Abstract

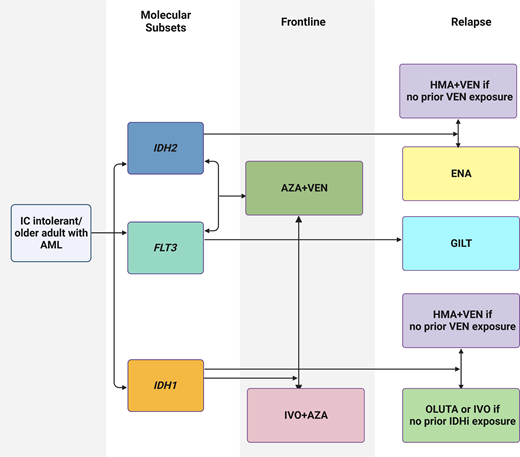

The routine use of next-generation sequencing methods has underscored the genetic and clonal heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), subsequently ushering in an era of precision medicine–based targeted therapies exemplified by the small-molecule inhibitors of FLT3, IDH1/IDH2, and BCL2. This advent of targeted drugs in AML has broadened the spectrum of antileukemic therapies, and the approval of venetoclax in combination with a hypomethylating agent has been a welcome addition to our AML patients unable to tolerate intensive chemotherapy. Mounting evidence demonstrates that molecularly targeted agents combined with epigenetic therapies exhibit synergistic augmented leukemic cell kill compared to single-agent therapy. With such great power comes greater responsibility in determining the appropriate frontline AML treatment regimen in a molecularly defined subset and identifying safe and effective combination therapies with different mechanisms of action to outmaneuver primary and secondary resistance mechanisms in AML.

Learning Objectives

Compare frontline treatment approaches in IC-ineligible IDH1-mutant AML and explain how to sequence targeted therapies upon relapse

Evaluate frontline AZA-VEN therapy and targeted treatment options for IC-ineligible AML patients with IDH2, FLT3, NPM1, or TP53 mutations

Introduction

The approval of venetoclax (VEN) and a hypomethylating agent (HMA; azacitidine [AZA] or decitabine) combination therapy for older adults (aged ≥75 years or not eligible to receive intensive chemotherapy [IC]) with newly diagnosed (ND) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) denotes a paradigm shift in the AML treatment landscape.1 In the registrational VIALE-A trial for ND AML patients unable to receive IC (median age, 76 years), AZA-VEN combination therapy showed significantly improved composite complete remission (CRc; CR + CR with incomplete hematologic recovery [CRi], 66.4% vs 28.3%) and overall survival (OS) rates (14.7 vs 9.6 months) compared to AZA-placebo.2 Long-term follow-up (43.2 months) of VIALE-A confirmed an ongoing survival benefit, albeit more pronounced in those who achieved measurable residual disease negativity.3

Nevertheless, this golden era of rationally targeted AML therapy is plagued by primary resistance and clonal evolution leading to adaptive resistance.4 Specifically, in AML patients receiving frontline VEN-based therapy, kinase-activating mutations such as FLT3-ITD and TP53 alterations appear to be the major drivers of adaptive drug resistance, while patients enriched for NPM1 and/or IDH1/IDH2 mutations appear particularly sensitive to VEN, with durable responses.5 Sequential single-cell sequencing of diagnosis- remission-relapse samples of AML patients treated with HMA-VEN has illuminated confounding patterns of treatment resistance such as the expansion or acquisition of new FLT3-ITD clones or the parallel outgrowth of triple-mutant FLT3-ITD/IDH1/NPM1 treatment-resistant subclones.5 Furthermore, the emergence of RAS pathway mutations appears to be the leitmotif of AML treatment failure across the spectrum of HMA-VEN,5 IDH inhibitors,6,7 and FLT3 inhibitors (FLT3i).8 In addition to the mutational spectrum and clonal hierarchy, other primary and acquired mechanisms of resistance, such as cell of origin/differentiation state (e.g., monocytic AML), pro- and antiapoptotic protein dynamics/BAX mutations, and mitochondrial metabolism alterations may also be at play.9 This innate and treatment-induced selective pressure on AML clones has prompted unresolved questions regarding the categorical frontline treatment approach; namely, do we combine, add on, or sequence HMA-VEN and molecularly targeted therapies? Here we present case studies that illustrate the genomic complexity of AML and how we approach treatment in different settings.

Clinical scenario: older adult with ND IDH1-mutant AML

Mr. X, a 79-year-old man who dislikes hospitals, presented with a white blood cell (WBC) count of 1.0 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 7.4 g/dL, and platelet count of 120 × 109/L during his periodic cardiac checkup. Bone marrow biopsy confirmed AML with 28% myeloblasts and trisomy 12, and molecular studies identified NPM1 (variant allele fraction [VAF], 40%), DNMT3A (VAF, 35%), and IDH1-R132C (VAF, 48%) mutations. What is the appropriate frontline treatment option for this patient?

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® version 3.2023 AML guidelines endorse either AZA-VEN or ivosidenib (IVO, an orally administered IDH1-targeted inhibitor) plus AZA as a category 1 recommendation (Table 1). Preclinical data have shown that IDH1/2-mutant cells exhibit BCL2 dependence, thus rendering them sensitive to VEN, a BCL2 inhibitor.10 In the pooled analysis of AZA-VEN studies,11 44 patients with ND AML (n = 498, 8%) harbored IDH1mut. Among those who received AZA-VEN (n = 33), the CRc and CR rate was 66.7% and 27%, respectively. Most patients achieved CR or CRi in the first cycle, the median duration of objective response (DoR) was 21.9 (95% CI, 7.8-NE [not estimable]) months, and median OS was 15.2 months (95% CI, 7.0-NE). In this pooled analysis of IDH1/2mut AML patients treated with AZA-VEN (n = 81), 87% had grade 3 or higher hematological adverse events (AEs); 42%, febrile neutropenia; and 46%, thrombocytopenia.11

Comparison of baseline demographics and efficacy outcomes in patients with ND IDH1mut AML treated on the pivotal registrational trials of VIALE-A (pooled analysis) and AGILE

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | AZA with VEN N = 33 . | IVO with AZA N = 72 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 76 (64-90) | 76 (58-84) |

| Response outcomes | ||

| Composite CR (CRc*) rate | 67% | 53% |

| CR rate | 27% | 47% |

| Duration of response (mo) | ||

| Median time to CRc (range) | 1.2 (0.8-8.1) | 4.0 (1.7-8.6) |

| Median duration of CRc (95% CI) | 21.9 (7.8-NE) | NE (13.0-NE) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | ||

| Median OS (95% CI) | 15.2 (7.0-NE) | 24 (11.3-34.1) |

| Estimated 12-mo survival probability (95% CI) | 57.6% (39.1-72.3) | ~ 64% |

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | AZA with VEN N = 33 . | IVO with AZA N = 72 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 76 (64-90) | 76 (58-84) |

| Response outcomes | ||

| Composite CR (CRc*) rate | 67% | 53% |

| CR rate | 27% | 47% |

| Duration of response (mo) | ||

| Median time to CRc (range) | 1.2 (0.8-8.1) | 4.0 (1.7-8.6) |

| Median duration of CRc (95% CI) | 21.9 (7.8-NE) | NE (13.0-NE) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | ||

| Median OS (95% CI) | 15.2 (7.0-NE) | 24 (11.3-34.1) |

| Estimated 12-mo survival probability (95% CI) | 57.6% (39.1-72.3) | ~ 64% |

IQR, interquartile range.

Here defined as CR plus CRi in VIALE-A (pooled analysis) and CR/CRh in AGILE. CR plus CRi in AGILE was 54%.

In the phase 3 AGILE trial, IVO (500 mg daily) plus AZA (parenterally for 7 days) was compared to AZA-placebo in ND, IC-ineligible IDH1mut AML patients.2 In the intention-to-treat population (n = 146), 72 patients received IVO-AZA: among those, the rate of CR or CR with partial hematological recovery (CRh) was 53%, including a CR rate of 47%. The median time to CR was 4.3 months (range, 1.7–9.2), and the median DoR was 22.1 months (95% CI, 13.0-NE). With a median follow-up of 12.4 months, median OS in the IVO-AZA arm was 24.0 months (95% CI, 11.3-34.1), compared to 7.9 months with AZA-placebo (P = .001). Among patients treated with IVO-AZA, 70% had grade ≥3 hematological AEs; 28%, febrile neutropenia; and 24%, thrombocytopenia. AEs of special interest (grade ≥3) included 10% QTc prolongation and 4% differentiation syndrome, which resolved with conservative management.2

In this case scenario, we will propose either AZA-VEN or IVO-AZA as a frontline treatment for IC-ineligible IDH1mut AML after carefully considering the patient's comorbidities and the AE profile of the treatment regimen. Depending on test availability and institutional turnaround time for molecular studies, practical issues may arise with obtaining IDH1 mutation status prior to initiating therapy, particularly in proliferative patients who may require more urgent treatment.

Relapsed/refractory IDH1-mutant AML

IVO or olutasidenib (OLU) is approved to treat relapsed/refractory (R/R) IDH1mut AML (Table 2).12 In the phase 1b study evaluating IVO in R/R IDH1mut AML,13 the rate of CR plus CRh was 30.4% (95% CI, 22.5-39.3), including a 21.6% CR rate in the primary efficacy population. With a median follow-up of 14.8 months (range, 0.2-30.3), the median duration of CR or CRh was 8.2 months (95% CI, 5.5-12.0), and the median OS was 8.8 months (95% CI, 6.7-10.2). AEs of special interest (grade ≥3) included QTc prolongation (7.8%) and IDH differentiation syndrome (3.9%). Of note, this study did not include patients exposed to VEN due to their contemporaneous approvals.13

Comparison of baseline demographics and efficacy outcomes in patients with R/R IDH1mut AML treated on the pivotal registrational trials of IVO and OLU

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | IVO N = 125 . | OLU N = 147 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 67 (18-87) | 71 (range, 32-87) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 27 (22) | 45 (31) |

| 1 | 64 (51) | 76 (52) |

| 2 | 32 (26) | 23 (16) |

| 3 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| AML type, n (%) | ||

| De novo | 83 (66) | 97 (66) |

| Secondary | 42 (34) | 50 (34) |

| Cytogenetic risk, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | – | 6 (4) |

| Intermediate | 66 (53) | 107 (73) |

| Poor | 38 (30) | 25 (17) |

| Missing/unknown | 21 (17) | 9 (6) |

| Co-mutations, n (%) | ||

| NPM1 | 24 (20) | 31 (21) |

| FLT3 | 9 (8) | 15 (10) |

| CEBPA | 3 (3) | <10% |

| Prior regimens, median (range) | 2 (1-6) | 2 (1-7) |

| VEN, n (%) | 0 | 12 (8) |

| HSCT, n (%) | 36 (29) | 17 (12) |

| Bone marrow blast percentage, median (range) | 56 (0-98) | 42 (4-98) |

| Response outcomes | ||

| Composite CR (CR plus CRh) rate | 30% | 35% |

| CR rate | 21% | 32% |

| Duration of response (mo) | ||

| Median time to CR/CRh (range) | 2.7 (0.9-5.6) | 1.9 (0.9-5.6) |

| Median duration of CR/CRh (95% CI) | 8.2 (5.5-12.0) | 25.9 (13.5-NE) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | ||

| Median OS (95% CI) | 8.8 (6.7-10.2) | 11.6 (8.9-15.5)* |

| Estimated 18-mo survival probability in patients with CR/CRh | 50% | 78% |

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | IVO N = 125 . | OLU N = 147 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 67 (18-87) | 71 (range, 32-87) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 27 (22) | 45 (31) |

| 1 | 64 (51) | 76 (52) |

| 2 | 32 (26) | 23 (16) |

| 3 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| AML type, n (%) | ||

| De novo | 83 (66) | 97 (66) |

| Secondary | 42 (34) | 50 (34) |

| Cytogenetic risk, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | – | 6 (4) |

| Intermediate | 66 (53) | 107 (73) |

| Poor | 38 (30) | 25 (17) |

| Missing/unknown | 21 (17) | 9 (6) |

| Co-mutations, n (%) | ||

| NPM1 | 24 (20) | 31 (21) |

| FLT3 | 9 (8) | 15 (10) |

| CEBPA | 3 (3) | <10% |

| Prior regimens, median (range) | 2 (1-6) | 2 (1-7) |

| VEN, n (%) | 0 | 12 (8) |

| HSCT, n (%) | 36 (29) | 17 (12) |

| Bone marrow blast percentage, median (range) | 56 (0-98) | 42 (4-98) |

| Response outcomes | ||

| Composite CR (CR plus CRh) rate | 30% | 35% |

| CR rate | 21% | 32% |

| Duration of response (mo) | ||

| Median time to CR/CRh (range) | 2.7 (0.9-5.6) | 1.9 (0.9-5.6) |

| Median duration of CR/CRh (95% CI) | 8.2 (5.5-12.0) | 25.9 (13.5-NE) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | ||

| Median OS (95% CI) | 8.8 (6.7-10.2) | 11.6 (8.9-15.5)* |

| Estimated 18-mo survival probability in patients with CR/CRh | 50% | 78% |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IQR, interquartile range; PS, performance status.

In the 153-patient safety population (which included the 147-patient efficacy-evaluable population plus 6 patients with a lack of a centrally confirmed IDH1 mutation).

Adapted from Venugopal and Watts.41

OLU (FT-2102), an oral, selective IDH1mut inhibitor, was approved in 2022 for R/R IDH1mut AML. The phase 1 study evaluated OLU monotherapy and a combination with AZA (OLU-AZA) in both treatment-naive and R/R IDH1mut AML/MDS, and a signal of efficacy was observed in all cohorts.12 In the pivotal phase 2 cohort in R/R IDH1mut AML, 153 IDH1 inhibitor-naive patients received OLU at 150 mg twice daily.12 In this cohort the CR plus CRh rate was 35% (95% CI, 27.0-43.0), with a 32% CR rate. The median duration of CR plus CRh was 25.9 months (95% CI, 13.5-NE), and median OS was 11.6 months (95% CI, 8.9-15.5). AEs of special interest (grade ≥3) included hepatic enzyme elevation (15%) and IDH differentiation syndrome (9%). In updated results from all phase 2 cohorts, 17 patients (15 receiving OLU monotherapy and 2 in combination with AZA) had prior exposure to VEN, of which 7 achieved a CR, CRh, or CRi (41%), and the median duration of CR/CRh (5 patients) was 18.5 plus months at the data cutoff date.14,15 OLU-AZA was evaluated in multiple subcohorts on the phase 2 study and demonstrated durable clinical activity in treatment-naive AML and R/R patients without prior exposure to an HMA or IDH1 inhibitor.16 The activity of OLU after IVO treatment failure is unknown, although preclinical studies suggest it may have activity in second-site mutations.17

In R/R IDH1mut AML, the management decision is dictated by the first-line treatment. Given available data, we would propose IVO or OLU monotherapy or an HMA-VEN regimen (prospective data are with decitabine) for patients with prior exposure to IC and consider OLU monotherapy for patients with prior exposure to AZA-VEN, given the limited prospective data.18,19

Clinical scenario: older adult with IDH2-mutant AML, treatment-naive and relapsed settings

For treatment-naive patients with IDH2mut AML ineligible for IC, AZA-VEN is standard therapy. Enasidenib (ENA), an oral, selective IDH2mut inhibitor, is approved in the R/R setting (Table 3.20 In the pooled analysis of AZA-VEN studies,11 68 patients with ND AML (n = 498, 14%) harbored IDH2mut. Among those who received AZA-VEN (n = 50), the CRc rate was 86% with a 56% CR rate. Most patients achieved their response (CR or CRi) in the first cycle, and the median DoR (95% CI, 16.7-NE) and median OS (95% CI, 17.6-NE) were not reached. The AG221-AML-005 trial evaluated ENA-AZA against AZA monotherapy in ND, IC-ineligible IDH2mut AML (N = 107). Among the efficacy-evaluable population (n = 101), rates of CR plus CRh (57% vs 18%; P = .0002), CR (54% vs 12%; P < .0001), and median DoR (24.1 vs 9.9 months) were significantly higher in the ENA-AZA arm compared to AZA monotherapy. Nevertheless, there was no difference in median OS (15.9 vs 11.1 months; P = .11) between treatment arms, perhaps influenced by a lack of placebo control and the subsequent use of ENA in patients on the AZA monotherapy arm. Serious AEs included febrile neutropenia (13%) and differentiation syndrome (10%).21 In a single institutional study of ENA-AZA in patients with IDH2mut AML, outcomes were better in those with early vs late relapse, and a small group of R/R patients with prior exposure to ENA or AZA showed a signal of activity with ENA-AZA-VEN triplet therapy.22

Comparison of baseline demographics and efficacy outcomes in patients with IDH2mut AML treated on the VIALE-A (pooled analysis), AG221-AML-005, and ENA (registrational trial)

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | AZA with VEN N = 50 . | ENA with AZA N = 68 . | ENA N = 109 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 76 (64-90) | 75 (70-79) | 67 (19-100) |

| Trial design and setting | Phase 3, ND | Phase 1b/2, ND | Phase 1/2, relapsed/refractory |

| Response outcomes | |||

| Composite CR (CRc*) rate | 86% | 57% | 26.8% |

| CR rate | 56% | 54% | 20.2% |

| Duration of response (mo) | |||

| Median time to CRc (range or IQR) | 1.1 (0.7-8.8) | 4.6 (2.3-6.7) | 3.7 (0.7-11.2) |

| Median duration of CRc (95% CI) | NE (16.7-NE) | NE (10.2-NE) | 8.8 (0.7-11.2) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | |||

| Median OS (95% CI) | NE (17.6-NE) | 22.0 (14.6-NE) | 9.3 (8.2-10.9) |

| Estimated 12-mo survival probability (95% CI) | 75.6% (61-85.3) | 72% (60-82) | 39% |

| Efficacy-evaluable population . | AZA with VEN N = 50 . | ENA with AZA N = 68 . | ENA N = 109 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range or IQR) | 76 (64-90) | 75 (70-79) | 67 (19-100) |

| Trial design and setting | Phase 3, ND | Phase 1b/2, ND | Phase 1/2, relapsed/refractory |

| Response outcomes | |||

| Composite CR (CRc*) rate | 86% | 57% | 26.8% |

| CR rate | 56% | 54% | 20.2% |

| Duration of response (mo) | |||

| Median time to CRc (range or IQR) | 1.1 (0.7-8.8) | 4.6 (2.3-6.7) | 3.7 (0.7-11.2) |

| Median duration of CRc (95% CI) | NE (16.7-NE) | NE (10.2-NE) | 8.8 (0.7-11.2) |

| Survival outcomes (mo or percentage) | |||

| Median OS (95% CI) | NE (17.6-NE) | 22.0 (14.6-NE) | 9.3 (8.2-10.9) |

| Estimated 12-mo survival probability (95% CI) | 75.6% (61-85.3) | 72% (60-82) | 39% |

IQR, interquartile range.

Here defined as CR plus CRi in VIALE-A (pooled analysis) and enasidenib and CR plus CRh in AG221-AML-005. CR plus CRi in AG221-AML-005 was 63%.

IC-ineligible adults with treatment-naive IDH2mut AML are highly sensitive to AZA-VEN, and we would strongly recommend this approach as first-line therapy. In the relapsed setting post AZA-VEN, ENA monotherapy is the standard of care, and in R/R patients without prior exposure to HMA or VEN, ENA or an HMA-VEN regimen may be considered.

Future directions in IDH1/2mut AML: triplet (AZA-VEN-IDH1/2 inhibitor) vs. sequencing with IDH1/2 inhibitors

In a phase 1b study evaluating the safety and efficacy of IVO-VEN plus or minus AZA (IVO-VEN-AZA) in IDH1mut myeloid malignancies (n = 31),23 the AE profile was similar to that of IVO or AZA monotherapy, and the maximum tolerated dose was not reached. Of note, VEN was given for 14 days starting with cycle 1 and was studied at both 400 mg and 800 mg daily given potential pharmacokinetic interactions with IVO. Clinical activity was observed with IVO-VEN and IVO-VEN-AZA (CRc, 83% and 90%, respectively) with no difference in survival between IVO-VEN and IVO-VEN-AZA (42.1 months vs not reached [NR]; P = .13), and enrollment continues on the IVO-VEN-AZA cohort.23 In another nonrandomized study evaluating total oral therapy with cedazuridine-decitabine (days 1-5), VEN (days 1-14), and IVO or ENA, robust treatment response was observed in treatment-naive patients. In the R/R setting, responses were more pronounced in those without prior VEN exposure.24 Triplet regimens may increase the likelihood of receiving a curative-intent hematopoietic stem cell transplant in a selected subset of older adults. The I-DATA study (NCT05401097) comparing the order of treatment with IVO-ENA monotherapy and AZA-VEN in treatment-naive, IC-ineligible patients should offer some clarity on the sequencing of these agents. Ultimately, randomized studies of AZA-VEN-IDH inhibitor vs AZA-VEN (possibly followed by an IDH inhibitor) are needed, and differences in sensitivity to AZA-VEN by the IDHmut subtype and the unique clinical profiles of available IDH inhibitors should be considered. Switch maintenance studies (AZA-VEN followed by IDH1 inhibitor-AZA once remission is achieved) are also under consideration.

Clinical scenario: older adult with relapsed NPM1mut AML

Mr. X, now 81 years of age, presents with prolonged pancytopenia prior to starting his 14th cycle of IVO-AZA. The bone marrow biopsy evaluation confirmed relapsed AML, and molecular studies identified NPM1 (VAF, 50%), DNMT3A (VAF-40%), and BCOR (VAF, 25%) mutations. What is the appropriate treatment regimen for this patient?

Approximately 10% to 40% of patients with NPM1mut AML relapse, depending on various factors, and a single-center report suggests that adding VEN to either high- or low-intensity salvage regimens may improve outcomes in these patients.25 In addition, preclinical studies have shown that deregulation of the HOXA9/MEIS1 axis drives leukemogenesis in NPM1mut AML and that menin-MLL inhibition abrogates this phenotype.26 In a phase 1 study evaluating patients with R/R AML including NPM1mut, revumenib (SNDX-5613), a selective oral menin inhibitor, demonstrated tolerability and clinical activity (CRc, 36% in NPM1mut AML) in a heavily pretreated population. AEs of special interest included QTc prolongation (53%) and differentiation syndrome (16%).27 In the absence of a clinical trial evaluating targeted therapies in NPM1mut AML, we would recommend a VEN-based regimen for this patient with relapsed NPM1mut AML after prior treatment with IVO-AZA.

Clinical scenario: older adult with FLT3mut AML

Mr. Z, a 78-year-old man, presents with a WBC of 40 × 109/L, a hemoglobin level of 7.4 g/dL, and a platelet count of 70 × 109/L. Bone marrow biopsy confirms AML with 67% myeloblasts and a normal karyotype, and the molecular studies identify NPM1 (VAF, 40%), FLT3-ITD (allele ratio, 0.83), and IDH2 (VAF, 22%) mutations. What is the appropriate frontline treatment option for this patient?

Currently, there are no approved targeted options for treatment-naive patients with FLT3mut AML who are IC ineligible. In the pooled analysis of AZA-VEN studies,28 64 patients with ND AML (n = 498, 13%) harbored FLT3mut. Among those who received AZA-VEN (n = 42), 30 had FLT3-ITD and 12, FLT3-TKD mutations. The CRc rates in patients with FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD were 63.3% and 77%, respectively. Among these patients, median OS was longer in those with FLT3-TKD (19.2 months; 95% CI, 1.8-NE) compared to FLT3-ITD (9.9 months; 95% CI, 5.3-17.6).28 In a proof-of-concept study allowing the addition of an FLT3i to a decitabine-VEN backbone (n = 25), CRc rates were 92% (polymerase chain reaction/next-generation sequencing negativity, 91%) and 62% (polymerase chain reaction/next-generation sequencing negativity, 100%) in ND (IC-ineligible) and R/R FLT3mut AML (including prior FLT3i exposed), respectively.29 Triplet therapy combining the FLT3i gilteritinib (GILT) with AZA-VEN, with modified dosing for myelosuppression, is also being evaluated in this population,30 and a multicenter study is planned (VICEROY).

In the R/R setting, the VEN-GILT doublet has shown promising clinical activity in a phase 1b study (n = 61 patients with R/R FLT3mut AML). The primary end point was a modified CRc rate (mCRc, CR minus CRi plus CRp plus morphologic leukemia-free state), and prior VEN or FLT3i (other than GILT) was allowed (64% had prior FLT3i exposure). VEN at 400 mg plus GILT at 120 mg/day was chosen as the recommended phase 2 dose based on clinical activity (75% mCRc rate) and tolerability. Cytopenias of grade 3 or above were observed in 80% of patients, and approximately 50% required dose interruptions secondary to VEN or GILT-related AEs. While VEN-GILT demonstrated activity even in patients with prior FLT3i exposure (67% mCRc rate), myelosuppression can be prolonged, and dose modifications for tolerability were common, highlighting the need for robust clinical trials to further examine the safety and efficacy of VEN-based combinations.31

In IC-ineligible patients with FLT3mutAML, we recommend AZA-VEN in the frontline setting and GILT monotherapy in the R/R setting, outside of a clinical trial.

Clinical scenario: older adult with TP53mut AML

Ms. Y, a 76-year-old woman with a previous history of large-cell lymphoma treated with chemotherapy 5 years ago, presents with a WBC of 2.5 × 109/L, a hemoglobin level of 7.9 g/dL, and a platelet count of 45 × 109/L. Bone marrow biopsy confirms AML with 67% myeloblasts and a complex karyotype with 17p deletion, and molecular studies identified a TP53 R282W (VAF, 73%) mutation. What is the appropriate frontline treatment option for this patient?

Improving the short-lived remissions and inferior survival in TP53mut AML remains the Sisyphean endeavor of the leukemia research community. In particular, TP53 multihit status is notoriously refractory to treatment.32 Retrospective and prospective studies have shown that adding VEN to HMA or chemotherapy does not improve survival in TP53mut AML.33,34 In the pooled analysis of AZA-VEN studies, there was no difference in OS between those who received AZA-VEN and AZA (5.2 vs 4.9 months).35 Magrolimab (MAGRO) is a first-in-class humanized anti-CD47 antibody that blocks CD47 binding to signal-regulatory protein-α and promotes phagocytosis of leukemic cells.36 MAGRO-AZA has been evaluated in patients with untreated higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 95),37 of which 26.3% harbored a TP53 mutation (n = 25). Anemia was the most common MAGRO-related AE (37.9%), which resolved with subsequent cycles. Among those with TP53mut, 10 (40.0%) achieved CR. At the median follow-up of 12.5 months, DoR was 7.6 months (95% CI, 3.1-13.4), and median OS was 16.3 months (95% CI, 10.8-NR) in TP53mut patients.37 Given this encouraging activity, the phase 3 ENHANCE-2 study is evaluating MAGRO-AZA vs AZA-VEN or IC in treatment-naive patients with TP53mut AML (NCT04778397). Triplet therapy with MAGRO-AZA-VEN is underway and has demonstrated preliminary activity in frontline and R/R AML, TP53mut and wild type,38 and the phase 3 ENHANCE-3 study is evaluating triplet MAGRO-AZA-VEN vs AZA-VEN in all-comers with ND, IC-ineligible AML (NCT05079230). Immunotherapy approaches such as anti-CD3/CD123 bispecific antibodies, with or without an AZA-VEN backbone, may also have a role,39,40 and other therapies exploiting CD47/signal-regulatory protein-α are under investigation.

Conclusions

Increased biological understanding of AML has translated into an expansion of the AML treatment landscape with rational combinations incorporating molecularly targeted therapies. In the era of precision medicine, tolerable regimens combining targeted agents with an HMA-VEN backbone may improve outcomes in IC-ineligible patients across various molecular subsets (IDH1/2, NPM1, FLT3, TP53). Ongoing and future clinical trial evaluations should guide us in the choice of treatment regimens, answering critical questions about topics such as the use of frontline triplet combinations, compared with the sequencing of targeted therapies. Triplet regimens may be associated with increased toxicity, and equipoise is needed to optimize treatment approaches and delineate survival advantages in multicenter trials. Despite unresolved questions, having these tailored treatment options available for our patients represents a major advance compared to less than a decade ago.

Acknowledgments

For all our patients, who teach us so much every day.

Visual abstract created with biorender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Sangeetha Venugopal: no competing financial interests to declare.

Justin Watts: advisory board: Rigel, Forma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda; consultancy: Rigel, Forma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda; research funding: Takeda, Immune Systems Key; data monitoring board: Rafael, Reven Pharma.

Off-label drug use

Sangeetha Venugopal: Nothing to disclose.

Justin Watts: Nothing to disclose.