Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is an acquired bleeding disorder caused by neutralizing autoantibodies (inhibitors) against coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) with an incidence of 1.5 cases per million persons per year.1 Most cases occur in older individuals (> 65 years old), of which approximately half have an underlying autoimmune disorder or malignancy; about 1 to 5 percent of cases occur in young females during pregnancy or the postpartum period.1-4

FVIII is a cofactor for FIXa activation of FX; the inhibitor interferes with this cofactor activity thus preventing thrombin generation and a hemorrhagic tendency. Typical clinical presentation is a new onset of bleeding of variable severity in the absence of previous personal or family history of bleeding. Mucocutaneous bleeding is the most common presentation. Unlike with severe congenital hemophilia A, hemarthrosis is rare.1,2,5-7 Infrequently, asymptomatic patients may be detected on abnormal routine screening tests of hemostasis.6,8

Diagnosis

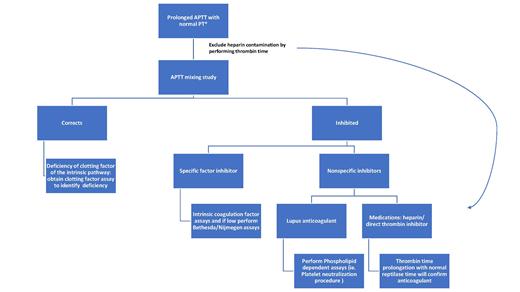

Screening hemostatic assays shows a normal prothrombin time (PT) and thrombin time (TT), as well as a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT; Figure 1). Depending on the sensitivity of the reagents used, APTT typically will be prolonged when FVIII activity (FVIII:C) decreases to 25 to 35 percent of mean normal. Prolongation of the APTT beyond 100 seconds is atypical for FVIII inhibitors and should raise the suspicion for alternative or co-existing causes such as presence of heparin or infrequently a lupus anticoagulant (LA) or deficiency of a coagulation contact factor (e.g., homozygous factor XII deficiency). Mixing studies with an equal volume of normal plasma typically demonstrates immediate inhibition of the APTT. Rarely, with low titer FVIII inhibitors, such inhibition is detectable only after a one- to two-hour incubation at 37°C.9

Evaluation of prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). *Differential diagnosis: 1) deficiency of coagulation factor(s) (e.g., fVIII, IX, XI, XII, prekallikrein, or high-molecular-weight kininogen); 2) heparin contamination of specimen; 3) inhibitor to a specific coagulation factor (e.g.fVIII); 4) presence of a non-specific inhibitor (e.g.. lupus anticoagulant).

Evaluation of prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). *Differential diagnosis: 1) deficiency of coagulation factor(s) (e.g., fVIII, IX, XI, XII, prekallikrein, or high-molecular-weight kininogen); 2) heparin contamination of specimen; 3) inhibitor to a specific coagulation factor (e.g.fVIII); 4) presence of a non-specific inhibitor (e.g.. lupus anticoagulant).

The traditional method of assessing factor VIII inhibitors is the Bethesda assay with Nijmegen modification, which provides the inhibitor titer in Bethesda units (BU).10,11 The Bethesda titer can also be determined using chromogenic assays.12 Alternative methods for detecting autoantibodies include qualitative enzyme linked immunoassays (ELISA), which are based assays that do not quantify the inhibitor titer (Table 1A; available as online supplement).11,13

Management

Principles of management of patients with AHA involves a two-tiered approach of optimizing hemostasis and eradicating the inhibitor.

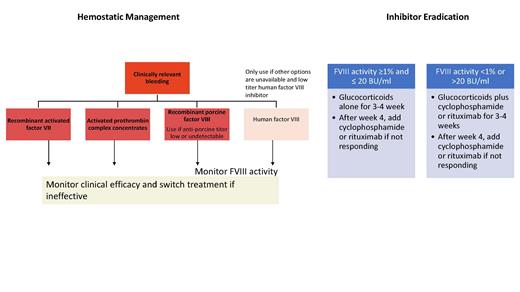

Hemostatic management. Options for hemostatic management include the use of bypassing agents (BPA; activated prothrombin complex concentrates [aPCC] or recombinant FVIIa [rFVIIa]) or recombinant porcine FVIII (rpFVIII: Obizur; Figure 2). There are no data to suggest superiority of one option.14,15 For those without access to BPA or rpFVIII and in patients with low-titer inhibitors (<5 BU), initial therapy with human FVIII (hFVIII) is reasonable.2 This generally results in an increase in inhibitor titer, thus rendering the hFVIII ineffective. However, for patients with high-titer inhibitors (>5 BU), hFVIII is most likely to be ineffective; therefore, every effort to secure BPA or rpFVIII should be made.

Recommendations regarding hemostatic and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with acquired hemophilia A per the 2020 International Recommendations. Adapted with permission from Tiede A et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2020;105(7):1791-1801.

Recommendations regarding hemostatic and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with acquired hemophilia A per the 2020 International Recommendations. Adapted with permission from Tiede A et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2020;105(7):1791-1801.

rpFVIII is effective in AHA due to differences in the A2 and C2 domains of the pFVIII and hFVIII molecule.15,16 The advantage of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved rpFVIII is the ability to measure response to the infused product with FVIII:C. Anti-rpFVIII antibodies may be present for some patients at baseline while some will develop these antibodies after treatment with rpFVIII. The porcine FVIII inhibitor titer should be assessed if rpFVIII is being considered for treatment or if there is a change in treatment response as presence of cross-reacting anti-rpFVIII inhibitors may guide the dose of rpFVIII and identify patients for whom rpFVIII may not be efficacious.2,15

Inhibitor eradication. Options for eradication of the inhibitor with immunosuppressive (IST) therapy include initial use of glucocorticoids with consideration to add adjunctive agents such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab. The goal of IST is to shorten the time to achieve remission in AHA and decrease bleeding. Spontaneous remission may occur though rare.2,17 Prospective data demonstrated that remission was unlikely within 21 days of steroid therapy if FVIII:C is less than 1 percent or the inhibitor titer was more than 20 BU.18 Recent guidelines recommend the use of combination therapy with glucocorticoid and either cyclophosphamide or rituximab in the first-line setting for those with FVIII:C less than 1 percent or high inhibitor titer of more than 20 BU. For other patients, first-line monotherapy with glucocorticoids is sufficient (Figure 2).2

Treatment Monitoring

Hemostatic monitoring. Treatment response is assessed clinically (i.e., control of bleeding) and with laboratory assays for rpFVIII. There are currently no routinely available assays assessing response to BPA (Table 1B; available as online supplement).19,20 If the patient is not responding to treatment with one hemostatic agent, an alternative should be trialed.

Remission. Evidence of eradication of the inhibitor is based on FVIII:C and Bethesda assays. Once remission is achieved, monitoring with FVIII:C should still be performed (monthly for the first 6 months, then every 2-3 months up to 12 months, then every 6 months).2

New Approaches to Treatment

Pending eradication of the inhibitor, patients may experience recurrent hospitalization for bleeding, or some patients may have contraindications to IST. The role of emicizumab, a bispecific FVIII-mimetic antibody, was recently demonstrated for management of AHA.21 In newly diagnosed patients with AHA with contraindication to IST, short-term use of emicizumab and reduced intensity IST led to hemostatic efficacy with BPA discontinuation after 1.5 (1-4) days of emicizumab initiation. Chromogenic FVIII:C was more than 50 percent after median of 115 (67-185) days and emicizumab was discontinued after a median of 31 (15-79) days.21

A caution for FVIII:C monitoring while using emicizumab therapy is that emicizumab falsely elevates the one-stage FVIII:C assay. Chromogenic FVIII:C based on bovine reagents is the optimal assay (Table 2; available as online supplement).19 Additionally, in clinical trials of congenital hemophilia A using emicizumab, use of high doses of APCC (>100 units/kg/day) for management of breakthrough bleeding resulted in thrombotic microangiopathy.22 Therefore, the optimal agent for breakthrough bleeds in this situation is rFVIIa. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these pilot studies and answer many questions regarding duration of therapy and optimal patient with AHA for whom to consider use of emicizumab.

Conclusion

AHA is a potentially life threatening acquired bleeding disorder. Early recognition and initiation of hemostatic therapy and IST has resulted in a reduction in morbidity and mortality. The role of emicizumab is evolving.

Competing Interests

Dr. Sridharan and Dr. Pruthi indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.