Interest in documentaries has been on the upswing, as anyone who follows podcasts or subscription television can attest. It’s not just technology, the increasing number of media platforms, or the incredibly expanding amount of contemporary footage that has fueled this turnaround. The format of the documentary provides something that neither fiction nor newscasts can accomplish. While broadcast news may be able to deliver the current truth or a vision of it, documentaries provide scope. They look backward across long periods, which allows viewers to see the entire historical picture compressed and illuminated. Unlike fiction, where the bargain with the reader is that something recognizable but unreal will happen, documentaries ask us to acknowledge what is true.

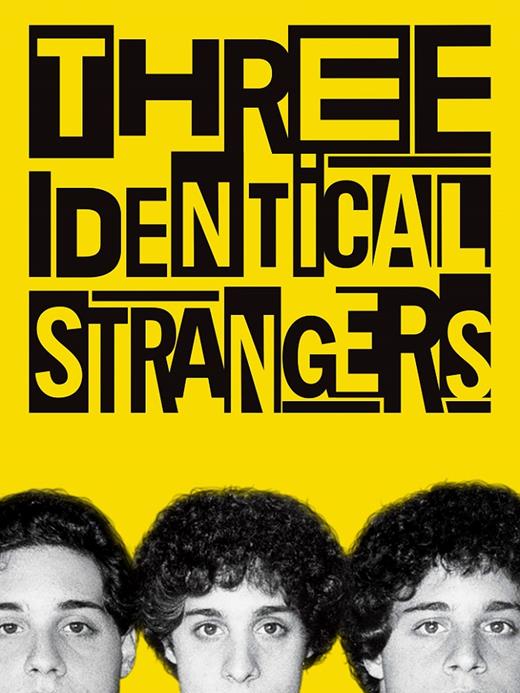

Reclaimed footage, a compelling story, and innovative direction can spotlight stories that might have been otherwise forgotten. At their best, they can also force us viewers to rethink the present. That’s what happened to me on viewing “Three Identical Strangers,” a 2018 documentary film that has remained among the most popular offerings on Netflix since its release.

"Three Identical Strangers," CNN Films and Raw TV, www.threeidenticalstrangers.com, 2018.

"Three Identical Strangers," CNN Films and Raw TV, www.threeidenticalstrangers.com, 2018.

(Spoiler alert: Those who would like to watch the film without spoilers should do so now before reading further.)

The story tells of triplet boys born to a teenage single mother in 1961, relinquished to an adoption agency in New York City, and placed in separate adoptive families. Neither the families nor the boys — Eddy Galland, David Kellman, and Robert “Bobby” Shafran — were told of the other identical siblings’ existence, but a chance encounter by two of the brothers at community college in 1980 is what set events in motion. And what started as a joyful reunion evolved into a painful discovery of the circumstances leading to their separation and the knowledge that they were unwitting participants in a research study designed presumably to examine the effects of nature versus nurture.

The study, a decades long experiment commenced in the 1960s by Dr. Peter Neubauer, a prominent child psychiatrist, involved the film subjects as part of a cohort of multiple births (5 sets of twins and 1 set of triplets; n=13). The 13 families involved in the study all had used the same adoption agency. Dr. Neubauer acquired data on the twin pairs, triplets, and their families in the form of filmed direct observation and interviews of the children, parents, and siblings; psychological tests; and school reports under the pretext of routine evaluation of adopted children. The study ended in 1990, and the design, purpose, and findings of the study have never been published, nor have they been revealed to the 13 families. Its contents were placed under seal at Yale University until 2065 by Dr. Neubauer, who died in 2008.

“Three Identical Strangers” raises many questions, and foremost among them is concern about the medical ethics associated with the Neubauer study. In a Newsweek interview following the film’s release, the director, Tim Wardle, explained that he did not think those involved with the study were immoral. “It’s easy to judge the past by today’s standards,” he stated, “but you have to make some allowances.” Indeed, evidence exists that Neubauer and other prominent contemporary psychiatrists believed twins caused a burden to parents and the family structure, and adoptive twins were better served being raised separately with no knowledge of their sibling(s). Further, the Belmont Report, establishing protections for human subjects, was not published until 1978, long after the study commenced. Nonetheless, an argument may be made that the study fell outside of ethical standards of the time. Wardle acknowledged during a 2019 CNN podcast that Neubauer’s research team approached other adoption agencies to participate in the twin separations, but none were willing to participate in the intentional splitting of multiples for scientific purposes. Moreover, what of the Hippocratic Oath and its obligations?

The issues raised by the film remain timely and challenge us as clinical researchers to ask what our research community is doing today that will not stand up to the ethical test of time. We are reminded of the vital need to be vigilant in our examination of our own actions and those of our collaborators to ensure they are appropriate when designing and conducting research studies, to listen closely to concerns raised by colleagues, to consider the perspectives of patient advocates and other stakeholders, and to periodically take a step back and look at what we’re doing with an eye as critical and focused as that of these filmmakers.

Having been invited to write this essay and discuss how the movie affected my professional worldview, I can report my distressed reaction as a clinical researcher was eclipsed by my visceral response as a parent. Footage of the triplets sharing a crib in their infancy juxtaposed with interviews of them as adults reflecting on the lost opportunity to grow up together made clear the high human cost of the emotional pain inflicted on these children and their adoptive parents. We invite readers who have seen the film and those inclined to view it now to share your thoughts.