I love being a coagulationist. Given our specialty, we are consulted by professionals from every aspect of medical care, from ob-gyn to neurology, nephrology, and sports medicine, and even the quality improvement and legal departments. The work is varied, the clinical questions are fascinating, and I enjoy interacting with and learning from other specialties.

And what unusual consults we get...

In October 2018, I received a phone call from one of the veterinarians at the Duke Lemur Center, explaining that an adult male lemur had a “lame leg” and that a blood clot was suspected, and asking, “How best to treat?” For some background, The Duke Lemur Center houses the world’s largest population of lemurs — small primates native to Madagascar — outside their native habitat. This conservation and research center located in Durham, North Carolina, is an 85-acre sanctuary for these endangered animals.

Never before had I been consulted for a “lame leg,” much less in a lemur. While “lame leg” is not a term we use in human medicine, veterinarians use it to describe an abnormal gait or stance that is the result of a dysfunction in the animal’s locomotor system. In the lemur’s case, the dysfunction was a suspected blood clot.

Charlie is a 12-year-old lemur. In September 2018 he received intravenous sedation through a catheter placed into the lesser saphenous vein (LSV) of his right leg to undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy for evaluation of possible gastritis. It was noted that immediately upon waking up, he did not use his right leg. Diagnosis: “lame leg.” One of the first thoughts of the veterinarian was that the catheter led to a superficial thrombophlebitis of the LSV, and because of associated pain, Charlie was not using his leg. A quick ultrasound of the vein suggested LSV obstruction. Aspirin administered over the next 10 days did not improve the symptoms. This then led to the call from the lemur center given my special interest in thrombosis and anticoagulation, asking if anticoagulants should be used, and what are the next steps?

A 30-minute telephone conversation provided the information to develop a further management plan. Charlie had no leg swelling and no palpable cord. I wondered whether a superficial thrombophlebitis triggered by the LSV catheter during the procedure could have extended into the deep venous system and caused a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), such that Charlie should now be treated with anticoagulants. Our consult service pharmacist immediately, and with excitement, started to look at dosing of direct anticoagulants in light-weight humans (i.e., newborns and children). Charlie weighs 8 lbs (3.6 kg).

However, we wanted a solid diagnosis and not just initiation of empiric anticoagulation. We discussed obtaining a formal venous Doppler ultrasound of the leg by an ultrasonographer to assess whether a DVT was present and whether the veterinarian’s initial suspicion for superficial thrombophlebitis could be confirmed. The study was done, and the results were negative. Charlie did not have a clot.

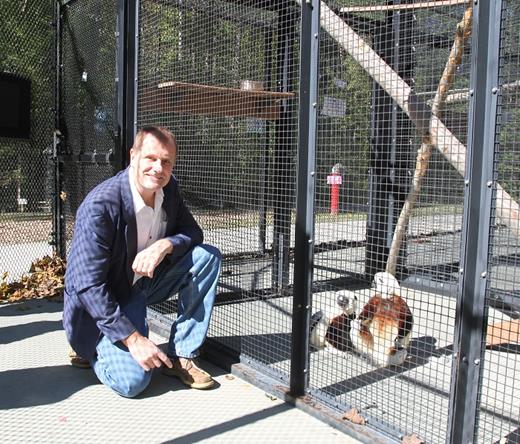

The consult to the coagulationist essentially ended here; however, as a generous thank-you for the phone consultation and help, the veterinarian invited our consult team to a tour of the Duke Lemur Center. What a treat on a beautiful North Carolina autumn day, with colorful leaves on display and a crispness in the air. Unfortunately it was too cold for the lemurs to be out in the trees as they are native to the much warmer Madagascar. We therefore visited the lemurs in their enclosures, Charlie among them. We took our time observing and getting to know him. A sweet fellow, he did not seem to be in pain but avoided putting weight onto his right leg when walking and climbing. Indeed, he had a “lame leg.”

Weeks have gone by; it is February now. I have followed Charlie’s illness with interest, and I admit that I have developed a fondness for him. X-rays have shown some chronic osteoarthritic changes in this foot, and with physical therapy his leg improved. But then, his good (left) leg developed problems; diagnosis: “shifting leg lameness.” He developed intermittent pain or disuse of his arms as well. Blood tests for an inflammatory or systemic infectious cause were negative; an MRI of his spine is pending. I’m going to visit Charlie again come spring. I hope he will have recovered by then.

I love being a coagulationist. And I hope that Charlie will get better.

Further information on the Duke Lemur Center is available atlemur.duke.edulemur.duke.edu. The Center was founded in 1966 and is an internationally acclaimed noninvasive researchnoninvasive research facility housing nearly 240 animals across 17 species — the world’s largest and most diverse population of lemurs outside Madagascar. The Duke Lemur Center is open to the publicopen to the public and educates more than 32,000 visitors annually. Its highly successful conservation breeding program seeks to preserve vanishing species, while its Madagascar Conservation ProgramsMadagascar Conservation Programs study and protect lemurs in their native habitat.