Abstract

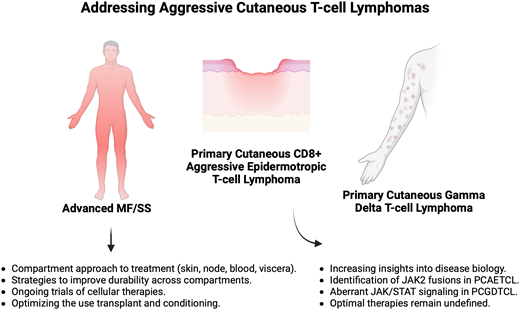

The cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) comprise a diverse set of diseases with equally diverse presentations ranging from asymptomatic solitary lesions to highly aggressive diseases with propensity for visceral spread. The more aggressive CTCLs, which herein we consider as certain cases of advanced-stage mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome (MF/SS), primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma (PCAETCL), and primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTCL), require systemic therapy. Over the last 5 years, treatment options for MF/SS have expanded with biological insights leading to new therapeutic options and increasingly unique management strategies. An enhanced appreciation of the compartmental efficacy of these agents (skin, blood, lymph nodes, visceral organs) is incorporated in current management strategies in MF/SS. In addition, approaches that combine modalities in attempts to increase depth and durability of responses across multiple compartments are being trialed. In contrast to MF/SS, PCAETCL and PCGDTCL remain diseases with few prospective studies to guide treatment. However, recent genomic insights on these diseases, such as the presence of JAK2 fusions in PCAETCL and cell of origin findings in PCGDTCL, have created options for new biomarker-driven strategies.

Learning Objectives

Review emerging agents and strategies for the treatment of advanced-stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

Describe a compartmental approach in managing mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

Discuss recent biological insights in cytotoxic cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and highlight potential therapeutic interventions

Introduction

The cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) comprise a group of non–Hodgkin T-cell lymphomas primarily or exclusively presenting in the skin, though with capability to involve extracutaneous sites.1 The diversity of these diseases, and therefore the limited usefulness of the term CTCL, cannot be overstated. They range from benign lymphoproliferative disorders, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LYP), to aggressive diseases, such as primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma (PCAETCL) and primary cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTCL). Aggressive CTCLs represent an unmet therapeutic need in part due their rarity and biological heterogeneity, both of which have made dedicated trials and uniform strategies challenging to implement and study. Herein we present 3 cases of aggressive-behaving CTCLs, using each case to discuss recent advancements in the understanding and management strategies for these diseases.

CLINICAL CASE 1: ADVANCED Mycosis FUNGOIDES

A 60-year-old female with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) with predominantly patch/plaque disease presented with chest pain. The patient had previously trialed narrowband ultraviolet B light, methotrexate, and bexarotene with persistent disease. Imaging showed a subpectoral nodal conglomerate. Biopsy showed a dense infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes, positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, and T-cell receptor (TCR) alpha, with marked reduction in CD5 and CD7, and negative for TCR delta. Greater than 25% of the infiltrate comprised large lymphoid cells, consistent with histologic transformation. Variable CD30 staining was seen on large cells. Next-generation mutational profiling via a hybridization capture-based platform showed a complex profile, including a TP53 missense mutation.

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

MF/SS: therapeutic framework

MF is the most common CTCL, accounting for nearly 50% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas, whereas Sézary syndrome (SS) accounts for <5% of cases. While the presentation and management of MF/SS is highly variable, most patients have a long natural history requiring multiple treatments with varied responses and durability.2 In the absence of aggressive modalities, namely allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloSCT), conventional treatments are not curative. Patients with early-stage disease generally have an excellent prognosis with survival measured in decades.3 Therefore, an overarching tenant in early- stage disease is not only to maximize disease control but also provide long-term palliation of symptoms and avoid cumulative treatment-related toxicity.

On the other end of the spectrum, more advanced cases, including those with extracutaneous spread, large cell histologic transformation (LCT), folliculotropism, and various genetic events, including mutations in TP53 and CDKN2A/B,4,5 have worse prognosis. Traditional agents for advanced stage disease include single-agent chemotherapy, though multiple new nonchemotherapeutic approaches have been developed over the last decade and represent important advancements. While systemic therapy has traditionally employed a stage-based approach, new understanding that incorporates stage with compartmental burden of disease is preferred, as described recently.6 This framework acknowledges that disease burden often differs between the skin, blood, nodes, and viscera; that even within the skin, the phenotype can vary; and that systemic agents have varied efficacy among these compartments.

MF/SS: newer agents

Newer systemic therapies in MF/SS include brentuximab vedotin (BV), mogamulizumab, and checkpoint inhibitors. Other agents in development include lacutamab, E777, and certain cellular therapies (Tables 1 and 2).

Select advances and upcoming approaches in systemic therapies in MF/SS

| Drug . | Mechanism . | Approvala . | ORRb . | Compartmental effect (ORR)2 . | Notable adverse reaction(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brentuximab vedotin7 | Anti-CD30 ADC | R/R CD30+ MF after 1 prior systemic therapy | 65.6% | ≤IIA: 53% IIB: 68% IIA-IIIB: 75% IVA: 100% (2/2)c IVB: 57% | Peripheral sensory and motor neuropathy |

| Mogamulizumab8 | Anti-CCR4 Ab | R/R MF/SS after 1 prior systemic therapy | MF: 21% SS: 37% | Skin: 42% Node: 17% Blood: 68% Viscera: 0%d | Infusion-related reaction, rash (see text for discussion) |

| E777740 | Recombinant IL2-diptheria toxin protein | R/R MF/SS after 1 prior systemic therapy | 36.2% | — | Infusion-related reaction, capillary leak syndrome, visual impairment |

| Lacutamab14-16 | Anti-KIR3DL2 Ab | No | SS: 37.5%e | Skin: 46.4% Node: 19.6% Blood: 48.2% Viscera: NR | Peripheral edema |

| Pembrolizumab17 | Anti–PD-1 therapy | No (NCCN) | 38% | IB: 0% (0/1) IIB: 100% (2/2) IIIA: 100% (2/2) IIIB: 33% (1/3) IVA: 25% (4/16) | Rash/flare, immune-related toxicity |

| Tislelizumab41 | Anti–PD-1 therapy | No | 46% | — | Rash/flare, immune-related toxicity (observed in only 1 patient with SS in study, recovered within 4 days) |

| DR-01 (NCT05475925) | Anti-CD94 Ab targeting cytotoxic TCLs, including MF, PCAETCL, PCGDTCL | No | Ongoing study, with data to be reported | ||

| Drug . | Mechanism . | Approvala . | ORRb . | Compartmental effect (ORR)2 . | Notable adverse reaction(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brentuximab vedotin7 | Anti-CD30 ADC | R/R CD30+ MF after 1 prior systemic therapy | 65.6% | ≤IIA: 53% IIB: 68% IIA-IIIB: 75% IVA: 100% (2/2)c IVB: 57% | Peripheral sensory and motor neuropathy |

| Mogamulizumab8 | Anti-CCR4 Ab | R/R MF/SS after 1 prior systemic therapy | MF: 21% SS: 37% | Skin: 42% Node: 17% Blood: 68% Viscera: 0%d | Infusion-related reaction, rash (see text for discussion) |

| E777740 | Recombinant IL2-diptheria toxin protein | R/R MF/SS after 1 prior systemic therapy | 36.2% | — | Infusion-related reaction, capillary leak syndrome, visual impairment |

| Lacutamab14-16 | Anti-KIR3DL2 Ab | No | SS: 37.5%e | Skin: 46.4% Node: 19.6% Blood: 48.2% Viscera: NR | Peripheral edema |

| Pembrolizumab17 | Anti–PD-1 therapy | No (NCCN) | 38% | IB: 0% (0/1) IIB: 100% (2/2) IIIA: 100% (2/2) IIIB: 33% (1/3) IVA: 25% (4/16) | Rash/flare, immune-related toxicity |

| Tislelizumab41 | Anti–PD-1 therapy | No | 46% | — | Rash/flare, immune-related toxicity (observed in only 1 patient with SS in study, recovered within 4 days) |

| DR-01 (NCT05475925) | Anti-CD94 Ab targeting cytotoxic TCLs, including MF, PCAETCL, PCGDTCL | No | Ongoing study, with data to be reported | ||

This column refers to approval status with the United Stated Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Response rates in MF/SS are highly nuanced and depend on the response criteria used as well as disease stage, type of lesion (ie, patch, plaque, or tumor), and compartment (ie, skin, blood, lymph nodes, or organ). We encourage direct consultation with the referenced publication to review response rates in detail.

Note that B2 blood involvement was not eligible for the ALCANZA trial.7

Note that only 3 patients with visceral disease received mogamulizumab.7

Results in this row show data from lacutamab use in the SS cohort of the TELLOMAK train. (Not shown are results from the MF cohort.)

Ab, antibody; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; CR, complete response; KIR3DL2, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL2; MF, mycosis fungoides; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NR, not reported; TTNT, time to next treatment.

Select advances in cellular therapies in MF/SS

| Product . | Target . | Product details . | ORR . | Safety . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX13042 | CD70 | Allogeneic, CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited anti-CD70 CAR T cell | ORR: 70% (7/10 at DL ≥3) ▪ PTCL: 80% (4/5 at DL ≥3) ▪ CTCL: 60% (3/5 at DL ≥3) | CRS: 80% ▪ Gr 1-2: 80% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% ICANS: ▪ Gr 1-2: 30% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% |

| CD5.CAR T-cell43 | CD5 | Autologous second- generation CD5.CAR T-cell with CD28 costimulatory domain, non–gene edited | ORR: 44% (4/9 across all DL) ▪ PTCL: 57% (4/7) ▪ CTCL: 0% (0/2) | CRS: 44% ▪ Gr 1-2: 44% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% Neurotoxicity: 1 grade 2 neurotoxicity event that resolved with supportive care Other: severe lymphopenia (<200/µL) in 8/9 patients, median duration 16 days (range 8-27) |

| AFM13 plus NK cells43 | CD30/CD16A bispecific | First-in-class bispecific combined with preactivated, expanded cord blood-derived NK cells | Ongoing phase 2 (NCT05883449, for CHL and CD30+ PTCL) | IRR with AFM13 in ~7% (all ≤ Gr 2), no CRS, ICANS, or GVHD in prior trial (NCT04074746) |

| 5F11-28Z44 | CD30 | Anti-CD30 CAR with CD28 costimulatory domain | ORR: 43% (trial included 20 patients with CHL, 1 patient with ALCL; NCT03049449) | Trial stopped early for toxicity, including prolonged cytopenia with life-threatening sepsis, prolonged severe rashes |

| Product . | Target . | Product details . | ORR . | Safety . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX13042 | CD70 | Allogeneic, CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited anti-CD70 CAR T cell | ORR: 70% (7/10 at DL ≥3) ▪ PTCL: 80% (4/5 at DL ≥3) ▪ CTCL: 60% (3/5 at DL ≥3) | CRS: 80% ▪ Gr 1-2: 80% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% ICANS: ▪ Gr 1-2: 30% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% |

| CD5.CAR T-cell43 | CD5 | Autologous second- generation CD5.CAR T-cell with CD28 costimulatory domain, non–gene edited | ORR: 44% (4/9 across all DL) ▪ PTCL: 57% (4/7) ▪ CTCL: 0% (0/2) | CRS: 44% ▪ Gr 1-2: 44% ▪ Gr ≥3: 0% Neurotoxicity: 1 grade 2 neurotoxicity event that resolved with supportive care Other: severe lymphopenia (<200/µL) in 8/9 patients, median duration 16 days (range 8-27) |

| AFM13 plus NK cells43 | CD30/CD16A bispecific | First-in-class bispecific combined with preactivated, expanded cord blood-derived NK cells | Ongoing phase 2 (NCT05883449, for CHL and CD30+ PTCL) | IRR with AFM13 in ~7% (all ≤ Gr 2), no CRS, ICANS, or GVHD in prior trial (NCT04074746) |

| 5F11-28Z44 | CD30 | Anti-CD30 CAR with CD28 costimulatory domain | ORR: 43% (trial included 20 patients with CHL, 1 patient with ALCL; NCT03049449) | Trial stopped early for toxicity, including prolonged cytopenia with life-threatening sepsis, prolonged severe rashes |

ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CHL, classical Hodgkin lymphoma; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; Gr, grade; GVHD, graft-versus-host-disease; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; IRR, infusion-related reaction; NK, natural killer; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

BV is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in relapsed/refractory (R/R) MF/SS based on the randomized phase 3 ALCANZA trial, which randomized patients to receive BV or choice of methotrexate or bexarotene.7 A greater proportion of patients receiving BV achieved the primary endpoint of objective global response lasting at least 4 months (56% vs 13%, P < .001). In addition, patient-reported reductions in symptom burden, duration of skin response, and progression-free survival were all significantly greater with BV. Importantly, patients with SS were excluded from the ALCANZA trial, and there are limited data in patients with predominantly leukemic disease. In contrast, BV has among the highest response rates in those with tumors, nodal involvement, and LCT (where CD30 expression is often increased),7 and we consider this agent early for such cases.

Mogamulizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), is another approved agent based on the randomized phase 3 MAVORIC trial, comparing mogamulizumab versus vorinostat.8 In this study, mogamulizumab met the primary endpoint of progression-free survival (median 7.7 vs 3.1 months, P<.0001). Mogamulizumab has a notable compartmental effect, with greater efficacy in the blood (objective response rate [ORR]: 68%) and skin (ORR: 42%) than lymph nodes (ORR: 17%). Lasting, deep responses can be seen, especially in those with SS.9 It is increasingly recognized that increases in CCR4 expression often coincide with progression to advanced stage disease and anecdotally, rare patients with gain-of-function mutations in CCR4 may be exceptional responders.10 We find mogamulizumab to be fairly well tolerated and consider it early in those with higher leukemic burden. Important toxicity considerations include mogamulizumab-associated rash (MAR), which can be challenging to distinguish clinically from disease and requires dermatopathology review.11 Underscoring the importance of distinguishing rash from progression, patients who develop MAR have significantly longer survival, potentially due to a robust immune response,12 though they may require treatment interruption and steroids.

MF/SS: emerging agents

Lacutamab is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL2, which is highly expressed especially in SS.13 In an international dose-escalation and expansion trial of 44 patients with R/R MF/SS, lacutamab resulted in an ORR of 36%, with a median duration of response of 13.8 months. Responses were overall higher in those with SS (ORR 43%).14 The TELLOMAK trial, an ongoing, international phase 2 trial (NCT03902184), is further evaluating lacutamab.15,16 Interim evaluation in SS (R/R after ≥2 prior therapies, including mogamulizumab) showed global ORR of 21.6% in 37 patients, with the highest responses seen in the blood (ORR: 38%).15 These results are encouraging in those previously exposed to mogamulizumab.

While not approved, pembrolizumab has activity and has a compendium listing by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. In a phase 2 trial of pembrolizumab in 24 patients with MF/SS, the ORR was 38%.17 Transient worsening can occur and is considered a tumor flare associated with high expression of PD-1. In practice, differentiating a flare from hyperprogression, which has been observed in other T-cell lymphomas, is challenging. Separate reports have shown that PD-L1 structural variants, which can be seen in LCT, may predict sensitivity with deep and durable responses, and more advanced spatial imaging of tumors has identified topographical differences between effector PD1+ CD4+ T-cells and tumor cells that strongly correlate with response.18 Tislelizumab, another anti-PD-1 agent, has efficacy in this space as well, though is not currently available for use in the United States for CTCL (Table 1). Refining who benefits most from checkpoint blockade is an important task in using these agents properly.

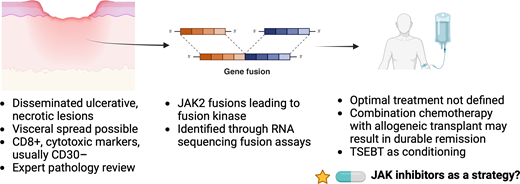

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lyphoma. Patients often present with disseminated eruptive lesions with ulceration. JAK2 fusions leading to kinase activity are considered hallmarks of disease. Created in BioRender. Stuver, R (2024). https://BioRender.com/p16n263.

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lyphoma. Patients often present with disseminated eruptive lesions with ulceration. JAK2 fusions leading to kinase activity are considered hallmarks of disease. Created in BioRender. Stuver, R (2024). https://BioRender.com/p16n263.

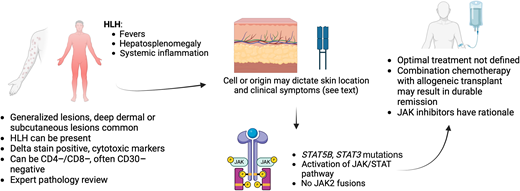

Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma. Patients often present with generalized subcutaneous lesions, often with an inflammatory syndrome. Mutations in the JAK/STAT pathway are common. Created in BioRender. Stuver, R (2024). https://BioRender.com/r56g274.

Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma. Patients often present with generalized subcutaneous lesions, often with an inflammatory syndrome. Mutations in the JAK/STAT pathway are common. Created in BioRender. Stuver, R (2024). https://BioRender.com/r56g274.

MF/SS: strategies to improve depth and durability of responses

Most patients with MF/SS have a chronic course requiring sequential therapies over time, and most therapies provide only partial responses with intermediate durability. Therefore, maximizing depth and durability of responses across disease compartments while maintaining quality of life is key to optimize treatment. One recent approach is the combination of time-limited therapy (radiation) with a maintenance approach (systemic therapy). Historically, total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT) that used a dose of 36 Gy was able to achieve very high responses, including complete responses (CRs). However, even at those doses, responses often were not durable, and TSEBT at those doses could be used only once (rarely twice) per lifetime. There are now multiple datasets using low-dose (LD) TSEBT with similar rates of response (with doses as low as 10-12 Gy, ORR 90% across multiple series19), allowing freedom to use this modality earlier in disease course, as patients can receive repeated courses if desired. Combining LD TSEBT with systemic therapy to prolong durability is being trialed with TSEBT plus mogamulizumab (NCT04128072, NCT04256018), with the rationale to clear leukemic disease seeding the skin.20 Another attempt is LD TSEBT with bexarotene (NCT05296304), again with the idea to reset the skin with a time-limited therapy and prolong response with a tolerable maintenance approach.21

A second strategy to prolong durability is to optimize the tolerability of already effective therapies. An ongoing trial of reduced-dose BV (NCT03587844) is testing this, acknowledging that peripheral neuropathy is a significant limitation to ongoing BV. Doses of 0.9 mg/kg and 1.2 mg/kg are being tested. Interim results of the 0.9 mg/kg cohort22 showed an ORR of 42%, less than that reported in ALCANZA, though with numerically lower rates of peripheral neuropathy and longer response duration. Mogamulizumab represents another agent that could benefit from prolonging durability, as a dose of every 2 weeks is time intensive.

MF/SS: allogeneic transplant

For the aggressive CTCLs, alloSCT remains a critical modality for certain patients. Recent efforts to optimize conditioning have incorporated TSEBT; for example, a regimen originating out of Stanford comprised TSEBT, total lymphoid irradiation, and antithymocyte globulin (TSEBT-TLI-ATG) in a phase 2 trial.23 In this trial, patients who received alloSCT in CR had prolonged survival with low incidence of relapse, especially if they had no evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) in the blood or skin; for MRD-negative patients, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 5 years was 9%. We believe that incorporating radiation is an important strategy when using alloSCT as a highly effective modality to maximize pretransplant disease control. Multiple reports show that alloSCT can result in durable remission in some patients, though selecting which patients are most allosenstive remains challenging. In the aforementioned Stanford trial, patients were selected based on clinically aggressive disease, failure of multiple prior therapies, and predicted survival of less than 5 years without transplant.23 In our practice, we similarly use a case-by-case approach, weighing age and fitness, availability of donors, patient preferences, prior therapies, and alternative options. We note that in the Stanford trial, relapse was more common in the skin (all but 1 relapsed) than at other sites, suggesting (but not proving) that patients with primarily blood-based disease may be more allosensitive than those with greater skin burden. For patients who are deemed not suitable for transplant, our focus is on tolerable and durable treatments that minimize toxicity and maximize disease control and symptom burden over time.

CLINCAL CASE 1: FOLLOW-UP

Given the presence of variable CD30 staining on large tumor cells, BV was initiated at 1.8 mg/kg. A response was achieved lasting seven months followed by progression.

CLINICAL CASE 2: PCAETCL

A 51-year-old male presented with rapidly progressive erosive patches, plaques, and tumors involving the skin of the trunk. Biopsies showed a markedly atypical lymphoid infiltrate with epidermotropism and ulceration, with tumor cells positive for CD3, CD7, CD8, TIA-1, and granzyme B, and negative/ diminished staining for CD2, CD4, CD5, CD30, and TCR delta. Next-generation mutational profiling via a hybridization capture- based platform detected a CAPRIN1- JAK2 translocation. Staging positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans showed multiple avid areas of cutaneous thickening without extracutaneous disease. Treatment was initiated with gemcitabine and liposomal doxorubicin.

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma

PCAECTL classically presents with disseminated eruptive lesions with central ulceration and necrosis.1 While skin lesions predominate, visceral sites can be involved (though nodes seem to be spared).24 The epidermis may appear atrophic with necrosis, ulceration, and invasion of adnexal structures.24 Tumor cells are generally CD3+, CD4−, and CD8+, and also positive for beta F1, granzyme B, perforin, and TIA.24 Most cases lack CD2, CD5, and CD30. Expert pathology review and correlation with clinical presentation (to distinguish between CD8+ MF and LYP type D) are important.

There are no prospective trials dedicated to the management of PCAETCL, and most retrospective series report an aggressive disease course.25,26 In these series, the most reliable long-term survival is observed with induction combination chemotherapy followed by alloSCT in remission.25-29 Multiple induction regimens have been described, mostly borrowed from other aggressive lymphomas, such as EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin).29 Given the known efficacy of gemcitabine and liposomal doxorubicin in CTCL, we have trialed a regimen of gemcitabine plus liposomal doxorubicin in cytotoxic CTCLs, as have others.30 When the goal is to proceed to alloSCT, we trial 1 or 2 cycles followed by response assessment—in patients who achieve CR or near CR, we proceed quickly to alloSCT, usually with an additional cycle to minimize breaks in therapy. Incorporating TSEBT, as described above, in a timely fashion as part of conditioning makes sense in this disease.

Modern genomic approaches have identified recurrent JAK2 fusions in PCAETCL, demonstrating that this event appears to be a hallmark feature of this disease.26,31 In a multicenter study comprising 35 cases of cytotoxic CTCLs (including PCAETCL, PCGDTCL, and other nonclassifiable cytotoxic CTCLs), JAK2 fusions were identified in all 9 cases of PCAETCL.26 These included fusions reported in other known cancers as well as 3 fusions not previously described (PICALM-JAK2, CAPRIN1-JAK2, and SELENOI-ABL1). Functional characterization of these fusions shows constitutive kinase activity that results in cytokine-independent survival ability.26,31 These studies open the door to the use of JAK inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, in PCAETCL. Ruxolitinib has known efficacy in T-cell lymphomas.32 In vitro data show that ruxolitinib can inhibit cell lines harboring JAK2 fusions in a dose-dependent fashion, and we and others are testing ruxolitinib in T-cell lymphomas harboring JAK2 fusions (NCT02974647).

CLINICAL CASE 2: FOLLOW-UP

After 4 cycles of gemcitabine and liposomal doxorubicin, there was extensive healing of all lesions. A PET/CT scan demonstrated CR. The patient proceeded with TSEBT and a matched unrelated alloSCT. At over 100 days from transplant, there was no disease.

CLINICAL CASE 3: PCGDTCL

A 68-year-old female presented with multiple indurated plaques and bruised subcutaneous nodules over the extremities. On presentation, the patient appeared ill. The initial laboratory results showed pancytopenia with elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, and soluble IL2 receptors. A deep punch biopsy showed a panniculitic lymphoma with variably sized tumor cells with rimming of adipocytes. Cells were positive for CD2, CD3, TIA-1, granzyme B, CD56, and negative for CD4, CD5, CD7, and CD8. TCR delta was diffusely positive. Histiocytes were seen with ingested cells within their cytoplasm. A PET/CT scan showed widespread cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions.

Primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma

PCGDTCL usually presents with generalized patches, plaques, and deep dermal or subcutaneous tumors.1 Patients are often acutely ill. The characteristic tumor cell phenotype is positive for TCR gamma delta (but beta F1-negative) and multiple cytotoxic proteins.33,34 T cells generally lack CD4 and CD8, with variable expression of CD5 and CD7. Clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma and delta genes is observed. Clinicopathologic correlation is key for diagnosis, and consideration should be given to gamma delta variants of more indolent cutaneous disorders, such as LYP, or rare cases of otherwise classic MF in which gamma delta expression can be observed. Historically, PCGDTCL was thought to predominantly express V delta 2, though recent studies show that V delta 2 lymphomas primarily arise in fat or subcutaneous tissue, whereas epidermal or dermal gamma delta lymphomas are of V delta 1 origin.35 These cell of origin discoveries seem to correlate with clinical behavior in finding that V delta 2 cases (fat) appear to have worse outcomes, with potential resistance to therapies and high association with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.35

Given the aggressive nature of PCGDTCL, our approach has generally mirrored strategies used for other cytotoxic gamma- delta T-cell lymphomas, namely hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, in which we use ifosphamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) followed by alloHCT in CR or near CR. Like PCAETCL, multiple regimens have been described, though a consistent factor in long-term survival is receipt of alloSCT.34,36-39 Unlike in PCAETCL, JAK fusions have not been observed, though activating mutations in STAT5B and STAT3 are frequent in PCGDTL.26,35,40 These findings again have therapeutic implications, suggesting that inhibition of this pathway may be a promising strategy to trial. In the aforementioned phase 2 trial of ruxolitinib in T-cell lymphomas,32 responses were observed in cutaneous gamma delta lymphomas, though all eventually progressed, suggesting that response to small molecule inhibition may be variable. CD94 is a potential therapeutic target expressed on cytotoxic T-cells, and several strategies are under evaluation in CD8+, gamma delta, and other T-cell lymphomas originating from cytotoxic T-cells based on this target (for example, see NCT05475925).

CLINICAL CASE 3: FOLLOW-UP

Chemotherapy with ICE was administered alongside dexamethasone for the treatment of PCGDTCL and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Aggressive stabilization was necessary, and after 1 cycle of therapy, a repeat PET/CT scan showed dramatic decreases and resolution in multiple lesions. The patient was evaluated for alloSCT and began physical rehabilitation due to deconditioning, which is ongoing with concomitant treatment.

Conclusion

Patients with advanced-stage cutaneous lymphomas often suffer a chronic course with multiple relapses requiring sequential systemic therapies. Thankfully, the last decade has witnessed much progress, though the durability of most agents remains relatively short. Herein we described multiple efforts using a compartmental approach that takes into account stage, site of disease, and ability to combine treatments across compartments (TSEBT and systemic therapy) to achieve greater depth and durability of response. For rarer cytotoxic lymphomas, recent insights into biological origins of PCGDTCL and PCAETCL are a step forward into more rational management.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Robert Stuver has research funding from Pfizer (all paid to the institution).

Steven M. Horwitz has served as a consultant for Affimed, Abcuro, Corvus, Daiichi Sankyo, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, ONO Pharmaceuticals, Seagen, SecuraBio, Takeda, and Yingli. Steven M. Horwitz has research funding from ADC Therapeutics, Affimed, C4, Celgene, Crispr Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Dren Bio, Kyowa Kirin, Millennium /Takeda, Seagen, and SecuraBio (all paid to the institution).

Off-label drug use

Robert Stuver: The manuscript describes off label use of pembrolizumab. Investigational approaches are described. All efforts have been made to note when an investigational drug is being described by provider the most up to date reference of the relevant clinical trial or the NCT number.

Steven M. Horwitz: The manuscript describes off label use of pembrolizumab. Investigational approaches are described. All efforts have been made to note when an investigational drug is being described by provider the most up to date reference of the relevant clinical trial or the NCT number.