Read Part 1 of this Ask the Hematologist online.

The Cases

Case 1

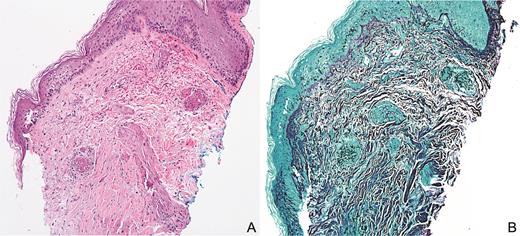

A 50-year-old woman with a history of triple-positive breast cancer and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) following allogeneic transplantation with relapsed and refractory disease was admitted to the hospital for a clinical trial. Dermatology was consulted for a new widespread cutaneous eruption that developed a few days prior to admission and progressed during hospitalization. Vital signs were stable. Physical examination demonstrated mildly tender, edematous, bright pink papules asymmetrically scattered on the face, neck, trunk, and upper extremities (Figure 1). Histopathology from skin biopsy revealed angioinvasive hyalohyphomycotic fungal infection (Figure 2), and tissue cultures and blood cultures grew Fusarium spp. The patient was diagnosed with disseminated Fusarium infection and was treated with voriconazole and amphotericin but eventually succumbed to her disease after 16 days.

Edematous, bright pink papulovesicles scattered on the upper extremities (A) and neck and upper chest (B).

Edematous, bright pink papulovesicles scattered on the upper extremities (A) and neck and upper chest (B).

(A) Septated nonpigmented hyphae centered around blood vessels and extending into surrounding tissue with extravasated red blood cells with minimal associated inflammatory infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×). (B) Grocott methenamine silver stain highlights fungal organisms (10×).

(A) Septated nonpigmented hyphae centered around blood vessels and extending into surrounding tissue with extravasated red blood cells with minimal associated inflammatory infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×). (B) Grocott methenamine silver stain highlights fungal organisms (10×).

Case 2

A 67-year-old woman with a history of AML status following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (SCT) was admitted for community acquired pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for a new painful cutaneous eruption affecting the right arm that then spread to involve the trunk and face. Vital signs were stable. Physical examination revealed multiple clusters of monomorphic vesicles on the right upper extremity, scattered vesicles on the trunk and left upper extremity, and crusted erosions on the face (Figure 3). Viral swab from an unroofed vesicle was positive for varicella zoster virus (VZV) DNA. Ophthalmologic examination revealed no ocular complications. The patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes zoster and was treated with acyclovir. Her lesions continued to progress despite treatment, and given concern for acyclovir-resistant disease, therapy was switched to foscarnet with resolution.

Case 3

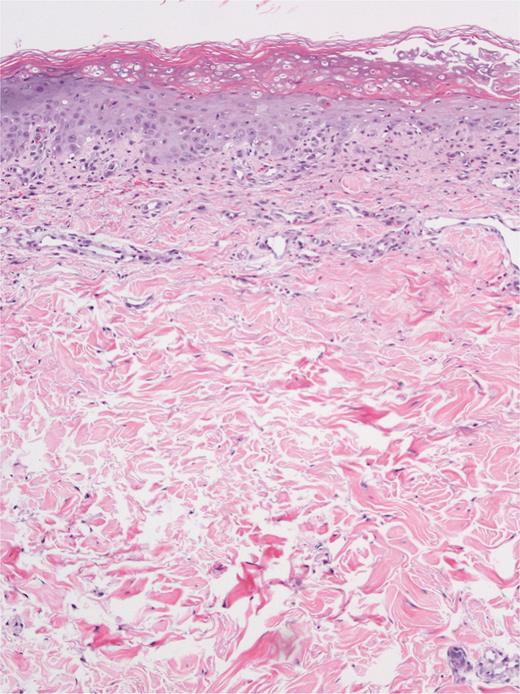

A 64-year-old woman with a history of B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia was admitted for fludarabine/busulfan conditioning followed by allogeneic peripheral blood SCT. Dermatology was consulted for a new asymptomatic cutaneous eruption affecting the trunk. Vital signs were stable. Physical examination demonstrated pink to purple, edematous papules with variable erosion and ulceration scattered on the chest, inframammary folds, and abdominal folds (Figure 4). Histopathology from skin biopsy revealed epidermal dysmaturation with underlying mild interface dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 5). The patient was diagnosed with toxic erythema of chemotherapy. Skin lesions resolved over several days without any directed therapy.

Pink to purple, edematous papulovesicles with variable erosion and ulceration concentrated in the inframammary and abdominal folds.

Pink to purple, edematous papulovesicles with variable erosion and ulceration concentrated in the inframammary and abdominal folds.

Epidermal dysmaturation with superficial and focal interface dermatitis composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×).

Epidermal dysmaturation with superficial and focal interface dermatitis composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×).

The Question

What is your approach to the diagnosis and management of these papulovesicular eruptions in patients with hematologic malignancies?

The Responses

Case 1

Angioinvasive fungal infections are becoming increasingly prevalent in patients with hematologic malignancies. Although these infections rarely cause clinically significant disease in the immunocompetent, they have the potential to result in fatal disease in the immunocompromised. Causative organisms are ubiquitous in the environment and most commonly include Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., Mucormycetes, and Fusarium spp., among others. An immunosuppressed state is the primary risk factor for developing an angioinvasive fungal infection.1,2 In the case of Fusarium spp., the main portal of entry is via inhalation or trauma to the skin or mucous membranes. Cutaneous findings include erythematous papules, nodules, or plaques with a variable degree of necrosis, hemorrhagic ecthyma gangrenosum–like lesions, target lesions, or deep subcutaneous nodules. Skin involvement may represent primary infection or disseminated disease, which can involve any site and rapidly progress over a few days.3

Diagnostic steps include sterile punch biopsy, fungal tissue culture, and fungal blood cultures, followed by appropriate imaging to identify the extent of other organ involvement. Histopathology can identify fungal organisms based on morphologic features such as septation and pigmentation; however, tissue and blood cultures are necessary to speciate pathogens and provide treatment susceptibilities. First-line and second-line antifungal therapy include intravenous amphotericin and intravenous voriconazole, respectively, and a combination of the two is frequently used to treat disseminated fusariosis.4 Widespread disease in immunocompromised patients portends a poor prognosis; therefore, prompt diagnosis and empiric therapy are essential to prevent morbidity and mortality in this patient population.

Case 2

Herpes zoster results from the reactivation of latent VZV. Primary risk factors include advanced age and immunosuppression. Clinical presentation typically begins with an acute prodrome of burning pain or paresthesias in the affected dermatome followed by the development of erythematous papules, vesicles, or pustules in the same dermatomal distribution. Immunosuppressed patients may have an atypical appearance with hyperkeratotic, ulcerated, or necrotic lesions that can be nondermatomal, multidermatomal, or disseminated. These patients carry a higher risk of complications including postherpetic neuralgia, ocular or optic complications, encephalitis, and recurrent disease.5,6 In immunosuppressed patients, herpes zoster is most prevalent in those who have undergone hematopoietic SCT and have cancer, and complications are more prevalent in hematologic malignancies than solid tumor malignancies.7,8

Diagnosis is primarily based on history and clinical appearance; however, further testing including Tzanck smear and polymerase chain reaction testing can be useful for atypical presentations or immunocompromised patients with disseminated disease. Treatment for localized disease includes oral valacyclovir, famciclovir, or acyclovir, while intravenous acyclovir is indicated for disseminated disease, ophthalmic involvement, or in severely immunosuppressed patients. If there is concern for acyclovir-resistance, which is rare but more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients, alternative therapies such as foscarnet or cidofovir can be used.9 Early initiation of appropriate antiviral therapy along with analgesics is important in reducing the incidence and severity of acute zoster-related pain along with other complications.

In immunocompromised transplant patients, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended to prevent VZV reactivation, though there is no current standardized regimen. Clinical trials investigating the available zoster vaccines in immunosuppressed patients have demonstrated that the inactivated recombinant varicella vaccine is safe, immunogenic, and efficacious in autologous hematologic SCT patients and solid organ malignancies, but not effective in hematologic malignancies.10-12 Newer data suggest that the live zoster vaccine is safe and immunogenic in hematologic SCT patients if given two years after transplantation.13

Case 3

Chemotherapeutic drugs are an increasingly common source of injury to the skin, and various reaction patterns exist depending on the type of drug involved. These cutaneous reactions present with variable clinical and histologic overlap; therefore, the diagnosis of “toxic erythema of chemotherapy” is often used as an all-encompassing term for nonallergic, noninfectious skin reactions to chemotherapy. The most implicated agents include anthracyclines, cytarabine, and other antimetabolites.14 Cutaneous reactions are thought to be related to the excretion of cytotoxic chemotherapy agents via eccrine sweat ducts, which yields a direct toxic insult to the local eccrine duct, acrosyringium, and epidermis. Areas with high concentrations of eccrine ducts, such as acral sites, as well as areas prone to sweat trapping such as intertriginous sites, are prone to developing these types of reactions.

Clinical findings include erythema and edema involving the hands, feet, and intertriginous zones, with associated pain, burning, and paresthesias that develop two days to three weeks after the administration of the offending chemotherapeutic agent. Recurrence may occur and worsen on rechallenge. Histopathologic features include keratinocyte atypia, epidermal dysmaturation, epidermal vacuolar degeneration, dermal edema, and eccrine squamous syringometaplasia. Toxic erythema of chemotherapy is self-limited and will spontaneously resolve with desquamation. Therapy is primarily directed at symptoms and includes emollients, analgesics, cool compresses, topical corticosteroids, and topical antibiotics for any erosions. It is not necessary to discontinue the offending chemotherapeutic agent; however, reduction in dosing and frequency may reduce severity and recurrence.15,16 Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease) has also been described in the setting of chemotherapy. This presentation may be considered a variant of toxic erythema of chemotherapy as there is considerable clinical and histopathologic overlap as well as a similar therapeutic approach as outlined previously.17–19

Conclusion

Many dermatologic conditions can present with papulovesicular eruptions and may be difficult to distinguish clinically, especially in the immunosuppressed patient. These not only include angioinvasive fungal infections, herpes zoster, and toxic erythema of chemotherapy, but also neutrophilic dermatoses, cutaneous metastases, leukemia cutis, and others. Early dermatologic consultation and multidisciplinary care are essential for prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment to prevent the high morbidity and mortality associated with these conditions and to improve patient outcomes.

Competing Interests

Dr. Popatia and Dr. Wanat indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.