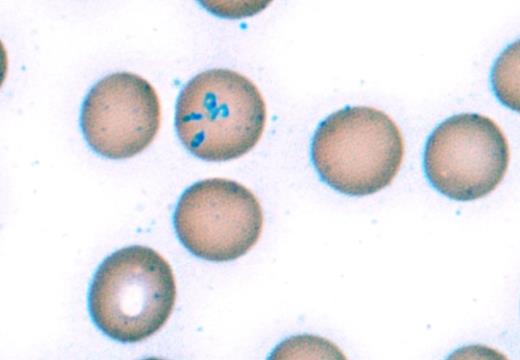

A 65-year-old man with no significant medical history presented with one week of recurrent fevers, chills, and severe headaches. He had recently returned from a summer trip to Maine and New York where he hiked in wooded areas and sustained multiple mosquito and tick bites. A lumbar puncture showed no evidence of meningitis. Laboratory examinations were notable for a Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and mildly elevated transaminases. The peripheral blood smear is shown below.

Image Challenge Nov Dec 2017

A. Lyme disease

B. Babesiosis

C. Ehrlichiosis

D. Anaplasmosis

E. Malaria

Sorry, that was not the preferred response.

Correct!

Babesiosis is a tick-borne infection caused by intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus Babesia. The most common species causing infection, Babesia microti, is endemic to New England and the Great Lakes region and is transmitted by the Ixodes tick, which is also the vector for Lyme disease and anaplasmosis. Most cases occur in the summer months with a peak incidence in July. Symptoms typically begin one to two weeks after a tick bite and include fevers, chills, fatigue, headaches, and myalgias. Common laboratory findings include Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminases. Immunocompromised and asplenic patients are at higher risk for severe infection, which may lead to life-threatening hemolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure, or fulminant hepatic failure.1

The diagnosis is made by observation of the peripheral blood smear, demonstrating intraerythrocytic inclusions including trophozoite ring forms or Maltese cross forms, which are pathognomonic for babesiosis. Serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction testing for babesiosis are also available. Most patients respond to a seven- to 10-day course of antimicrobial therapy, most commonly atovaquone and azithromycin.2 Red blood cell exchange transfusion should be considered for patients with severe disease, including patients with more than 10 percent parasitemia, severe hemolysis, or evidence of renal, hepatic, or pulmonary compromise.3

Lyme disease (option A) is also endemic to New England and is transmitted by the Ixodes tick, but this would not explain the patient’s hemolytic anemia or intraerythrocytic inclusions on the peripheral blood smear. Ehrlichiosis (option C) and anaplasmosis (option D) are also tick-borne infectious diseases that may cause fevers, headaches, cytopenias, and elevated transaminases, but inclusions are present in granulocytes (anaplasmosis) or monocytes (ehrlichiosis), not erythrocytes. Malaria (option E) is also caused by infection with intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus Plasmodium and may have a similar clinical presentation to babesiosis with fevers, headaches, and Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia. However, malaria is not endemic in New England and is not associated with Maltese cross forms, which are pathognomonic for babesiosis.

References

References

Dr. Spinner and Dr. Fernandez-Pol indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.