Throughout the last century physicians and researchers alike have fallen in love with the complex science of the single nucleotide mutation that causes sickle cell disease (SCD). How can a genetic misspelling so simple result in a disease with such multifaceted pathophysiology? The convoluted interplay between hemoglobin S polymerization, hemolysis-mediated endothelial dysfunction, concerted activation of sterile inflammation with compromised biorheology, and adhesion-mediated vaso-occlusion has demonstrated that SCD is not merely a disease of abnormal hemoglobin quantity and quality. SCD also represents a systemic vasculopathy disorder with multisystem consequences resulting in early organ damage and premature death.1

Unfortunately, despite a robust elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for the clinical manifestations of SCD, there is a wide dichotomy between science and sociology that has positioned SCD as the poster child for health disparities. To this date, individuals who carry the disease, who are mostly of African descent, live in poverty, are often uninsured or underinsured, have the misfortune to require opioids to treat the predicable complications of their disease, and receive substandard as well as uncoordinated and widely inconsistent medical care. Moreover, they are stigmatized and marginalized by our health care system, because despite falling in love with the science that drives the complex SCD pathophysiology, the larger medical community never fell in love with the people who carry the very mutation that aroused their scientific interest. Consequently, advances in our understanding of the epidemiology and discovery of therapeutic strategies to mitigate the acute and chronic multisystem consequences of SCD remain in their infancy compared to other genetic conditions such as cystic fibrosis, which was discovered nearly three decades after SCD.2 This can partly be attributed to a disparity in research funding between these two monogenetic disorders. With less research funding, there is stunted scientific discovery that results in much slower reductions in disability-adjusted life years. A recent report noted that per affected individual, federal research funding was 3.5 times higher, while foundation funding was 75 times higher for cystic fibrosis compared to SCD between 2008 and 2018.2

For decades, the SCD community, composed of patients, advocates, and providers has raised red flags to remind everyone how far behind the benchmark of optimal access to quality and equitable health care for SCD we truly are. The plot of this story is therefore as predictable as it is heartless; the SCD community has fallen into the lowest caste of the medical field.

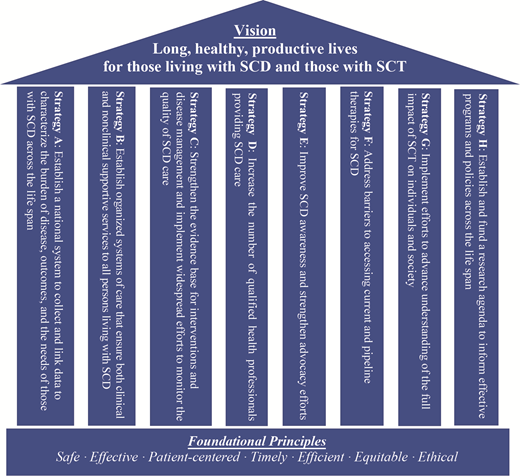

Our 2021 Year's Best for SCD is the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report titled “Addressing SCD: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action,” which has made the vision of our community crystal clear: “Long, healthy, productive lives for those living with SCD and sickle cell trait (SCT) are a fundamental human right no different for SCD than for any other living being.”3 The NASEM report is a blueprint for the construction of this complex vision, as blueprints are by definition, “guides allowing for rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number of copies.” The rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number of functional health care delivery systems for SCD across the globe is our goal.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Minority Health commissioned NASEM to develop a strategic plan for addressing the overwhelming disparities in care experienced by individuals living with SCD. The plan was to include a review of the epidemiology, health outcomes, genetic implications, and societal factors associated with SCD and SCT, including serious complications of SCD such as stroke, kidney and heart problems, acute chest syndrome, and debilitating pain crises. NASEM was also charged with summarizing current guidelines and best practices for the care of patients with SCD and, to the extent possible, defining the economic burden associated with SCD. It outlined current federal, state, and local programs related to SCD and SCT including screening, monitoring and surveillance, treatment and care programs, research, and others. The desired outcome of the report should also provide guidance on priorities for programs, policies, and research, and make recommendations as appropriate. Specific guidance covers: 1) limitations and opportunities for developing national SCD patient registries and/or surveillance systems; 2) barriers in the health care sector associated with SCD and SCT, including access to care and quality of care, workforce development, pain management, and transition from pediatric to adult care; 3) necessary innovations in research, particularly for curative treatments such as gene replacement/gene editing and increasing awareness and enrollment of patients with SCD in clinical trials; and 4) the expanded and optimal role of patient advocacy and community engagement groups.

Within this report are two overarching principles that light the path in our journey to improve health care delivery for patients with SCD. First, we must refine what we know about the disease, its multisystem organ complications, and the biopsychosocial implications. Second, we must elevate and accelerate what we do about it. The report mandates the establishment of national systems to collect and link data to characterize the true burden of SCD. An integral first step to understanding the best course of action is instituting a comprehensive data collection system for patients that will measure the burden of disease, care needs, and eventual outcomes. This would include understanding the full impact of SCT, which is carried by one in 12 African Americans. Reorganization of the crumbling systems of care to ensure that support services that treat the mind, body, and spirit of an individual living with SCD across their lifespan would also be mandated and funded. The emphasis on high-quality, evidence-based, comprehensive primary and subspecialty care delivered by empathetic multidisciplinary teams is currently lacking and must be reinvigorated. We must also proactively address the lack of evidence-based medicine that has plagued SCD care delivery due to the scarcity of existing high-quality research and data on the longitudinal course of the disease beyond childhood. Similarly, the report offers innovative strategies to tackle the shortage of qualified, interested, and empathetic health care professionals who are invested in both seeking the much-needed evidence and providing the robust comprehensive care persons living with SCD need and deserve.

Certainly, advocacy and awareness efforts have trailed behind that of other rare diseases due to lack of funding, government investment, and sociocultural attention, and the report highlights this as a necessary correction to make meaningful progress. Finally, as is known to most hematologists, the toolbox for treating SCD has been barren for many years, and even though new therapies have been recently approved, the report identifies the need for optimizing access and dissemination of these as well as other more traditional therapies. Dedicated researchers have driven the field forward despite all odds, and the report advocates for a tailored research agenda that academicians, sponsors, and advocates can agree with. The NASEM report outlines a comprehensive strategy grounded on eight pillars: advocacy, education, care standardization, policy change, quality improvement, community engagement, longitudinal data collection, and research (Figure). With this clear vision in mind and the understanding that the task before us is a monumental one, all hands will have to be on deck. An approach with multistakeholder involvement and true partnership is a prerequisite for the vision of the NASEM report to be realized. However, the time to do this is now, because while we wait, people with SCD are dying young, every day. We mourn the loss and celebrate the life of two of such champions: Dr Carlton Haywood and Hertz Nazaire.

Reprinted from “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. 2020.” With permission from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academies Press.

Reprinted from “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. 2020.” With permission from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academies Press.

Competing Interests

Dr. Minniti and Dr. Osunkwo indicated no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Zaidi is an employee of Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The opinions and positions expressed here are his own. He has served on advisory boards for and has received honoraria from Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT), Novartis, Emmaus Life Sciences, Cyclerion, bluebird bio, Chiesi, and NovoNordisk; has worked on research and clinical trials for Imara, Forma Therapeutics, and GBT; has served on the GBT Speaker Bureau; and has received funding from Emmaus Life Sciences, GBT, and Novartis.