The Cases

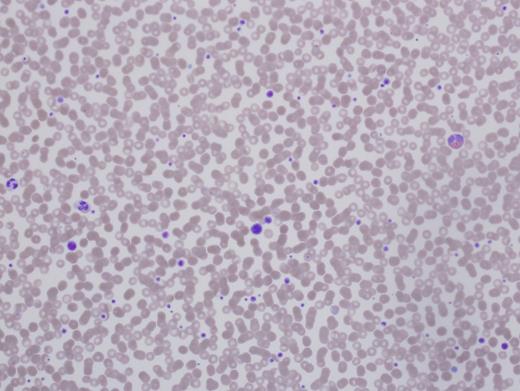

Patient 1 is a 56-year-old woman referred for preoperative evaluation of thrombocytopenia prior to cochlear implants. She was diagnosed with immune thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP) in childhood with platelet counts of 30,000 to 90,000/µL. Therapy included prednisone, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), splenectomy, rituximab, and azathioprine, all with minimal to no effect on her platelet count. She suffered no significant bleeding events through childbirth and surgeries (tonsillectomy, cholecystectomy, C-section, and cataract removal). She has required no red cell transfusions. The patient’s medical history was notable for systemic lupus. There was no family history of blood disorders or abnormal counts. For three weeks prior to this visit she was receiving romiplostim injections. Her platelet count was 143,000/µL. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, white blood cell (WBC) count, and differential were all normal (Figure 1).

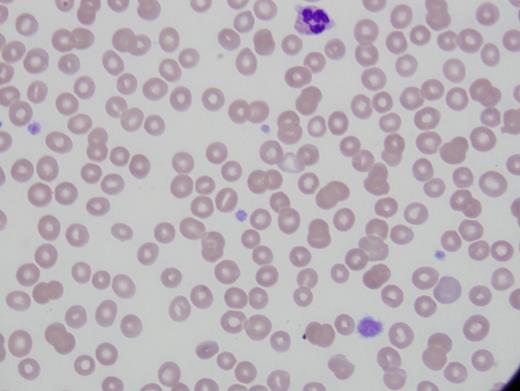

Patient 2 is a 25-year-old woman referred for thrombocytopenia, with counts ranging from 60,000/µL to 100,000/µL. She was diagnosed with systemic lupus and prescribed hydroxychloroquine for joint symptoms. There was no abnormal bleeding with wisdom teeth extraction. Platelet count was 63,000/µL with immature platelet fraction of 37 percent. Immature platelet fraction measures the newest, reticulated platelets and should rise with platelet production. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, WBC count, and differential were normal. Alanine aminotransferase was elevated at 54 U/L and alkaline phosphatase was 148 U/L (Figure 2).

The Question:

What is your approach to distinguishing between inherited thrombocytopenia (IT) and ITP?

My Response:

Diagnosis of ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion. The 2011 ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines1 for the diagnosis of ITP state an International Working Group consensus panel defined primary ITP as a platelet count below 100,000/µL absent other known causes. To what extent must one go to disprove other causes? Testing for hepatitis C and HIV were specifically mentioned as advisable, and a bone marrow examination was unnecessary for “typical” ITP. Typical, however, is not defined. Most hematologists would take a thorough history for drug or toxin exposures, other comorbidities often associated with low platelets such as advanced liver disease, and those in which secondary ITP is found, including lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, and other autoimmune diseases. Abnormalities of other cell lines make an ITP diagnosis suspect, but patients can be anemic from bleeding due to low platelets. Peripheral smear examination often reveals some large platelets, but not giant ones. Treatment with standard high-dose steroids or IVIg usually produces a prompt rise in platelet count, even if not sustained.

Diagnosis of IT requires a high index of suspicion. There are no current guidelines on when to consider IT, but there are some excellent recent reviews (Table).2 Many of the disorders do not have a hemorrhagic presentation. If asymptomatic, the low platelet count may be an incidental finding with blood work done for other reasons. Some are syndromic and comorbidities can provide clues. Most will not respond to immune modulating therapies effective for ITP and are autosomal dominant, but if asymptomatic, other family members are often unaware of their own thrombocytopenia.

Recent Reviews Regarding When to Consider IT

| Gene . | Platelet Size . | Inheritance . | Associated Characteristics . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet-production genes | |||

| CBFA2, RUNX1, AML1 | Normal | AD | Myelodysplasia, AML development |

| GATA-1 | Large | X-linked | Dyserythropoietic anemia; thalassemia-like |

| GFI1B | Large | AD | α granule deficiency |

| ANKRD26 | Normal | AD | Risk of leukemia |

| NBEAL2 | Large | AD/AR | “gray platelet” syndrome; absent α granules, myelofibrosis evolution |

| MYH9 | Large | AD | Nephritis, cataracts, sensorineural hearing loss, elevated LFTs, “Döhle-like” neutrophil inclusions |

| FLNA | Large | X-linked | |

| ACTN1 | Large | AD | Low reticulated platelet counts |

| TUBB1 | Large | AD | |

| CYCS | Normal to small | AD | |

| GP9 | Large | AD | Mono-allelic Bernard-Soulier |

| WAS | Small | X-linked | Wiscott-Aldrich; severe immune deficiency or thrombocytopenia only |

| Gene mutations outside of platelet production | |||

| VWF | Normal to large | AD | von Willebrand disease type 2B |

| ABCG5, ABCG8 | Large | AR | Sitosterolemia, stomatocytosis, xanthomas |

| ADAMTS13 | Normal | AR | Congenital TTP, hemolytic anemia, schistocytes, low ADAMTS13 activity |

| Gene . | Platelet Size . | Inheritance . | Associated Characteristics . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet-production genes | |||

| CBFA2, RUNX1, AML1 | Normal | AD | Myelodysplasia, AML development |

| GATA-1 | Large | X-linked | Dyserythropoietic anemia; thalassemia-like |

| GFI1B | Large | AD | α granule deficiency |

| ANKRD26 | Normal | AD | Risk of leukemia |

| NBEAL2 | Large | AD/AR | “gray platelet” syndrome; absent α granules, myelofibrosis evolution |

| MYH9 | Large | AD | Nephritis, cataracts, sensorineural hearing loss, elevated LFTs, “Döhle-like” neutrophil inclusions |

| FLNA | Large | X-linked | |

| ACTN1 | Large | AD | Low reticulated platelet counts |

| TUBB1 | Large | AD | |

| CYCS | Normal to small | AD | |

| GP9 | Large | AD | Mono-allelic Bernard-Soulier |

| WAS | Small | X-linked | Wiscott-Aldrich; severe immune deficiency or thrombocytopenia only |

| Gene mutations outside of platelet production | |||

| VWF | Normal to large | AD | von Willebrand disease type 2B |

| ABCG5, ABCG8 | Large | AR | Sitosterolemia, stomatocytosis, xanthomas |

| ADAMTS13 | Normal | AR | Congenital TTP, hemolytic anemia, schistocytes, low ADAMTS13 activity |

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; ADAMTS13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AR, autosomal recessive; LFTs, liver function tests; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Developed from Noris P and Pecci A.2

Raised Suspicions

There are no hard and fast rules, and there will be exceptions on both sides of the diagnosis. I think twice about an ITP diagnosis versus IT if I encounter any of the following:

Incidental finding of low platelets with blood testing instead of a bleeding presentation

Very high mean platelet volume or giant platelets (as big as a red cell) on the peripheral smear

Platelet count greater than 30,000/µL at presentation

No or minimal platelet response to steroids, IVIg, or other ITP immune suppression treatments. Note that some IT will respond to thrombopoietin agonists.

“My mom has ITP, too!” or other family members with low platelets.

Family history of myelodysplasia or leukemia; and

Concomitant medical problems present in known IT syndromes

A major barrier to proper diagnosis is insurance companies’ unwillingness to cover genetic testing for diagnostic purposes in adults. The panels are expensive, and the answer is usually “no.” An additional barrier is the need to identify all IT genes. Even in cases with obvious pedigrees of low platelets, often the gene testing is negative for known mutations. Incomplete penetrance, de novo mutations, or autosomal recessive inheritance lower suspicions and thus genetic investigations.2

The importance of the correct diagnosis was laid bare in a report of pregnancy outcomes in 181 women with proven IT. Fifty-seven or 31 percent of cases had been misdiagnosed as ITP, and 44 received unnecessary treatment, including 15 splenectomies.3 In my own practice, I have seen hip replacements owing to avascular necrosis from chronic steroid use given for an incorrect ITP diagnosis.

Patient Follow-up

Patient 1’s case is familiar to most hematologists as the expected clinical findings in MYH9 disorders (formerly called May-Hegglin, Fechtner’s, Epstein, or Sebastian syndromes) with a history of cataracts and sensorineural hearing loss. However, the other manifestations did not develop until later in life, thus the early erroneous diagnosis and treatment. No response to the treatment should have raised red flags about the accuracy of the diagnosis. She did not have renal insufficiency. Her MYH9 gene was sequenced and a novel mutation found. Software predicted this mutation would produce disease. Her platelet count rose with eltrombopag, and her ear surgery was accomplished safely.

The second case observes the daughter of patient 1. Patient 2 has the same MYH9 mutation. Her diagnosis was far more difficult given the lupus and possible liver disease, but her mother was known to have thrombocytopenia, which is key. She was initially misdiagnosed as ITP and encouraged to take steroids, but she wisely refused. Her mother’s MYH9 gene diagnosis came after this patient’s presentation. She does not currently have renal disease or cataracts. Her hearing is slightly decreased.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Neff indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.