One of the bigger “unmet needs” in lymphoma is the availability of high-quality treatment options for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The introduction of several novel agents (Table) has brought about progress in the past several years. The response rates are good, but the durability of those responses leaves something to be desired, and it does not take long for patients to exhaust their treatment options.

| Agent . | No. of Patients . | Response Rate (%) . | Median Durability (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | 155 | 33 | ∼ 9 |

| Temsirolimus | 54 | 22 | ∼ 7 |

| Lenalidomide | 134 | 28 | ∼ 16 |

| Lenalidomide-rituximab | 52 | 57 | ∼ 18 |

| Ibrutinib | 111 | 68 | ∼ 18 |

| Acalabrutinib | 124 | 81 | ∼ 18 |

| Zanabrutinib | 86 | 84 | ∼ 18 |

| Venetoclax | 28 | 75 | ∼ 12 |

| Ibrutinib-venetoclax | 24 | 71 (all complete remission) | 12 (80%) |

| Agent . | No. of Patients . | Response Rate (%) . | Median Durability (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | 155 | 33 | ∼ 9 |

| Temsirolimus | 54 | 22 | ∼ 7 |

| Lenalidomide | 134 | 28 | ∼ 16 |

| Lenalidomide-rituximab | 52 | 57 | ∼ 18 |

| Ibrutinib | 111 | 68 | ∼ 18 |

| Acalabrutinib | 124 | 81 | ∼ 18 |

| Zanabrutinib | 86 | 84 | ∼ 18 |

| Venetoclax | 28 | 75 | ∼ 12 |

| Ibrutinib-venetoclax | 24 | 71 (all complete remission) | 12 (80%) |

One can offer allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), which does seem to have curative potential. Approximately 30 percent of patients seem to derive durable disease control from ASCT, but the undertaking comes with 30 percent one-year treatment-related mortality risk, plus the risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Additionally, many patients with MCL are not suitable candidates due to age or comorbidities, or because they lack a suitable donor. For patients who are appropriately fit, it has been my experience that a significant proportion of patients never make it to transplantation because of inadequate disease control.

Given the impressive data with anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy in relapsed or refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, there was reason to test similar strategies in MCL. Well, the results are in from the ZUMA-2 study, and they did not disappoint.1 The CAR-T product is called KTE-X19. It is produced in a manufacturing process that removes circulating CD19-expressing malignant cells under the theory that the removal reduces the possible activation and exhaustion of anti-CD19 CAR-Ts during the ex vivo manufacturing process. To be eligible for this study, patients were required to have been previously treated with anthracycline- or bendamustine-based chemotherapy, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, and a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor. They also needed an absolute lymphocyte count of at least 100 cells per cubic millimeter. The median time from leukapheresis to delivery of KTE-X19 was 16 days. The conditioning regimen was fludarabine at a dose of 30 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide at a dose of 500 mg/m2 on days -5, -4, and -3. KTE-X19 was administered at a dose of 2 × 106 CAR-Ts per kilogram on day 0.

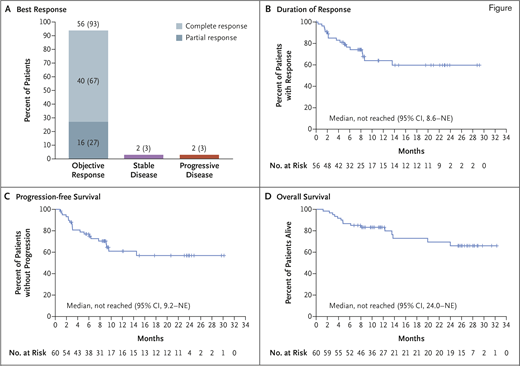

This multicenter trial enrolled 74 patients with a median age of 65 years (range, 38-79 years). For a variety of reasons, six patients did not receive KTE-X19 and were not evaluable for efficacy or toxicity. The risks are not trivial. Cytokine release syndrome can mimic sepsis and was observed in 91 percent of patients, with grade 3 or higher adverse events in 15 percent. Neurologic toxicity is the most troubling aspect of CAR-T therapy because it is poorly understood and there is no proven intervention. In this cohort, 63 percent had neurologic events, with 32 percent experiencing grade 1-2, and 31 percent having grade 3-4 events. Fortunately, no patients died from cytokine release syndrome or neurologic toxicity, and apparently all patients had a full recovery. The overall response rate was 93 percent, and the complete response rate was 67 percent. At 12 months, 61 percent of patients remained progression-free. Several patients had follow-up out to 28 months and remained progression-free (Figure). Are they cured? I wish we knew. Certainly, the plateau in the duration of response curve is a reason for hope. Longer follow-up will clarify the therapeutic ceiling on KTE-X19 in R/R MCL.

Objective response, duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival. A) Numbers and percentages of patients who had an objective response (complete response or partial response) among the 60 patients who had been treated with KTE-X19 and were included in the primary efficacy analysis. B) Kaplan–Meier estimate of the duration of response, as assessed on the basis of review by the independent radiologic review committee, among the 56 patients in the primary efficacy analysis who had a response. Tick marks indicate censored data. Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival and overall survival among the 60 patients who were included in the primary efficacy analysis are shown in parts C and D, respectively. NE, could not be estimated. Reprinted with permission from Wang M et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331-1342.

Objective response, duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival. A) Numbers and percentages of patients who had an objective response (complete response or partial response) among the 60 patients who had been treated with KTE-X19 and were included in the primary efficacy analysis. B) Kaplan–Meier estimate of the duration of response, as assessed on the basis of review by the independent radiologic review committee, among the 56 patients in the primary efficacy analysis who had a response. Tick marks indicate censored data. Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival and overall survival among the 60 patients who were included in the primary efficacy analysis are shown in parts C and D, respectively. NE, could not be estimated. Reprinted with permission from Wang M et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331-1342.

KTE-X19 received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for use in R/R MCL in July 2020. With its availability, how should one manage R/R MCL going forward? Given the high response rates and favorable risk profile, I would suggest that BTK inhibitors remain the therapy of choice. We know that 25 to 35 percent of patients will not respond to BTK inhibition and should be immediately considered for KTE-X19 therapy. What should you do for your BTK inhibitor–responding patient? This is trickier. One approach would be to perform a thorough response assessment at around six months (positron emission tomography imaging and bone marrow evaluation). If the patient is in a complete remission (CR), it would be appropriate to continue BTK inhibition and retain KTE-X19 as an option at the time of relapse. However, if your patient is in partial remission, the data suggest that they are highly unlikely to enjoy a durable remission. In that scenario, I would strongly consider moving on to KTE-X19. Of course, that decision will require a thoughtful conversation with the patient regarding the risks and benefits of remaining on BTK inhibition versus changing therapy to KTE-X19. It will be helpful to have some longer-term follow-up to the KTE-X19 data set, and hopefully we will see that soon. In the meantime, the arrival of this agent was one of the better developments of 2020.

References

Competing Interests

Dr. Kahl indicated no relevant conflicts of interest.