The Case

A 46-year-old woman with a long history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma since 2011 presented urgently to a local hospital after being found unresponsive in her bedroom by family. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started immediately, emergency medical services were quickly notified, and she was defibrillated, intubated, and stabilized throughout the next 48 hours. The presenting rhythm identified by EMS was ventricular fibrillation. A cardiac catheterization was done that revealed normal coronary arteries, and the only major finding was that her left ventricular end diastolic pressure was 25 mm Hg (normal, < 12 mm Hg). An echocardiogram (ECG) done the next day indicated overall normal left ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction, 55%). A subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was implanted the next day without difficulty. One week later, she was healing well from any wounds, and the ICD was functioning appropriately.

Her medical history was notable for CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma, with her initial presentation in November 2011 with peripheral lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy; the florescence in situ hybridization was negative. Her treatment included fludarabine and six cycles of rituxan from December 2011 to May 2012, with a complete response. She then had recurrent disease with diffuse lymphadenopathy and bone marrow involvement noted in May 2015. Ibrutinib 420 mg was administered from May 2015 to present, and computed tomography imaging on June 24, 2016, indicated the resolution of lymphadenopathy.

Of note, her other medications included dextroamphetamine-amphetamine, synthroid, and desvenlafaxine ER. Additionally, she reported drinking alcohol heavily for three days prior to her cardiac arrest.

The Question

Does ibrutinib therapy increase the risk of serious rhythm disturbances?

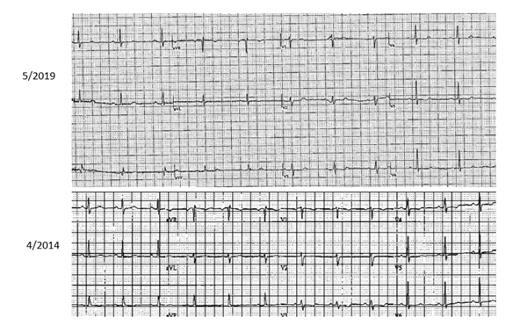

The current electrocardiogram (ECG) on top (May 2019) after ibrutinib is withheld for at least two weeks. The ECG on the bottom (April 2014) precedes the initiation of ibrutinib initially. No significant changes are noted between these two tracings.

The current electrocardiogram (ECG) on top (May 2019) after ibrutinib is withheld for at least two weeks. The ECG on the bottom (April 2014) precedes the initiation of ibrutinib initially. No significant changes are noted between these two tracings.

The Response

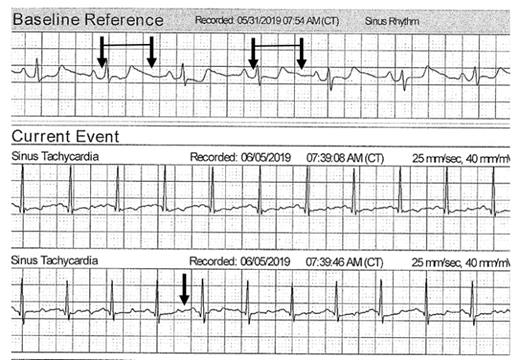

The question of whether ibrutinib is causative of atrial fibrillation has been the subject of much discussion and investigation. Several articles have suggested that it might occur quite frequently in patients with CLL, in one study up to 13 percent,1 and the consequences of atrial fibrillation in patients who were on ibrutinib resulted in a high percentage having to discontinue therapy, most commonly owing to an increase in bleeding events.2 It is very clear that ibrutinib therapy is associated with a higher rate of atrial fibrillation than the “ambient” rate found in patients with CLL who are not on that therapy, and the risk of bleeding is a particularly vexing problem that may lead to discontinuation of this treatment.3,4 What is particularly challenging in this case is whether ibrutinib is associated with a more serious and life threatening rhythm disturbance than just atrial fibrillation. As it turned out, in this patient, there was an episode of sudden death in which she was quickly and effectively resuscitated. This is very good news; however, from a detailed history and extensive evaluation, the cause of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) was not apparent. She had no structural reason for VT (normal left ventricular ejection fraction and normal valvular structures) but was on ibrutinib and dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (a powerful stimulant). She did have significant alcohol exposure, and that certainly may have contributed. Her baseline electrocardiogram in 2014 and the repeat after the event in May 2019 did not reveal any major abnormalities other than nonspecific anterior T wave changes (Figure 1). When a topical wireless monitor was placed, the QT interval appeared prolonged and varied significantly when accessed via the transmission (Figure 2, black arrows). It has been observed that ibrutinib may be associated with VT, but it is not clear that it is a prolonged QT-based mechanism.5-7 Furthermore, this patient had not been on ibrutinib for more than two weeks on the May 2019 ECG or when the wireless monitor was placed.

The top tracing is the topical patch monitor baseline reference several weeks after the sudden death event. The pairs of arrows indicate the QT interval. The bottom tracing shows persistent QT prolongation with a later tracing since the end of the QT segment is more than 50 percent of the R-R interval.

The top tracing is the topical patch monitor baseline reference several weeks after the sudden death event. The pairs of arrows indicate the QT interval. The bottom tracing shows persistent QT prolongation with a later tracing since the end of the QT segment is more than 50 percent of the R-R interval.

Recommendations

It is difficult to associate VT or sudden death with a particular medication. As is frequently the story in cases of sudden cardiac death, there are many possible explanations. In this case, the patient was on ibrutinib, but also dextroamphetamine-amphetamine and had significant alcohol exposure. Exactly what was required to create the milieu for a “perfect storm” and resultant VT is conjecture. After the event, it appeared as though she did have intermittent prolongation of the QT interval that is only detected with prolonged monitoring. Her future therapy for CLL should probably be an alternative agent, mainly because this sudden death event is at least possibly associated with ibrutinib. Nevertheless, it is difficult to identify a safe drug if there are no telltale signs on the baseline standard 12-lead ECG. This case highlights that a topical patch monitoring system for an extended period may identify important findings to establish a connection between a medication and serious rhythm disturbances.8 It is unlikely that such an association could ever be established with an intermittent 12-lead ECG as is the current standard recommendation.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Lenihan indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.