from the Association of American Cancer Institutes revealed that 2.4 percent of cancer center directors, 1.5 percent of research program leaders, and none of the deputy cancer center directors in the United States were Black.4 These trends demonstrate the attrition rates and the glass ceiling effect experienced by Black faculty across academic medical centers (Figure 1).

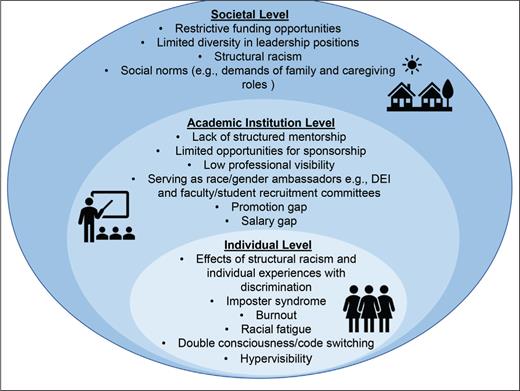

Several factors at multiple levels contribute to the lack of advancement of Black faculty to senior leadership positions and their attrition from academic medicine in pursuit of alternate career pathways. At the individual and interpersonal level, these include the psychological and other harms associated with persistently navigating structural and systemic racism, creating feelings of inadequacy and leading to imposter syndrome.5 At the institutional level, Black faculty struggle to find quality mentors sufficiently invested in their careers and overall development, further limiting their ability to advance into leadership roles.6 Finally, at the societal level, restrictive funding makes it even more challenging for Black faculty to gain the support needed to build successful independent research careers (Figure 2).7

Strategies to Enhance the Retention of Black Women in Academic Medicine

While an emphasis has traditionally been placed on increasing the recruitment of medical and graduate students historically under-represented in medicine, the focus has seldom been on developing programs and resources to support the career advancement of Black faculty and limit their attrition from academia.

Federally funded mentoring programs

In response to the need to support faculty from under-represented racial/ethnic groups in academia, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) has funded the Programs to Increase Diversity Among Individuals Engaged in Health-Related Research (PRIDE) since 2006.8 PRIDE includes nine sites across the United States, each focused on a different area of research on heart, lung, blood, and sleep disorders. PRIDE mentees enroll in a one-year program, which includes a summer intensive focused on professional development activities, peer mentoring, research and scientific writing, laboratory techniques, and leadership skills. Mentees also benefit from extended mentorship from a senior mentor with a successful independent research program. Some PRIDE programs, for example Functional and Translational Genomics of Blood Disorders (PRIDE-FTG; grant no., 5R25HL106365-13; principal investigator, Betty Pace), provide mentees (including coauthors Dr. Oyedeji [cohort 9] and Dr. Grant [cohort 10]) with opportunities to compete for pilot grant funds from NHLBI and serve as a bridge to securing extramural funding.8 For instance, 64 percent of PRIDE-FTG mentees have successfully competed for and received federal funding.8, 9 Furthermore, PRIDE FTG has trained 102 early-career investigators from 50 U.S. institutions, with 70 percent women and most identifying as Black.

The PRIDE program exemplifies how dedicated mentorship and financial resources within a supportive environment can drive innovation and change and in turn enhance diversity among faculty.

Grassroots mentorship efforts to support Black women in academic medicine

Black faculty are tasked with navigating individual and systemic racism, institutional exploitation, and increased mental and financial challenges, further exacerbating the toll of burnout.10, 11 Thus, Black faculty are leaving academia at alarming rates.12-14 These reports suggest a critical need for efforts to slow attrition.12 Peer mentoring is critical to helping Black faculty survive and thrive in academia; these grassroots efforts often provide a safe space for faculty with shared experiences to discuss and navigate challenges while fostering a sense of community.15 Such efforts can increase career satisfaction, faculty retention, and research productivity, leading to academic promotion.16 Now more than ever, Black faculty, especially women, need these support systems to slow their attrition from academia (Figure 1).17 Recognizing these benefits, in 2021, coauthors Drs. Oyedeji and Grant launched the Black Women in Science Empowering and Reaching (BWiSER) peer mentoring program during their first year as faculty. Unlike some existing programs, BWiSER uses a “reach-back model,” allowing early-career faculty to engage in bidirectional mentoring with resident and fellow physician trainees focused on developing careers in hematology or oncology, who in turn “pay it forward” by mentoring and offering support to junior trainees. Through this informal program, we have created a sense of community and a safe space to share career and research advice, provide social support, form accountability, and provide tips for navigating micro- and macro aggressions within academic institutions.

Mentoring Programs Need to Be Developed Earlier in the Academic Medicine Pipeline

Challenges for Black men and women begin as early as elementary school (grades 1-6), creating disadvantages that can impede their long-term academic progress. Therefore, mentoring and exposure to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields should be introduced from elementary school and supported through the faculty level as a mitigation strategy against faculty attrition.18 The successful implementation of such programs requires human and economic capital and institutional commitment to prioritizing efforts focused on diversifying faculty in academia. Dedicated funding from the National Institutes of Health to develop and implement programs such as PRIDE and the Youth Enjoy Science Research Program can have a sustainable impact on diversity in academic medicine at all levels. However, restrictive applicant eligibility criteria limit the pool of potential applicants to those at the associate professor level and above. Given the attrition of Black faculty as they advance in rank from assistant to associate to full professor in academic medicine, funding to develop such programs remains unattainable for those at the assistant professor level, who freely dedicate their time and effort to mentor the next generation of faculty from underrepresented backgrounds.

In summary, Black faculty, especially Black women, are leaving academic medicine at alarming rates. Strategic and organized mentorship programs that are well-resourced are needed. To slow the attrition of Black faculty, we contend that there is a need to: 1) acknowledge systemic racism and implicit bias and their detrimental impact; 2) fund high-quality mentorship and career development programs geared toward increasing diversity and retention in academic medicine; 3) make funding opportunities available to early-career faculty to develop such programs; and 4) recognize the importance of exposure to high quality mentoring as early as possible to help overcome a lifetime of disadvantage.

Author Note: The authors acknowledge Dr. Betty Pace for her editorial review and Lauren Bates and Jiona Mills for their illustrative contributions.

Competing Interests

Dr. Grant, Dr. Oyedeji, and Dr. Gilmore indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.