Abstract

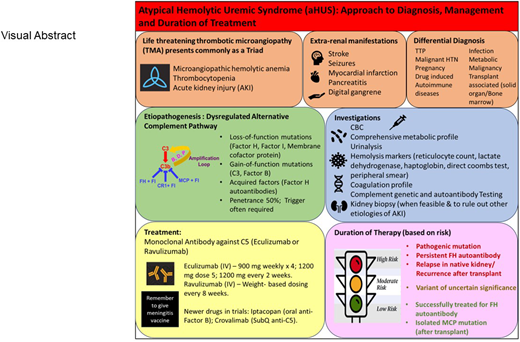

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a thrombotic microangiopathy typically characterized by anemia, thrombocytopenia, and end-organ injury. aHUS occurs due to endothelial injury resulting from overactivation of the alternative pathway of the complement system. The etiology of the dysregulated complement system is either a genetic mutation in 1 or more complement proteins or an acquired deficiency due to autoantibodies. Over the past decade, advancements in our understanding of the role of complement in the pathophysiology of aHUS as well as the availability of anticomplement drugs has been a game-changer for our patients. These drugs have revolutionized the clinical course, outcome, and prognosis of this disease. Therefore, all patients in whom aHUS is suspected should undergo testing for complement genetic variants and autoantibodies. In approximately 30% to 40% of patients, a genetic variant of uncertain significance (VUS) may be identified. Such patients should undergo further testing to define the significance of the VUS. A combination of antigenic, functional, and biomarker analyses can assist in establishing the significance of the variants and thereby define the etiology in most patients. These analyses will also help to determine the duration of treatment based on the individual's genetic alteration. This review aims to shed light on the diagnosis and management of aHUS and discusses how to stratify patients to determine who can safely discontinue anticomplement therapy.

Learning Objectives

Understand the etiology of aHUS with a focus on complement genetics and genetic interpretation

Learn how to risk stratify patients to determine treatment duration

CLINICAL CASE

A 41-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of worsening shortness of breath and lower extremity edema. His symptoms started 4 days prior to presentation when he developed an upper respiratory infection that led to excessive fatigue, decreased urine output, shortness of breath, and swelling in his legs. He was an architect and had no problems performing his job earlier that week. He followed up with his primary care physician yearly and never had these symptoms before. On admission, he was markedly hypertensive (blood pressure 210/160) and hypoxic (oxygen saturation in the mid-80s on room air). Laboratory findings were significant for anemia (hemoglobin, 7 g/dl), thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 56 000/µl), elevated lactate dehydrogenase (3195 U/L), low haptoglobin (<10 mg/dl), and acute kidney injury (creatinine 14.2 mg/dl; baseline 0.9 mg/dl). The peripheral smear showed 8 to 10 schistocytes/high-power field. ADAMTS13 activity was normal. Complement C3 was 89 mg/dl (normal range 90-180 mg/dl) and C4 was 26 mg/dl (normal range, 10-40 mg/dl). He underwent 2 to 3 sessions of plasma exchange while waiting for the ADAMTS13 results. Genetic testing was sent. Eculizumab was initiated when the ADAMTS13 activity came back normal. Hematological parameters started improving after the second dose of eculizumab; however, renal function remained poor and dialysis was initiated. He was started on multiple medications for hypertension. Four weeks later, he was seen in clinic and reported severe ongoing fatigue requiring assistance with activities of daily living. He had been unable to go back to work.

Introduction

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a prototypical complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).1 The disease is life threatening and typically characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150 × 109/L), and end-organ damage, with kidneys being the predominant organ involved, although extrarenal manifestations (such as stroke, seizures, and cardiovascular complications) may also occur.1 MAHA often presents as a hemoglobin level <10 g/dL, a serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level >1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and an undetectable haptoglobin. Coombs test is negative and schistocytes may be present on peripheral smear. aHUS can also present with less extreme values and may be renal limited (without hematological manifestations) in some cases. The reported incidence of renal-limited TMAs is approximately 38% to 45%, although the true incidence is unknown due to disparate rates of kidney biopsy.2,3

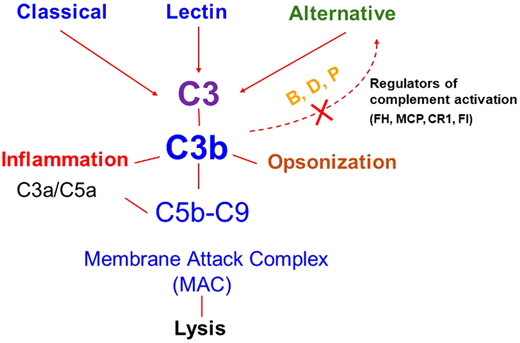

The major defect underlying aHUS is a dysregulated complement system4,5 (Figure 1). Therefore, the term complement- mediated TMA has also been proposed as an alternative for aHUS in an effort toward a more etiology/mechanism-based nomenclature.6 The most common etiology of a dysregulated complement system in aHUS/complement-mediated TMA is a genetic mutation in a regulator of the alternative pathway of the complement system [such as in factor H (FH), factor I (FI), or membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46)]. These are loss-of-function mutations that can lead to a quantitative defect (protein not being made) or a qualitative defect (protein is made but is dysfunctional).5,7 Less frequently, a gain-of-function mutation in a complement activator (C3, factor B) is identified. Genetic variants may be identified in approximately 40% to 60% of patients with aHUS. Acquired deficiencies in the form of autoantibodies against FH may also occur and are often associated with a homozygous deletion in CFHR1 and CFHR3 (complement FH-related 1 and 3).8,9 The incidence of FH autoantibodies is reported to be approximately 10% in the US and European cohorts (including both children and adults).8,9 A much higher incidence of these autoantibodies (up to 50%) has been reported in the Indian aHUS cohorts.10 Various theories have been proposed for the higher incidence in the Indian cohort.11 FH autoantibodies have been shown to impair the function of FH and thereby cause dysregulation of the alternative pathway.12 Of note, approximately 10% of affected patients carry more than 1 variant, or a risk of polymorphism, suggesting that the disease in these cases may result from an additive effect of several genetic factors.13 Disease penetrance is approximately 50%, further suggesting that despite an underlying genetic etiology, an environmental trigger is often needed in most cases to manifest disease.14 These triggers may include infections, drugs, pregnancy, malignancy, autoimmune disease, or kidney transplant.15-17 However, in many cases, the precipitating event may not be apparent.

Complement activation pathways. Activation of the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways results in the generation of C3 convertases that cleave C3 to C3b (which deposits on the cell surface) and C3a (an anaphylatoxin that recruits and activates effector cells). C3b deposition may rapidly amplify through a positive feedback loop (shown by the dotted line). C3b may also trigger activation of C5 through generation of C5 convertase, which cleaves C5 and results in the generation of C5a (an anaphylatoxin) and assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC; C5b-9). The key regulators of the amplification or feedback loop include factor H (FH), factor I (FI), membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46), and complement receptor 1 (CR1, CD35). Excessive activation via this loop secondary to a decrease in regulatory activity or a gain of function in a component like C3 or factor B due to genetic variants in these proteins predisposes to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. B, factor B; D, factor D; P, properdin. Reproduced from Java.27

Complement activation pathways. Activation of the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways results in the generation of C3 convertases that cleave C3 to C3b (which deposits on the cell surface) and C3a (an anaphylatoxin that recruits and activates effector cells). C3b deposition may rapidly amplify through a positive feedback loop (shown by the dotted line). C3b may also trigger activation of C5 through generation of C5 convertase, which cleaves C5 and results in the generation of C5a (an anaphylatoxin) and assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC; C5b-9). The key regulators of the amplification or feedback loop include factor H (FH), factor I (FI), membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46), and complement receptor 1 (CR1, CD35). Excessive activation via this loop secondary to a decrease in regulatory activity or a gain of function in a component like C3 or factor B due to genetic variants in these proteins predisposes to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. B, factor B; D, factor D; P, properdin. Reproduced from Java.27

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations in aHUS reflect ischemic organ dysfunction occurring due to endothelial injury and microthrombi formation in small blood vessels. Acute kidney injury is almost always seen with aHUS and is often more severe than in other TMAs and reflects the consequences of ischemia in the kidney. Renal presentation can vary across patients, with some presenting as renal-limited TMA diagnosed only on a kidney biopsy, without any hematological manifestations.2,18 Extrarenal manifestations may include stroke, seizures, myocardial infarction, hepatitis, pancreatitis, or digital gangrene.19 Thrombocytopenia is due to platelet consumption by thrombi in the microcirculation. Microangiopathic hemolysis is caused by the passage of blood through the damaged capillaries and arterioles occluded by thrombi. Reticulocyte counts are elevated and the peripheral smear reveals schistocytes. Other indicators of intravascular hemolysis include elevated LDH due to cell lysis and tissue ischemia, increased indirect bilirubin, and low haptoglobin level. The Coombs test is negative. Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, and coagulation factors are usually normal.

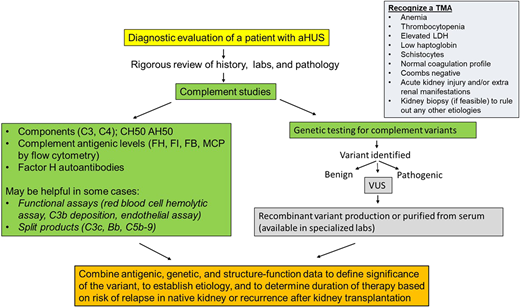

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a TMA is commonly made based on clinical features and laboratory findings (Figure 2). Therefore, evaluation should include a complete blood count, renal function panel, urinalysis, and urine protein quantification. Laboratory studies evaluating for MAHA should include a reticulocyte count, LDH, haptoglobin, direct Coombs test, coagulation profile, and a peripheral smear. Serum methylmalonic acid, homocysteine, vitamin B12, and folate levels should also be checked to rule out B12 deficiency, which can present as a TMA. In the presence of classic clinical and laboratory features, a kidney biopsy is not necessary to make a diagnosis and may not be feasible due to thrombocytopenia. However, in select cases (such as in renal-limited TMA), a biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. In other cases, it may be performed to evaluate the extent of organ damage and to rule out other etiologies of kidney failure. Pathologically, the hallmark feature of TMA is the presence of fibrin thrombi within the glomeruli.20 These thrombi typically resolve in 2 to 3 weeks. TMA may also present without overt thrombosis (often described as microangiopathy without thrombosis). Features of nonthrombotic TMA include endothelial swelling and mesangiolysis (in active lesions), duplication of the glomerular basement membrane (in chronic lesions), and accumulation of fluffy material in the subendothelium. When arteries are involved, myxoid intimal thickening and concentric myointimal proliferation (onion-skinning) may be seen, which also often correlates to malignant hypertension. All patients where the etiology of TMA is suspected to be due to aHUS should undergo a comprehensive evaluation to screen for complement system abnormalities as outlined below.

Diagnostic algorithm with recommended complement testing and steps to define clinical significance of genetic variants in a patient with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). AH50, alternative pathway activity; CH50, total hemolytic activity; FB, factor B; FH, factor H; FI, factor I; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Diagnostic algorithm with recommended complement testing and steps to define clinical significance of genetic variants in a patient with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). AH50, alternative pathway activity; CH50, total hemolytic activity; FB, factor B; FH, factor H; FI, factor I; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Antigenic levels

Serum antigenic levels of C3, C4, and ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 13) should be tested in all patients.21 A low C3 is seen in 30% to 50% of patients, whereas C4 is expected to be normal in most patients.22 However, patients who harbor FH autoantibodies may have a low C4 due to the formation of antigen-antibody complexes leading to activation of classical complement pathway. Importantly, a normal C3 does not rule out aHUS since C3 is also an acute-phase protein. Evaluation of aHUS patients should also include measurement of serum (or EDTA plasma) concentration of FH, FI, FB, and FH autoantibodies as well as MCP expression on leukocytes by flow cytometry. Because most patients with aHUS harbor a heterozygous mutation in 1 of the complement genes, patients in whom the mutant protein is not expressed would be expected to have a 50% serum antigenic level (for example, half-normal levels of FH in the case of a heterozygous mutation in CFH). Low FH levels have also been reported in approximately 30% of patients with FH autoantibodies, although there was no correlation between FH levels and FH autoantibody titres.9

Sequencing for genetic variants

All patients with suspected aHUS should also undergo testing for genetic mutations. Most CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) and CAP (College of American Pathologists)-certified labs conduct the clinically validated next-generation sequencing-based complement-mediated disease panel. This panel currently consists of 15 genes (ADAMTS13, C3, CD46, CFB, CFH, CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, CFHR4, CFHR5, CFI, DGKE, THBD, MMACHC, and PLG). CFHR3-CFHR1 copy number and other hybrid deletions should also be assessed using multiplex ligation- dependent probe amplification. Any identified genetic variants are reported according to Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature and classified based on the guidelines established by the joint consensus of the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association of Molecular Pathology.23 Based on these standards, variants are classified as 1 of 5 categories—pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variant of uncertain clinical significance (VUS), likely benign, or benign.

Interpreting results

When a variant is reported as “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic,” its ability to cause dysregulation of complement activation is clear.24-27 However, only 20% to 30% of identified mutations are reported as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, with a majority being reported as VUS. These VUS pose a challenge for clinical management and should undergo further investigation in specialized laboratories that can conduct functional and structural analyses to determine the significance of the variant.25-30 Furthermore, patients in whom no genetic variant is identified may need evaluation for other etiologies of a TMA. Such patients may also be considered for whole-exome sequencing to ascertain cause of disease and potentially identify additional genetic abnormalities not picked up by the disease-specific panel. Another area of future research also involves defining the clinical relevance of common polymorphisms identified in complement proteins in aHUS. Comprehensive genetic testing and interpretation of results is critical since the risk of recurrence or relapse in aHUS often depends on the underlying complement abnormality.

Management

There are 2 C5 inhibitors that are currently available and FDA approved for aHUS: eculizumab and ravulizumab.31-33 Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against complement C5. The drug binds to and blocks the cleavage of C5 into C5a and C5b, thereby preventing formation of the MAC, C5b-9. Since MAC is implicated in causing endothelial injury in aHUS, preventing its formation, limits ongoing injury. Ravulizumab is a long-acting monoclonal antibody against C5. It has been engineered from eculizumab by altering 4 amino acids. These amino acid changes do not affect the binding of ravulizumab to C5 in serum but allow it to dissociate from C5 in the acidified endosome (pH 6.0), resulting in an augmented efficiency of neonatal Fc receptor–mediated recycling of ravulizumab. Thus, ravulizumab has an increased half-life of approximately 52 days compared with approximately 11 days for eculizumab and therefore can be administered every 8 weeks vs eculizumab, which is given every 2 weeks. Because these drugs act downstream of C3, they preserve the autoimmune protective and immune-enhancing proinflammatory functions of the opsonin C3b and the anaphylatoxin C3a. Treatment should be initiated early to offer the best chance to recover kidney function in patients with aHUS.

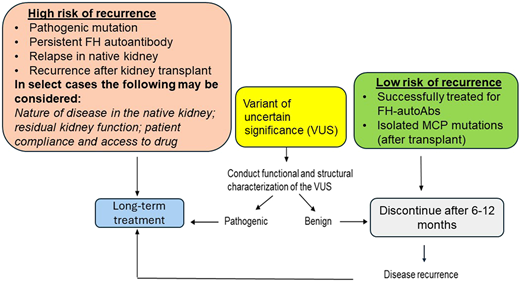

The optimal duration of anticomplement therapy in patients with aHUS is not entirely clear. There are no controlled trials to define the criteria for discontinuation of eculizumab, although several recent publications have reported the experience from various groups.34-37 Most of these publications and our own experience has shown that the risk of relapse and recurrence is high in patients who carry genetic variants. Our own protocol is shown in Figure 3. We typically continue lifelong treatment in moderate- to high-risk patients. For patients with a VUS, the duration of treatment is determined on a case-by-case basis based on structure-function analysis of the variant. For patients at low risk, we discontinue treatment after 6 to 12 months with close monitoring per our protocol.

Recommended duration of treatment of aHUS based on risk stratification. FH, factor H; MCP, membrane cofactor protein.

Recommended duration of treatment of aHUS based on risk stratification. FH, factor H; MCP, membrane cofactor protein.

In patients on anticomplement therapy, we measure total hemolytic complement (CH50) before each dose of eculizumab for the first 4 doses to evaluate effectiveness of complement blockade; patients with complete suppression should have a CH50 of <10%. If CH50 is not <10%, some patients may require a change in dosing or frequency of the drug. Measurement of CH50 can also confirm whether dose adjustment is indicated in patients not responding to the initial dose of eculizumab.

Most patients tolerate the drugs well, although one major concern with use of anticomplement therapy is a life-threatening infection with Neisseria meningitidis (owing to blockage of the terminal complement pathway).38 Patients should receive both the MenACWY and MenB vaccination to prevent these infections. Ideally, the vaccines should be given at least 2 weeks before administering the first dose of the complement inhibitor; however, if there is not enough time to wait for immune response, appropriate antibiotics (penicillin or fluoroquinolone) should be used for at least 14 days. We usually give antimicrobial prophylaxis for the duration of eculizumab treatment to reduce the risk for meningococcal disease and the concern that patients with chronic kidney disease may not mount an adequate response to vaccinations. A booster dose of MenACWY vaccine should be administered every 5 years, and for MenB, a booster is given 1 year after series completion and then every 2 to 3 years thereafter, for the duration of complement inhibitor therapy (https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/hcp/clinical-guidance/complement-inhibitor.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/clinical/eculizumab.html). It is important to remember, however, that neither vaccination nor antimicrobial prophylaxis can prevent all cases of meningococcal disease. Therefore, symptoms suggestive of a bacteremia or septicemia should necessitate urgent investigation and antibiotic therapy.

Several other drugs targeting complement proteins at various levels in the pathway are also in development for TMAs39,40 (Table 1). These novel complement inhibitors include crovalimab (anti-C5), nomacopan (anti-C5), pegcetacoplan (anti-C3), narsoplimab (mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease [MASP] 2 inhibitor), and iptacopan (anti-factor B). Prospective, randomized controlled trials are required to investigate the utility of these various anticomplement therapies in aHUS.

Currently approved and newer drugs in trials for thrombotic microangiopathies

| Name of the drug . | Target . | Route . | ClinicalTrials.gov . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eculizumab | Anti-C5 | SC | FDA approved; NCT03518203 (HSCT-TMA) |

| Ravulizumab | Anti-C5 | SC | FDA approved; NCT04543591 (adult HSCT-TMA), NCT04557735 (pediatric HSCT-TMA), NCT04570397 (COVID-19) |

| Crovalimab | Anti-C5 | SC | NCT04861259 (adult aHUS), NCT04958265 (pediatric aHUS) |

| Nomacopan | Anti-C5 and leukotriene B4 | SC | NCT04784455 (transplant-associated TMA) |

| Iptacopan | Anti-factor B | Oral | NCT04889430 (adult aHUS) |

| Pegcetacoplan | Anti-C3 | SC | NCT05148299 (HSCT-TMA) |

| Narsoplimab | MASP 2 inhibitor | IV | NCT05855083 (pediatric HSCT-TMA) |

| Name of the drug . | Target . | Route . | ClinicalTrials.gov . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eculizumab | Anti-C5 | SC | FDA approved; NCT03518203 (HSCT-TMA) |

| Ravulizumab | Anti-C5 | SC | FDA approved; NCT04543591 (adult HSCT-TMA), NCT04557735 (pediatric HSCT-TMA), NCT04570397 (COVID-19) |

| Crovalimab | Anti-C5 | SC | NCT04861259 (adult aHUS), NCT04958265 (pediatric aHUS) |

| Nomacopan | Anti-C5 and leukotriene B4 | SC | NCT04784455 (transplant-associated TMA) |

| Iptacopan | Anti-factor B | Oral | NCT04889430 (adult aHUS) |

| Pegcetacoplan | Anti-C3 | SC | NCT05148299 (HSCT-TMA) |

| Narsoplimab | MASP 2 inhibitor | IV | NCT05855083 (pediatric HSCT-TMA) |

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Two months after the initial presentation, the patient started making urine again. Creatinine came down to 4 mg/dl. Dialysis was discontinued. Six months later, creatinine further improved to 2 mg/dl. Hematological parameters had normalized as mentioned earlier and stayed stable. Genetic testing revealed a pathogenic splice mutation in CFH and a VUS in CFI (P64L). Further testing for serum antigenic level showed that these variants resulted in low FH and FI levels. Functional analyses further demonstrated that the CFI variant resulted in defective complement regulatory activity with MCP and complement receptor 1 (Java unpublished data). Given these analyses, the CFI variant was “likely pathogenic” and not a VUS. The patient was continued on eculizumab and later switched to ravulizumab. We decided to keep the patient on treatment indefinitely for several reasons: (1) This was a young patient with an aggressive presentation in the presence of minimal trigger, and he carried pathogenic mutations in 2 important complement regulators, FH and FI; (2) Patients who carry mutations that cause quantitative defects (low antigenic levels) in CFH are most likely to relapse after discontinuation of therapy; and (3) The patient's kidney function did not recover completely, and he had a new baseline creatinine of 2 mg/dl. If he develops recurrent disease in the absence of treatment, it may be enough to lead to end-stage kidney disease. However, if this patient did not carry any known pathogenic mutations and his kidney function had recovered fully, we would have considered stopping treatment.

Conclusion

Complement system is an integral part of our innate immune system that provides us with a powerful defense against infections and microbes. Because of its rapid amplifying capacity, regulators of complement activation are required to keep it in check. In complement-mediated diseases, such as aHUS, the system gets dysregulated and attacks healthy host cells, leading to endothelial injury and microthrombi formation. Over the last decade, elucidation of the role of genetic mutations in complement proteins, and the availability of anticomplement drugs, has significantly advanced our understanding of aHUS and outcomes for our patients. However, many challenges remain: (1) There is a lack of a biomarker that can aid in rapid diagnosis of aHUS and/or help to differentiate it from other TMAs; (2) The pathophysiology of why some patients present with renal-limited TMA remains unclear; and (3) There is no uniform consensus on treatment duration. Although discontinuation of anticomplement therapy is feasible in some patients, prospective studies are required to better define parameters that are predictive of relapse. Nevertheless, the future looks very promising for the further delineation of complement disease associations and for novel therapeutic agents, which can be tailored to the right patient based on each patient's specific alteration.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Anuja Java reports serving on the scientific advisory boards of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, and Novartis International AG and as a consultant for Dianthus Therapeutics and Aurinia Pharmaceuticals. She is a principal investigator for Apellis Pharmaceuticals and Novartis International AG and receives royalty from UpToDate.

Off-label drug use

Anuja Java: Nothing to disclose.