Increasingly, image-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy (CNB) and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) are used to evaluate lymphadenopathy and other radiographic lesions - a change in practice from the use of excisional biopsies. The literature is full of single-institution reports touting the efficacy of diagnoses based on limited samples obtained from FNAC/CNB. The advantages of limited sampling approaches compared to a surgical biopsy seem obvious: They are easier to schedule, more cost effective, relatively noninvasive, and relatively low morbidity, all aligning with patient and provider preferences. These minimal sampling approaches, however, often comprise just a few cubic millimeters of tissue or a few thousand disaggregated cells. Are these tiny specimens good enough to support perhaps the most important treatment decision in a patient's life? At our center, we have found that in patients with anterior mediastinal masses specifically, limited tissue sampling can be insufficient for an accurate diagnosis.

In both community hospitals and large academic medical centers, FNAC/CNB has become the primary diagnostic procedure for patients with an anterior mediastinal mass. Anterior mediastinal masses are uncommon. The differential diagnosis is broad, including both carcinomas (thyroid, mediastinal germ cell tumor, thymic carcinoma) and hematologic malignancies, particularly lymphomas, from Hodgkin to many types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [not otherwise specified], precursor T- or B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, and gray zone lymphoma). Diagnosis requires microscopy and often other methods, including flow cytometry; immunohistochemistry; and fluorescence in situ hybridization, karyotype analysis, and even next-generation sequencing. Precise classification is critical because each of these diseases has distinct and often entirely non-overlapping therapies administered with curative intent. Given the vital structures in the mediastinum, a rapidly growing tumor in this space may lead to life-threatening respiratory and circulatory emergencies, necessitating a timely and accurate diagnosis.

Publications about failures, specifically misdiagnoses resulting from minimal sampling approaches, are perhaps nonexistent. Without that data, it is unclear whether there are patients for whom a surgical biopsy should be the first consideration. In this article, we present vignettes of three patients with mediastinal masses - with some slight modifications of history to avoid identification of patients, providers, and institutions - who we believe would have benefited from an excisional biopsy rather than FNAC/CNB as the initial diagnostic procedure. To make the point that we are not merely quibbling about common issues (e.g., “Is it gray zone lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma?”), our featured cases involve circumstances where the differential diagnosis involved thymoma and lymphoma. Because we could find no publications about misdiagnoses using FNAC/CNB, our article reviews the limited literature about the adequacy of these techniques, under the premise that the rate of inadequacy (the inability to fully classify a tumor based on this sampling) is related to the risk of misdiagnosis based on minimal sampling.

The Question

Are computed tomography (CT)-guided CNBs optimal as the first approach for the diagnosis of a mediastinal mass?

The Cases

Case 1. A 61-year-old man was referred for evaluation of T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LLy). Four months before presenting to the clinic, he was admitted to an outside hospital with acute hypoxic respiratory failure due to b/l pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation, progressive fatigue, night sweats, and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lbs. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed precarinal lymphadenopathy (2.9 × 1.9 cm) and a mediastinal mass (3.1 × 2.6 cm). A positron emission tomography scan revealed a 3.3 × 2.6 cm mass in the anterior left chest wall adjacent to the sternum with a standardized uptake value of 5.6. FNAC/CNB biopsy of the mass was performed at an outside institution. The FNAC was referred to our institution for flow cytometry. Flow cytometry identified a homogenous-appearing population of immature T cells co-expressing CD4 and CD8; this result was interpreted as consistent with T-LLy, as suggested by the histology report of the CNB performed at an outside institution. The patient was admitted to the inpatient adult leukemia service for treatment. His physical examination was remarkable for a 10 cm well-healed sternotomy scar. Questioning the patient about the sternotomy scar revealed a remote history of a resection of a nonmalignant tumor (“something with a T”). An urgent discussion with hematopathology and review of the CNB specimen led to a recommendation for a surgical consultation and excisional biopsy.

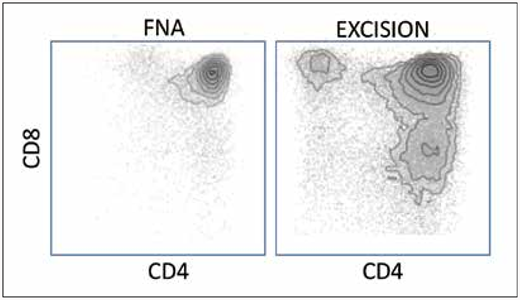

The patient underwent an excisional biopsy of the mediastinal mass the following day. Histology and immunohistochemical staining of the tissue sample demonstrated unequivocal features of thymoma. The more substantial specimen showed clear flow cytometric evidence of T-cell diversification that was not apparent on the smaller, original specimen (Figure 1). Chromosome analysis of the tissue specimen revealed a normal male karyotype. Polymerase chain reaction studies did not reveal a clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma gene. The patient subsequently underwent definitive therapy with a left anterior chest wall resection, including ribs 2 and 3, intercostal muscle pectoralis muscle and skin, and partial sternectomy with a complex reconstruction of the chest wall defect. The diagnosis of the final specimen was thymoma, recurrent (3.7 cm), World Health Organization (WHO) histologic type B1.

Case 1 illustrates that flow cytometry and ancillary tests often cannot compensate for poor or minimal sampling. It is well-established that the specificity of both flow cytometry and molecular methods for detection of clonality depends on the number of cells and fraction of neoplastic cells in a specimen. Here, the flow cytometry of the initial specimen was performed on a few thousand events, resulting in a homogenous appearing population. In contrast, the flow cytometry of the excised specimen with at least 10 times as many cells, shows clear evidence of T-cell maturation, a qualitatively different result that is indicative of a non-neoplastic T-cell population.

Case 1 illustrates that flow cytometry and ancillary tests often cannot compensate for poor or minimal sampling. It is well-established that the specificity of both flow cytometry and molecular methods for detection of clonality depends on the number of cells and fraction of neoplastic cells in a specimen. Here, the flow cytometry of the initial specimen was performed on a few thousand events, resulting in a homogenous appearing population. In contrast, the flow cytometry of the excised specimen with at least 10 times as many cells, shows clear evidence of T-cell maturation, a qualitatively different result that is indicative of a non-neoplastic T-cell population.

Case 2. A 55-year-old woman was referred from another hospital for evaluation of node negative, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor positive invasive ductal carcinoma. Staging radiographic studies suggested a mediastinal mass. FNAC/CNB was performed and the combination of histology with all appropriate immunohistochemical studies as well as flow cytometry showed T-LLy. The marrow was normal with no evidence of T-LLy. The patient received tamoxifen and regional radiation for the breast cancer, and multiple cycles of HyperCVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, doxorubicin hydrochloride, dexamethasone, plus methotrexate and cytarabine) chemotherapy for the T-LLy. After eight years in apparent remission, the patient developed pancytopenia. Imaging studies revealed a recurrent anterior mediastinal mass. An excisional biopsy of the mediastinal mass was performed and revealed thymoma. This diagnosis prompted re-examination of the original CNB, which showed that the original mediastinal mass was also thymoma. A marrow biopsy showed no evidence of T-LLy or metastatic breast cancer to explain the pancytopenia, but rather a therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome that evolved to acute myeloid leukemia within two years.

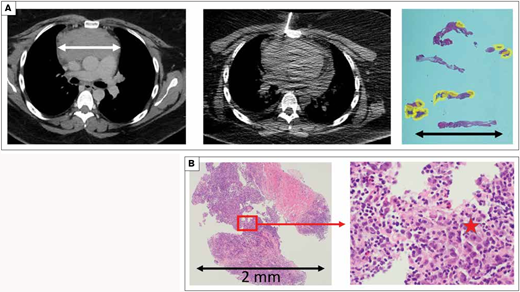

Case 3. A 34-year-old woman presented with dysphagia and odynophagia and associated fevers, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss of 30 lbs. A CT scan of the neck and chest revealed cervical adenopathy (6.5 × 5.2 cm) and an anterior mediastinal mass (11.1 × 4.8 cm). FNAC and four CNBs were obtained from the anterior mediastinal mass. These cores were composed predominantly of fibrous (non-diagnostic) tissue (Figure 2). The lymphocytes were small and benign appearing on histologic review. A diagnosis of thymoma, WHO histologic type B2 was rendered. The thymoma was considered nonresectable and three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were administered. Prior to undergoing definitive surgical resection for the thymoma, the case was re-examined at a tumor board. The original fixed paraffin specimen was sectioned for additional slides to review, and a small number of classic Reed-Sternberg cells were identified on the second review. The tissue originally interpreted as thymoma, most likely represented associated-entrapped hyperplastic thymic tissue. This new interpretation was confirmed by hematopathology, and an amended diagnosis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma was issued. The patient was referred to the adult lymphoma service and initiated on standard frontline chemotherapy treatment.

Case 3 illustrates that even under optimal sampling conditions, the amount of “tumor” obtained may be minimal. A) The computed tomography scan shows a 10 × 8 cm anterior mediastinal mass which appeared to safely and reasonably be approached by either an incisional biopsy or fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy (FNA/CNB). The FNA/CNB sampled what appears to be an appropriate volume of the tumor. However, the tissue sections show that most of the sample was fibrosis; the areas composed of lymphocytes are outlined in yellow. The lymphocytes in these limited areas, amounting to 0.06 cm2 in cross section, were correctly interpreted as non-neoplastic forms. With numerous small lymphocytes in the absence of any evidence of a neoplasm, an experienced pathologist interpreted these findings as a thymoma. On subsequent review, additional levels and studies were obtained specifically because the diagnosis of thymoma was based on the absence of neoplastic findings in an otherwise tiny specimen. Additional hematoxylin and eosin stain levels obtained from the original blocks showed rare, definitive Reed-Sternberg cells. B) Small samples are … sometimes tiny samples. And Reed-Sternberg cells are notoriously rare in Hodgkin lymphoma. Images show the most cellular piece of tissue at its largest is 2 mm. Within the red block are several variant forms of Reed-Sternberg cells, marked with a star in the high-power image.

Case 3 illustrates that even under optimal sampling conditions, the amount of “tumor” obtained may be minimal. A) The computed tomography scan shows a 10 × 8 cm anterior mediastinal mass which appeared to safely and reasonably be approached by either an incisional biopsy or fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy (FNA/CNB). The FNA/CNB sampled what appears to be an appropriate volume of the tumor. However, the tissue sections show that most of the sample was fibrosis; the areas composed of lymphocytes are outlined in yellow. The lymphocytes in these limited areas, amounting to 0.06 cm2 in cross section, were correctly interpreted as non-neoplastic forms. With numerous small lymphocytes in the absence of any evidence of a neoplasm, an experienced pathologist interpreted these findings as a thymoma. On subsequent review, additional levels and studies were obtained specifically because the diagnosis of thymoma was based on the absence of neoplastic findings in an otherwise tiny specimen. Additional hematoxylin and eosin stain levels obtained from the original blocks showed rare, definitive Reed-Sternberg cells. B) Small samples are … sometimes tiny samples. And Reed-Sternberg cells are notoriously rare in Hodgkin lymphoma. Images show the most cellular piece of tissue at its largest is 2 mm. Within the red block are several variant forms of Reed-Sternberg cells, marked with a star in the high-power image.

Our Response

Are these three cases anomalies? We don't believe so. However, while other oncologists and pathologists may have a similar story to tell, we couldn't find publications about transparent misdiagnoses due to limited sampling procedures. Nevertheless, buried amongst the vast number of publications touting the “accuracy” of the FNAC/CNB approach, we highlight three reports that speak to a related question: How often are the results of FNAC/CNB inadequate for diagnosis?

First, we ourselves have previously reviewed all English-language literature regarding the efficacy of FNAC/CNB for subclassifying lymphoma.1 In 42 studies, a median of 30 percent of the samplings were inadequate to allow sufficient subtyping of the lymphoma to provide optimal care. Moreover, the practice of FNAC/CNB for the evaluation of a suspected lymphoma contradicts the current recommendations of the European Society of Medical Oncologists,7,8 the WHO Classification of Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue,9 the British Committee for Standards in Haematology,10 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,11 all of which are explicit regarding the preference for excisional biopsies when pursuing a diagnostic workup for a suspected lymphoid malignancy. For example, the current WHO section on principles of classification of lymphoid malignancies states, ”The classification of lymphoid neoplasms is based on all available information to define disease entities. Having sufficient tissue for this multiparameter approach is critical. Great caution is advised when core needle biopsies are used for the primary diagnosis of lymphoma; fine-needle aspiration is generally inadequate for this purpose.”

Second, a recent meta-analysis of 18 studies with 1,310 patients and 1,345 CNBs explored the accuracy and safety of CT-guided CNB for mediastinal masses.2 Dr. Han Na Lee and colleagues were unable to assess the diagnostic accuracy of thymoma or lymphoma cases in this systematic review. Multivariate metaregression analysis revealed that when a greater percentage of lymphoma specimens were included in a study (>40% vs. <40%), it had a negative influencing effect on the diagnostic yield of CNB. Prior single institution studies have reported that 26 to 44 percent of CNBs of mediastinal masses are non-diagnostic for cases of lymphoma.3-5 Despite the findings and acknowledged limitations of CNB for lymphoma, Dr. Lee and colleagues concluded that CNB was reasonable as the “first diagnostic tool for mediastinal masses, since it is less invasive and safe compared to surgery.2 ” Third, and perhaps most informative in regards to the rate of inadequacy of minimal tissue sampling, is a remarkable study by an interdisciplinary team based in interventional radiology at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC)6 whose goal was to maximize the yield of tissues for clinical trials in patients with already established diagnoses. Dr. Deepak Bhamidipati and colleagues reported that with optimized approaches at MDACC, approximately 15 percent of FNAC/CNB failed to obtain sufficient material to enable precision diagnostic testing. In summary, the rate of inadequacy for diagnosis or molecular tests is substantial even in studies where FNAC/CNB is touted and performed by providers with considerable expertise.

Conclusion

While limited sampling approaches to lesions in the mediastinum seem particularly problematic, we have presented this article from the perspective of the hematopathologist and an oncologist. The thoracic surgeon and interventional radiologist may enjoy a great debate on this topic, as they can certainly share “horror” stories of their own about complicated cases involving mediastinal masses. We recognize that there are clinical scenarios when a surgical procedure can be life-threatening in a patient with massive mediastinal disease and risk of airway and cardiac collapse. We also acknowledge that not all hospitals have dedicated thoracic surgery teams to perform such procedures. That said, these cases underscore that the focus of the intervention should be on the individual patient, the clinical history, and the need to balance risks of surgery with added information from an excisional biopsy. We practitioners all know that failures and misdiagnoses happen; but how often, and to whom? Only by clear-eyed recognition of the instances of failure can we hope to guide our patients to the appropriate diagnostic procedure. In the absence of data, sharing our knowledge of demonstrated failures is the only way we can learn how these minimal sampling approaches ought to be used. Given our review of available cases as well as what we've discovered in reviewing the available literature, best practices would indicate that by asking the hematopathologist upfront whether they have enough tissue to make the diagnosis, a practitioner optimizes the opportunity for a more accurate initial assessment, and potentially superior patient outcomes.

Competing Interests

Dr. O'Dwyer and Dr. Burack indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.