Abstract

Leukemia and lymphoma are 2 common hematologic cancers in adolescents and young adults (AYAs, age 15-39 years at diagnosis); however, this population has historically had lower clinical trial enrollment and less dramatic improvements in overall survival compared to other age populations. Several unique challenges to delivering care to this population have affected drug development, clinical trial availability, accessibility, and acceptance, all of which impact clinical trial enrollment. Recently, several national and institutional collaborative approaches have been utilized to improve trial availability and accessibility for AYAs with hematologic malignancies. In this review, we discuss the known barriers to cancer clinical trial enrollment and potential approaches and solutions to improve enrollment for AYAs with leukemia and lymphoma on clinical trials.

Learning Objectives

Identify the barriers to clinical trial enrollment for AYA leukemia and lymphoma patients at the national, institutional, and provider levels

Evaluate and apply collaborative approaches to facilitate clinical trial enrollment for AYAs with leukemia and lymphoma

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 24-year-old presents to a large academic medical center with a history of back pain, fever, and progressive dyspnea. A chest CT reveals a large anterior mediastinal mass with compression of the superior vena cava. A biopsy confirms primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL). Due to respiratory distress, the patient is admitted to medical oncology and started on R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). The patient is presented at a joint pediatric-adult hematologic malignancy tumor board. The pediatric oncologist and AYA champion for the children's hospital recommend enrollment in a Children's Oncology Group (COG) protocol, ANHL1931 (Nivolumab in Combination with Chemo-Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma). This study is open at their site, and the adult hematologist/oncologist can enroll as they share an institutional review board (IRB). The adult oncologist states that, unfortunately, therapy had been started. The AYA champion notes that patient can still be enrolled as the first cycle is “doctor's” choice to allow patients to receive emergent treatment prior to enrollment.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 19-year-old obese woman is evaluated in the emergency room for increased bruising and fatigue and diagnosed with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). Aware that AYA patients have better survival on pediatric protocols, the adult oncologist wants to ensure that there are no active pediatric leukemia trials that this patient would be eligible for. Neither research office has any upfront treatment trials available. However, the cross-network supportive care trial ACCL1931 (A Randomized Trial of Levocarnitine Prophylaxis to Prevent Asparaginase-Associated Hepatotoxicity in AYAs Receiving Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Therapy) is only open in the pediatric research office due to staffing issues in the adult research office. Given the patient's age and weight, both providers agree that offering the trial would be in the patient's best interest.

Introduction

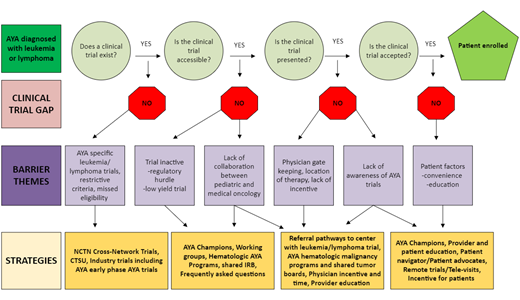

AYAs with leukemia and lymphoma face significant challenges in participating in cancer clinical trials (CCTs), and limited enrollment slows progress in identifying optimal approaches to improve survival and quality of life.1 Disparities in care and outcomes persist across the cancer journey, from diagnosis to long-term follow-up, underscoring the need for tailored CCT opportunities. CCT enrollment is impacted by numerous factors, including trial availability and local accessibility at institutions as well as patient acceptance of CCTs. AYAs may be treated in either a pediatric or adult-based center, and differences in the treatment approaches can impact outcomes. Collaborative efforts within the research community for hematologic malignancies are now focusing on inclusive trial designs involving pediatric and adult groups to address these challenges. This review focuses on barriers and facilitators to AYA leukemia and lymphoma trial enrollment and recent collaborative efforts and initiatives to improve enrollment (Figure 1).

Trial availability

A key driver of AYA CCT enrollment is availability of an appropriate CCT that has been developed and exists for a patient with leukemia and lymphoma. Barriers to the development of leukemia and lymphoma CCTs for AYA patients include trials with incompatible eligibility criteria, differences between pediatric and medical oncology treatment approaches, differences in drug toxicities based on age impacting CCT design and inclusion of AYAs, and regulatory requirements.

Eligibility requirements

Historically, risk stratification for hematologic malignancies has differed between medical and pediatric oncology protocols. To address eligibility issues, there have been efforts to harmonize staging criteria and risk stratifications between pediatric and medical oncology groups and among collaborative groups. In 2011, a workshop was held to modernize recommendations for evaluation, staging, and response assessment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and the Lugano classification was proposed to improve evaluation of patients with lymphoma and enhance the ability to compare outcomes of CCTs.2 In 2013, the Staging Evaluation and Response Criteria Harmonization (SEARCH) for Childhood, AYA Hodgkin Lymphoma (CAYAHL) group was created to standardize the staging of HL between pediatric cooperative groups.3

Treatment approach

Differences in chemotherapy backbones between adult and pediatric cooperative groups remain a challenge when developing new CCTs. When developing the first large cross-network prospective phase 2 trial for advance HL, the S1826 study committee decided to use the standard adult AVD (doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) backbone over the pediatric ABVE-PC (a modified ABVD chemotherapy regimen of doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine, plus etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide) backbone based on pooled analysis of adolescent patients from COG legacy trials.4 Early results of S1826 show that the addition of nivolumab to AVD improved progression-free survival compared with the addition of brentuximab vedotin and was less toxic.5 This study, which was open at academic and community oncology practices, was the largest US cross-network effort in HL ever conducted. The study provided greater access to novel agents across the age spectrum and is a model for how cooperative groups can work together from trial conception to better serve AYAs. SWOG was the trial sponsor for S1826 in collaboration with the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) cooperative groups. In ongoing collaboration, NCT05675410 (Randomized Phase 3 Interim Response Adapted Trial Comparing Standard Therapy with Immuno-Oncology Therapy for Children and Adults With Newly Diagnosed Stage I and II Classic HL) is now open for enrollment for HL patients 5-60 years old. Despite barriers to standardizing treatment approaches across pediatric and medical oncology for AYAs with hematologic malignancies, there have been notable exceptions of trials that have successfully overcome these challenges. The prospective CALGB (Cancer and Leukemia Group B) 10403 trial treated AYA ALL patients with a pediatric treatment regimen and demonstrated improved overall survival with manageable toxicities.6 Studies that evaluate novel agents while permitting flexibility in the choice of chemotherapy backbone facilitate accrual in both pediatric and adult-based centers. For example, the current PMBCL trial (ANHL1931) demonstrated rapid, sustained enrollment of AYA participants with a rare disease.

Toxicity profiles

Differences in drug pharmacokinetics and toxicities between pediatric and older adult patients and between younger and older AYAs can impact study design and drug dosing. A prime example is the use of PEG-asparaginase in ALL treatment protocols. For pediatric patients, the use of asparaginase containing chemotherapy backbones has been critical to the improvement in overall survival, and patients who are unable to receive most prescribed doses experience a higher relapse rate.7 Obese AYA patients (like the patient in case 2) are at increased risk for PEG-asparaginase–induced hepatotoxicity and inferior outcomes due to treatment delays or holds.8 This finding influenced the design of subsequent pediatric and adult trials with dose capping rules for the current COG B-ALL study (AALL1732) and the Alliance-sponsored trial A041501 for AYA patients with B-ALL. Supportive care measures, such as levocarnitine prophylaxis to prevent hepatotoxicity, are being examined as part of COG ACCL1931.

Regulatory requirements

Participants younger than 18 years often have regulatory requirements that differ from those for adult participants. Adult safety data are required prior to the use of investigational drugs in patients under 18 years old, so younger AYAs are often excluded from upfront trials.9 At the individual patient level, this reduces the availability of potential life-saving interventions to adolescents. At a population level, this results in a sparsity of data regarding AYA patients' response and tolerance to novel therapies. The Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity for Children Act (RACE Act, 2017) requires pharmaceutical company sponsors seeking approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for drugs with a molecular target that is relevant to pediatrics to include plans for investigation in a pediatric population, including safety, dosing, and efficacy data. According to the US Government Accountability Office, since its implementation in 2020, the RACE Act has led to the development of 32 pediatric studies for drugs initially developed for adult cancer patients.10

There are several ALL trials in development by SWOG and COG for KMT2A-rearranged ALL that will include all ages; there is also a SWOG-sponsored phase 1 trial for relapsed/refractory T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (NCT04315324) with a planned amendment to lower the age of eligibility to 12 years, expanding access to a novel drug for T-ALL.

Trial accessibility barriers

Physician-specific barriers

Physician gatekeeping is a significant barrier to trial enrollment. AYAs typically learn about trials through their physicians, and they are more likely to enroll when their physician endorses the trial as the best treatment option.13 Differences in treatment paradigms between pediatric and adult hematologist/oncologists who treat AYAs can limit trial offerings. AYAs treated by pediatric oncologists are more likely to enroll in trials compared to those treated by adult hematologist/oncologists.14-18 Despite an increase in available cross-network trials, confusion can remain among research teams regarding who can be enrolled and who is responsible for trial adherence, reporting, and audits.

Strategies to enhance physician endorsement include increasing awareness of AYA trial availability among providers who treat AYAs, improving understanding of cross-network enrollment, and addressing barriers to effective physician-patient communication. In 2018, the COG AYA Committee established the AYA Responsible Investigator (RI) Network.19 This diverse network of >140 members includes physicians, nurse practitioners, nurse navigators, and research staff working to optimize AYA enrollment in NCTN cross-network trials through education and peer support. Initiatives include monthly webinars to educate on cross-network enrollment processes, peer support by reviewing local barriers, and sharing successful initiatives to improve enrollment.20 Results from an RI Network–wide survey on barriers and facilitators to AYA enrollment informed the planning of interventions such as how to implement a CCT screening process for AYAs.21 The group created a Frequently Asked Questions document to clarify accessibility and NCTN cross-enrollment (Supplementary Figure 1). For example, a patient who is over 12 years may be eligible for both COG and SWOG trials, but if treated at a pediatric center, the team may not be aware that the child could be treated on a SWOG protocol. Cross-training research staff and having AYA-specific research coordinators may facilitate the enrollment process for NCTN cross-network trials.21,22

Lack of communication and collaboration between pediatric and adult oncology teams further hinders AYA enrollment. Even with increased availability of leukemia and lymphoma cross-network trials (Table 1), in many centers, there are few, if any, opportunities for pediatric and adult clinical teams to interact and discuss new cases. Evidence suggests that AYA-specific clinics, tumor boards, and programs that include both pediatric and adult hematologist/oncologists improve collaboration and awareness of AYA CCTs.20,23 Institutional approaches, including the presence of AYA working groups and coordinators, enhance enrollment.24 Implementation of joint screening with representation from pediatric and adult-based teams is 1 strategy for optimizing enrollment on AYA CCTs.25,26

National Clinical Trials Network and National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program lymphoma and leukemia trials open at time of submission

| Protocol number . | Phase . | Diagnosis . | Age . | Drugs . | Group . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | |||||

| A041501 | 3 | Newly diagnosed CD22+, Ph negative precursor B-ALL | 18-39 years | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | ALLIANCE COG ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG CCTG |

| AALL1821 | 2 | First relapse B-ALL | 1 to 30 years | Blinatumomab and nivolumab | COG ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG ALLIANCE |

| Lymphoma | |||||

| A051901 | 1 | Primary CNS lymphoma | 18 years and older | Lenalidomide and nivolumab | ALLIANCE |

| A051902 | 2 | CD30 negative peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 18 years and older | Duvelisib and CC-486 (azacitidine) | ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| ANHL1931 | 3 | Newly diagnosed primary mediastinal B-cell | 2 years and older | Nivolumab | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| AHOD2131 | 3 | Newly diagnosed stage I and II classical Hodgkin lymphoma | 5 to 60 years | Brentuximab vedotin and nivolumab | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| E4412 | 1/2 | Relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma | 18 years and older | Ipilimumab, nivolumab, and brentuximab vedotin | ECOG-ACRIN COG ALLIANCE NGR SWOG |

| Multiple diagnoses | |||||

| ACCL1931 | 3 | Newly diagnosed B-ALL, T-ALL, LLy, MPAL | 15 to 39 years | Levocarnitine | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN SWOG |

| ACCL21C2 | Other | Any cancer diagnosis | 6 months to 36 years | COVID-19 vaccine | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| Protocol number . | Phase . | Diagnosis . | Age . | Drugs . | Group . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | |||||

| A041501 | 3 | Newly diagnosed CD22+, Ph negative precursor B-ALL | 18-39 years | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | ALLIANCE COG ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG CCTG |

| AALL1821 | 2 | First relapse B-ALL | 1 to 30 years | Blinatumomab and nivolumab | COG ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG ALLIANCE |

| Lymphoma | |||||

| A051901 | 1 | Primary CNS lymphoma | 18 years and older | Lenalidomide and nivolumab | ALLIANCE |

| A051902 | 2 | CD30 negative peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 18 years and older | Duvelisib and CC-486 (azacitidine) | ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| ANHL1931 | 3 | Newly diagnosed primary mediastinal B-cell | 2 years and older | Nivolumab | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| AHOD2131 | 3 | Newly diagnosed stage I and II classical Hodgkin lymphoma | 5 to 60 years | Brentuximab vedotin and nivolumab | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

| E4412 | 1/2 | Relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma | 18 years and older | Ipilimumab, nivolumab, and brentuximab vedotin | ECOG-ACRIN COG ALLIANCE NGR SWOG |

| Multiple diagnoses | |||||

| ACCL1931 | 3 | Newly diagnosed B-ALL, T-ALL, LLy, MPAL | 15 to 39 years | Levocarnitine | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN SWOG |

| ACCL21C2 | Other | Any cancer diagnosis | 6 months to 36 years | COVID-19 vaccine | COG ALLIANCE ECOG-ACRIN NGR SWOG |

Lead group is in bold.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CCTG, Canadian Cancer Trials Group; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG-ACRIN, ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (merger of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN)); LLy, lymphoblastic lymphoma; MPAL, mix phenotype acute leukemia; NGR, NRG Oncology (merger of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), and Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)).

To address the communication barrier between providers, in 2020 the RI Network established the AYA Trial Access Quality Initiative (ATAQI) to systematically study interventions to improve AYA enrollment through quality improvement methodology.27 A year-long pilot of 9 institutional teams of pediatric and medical dyads chose a disease group of focus (eg, hematologic malignancies or sarcomas) and 1 of 3 interventions: (1) creation of a shared dashboard of AYA-relevant trials, (2) creation of a joint tumor board, or (3) weekly communication between adult and pediatric providers to discuss patients and available CCTs. The learning collaborative had monthly calls and 3 learning sessions. Process and outcome data are currently being evaluated.

Institutional barriers

Reluctance to activate trials at institutions is a well-known barrier to trial accessibility.1 Despite many AYA trials being available nationally, local sites often do not open these trials and struggle to enroll eligible AYAs. Previously, only COG members could enroll in COG-led trials, but current NCTN procedures allow broader enrollment.28

Since the COVID pandemic, physicians are under increased pressure from their institutions to open fewer trials due to limited resources, especially in rare cancers with low accrual. Incentivizing sites for prioritizing AYA enrollment, with additional funding, reimbursements, or National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program credits, could improve enrollment.24 The location of the trial site significantly impacts AYA enrollment. AYAs are less likely to enroll in CCTs if they must travel long distances for extra appointments.29 While children are more likely to receive care at academic institutions, many AYA patients receive care at local community cancer centers without access to CCTs due to limited anticipated enrollment.18,30,31

A study comparing AYA CCTs at a children's hospital and its affiliated adult hospital found that only 4.1% of AYAs treated at the adult institution enrolled in a CCT, compared to 26.4% at the children's hospital. The children's hospital also had higher trial activation, and, when AYAs and children were both treated at a children's hospital, CCT accessibility was similar.15 Thus, within institutions, enrollment in CCTs may depend on the treating service.32

Regulatory barriers

Research team members identified regulatory burdens as a significant barrier to enrollment, especially in smaller research offices.18 Regulatory offices may be unfamiliar with cross-enrollment procedures, and limited staff and resources further impact the number of locally activated trials. The absence of shared IRB approvals poses a considerable barrier. Clinics treating both pediatric and adult patients may require increased resources to support AYA trials.

Smaller centers tend to open fewer CCTs due to site selection by sponsors; logistical support needs, such as personnel needed and cost of opening; necessary therapeutic or diagnostic technologies; and scientific or ethical scrutiny by local research committees and IRBs. Even though patients could access more trials at larger centers, referrals from smaller centers are limited by a lack of infrastructure.33 Improving the assessment of trial workload before opening trials and implementing CCT navigators (CTNs) could help manage institutional resources more effectively.24

Patient-specific barriers

AYAs often have time constraints due to jobs, education, and family responsibilities, making it difficult to commit to the additional appointments and tests required for CCT participation and adherence to protocols. Financial concerns, such as inadequate health insurance and fears about employment, hinder AYA enrollment.13,18 Strategies that have improved patient adherence in CCTs include support from AYA-designated coordinators and CTNs.34,35 CTNs specifically trained in enrollment, disease-specific treatment approaches, and patient education may be based in pharmaceutical companies, cancer centers, or national organizations such as the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. The American Cancer Society's free CCT service served 6903 patients over 3 years. Among the 1987 patients with follow-up information on enrollment, 11.0% enrolled in a CCT.36 CTNs play a critical role in investigating which trials are open and enrolling.37 Including funding in the budget for patient assistance, community engagement efforts, and participant compensation are additional strategies.

It is crucial to seek feedback from patients to identify which interventions and protocols are practical and to balance scientific research questions with maintaining realistic expectations of patient participation. Patient advocacy groups can be involved to assist with recruiting participants and getting feedback on trial design and to create patient-friendly graphics and social media content that effectively translates the study's design and results in an engaging manner. Several national organizations have established formal programs to educate patients and advocates. For 20 years, the American Association for Cancer Research has connected advocates and scientists during scientific meetings through the Scientist ↔ Survivor Program.38,39 Taking the trial to the patient works well for AYAs. The Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Teletrials Program has developed standard operating procedures to enable teletrials and improve AYA CCT opportunities.35 This model provides access to pediatric trials in adult centers and vice versa via telemedicine, allowing patients to remain in age-appropriate care.

Many programs lack dedicated CTN or AYA navigators and the infrastructure to build strong AYA initiatives. To address this, institutions might consider identifying AYA champions, involving a diverse range of staff beyond oncology, sharing resources across institutions and departments, and forming strong community partnerships, thereby strengthening referral networks.

Conclusions and future state

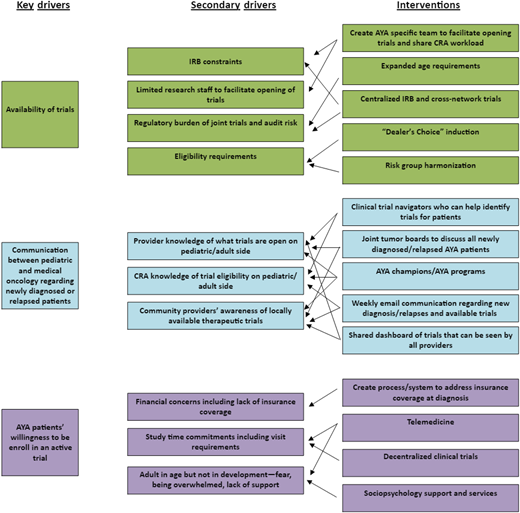

Several levels of barriers exist to AYA participation on leukemia and lymphoma CCTs; however, there have been significant strides in the last decade at all levels. Gaps still exist, and there are many opportunities to improve enrollment further. Some strategies and examples are highlighted in Table 2. Addressing the identified issues necessitates communication and collaboration among all stakeholders, including regulatory agencies, sponsors, academic institutions, IRBs, community providers, patients, and patient advocates. Innovative solutions with multistakeholder involvement need to be explored to support standards of care for treatment and monitoring of disease, supportive care, and follow-up.

Barriers and strategies for clinical trial accrual for AYA patients with examples of interventions

| Barrier themes . | Strategies that can address barriers . | Examples of intervention . | Exemplar papers/trials (PubMed) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication amongst members of team | Forums to discuss cases Institutional policies Identifying unique AYA care Working groups | Tumor boards AYA champions AYA programs AYA working groups | PMID:3222270940 PMID: 3526464220 PMID: 3207778219 |

| Regulatory barriers | Share resources Assess workload/budget and staffing Stakeholder engagement | Shared IRB/central IRB Novel trial designs(basket/umbrella) Rapid activation of trials Committee with stakeholders | PMID:3204894141 PMID: 3224006842 |

| Physician barriers | Incentivize Educate Flexible institutional policies | AYA champions AYA tumor boards Incentives Educational opportunities | PMID: 2221313426 PMID: 2466935413 PMID: 3600667843 |

| Patient convenience | Make it easy for patient to get to the trial Take trial to patient Education regarding trials and resources | Patient navigation Community engagement Educational initiatives Social work support | PMID: 3878547438 PMID: 3429761135 PMID: 3648042544 PMID: 3490540545 PMID: 3060622446 PMID: 2917093047 |

| Institutional barriers | Policies that are flexible Age restrictions Standard operating procedures Channels of communication between peds and medical oncology | Incentivize institutions/scorecard AYA specific pathways for intake Screening procedures for enrollments | PMID: 3608985928 PMID: 3392671012 PMID: 3526464220 PMID: 3825291148 |

| Barrier themes . | Strategies that can address barriers . | Examples of intervention . | Exemplar papers/trials (PubMed) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication amongst members of team | Forums to discuss cases Institutional policies Identifying unique AYA care Working groups | Tumor boards AYA champions AYA programs AYA working groups | PMID:3222270940 PMID: 3526464220 PMID: 3207778219 |

| Regulatory barriers | Share resources Assess workload/budget and staffing Stakeholder engagement | Shared IRB/central IRB Novel trial designs(basket/umbrella) Rapid activation of trials Committee with stakeholders | PMID:3204894141 PMID: 3224006842 |

| Physician barriers | Incentivize Educate Flexible institutional policies | AYA champions AYA tumor boards Incentives Educational opportunities | PMID: 2221313426 PMID: 2466935413 PMID: 3600667843 |

| Patient convenience | Make it easy for patient to get to the trial Take trial to patient Education regarding trials and resources | Patient navigation Community engagement Educational initiatives Social work support | PMID: 3878547438 PMID: 3429761135 PMID: 3648042544 PMID: 3490540545 PMID: 3060622446 PMID: 2917093047 |

| Institutional barriers | Policies that are flexible Age restrictions Standard operating procedures Channels of communication between peds and medical oncology | Incentivize institutions/scorecard AYA specific pathways for intake Screening procedures for enrollments | PMID: 3608985928 PMID: 3392671012 PMID: 3526464220 PMID: 3825291148 |

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Caroline Hesko: no competing financial interests to declare.

Jessica Heath: no competing financial interests to declare.

Michael E. Roth: no competing financial interests to declare.

Nupur Mittal: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Caroline Hesko: nothing to disclose.

Jessica Heath: nothing to disclose.

Michael E. Roth: nothing to disclose.

Nupur Mittal: nothing to disclose.