Abstract

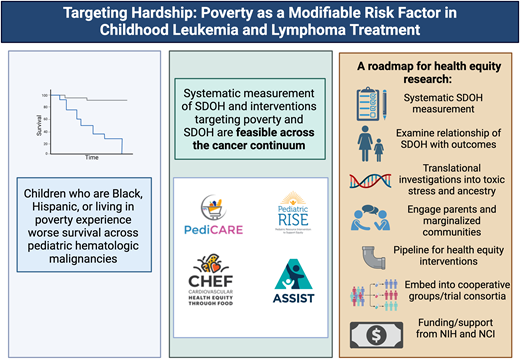

Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic survival disparities have been well-demonstrated across population-based and clinical trial datasets in pediatric hematologic malignancies. To date, these analyses have relied on trial-collected data such as race, ethnicity, insurance, and zip code. These exposures serve as proxies for factors such as structural racism, genetic ancestry, and adverse social determinants of health (SDOH). Systematic measurement of SDOH and social needs—and interventions targeting these needs—are feasible in pediatric oncology. We use these data to present a roadmap for the next decade of health equity research to identify actionable mechanisms and develop a portfolio of interventions to advance equitable outcomes across pediatric hematologic malignancies.

Learning Objectives

Describe a framework for advancing health equity in pediatric oncology

Describe examples of interventions targeted to social determinants of health with a focus on targeting poverty and unmet social needs

CLINICAL CASE

You are seeing a 3-year-old child with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who was recently discharged after completion of induction chemotherapy. Meeting her family, you learn that she is 1 of 3 children. Her parents emigrated from Mexico, and her mother had to quit her job as a cashier to be at her daughter's bedside during hospitalizations and to bring her to upcoming frequent appointments. The child is currently enrolled on Medicaid; her family is struggling to buy food for their family and is behind on rent for their 1-bedroom apartment.

As you look ahead to the next 2 years of therapy, you wonder how these factors will affect this child's care. Is she at risk of worse outcomes? If so, which factors drive that risk? And most importantly, what—if anything—can we as clinicians do about them?

Introduction

In the era of contemporary therapy, the vast majority of children with pediatric hematologic malignancies will survive their cancer due to significant medical advances refined in cooperative group trials. Despite these advances, not all children have equitable opportunities for cure. Children who are Black, Hispanic, or living in poverty experience inequitable survival outcomes across pediatric hematologic malignancies.

Despite enrollment on clinical trials, Black and Hispanic children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated in Children's Oncology Group (COG) clinical trials experienced inferior survival outcomes compared to non-Hispanic White children.1,2 In ALL, insurance partially mediates the relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and survival, while in AML, higher disease burden and acuity at presentation requiring intensive care unit (ICU)-level care may contribute to early mortality.3,4 Similar survival disparities have been observed among children with ALL treated in Dana-Farber Consortium trials living in high-poverty zip codes.5 While frontline trial enrollment has mitigated survival disparities for Black and Hispanic children and adolescents/young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma, they experience higher rates of postrelapse mortality, suggesting disparities in postrelapse care.6

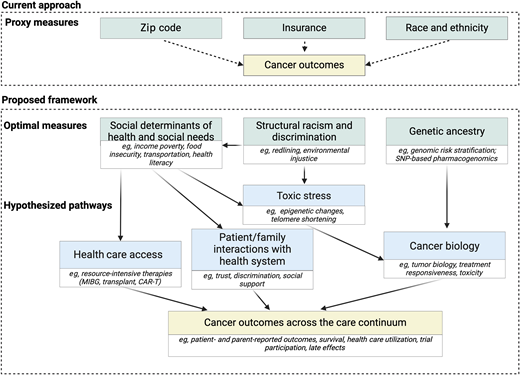

These data demonstrate survival disparities by race, ethnicity, and proxied socioeconomic factors across diseases with variable prognoses; by inpatient vs outpatient care; and despite standardized care on clinical trials. Yet, limited by available collected data, analyses have focused on description (Figure 1). There is a pressing need to shift research away from description and toward mechanisms and interventions. We present a roadmap for the next decade of health equity research focused on identifying the mechanisms driving inequitable outcomes and opportunities to address them. We specifically delve into the evidence base for poverty-targeted interventions addressing unmet social needs in pediatric oncology.

Proposed framework to measure drivers of disparities. CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; MIBG, iodine meta- iodobenzylguanidine therapy; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Proposed framework to measure drivers of disparities. CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; MIBG, iodine meta- iodobenzylguanidine therapy; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Systematic measurement of self-reported social determinants of health (SDOH) and social needs

While race, ethnicity, and proxied socioeconomic status measures such as zip code and insurance can identify disparities, they do not adequately identify underlying mechanisms that can be targeted in the clinical setting. Race and ethnicity are constructs that proxy exposures to structural racism and racial discrimination; they may separately proxy genetic ancestry. While insurance and zip code can be indicators of health care access, as proxies for individual-level exposures such as low income or education, they are prone to misclassification.7-9 Identification of actionable targets for intervention requires measurement of self-reported individual- and family-level SDOH and social needs.

Communities impacted by structural racism disproportionately experience adverse SDOH—the conditions in which individuals live, learn, play, grow, and work. Social needs are individual-level modifiable factors arising from adverse SDOH that can provide targets for intervention. As 1 example, household material hardship (HMH) is a social need measure well-studied in pediatric oncology and defined as lack of consistent access to adequate food, housing, transportation, or utilities.10

The feasibility of systematic SDOH screening, including social needs such as HMH, across the care continuum, from cancer diagnosis to relapse/progression and survivorship,11 has now been demonstrated across multiple contexts including among historically marginalized populations and in clinical trials. SDOH data have been successfully collected as embedded aims of national multicenter clinical trials including within the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium (NCT03020030) and Children's Oncology Group (NCT03126916, NCT03914625, NCT06172296) trials with >85% participation and minimal data missingness (<2% for HMH, the primary SDOH exposure of interest in each investigation).11,12 From these data, we have learned that approximately 1 in 3 children enrolled in national multicenter trials for de novo cancer experiences HMH,11,12 and 1 in 2 children with advanced cancer treated at a single, large volume center experiences HMH.13 Black and Hispanic families disproportionately experience HMH, with nearly 3 of 4 families reporting unmet social needs during their child's cancer care.14 These data provide proof of principle that SDOH data collection is highly feasible and that social needs are highly prevalent in pediatric oncology despite care at well-resourced centers with access to social workers, financial specialists, and resource specialists.

Examine the relationships between SDOH and child and family outcomes

Critical next steps in advancing health equity research include identifying associations between modifiable SDOH and child and family outcomes. In a recent study, HMH was independently associated with severe psychological distress among parents of children enrolled on a multicenter therapeutic phase 3 trial for de novo ALL.15 Compared to unexposed parents, HMH-exposed parents were twice as likely to experience severe psychological distress at trial enrollment and 5 times as likely 6 months into therapy. As data mature from this trial and others in which SDOH have been prospectively collected, future analyses will examine associations between adverse SDOH and child health outcomes including health care utilization, survival, and quality-of-life. Systematic SDOH data collection in future therapeutic clinical trials leverages existing trial data collection infrastructure, ensures nationally representative populations, and maximizes homogeneity of disease and treatment to facilitate the identification of SDOH exposures independently associated with outcomes. As such, trial-collected data can both elucidate mechanisms by which SDOH contribute to outcome inequities and identify SDOH targets for intervention.

Translational investigations to consider biology from a health equity lens

As health equity investigation enters the next decade, a focus on biology in addition to SDOH is key to understanding mechanisms driving inequities. Duffy null–associated neutrophil count is 1 example of a genetic ancestry–associated biological difference that may lead to clinical trial ineligibility and consequent disparities in trial diversity.16 Identifying mechanisms driving disparate outcomes for marginalized groups will require investigating potential contributory roles of both genetic ancestry and toxic stress. First, investigators should leverage trial-collected biology specimens to investigate the role of genetic ancestry in driving differential tumor biology and treatment toxicities. Examples include the higher frequency of risk-conferring IKZF1 alterations among pediatric patients of Hispanic ethnicity17 and the association of genetic ancestry with ALL subtypes and survival.18,19 Second, investigations should focus on the role of toxic stress, the mechanism by which severe and prolonged exposure to adverse SDOH lead to physiologic changes. Recent studies have identified DNA methylation changes associated with adverse SDOH among both childhood cancer survivors and healthy young adults.20,21 Further investigations of toxic stress in the context of pediatric oncology treatment resistance and toxicity may identify additional drivers of inequities.

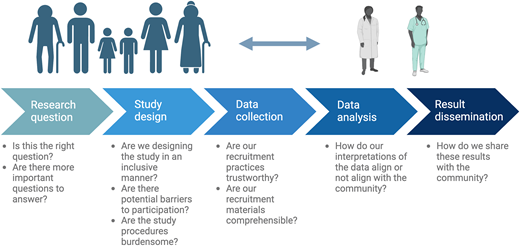

Engage historically marginalized parent and community perspectives across the continuum of research

Racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically marginalized families have been historically underrepresented in pediatric oncology research due to structural participation barriers. Extrapolating from data in the adult oncology context, underrepresentation has historically been blamed on distrust.22 A recent mixed-methods study of Black and Hispanic parents of children with cancer challenges this concept and found that Black and Hispanic parents express high trust in their oncology teams and are willing to enroll their children in pediatric oncology research and clinical trials if offered.23 Ninety-four percent of families from historically marginalized communities approached for this study consented to participate, highlighting their willingness to engage in research. Qualitatively, parents named representation of their experiences and voices in research as a key motivator to research participation. These data provide proof-of-concept that historically marginalized families can and should be engaged in pediatric oncology research. Distrust cannot not be used as an excuse for underrepresentation, and underrepresentation should prompt critical examination into participation and retention.

Investigators should prioritize the perspectives of historically marginalized parents and communities across the research continuum, including in the selection of relevant research questions, study and intervention design, data interpretation, and framing/dissemination of the results (Figure 2). These perspectives should be incorporated across the continuum from clinical trial inception to the real-world implementation of efficacious therapies to ensure that advances do not widen inequities for historically marginalized groups and that potential barriers to equitable uptake are proactively addressed. Finally, engaging voices from historically marginalized groups requires consideration of barriers to research partnerships, such as timing, mode and frequency of meetings (virtual vs in person; work hours vs evenings), transportation, and childcare; thus, providing adequate support and compensation to facilitate participation is required.

Establish a pipeline for health equity intervention development and testing

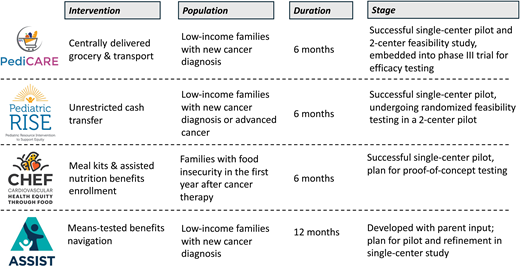

Interventions addressing poverty, SDOH, and social needs improve child outcomes in general pediatrics. Specifically, systematic screening and resource navigation decrease unmet needs, improve child health, increase on-time vaccination and preventative health visits, and decrease emergency department visits.24-26 Building on these foundational approaches to develop a portfolio of supportive care health equity interventions for the subspecialty setting has the potential to improve cancer outcomes. Reductions in toxicity and improvements in survival for pediatric hematologic malignancy have been successfully realized over the past decades with risk-stratified treatment and risk-stratified supportive care (eg, antimicrobial prophylaxis, leucovorin rescue). A similar framework for developing supportive care health equity interventions that target high-risk SDOH and social needs modeled on drug trial development has now been established and includes health equity intervention: 1) pilot and refinement in a single-center trial, 2) pilot feasibility and signal-finding in a 2-center trial, and 3) randomized efficacy evaluation in a multicenter clinical trial with the ultimate goal of real-world implementation of efficacious interventions.

PediCARE

The Pediatric CARE (Cancer Resource Equity) intervention targets food and transportation insecurities with provision of centrally delivered grocery and transportation resources to families with HMH for 6 months after a new cancer diagnosis. This intervention builds on systematic social needs screening and referral to community-based resources in general pediatrics24-26 by directly providing resources to address the acute and life-threatening nature of childhood cancer. In a single-center pilot study, PediCARE was refined based on parent feedback to optimize intervention duration (from 3 to 6 months), dose (broadened scope of transportation support), and intervention delivery logistics.27 Feasibility of multicenter, randomized administration of the refined PediCARE was subsequently demonstrated in a 2-center pilot of with 100% consent to enrollment and randomization and 0% attrition over 6 months; all families randomized to PediCARE successfully received resources.28 PediCARE is currently being evaluated for efficacy in a randomized phase 3 trial as an embedded aim of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute 23-001, a phase 3 multicenter trial for de novo ALL.

PediRISE

The Pediatric RISE (Resource Intervention to Support Equity) intervention targets income poverty by providing an unrestricted cash transfer to families of children with cancer with annual household income <200% of the federal poverty threshold. RISE builds on population-level and general pediatric data demonstrating that direct financial support—termed cash transfer—is feasible and associated with improved child and family outcomes.29-35 RISE was refined in a single-center pilot among families of children with newly diagnosed or advanced cancer with high acceptability (95% participation and 0% attrition). Intervention refinement included an increase in the standardized dollar amount provided to account for treatment-related financial toxicity. The feasibility of the refined RISE intervention is currently being evaluated in a 2-center randomized pilot of children with newly diagnosed cancer.

CHEF

The CHEF (Cardiovascular Health Equity through Food) intervention targets food insecurity among families in the first year following completion of cancer-directed therapy with provision of meal kits (fresh ingredients paired with recipes) and assisted nutrition benefits enrollment. This intervention model is based on general pediatric and internal medicine data that “food is medicine” interventions, which provide food directly to patients to address food insecurity and prevent or treat diet-sensitive chronic illness, improve food security status, diet quality, and cardiometabolic risk.36-38 CHEF was refined in a single-center pilot with high acceptability (100% participation, 0% attrition). Refinements in response to parent feedback included extended intervention duration (3 to 6 months) and need for a step-down period of less-intensive food support (grocery gift cards for months 3-6). CHEF will undergo proof-of-concept testing to evaluate its signal of impact on cardiovascular-relevant outcomes (dietary quality, food security status, and cardiometabolic risk condition control) in an upcoming single-site study.

ASSIST

The ASSIST (Assisted Benefits Navigation Support) intervention targets HMH by providing real-time, centralized, means-tested benefits navigation and enrollment assistance for families of children with cancer. This intervention model is based on population-level data that benefits such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program; Women, Infants, and Children Program; and the Earned Income Tax Credit improve maternal and child health.39,40 ASSIST was developed with the input of a racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse cohort of parents who identified the need for systematic social needs evaluation and hands-on support accessing resources due to limited bandwidth and time during their child's cancer care. ASSIST will undergo pilot and refinement testing in an upcoming single center study.

Developing and evaluating health equity interventions that target multiple SDOH across the pediatric oncology care continuum is feasible (Figure 3). Just like drugs, efficacy evaluation of novel health equity interventions requires sample sizes achievable only in the pediatric cooperative group setting given the rarity of childhood cancer. Development of an evidence-based portfolio of supportive care health equity interventions will require the equivalent of an early-phase drug pipeline infrastructure to refine interventions and subsequent active support from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and pediatric cooperative groups to evaluate equity intervention efficacy in the existing clinical trials research infrastructure, given that no similar federally supported infrastructure dedicated to SDOH-targeted interventions exists.41

Intervention models targeting social needs in pediatric oncology that demonstrate feasibility and provide a framework for future interventions.

Intervention models targeting social needs in pediatric oncology that demonstrate feasibility and provide a framework for future interventions.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

While the prognosis for a 3-year-old with standard risk leukemia is excellent, data suggest that this child is at risk for inferior outcomes based on her public insurance.1 The family-reported HMH (food and transportation insecurity) increases her parents' risk for severe psychological distress during therapy with downstream implications for the child. The identification and reassessment of these needs over the course of therapy and the subsequent connection to available resources are important first steps. Evidence-based intervention to mitigate her risks will rely on future translational and clinical investigation.

Conclusions

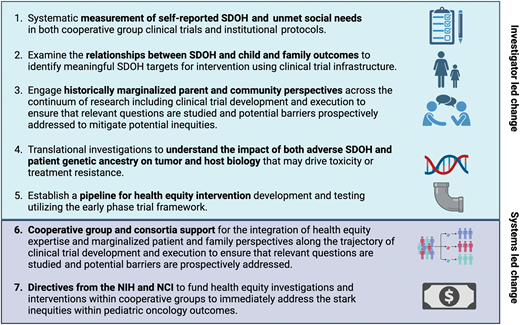

Pediatric oncologists are facile at molecular prognostication and risk-stratified therapy in hematologic malignancies; analogous consideration of SDOH as independent prognostic factors and targets for risk-stratified supportive care delivery is a next step to improve outcomes. Systematic evaluation of SDOH and development and evaluation of health equity interventions is feasible in pediatric hematologic malignancies. By embedding health equity investigation into all aspects of pediatric oncology research (Figure 4), investigators can identify mechanistic drivers of inequities and build a portfolio of interventions to eliminate outcome inequities across the cancer care continuum. True scalability and impact of such efforts will require explicit support, funding, and infrastructure from pediatric oncology cooperative groups, trial consortia, and the NCI. In the next decade, systematic integration of SDOH into risk stratification for pediatric hematologic malignancies combined with risk-stratified health equity intervention is necessary to complement disease-directed therapies and improve pediatric hematologic malignancy outcomes.

A roadmap for health equity research in pediatric oncology. NIH, National Institutes of Health.

A roadmap for health equity research in pediatric oncology. NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgment

Figures created with biorender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Puja J. Umaretiya: no competing financial interests to declare.

Rahela Aziz-Bose: no competing financial interests to declare.

Colleen Kelly: no competing financial interests to declare.

Kira Bona: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Puja J. Umaretiya: Nothing to disclose.

Rahela Aziz-Bose: Nothing to disclose.

Colleen Kelly: Nothing to disclose.

Kira Bona: Nothing to disclose.