The Cases

Case 1

A 30-year-old man with a history of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) was treated with fludarabine, cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, idarubicin, and venotoclax (FLAG-IDA-VEN) and achieved a complete response. He relapsed with acute monocytic leukemia and was treated with high-dose cytarabine in combination with idarubicin, then again with FLAG-IDA-VEN and dexarazone. He presented to the dermatology clinic for a two-day history of nontender purple papules on his chest and abdomen (Figure 1). He noted similar previous papules during chemotherapy that self-resolved. A skin biopsy was consistent with leukemia cutis (LC) from ALL.

Case 2

A 7-year-old boy presented with a persistent blue nodule on the right elbow after a fall five months earlier. Additionally, he experienced right-hand pain, arthralgias, a left supracondylar fracture, pain with ambulation, chills, weight loss, and fatigue. He was evaluated by urgent care, orthopedic surgery, and rheumatology, with workup notable for normal complete blood count, differential, and coagulation; elevated inflammatory markers; and ultrasound showing a hypervascular skin nodule. Treatment included prednisone and hydrocodone, and the patient was referred to dermatology for a possible vascular anomaly. Examination revealed a large tender purple plaque on his right medial elbow and multiple purple-blue macules and nodules on his left upper arm, right preauricular cheek, and right postauricular scalp (Figures 2 and 3). There was preauricular, occipital, and left popliteal lymphadenopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging of the right elbow was consistent with an enlarged lymph node with an overlying abnormal plaque just distal to the node. A skin biopsy and subsequent bone marrow biopsy were consistent with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

The Question

What is the clinical approach, and what cutaneous findings and histopathologic features are associated with these hematologic malignancies?

The Response

Case 1

LC pertains to specific skin manifestations caused by cutaneous seeding of leukemic cells.1,2 LC usually occurs following the diagnosis of the underlying malignancy, though there are reports of it presenting as the primary manifestation. Overall, LC carries a poor prognosis.1-4 Lesions typically resolve only after systemic treatment of leukemia or local irradiation of the involved regions, but there have been reports of spontaneous resolution of LC without treatment.2 LC can occur with all different forms of leukemia but is most commonly seen in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1,2,5 LC in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and ALL is rare, though it may be a presenting symptom or indicative of disease advancement or relapse.1,6,7

The clinical presentation of cutaneous lesions in LC is variable. Common morphologies include firm, red-to-brown papules, plaques, or subcutaneous nodules with a deep purple background. They may be single, grouped, or disseminated, with lesions on the head, trunk, or extremities being most common. LC also has been reported on palmar plantar surfaces, oral mucosa, and genitalia.1,2,8

Histopathology of skin biopsies is integral to making the diagnosis of LC. There is often a nodular or diffuse infiltrate of atypical leukemic cells in the dermis that may extend into the subcutis.1,8 Immunohistochemical stains are essential to characterizing the leukemic infiltrate. In CLL there may be focal epidermal infiltration, and lymphoid cells positive for CD19, CD20, CD43, and CD5 are noted throughout the dermis. A nodular-diffuse and a band-like architectural pattern has also been described.2,8 Histology of myeloid leukemic cells includes larger cells with light cytoplasm and prominent basophilic nuclei.1,8 There is a pleomorphic infiltrate seen in CML composed of myelocytes, metamyelocytes, eosinophilic metamyelocytes, and segmented neutrophilic granulocytes.8 Lysozyme, myeloperoxidase (MPO), CD74, and CD43 may also be positive in myeloid leukemia.8 ALL is characterized by a monomorphic infiltrate of medium to large lymphoid cells with round to indented nuclei, dispersed chromatin, indistinct nucleoli, and very small amounts of cytoplasm. B-lymphoblasts express CD19, PAX5, and CD79a. Most cases show expression of CD10 and the immature marker TdT, as well as variable expression for CD34 and CD20.8 T-lymphoblasts are positive for CD1a, CD3, CD43, CD99, and TdT.8

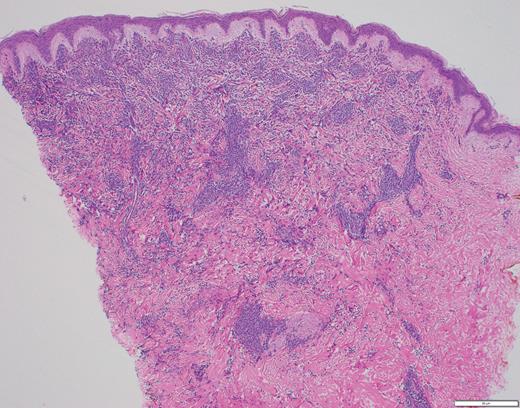

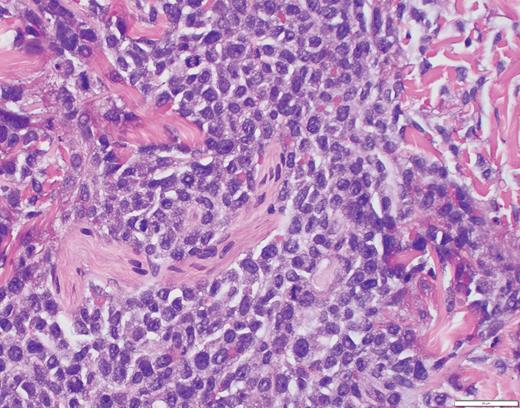

The histopathology in Case 1 demonstrated a diffuse atypical infiltrate composed of mononuclear cells extending from the epidermis to the base of the specimen with an interstitial pattern present between and among collagen bundles along with scattered mitotic figures, supporting the diagnosis of LC related to ALL (Figure 4).

Case 1 histopathology showing mononuclear cells extending from the epidermis to the base of the specimen with an interstitial pattern present between and among collagen bundles along with scattered mitotic figures. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (2×); (B) hematoxylin and eosin stain (40×).

Case 1 histopathology showing mononuclear cells extending from the epidermis to the base of the specimen with an interstitial pattern present between and among collagen bundles along with scattered mitotic figures. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (2×); (B) hematoxylin and eosin stain (40×).

Case 2

BPDCN is a rare, aggressive hematologic myeloid neoplasm derived from the malignant transformation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), which accounts for less than 1 percent of all hematopoietic neoplasms.9-13 While BPDCN may be seen in all ages, patients with BPDCN have a median age of 53 years and a bimodal morbidity pattern of patients younger than 20 years and older than 60 years.13,14 Male patients are more often affected than female patients, and white individuals are more often affected than non-white races, though neither gender nor race are significant predictors of overall survival.10,13,15 Increasing age has been shown to have a higher likelihood of death or relapse, while pediatric cases tend to have a less aggressive clinical course.12,13,15

Skin lesions are often the presenting sign of BPDCN.12,15-17 The cutaneous findings of BPDCN can range in size from a few millimeters up to 10 cm and may appear as brownish to deep purple or as ecchymotic patches, plaques, nodules, or tumors.9,16,17 Patients may present with one or two localized nodules, patches without nodules, or disseminated mixed lesions. Multiple areas of the body may be affected including the head, trunk, and extremities. Mucosal involvement has also been reported.16,17

Patients with disseminated skin involvement at diagnosis are more likely to have detectable systemic disease than patients with more limited skin disease, but the extent of skin disease does not appear to correlate with survival.16 The majority of patients have involvement of the bone marrow, lymph nodes, or visceral organs presenting with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration. The central nervous system is often a site of involvement, though liver, lung, tonsil, soft tissue, and eye involvement have all been reported. There is also a subset of patients who do not display skin findings.9,15-17

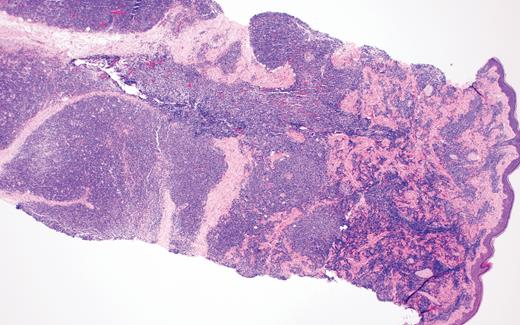

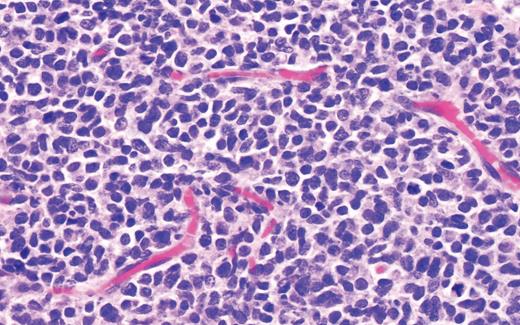

Biopsy of the affected tissue with histopathology and immunohistochemical stains is essential to making the correct diagnosis. The five most common phenotypic markers include CD4, CD56, CD123, CD303, and TCL1, though CD4-negative and CD56-negative cases have been reported.9,16 CD303, TCF4, and TCL1 are specific to pDCs and can help to solidify the diagnosis.15,16,18 BPDCN is negative for other lineage-specific markers such as MPO, T cells (CD3), B cells (CD20 and CD79a), and monocytes (CD11c, CD163, lysozyme).15,16,18 The plaque biopsied in Case 2 demonstrated a dense atypical infiltrate composed of medium-size cells with irregular nuclear contours, fine chromatin, and scant cytoplasm, resembling undifferentiated blast cells with frequent mitoses diffusely involving the dermis (Figure 5). The infiltrate was negative for B-cell and T-cell lineage markers and MPO while positive for CD4, CD123, and TCL1A, supporting a diagnosis of BPDCN.

Case 2 histopathology showing dense atypical infiltrate composed of medium-size cells with irregular nuclear contours, fine chromatin, and scant cytoplasm, resembling undifferentiated blast cells with frequent mitoses and scattered admixed foamy macrophages, some with hemosiderin diffusely involving the dermis. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (2×); (B) hematoxylin and eosin stain (40×).

Case 2 histopathology showing dense atypical infiltrate composed of medium-size cells with irregular nuclear contours, fine chromatin, and scant cytoplasm, resembling undifferentiated blast cells with frequent mitoses and scattered admixed foamy macrophages, some with hemosiderin diffusely involving the dermis. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (2×); (B) hematoxylin and eosin stain (40×).

Conclusion

BPDCN and LC share overlapping clinical morphologies and are difficult to diagnose by clinical presentation alone. Additionally, other dermatologic conditions can present with similar findings including Sweet syndrome, angioinvasive fungal infections, angiosarcoma, erythema nodosum, Kaposi sarcoma, neuroblastoma, cutaneous metastases, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and vascular anomalies.8,17 Subtle clues on full skin examination, particularly the presence of multiple violaceous nodules, can help guide the differential diagnosis. However, LC and BPDCN have variable cutaneous presentations requiring a skin biopsy with immunohistochemistry to make the diagnosis. A tissue culture is also useful to rule out infection. Multidisciplinary care is essential for diagnosis and treatment of both these conditions and should include dermatologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and pathologists. Early cutaneous evaluation and biopsy of an appropriate lesion can help with earlier diagnosis. The high morbidity and mortality of BPDCN and leukemia cutis signify the need for aggressive and rapid treatment.1,8,17

Competing Interests

Dr. Serrano, Dr. Carlberg, Dr. Leventaki, and Dr. Wanat indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.