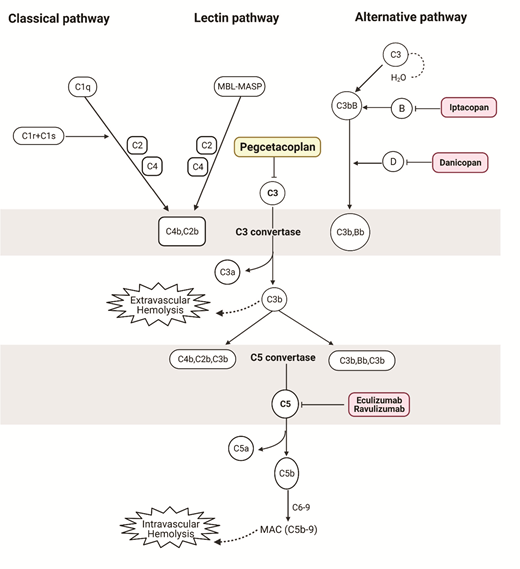

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cells that manifests as hemolytic anemia, bone marrow failure, smooth muscle dystonia, and thrombosis.1 In patients with PNH, a deficiency of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) -anchored complement regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59 due to somatic mutation of the phosphatidylinositol glycan A (PIGA) gene, leads to complement-mediated lysis of PNH erythrocytes.2 Eculizumab and ravulizumab (with its four-fold longer half-life) are humanized monoclonal antibodies against complement C5 that inhibit terminal complement and significantly reduce intravascular hemolysis and thrombosis, the leading cause of death in patients with PNH.3,4 Although patients with PNH on terminal complement inhibitors have a normal life expectancy, up to 20 percent of patients require transfusion support.5 Extravascular hemolysis due to opsonization of PNH erythrocytes with complement C3 accounts for persistent anemia in some patients.6 New complement inhibitors are under investigation to treat PNH including pegcetacoplan, a C3 inhibitor (Figure) administered twice weekly as a subcutaneous infusion.

Examples of complement pathway inhibitors FDA-approved or in phase III clinical trials for the management of PNH. Pegcetacoplan is a complement C3 inhibitor administered twice weekly as a subcutaneous infusion. Extravascular hemolysis due to opsonization of PNH erythrocytes with complement C3 fragments may account for persistent anemia in patients with PNH on terminal complement inhibition (eculizumab or ravulizumab). By inhibiting proximal complement, pegcetacoplan targets both intravascular and extravascular hemolysis.

Examples of complement pathway inhibitors FDA-approved or in phase III clinical trials for the management of PNH. Pegcetacoplan is a complement C3 inhibitor administered twice weekly as a subcutaneous infusion. Extravascular hemolysis due to opsonization of PNH erythrocytes with complement C3 fragments may account for persistent anemia in patients with PNH on terminal complement inhibition (eculizumab or ravulizumab). By inhibiting proximal complement, pegcetacoplan targets both intravascular and extravascular hemolysis.

Dr. Peter Hillmen and colleagues conducted a phase III open-label, controlled trial comparing pegcetacoplan to eculizumab in 80 patients aged 18 years and older with PNH. All patients had hemoglobin of less than 10.5 g/dL despite eculizumab therapy for at least three months. After a four-week run-in phase when all patients received pegcetacoplan 1,080 mg twice per week in addition to eculizumab, patients were randomized to receive pegcetacoplan (41 patients) or eculizumab (39 patients) monotherapy. The primary outcome measured was the mean change in hemoglobin from baseline to week 16 with data censored after the first red cell transfusion. Secondary outcomes include relevant lab markers of hemolysis as well as patient-reported fatigue metrics.

At baseline, the mean hemoglobin across both treatment groups was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.0-10.8 g/dL), and more than 50 percent of patients received four or more transfusions in the previous year. During the 16-week randomization period, patients receiving pegcetacoplan had an average increase in hemoglobin from baseline (+2.27 g/dL vs. -1.47 g/dL in the eculizumab group). A statistically significant reduction in transfusion requirements was observed in the pegcetacoplan group (85% transfusion independence in patients receiving pegcetacoplan vs. 15% in eculizumab). Noninferiority was observed for change in absolute reticulocyte count but not for change in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Fatigue metrics improved in the pegcetacoplan arm.

Common adverse events associated with pegcetacoplan as compared to eculizumab included injection site reactions (37% vs. 3%), diarrhea (22% vs. 3%), and infections (29% vs. 26%). Of note, patients receiving pegcetacoplan may develop meningococcal and other serious infections from encapsulated bacteria; accordingly, appropriate vaccination prior to treatment initiation, or alternatively, continual antibiotic prophylaxis, is recommended. Although breakthrough hemolysis was observed more frequently in patients receiving eculizumab, three patients in the pegcetacoplan group discontinued therapy due to breakthrough hemolysis with significantly elevated LDH greater than three times the upper limit of normal. There were no instances of thromboembolism, meningitis, or death in either treatment group.

In Brief

The results of this trial led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of pegcetacoplan in May 2021. In patients with PNH with persistent, symptomatic anemia due to extravascular hemolysis, pegcetacoplan is a practice-changing advance. We recommend that pegcetacoplan monotherapy be reserved for patients with persistent transfusion dependence (minor or no response to eculizumab)7 or who remain significantly symptomatic despite C5 inhibition, as these patients are likely to benefit the most in terms of increased hemoglobin level and improved fatigue. When considering switching to pegcetacoplan, it is important to establish that anemia is secondary to ongoing hemolysis, rather than marrow failure for which complement inhibition is ineffective.

While pegcetacoplan may offer superior control of hemolysis through proximal complement inhibition, it is unlikely to improve mortality outcomes, as thrombosis is the major cause of mortality in PNH. Furthermore, 80 to 85 percent of patients maintain transfusion independence on C5 inhibition. Route of administration, need for refrigeration, and its short half-life as compared to ravulizumab (every 8-week intravenous dosing) may limit broader adaptation of pegcetacoplan. Continued first-line use of C5 inhibition remains relevant in patients with newly diagnosed PNH requiring treatment and in patients who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic on C5 inhibition.

Further study of pegcetacoplan use in anti-C–5 naïve patients as compared to C5 inhibition and follow-up of patients receiving pegcetacoplan for a longer duration is of great interest. Ongoing monitoring and potential dose adjustments for breakthrough hemolysis are warranted. Results from the trials of other proximal complement inhibitors including the oral complement factor B inhibitor iptacopan as monotherapy, and factor D inhibitor danicopan in conjunction with a C5 inhibitor, are also eagerly awaited.7

Competing Interests

Dr. Gerber and Dr. DeZern indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.