“Cool.”

This was Stan’s quintessential email response when you reached out to him about an interesting patient, a recent publication, or a special event in your life. To be honest, just a single word like that would leave you hanging and wanting more — is that really all you got? Those who trained under Stan could excuse this online brevity because he was an unflinching presence at our conferences and didactics. We always had an opportunity to follow up with meaty conversations about life and hematology across the conference table.

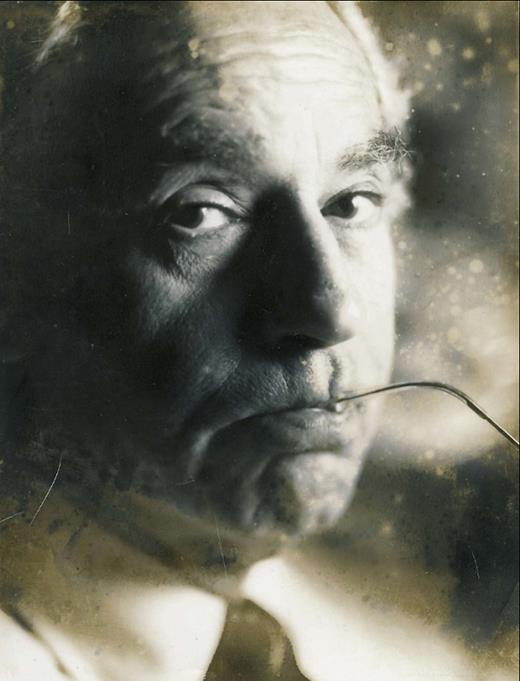

As a founding father of Stanford’s Division of Hematology, Stan was the doting parent of a program he helped nurture for six decades and over which he presided as chief for 27 years. He knew that showing up was at least 50 percent of showing that you care. He effectively used sardonic wit and unfiltered wisecracks to theatrically punctuate substantive teaching points. Stan’s education and mentorship of two generations of hematologists were recognized by the Stanford University School of Medicine’s Albion Walter Hewlett Award, Stanford University’s Walter J. Gores Award, and ASH’s Mentor Award.

Stan recounted that the pediatrician who attended to him for colds in his South Bronx home couldn’t do much, but he was caring, and Stan wanted to be like him. Like Stanford colleague Dr. Irv Weismann and many future physician-scientists, teenager Stan fell in love with the colorful stories of discovery from Leeuwenhoek to Ehrlich, depicted in Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters. His matriculation in the prestigious Bronx High School of Science introduced him to the scientific method and indulged his sense of wonder. After his college years at New York University and the University of Colorado, Stan arrived in Baltimore as part of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s 1950 freshman class and interned on the Osler service. At Hopkins, he developed an affinity for Chief Hematologist, Dr. C. Lockard Conley’s clinicopathologic approach to the evaluation of complex patients. This was foundational to Stan’s development as a notoriously astute diagnostician and clinician.

Amid the Korean War, Stan served his military time as a member of the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service. Stan attended the Stateville Penitentiary in Joliet, Illinois, as a senior assistant surgeon who oversaw University of Chicago–led clinical trials with prisoner volunteers trying to figure out how to fight the scourge of malaria that was debilitating America’s fighting men. He was captivated by Dr. Paul Carson’s and Dr. Ernest Beutler’s seminal work on G6PD deficiency as the basis for primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia and followed their lead in learning experimental techniques to study red cell metabolism. At this time, he was mentored by Dr. Leon Jacobsen and further engaged with Dr. Beutler at the University of Chicago. These were formative interactions that Stan must have thought could provide the prologue of his own origin story, Red Blood Cell Hunters. In 1959, Stan headed west with his wife Peg and was hired as assistant professor in the Division of Hematology at the Stanford University School of Medicine’s newly minted campus in Palo Alto.

Stan started with basic research of the red blood cell (RBC) membrane, studying its structure, function, deformability, and transfer function. However, Stan wanted a clinical outlet; in 1982, he undertook a sabbatical at Hebrew University in Jerusalem to understand the biologic basis of anemia in thalassemia. He led studies that identified the types of excess globin chain accumulation in the membranes of RBCs that led to their premature death, seminal contributions to the understanding of the different pathophysiologies of α- and β-thalassemia.

Stan was heavily involved with ASH. During his tenure as ASH President in 2004, he maintained his long-standing interest in mentoring and education initiatives. He made a large impact on the Society’s global footprint, including establishing the International Consortia on Acute Leukemia (formerly IC-APL) in Mexico and several South American countries. His international ambassadorship extended to the Health Volunteer Overseas (HVO) program, where he helped to innovate hematology care programs in Uganda, Peru, and at the Angkor Hospital for Children in Siem Reap, Cambodia.

Stan was also a winemaker who with his son David, spent 40 years honing Chardonnay, Zinfandel, and other varietals in French oak barrels in his cellar, named Cabrillo Springs. While Stan’s product never touched the hands of a sommelier or graced the pages of Wine Spectator, he developed a vintner’s wisdom that doubled as one his life’s aphorisms: “…the thing you learn when you make wine is patience; nothing happens fast…the mistakes that I’ve made are when I try to hurry things…do not drink the red wine too soon.”

Stan’s tornadic pace in academic hematology did not abate after his “retirement” in 1999. He became the first Hematology Editor for UpToDate, cofounded the Stanford Amyloidosis Center with Dr. Michaela Liedtke, chaired the Stanford Cancer Institute Clinical Trial Office’s Scientific Review Committee, and remained an active principal investigator on a National Institutes of Health grant on anemia in the elderly. Stan maintained his outpatient clinic, research program, and resident didactics at the microscope until a few months before his passing. He never suffered from a withering of youthful enthusiasm; he rode his bike into his 80s, and at age 90, his boyish sense of wonder never lost any of its sheen.

Stan’s affection for hematology was matched only by the love of the outdoors he shared with his family. His annual camping and backpacking trips to Yosemite were a prep for his and Peg’s trek to Everest base camp in 1987. Stan lost Peg to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 2001 and found love again with Barbara Klein. This time, Stan and Barbara introduced the grandkids Andres and Emilia to the national parks, HVO sites and their indigenous peoples, and sanctuaries such as the Galápagos Islands.

While we dearly miss Stan, I’d like to think that if you look hard enough at Albert Bierstadt’s “Sunrise, Yosemite Valley,” you may just be able to see the stealthy cabin that he’s claimed behind some dense pines. Stan soaks in the morning sun, inhales the mist coming off Bridalveil fall, settles into his porch chair, and peers into his microscope. Boy, always wonder.