The management of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is evolving at a rapid rate, particularly in older patients (>65 years) with access to well-tolerated novel combination therapies such as venetoclax combinations or liposomal chemotherapy formulations that lead to high rates of complete remission (CR).1 However, relapse rates remain unacceptably high, and strategies leading to long-term survival remain elusive.

Maintenance treatment with either chemotherapy or targeted small molecules consists of the long-term post-remission administration of less intensive therapy with the goal of prolonging CR and minimizing significant toxicity. Biologically, these therapies aim to suppress and eliminate malignant clones, reducing clonal evolution and consequent treatment resistance. One application of the maintenance approach in AML has been the addition of FLT3 inhibitors to FLT3-mutated AML in CR post–allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Maintenance sorafenib has recently demonstrated improved disease-free and overall survival (OS) in post–allo-HSCT patients with FLT3-mutated AML in CR,2 and results of a large phase III prospective trial of gilteritinib in the post–allo-HSCT setting are awaited (NCT02997202). In patients not eligible for allo-HSCT, maintenance strategies employing combinations of low-dose chemotherapy or immunomodulatory agents have demonstrated some clinical benefit; however, trials have been limited by small sample sizes, suboptimal induction regimens, and lackluster results, limiting their widespread application to date.3 Thus, for elderly patients unfit for HSCT facing inevitable relapse, for whom quality of life and treatment burden are key concerns, low-intensity maintenance therapy to prolong CR represents an important clinical need.

The HOVON97 trial investigated the use of the hypomethylating agent azacitidine (AZA) administered for up to 12 cycles in elderly patients with AML who had achieved CR or CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) following two cycles of intensive chemotherapy.4 Although it was not powered to assess an OS advantage, the trial did demonstrate an improvement in 12-month disease-free survival (DFS), from 42 percent in the control group to 64 percent in patients receiving AZA — a benefit limited to patients with CR or baseline platelet count greater than 100 × 109/L on post-hoc analysis. As a palliative treatment, however, regular subcutaneous AZA is burdensome, requires regular day therapy appointments, and leads to local skin toxicity, which might limit treatment in the maintenance setting.

Dr. Andrew H. Wei and colleagues published the findings of the QUAZAR AML-001 study, a randomized, international, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating oral AZA (CC-486) as maintenance therapy in patients with AML aged 55 years or older, following induction chemotherapy with or without consolidation therapy, who were ineligible for allo-HSCT.5 The authors randomized 472 patients to receive either CC-486 at a dose of 300 mg once daily or placebo for 14 days of a 28-day cycle, repeated continuously until relapse with blasts greater than 15 percent or unacceptable toxicity. Most patients had intermediate-risk cytogenetics (86%) and had received at least one cycle of consolidation chemotherapy (80%), whereas half (46%) had detectable minimal residual disease (MRD). The headline finding was that after a median follow-up of 41.2 months, OS was significantly improved in the CC-486 group compared to placebo (24.7 months vs. 14.8 months; p<0.001), a benefit that was preserved when patients were stratified for age, primary versus secondary disease, cytogenetic risk group, and presence versus absence of prior consolidation therapy. Relapse-free survival was also prolonged. The magnitude of benefit of CC-486 appeared to be increased in patients who were MRD positive and/or had received fewer cycles of consolidation therapy. The therapy was well tolerated, with mild to moderate gastrointestinal adverse effects mostly with early cycles, and modest hematologic toxicity. Unfortunately, relapse appeared to be delayed rather than prevented as there was no plateau of long-term survival. The CC-486 relapse-free survival and OS Kaplan-Meier curves overlapped with placebo after the four-year mark. It has been postulated that the longer duration of exposure to AZA might enhance clinical efficacy by more pronounced effects on DNA hypomethylation; however, this has not been examined in human studies to date.6 Importantly, this trial did not address the question of maintenance therapy after low-intensity regimens such as venetoclax-AZA combinations.

We anticipate that further shifts in the treatment landscape will evolve as less-intensive therapies become standard of care, especially those that straddle both induction and maintenance such as AZA plus venetoclax. Here, the optimal duration of initial therapy remains to be defined, particularly in patients who become MRD negative after treatment. Several other important questions remain. For example, older patients with highly proliferative disease may be offered induction chemotherapy to ensure rapid disease control, and many of these patients will have mutations in FLT3. What is the optimal consolidation and maintenance for these patients beyond induction plus FLT3 inhibitor therapy? Is there a role for combining targeted small molecule inhibitors (e.g., FLT3 inhibitors, IDH inhibitors) with CC-486? Could CC-486 be added to BCL2 inhibitors, as an all-oral “chemotherapy-free” regimen for patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy (NCT04887857)? Can CC-486 combinations further improve the efficacy of CC-486 monotherapy as a maintenance strategy?

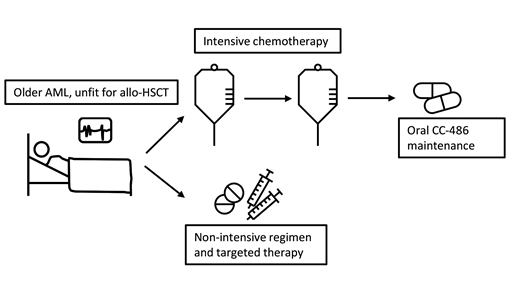

The QUAZAR AML001 study represents an important new option for hematologists, adding oral CC-486 maintenance to the therapeutic algorithm after induction chemotherapy for older patients with AML (Figure). Like many pivotal studies, this breakthrough finding will open the way for testing CC-486 in numerous new contexts including in combination with other targeted therapies up-front or in the maintenance setting for older patients who are ineligible for allo-HSCT.

Clinicians have the option of intensive chemotherapy followed by maintenance CC-486 or novel low-intensity regimens in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are not fit for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).

Clinicians have the option of intensive chemotherapy followed by maintenance CC-486 or novel low-intensity regimens in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are not fit for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).

Competing Interests

Dr. Klose indicated no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Lane receives research funding from BMS (CC-486) and speakers’ honorarium from AbbVie (venetoclax).