Abstract

Von Willebrand disease (VWD), the most common inherited bleeding disorder (IBD), disproportionately affects females, given the hemostatic challenges they may encounter throughout their lifetimes. Despite this, research about VWD remains grossly underrepresented, particularly compared to hemophilia, which is historically diagnosed in males. Structural sexism, stigmatization of menstrual bleeding, delayed diagnosis, and a lack of timely access to care result in an increased frequency of bleeding events, iron deficiency, iron deficiency anemia, and a decreased quality of life. However, we are only beginning to recognize and acknowledge the magnitude of the burden of this disease. With an increasing number of studies documenting the experiences of women with IBDs and recent international guidelines suggesting changes to optimal management, a paradigm shift in recognition and treatment is taking place. Here, we present a fictional patient case to illustrate one woman's history of bleeding. We review the evidence describing the impact of VWD on quality of life, normalization of vaginal bleeding, diagnostic delays, and the importance of access to multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, we discuss considerations around reproductive decision-making and the intergenerational nature of bleeding, which often renders patients as caregivers. Through incorporating the patient perspective, we argue for an equitable and compassionate path to overcome decades of silence, misrecognition, and dismissal. This path moves toward destigmatization, open dialogue, and timely access to specialized care.

Learning Objectives

Review the negative impact of von Willebrand disease on health-related quality of life

Describe the patient and health care provider struggle to identify abnormal vaginal bleeding

Discuss how the stigmatization of vaginal bleeding and differential access to care contribute to misdiagnosis and diagnostic delay

Emphasize patient empowerment through multidisciplinary care, advocacy, and education

Introduction

Despite its autosomal inheritance pattern, females are more likely to be diagnosed with von Willebrand disease (VWD) than males due to the regular physiological opportunities to bleed during their reproductive years. The health disparities among women compared to men with inherited bleeding disorders (IBDs) are abundantly clear; therefore, understanding and highlighting women's experiences with VWD is of particular importance. Here, we explore evidence-based themes that have emerged in recent years among women with bleeding disorders, including VWD, through a patient-focused lens. Throughout this article we predominantly use the term “women” to highlight the experiences of and care gaps for women with bleeding disorders and the term “females” to address discrepancies rooted in biologic processes. We acknowledge that these terms are exclusive, and we ask the reader to please recognize that these experiences may also apply to all people with the anatomy that allows for menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth, including girls, transgender men, intersex people, and gender nonbinary individuals. Furthermore, the author team of this article includes a woman with VWD to represent the patient voice.

CLINICAL CASE

A 12-year-old girl experienced lifelong easy bruising and frequent epistaxis. Despite this, she actively participated at her school and swam on a swim team prior to menarche. Her menstrual periods began at age 13, occurred monthly, and lasted 8 days. On the 2 heaviest days, she changed her pad hourly to avoid flooding. She had multiple “embarrassing” episodes of bleeding at school and sometimes stayed home from school during her period. At the age of 14, she quit the swim team due to the anxiety provoked by her heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Her mother and older sister sympathized since they had similar experiences. She became increasingly fatigued and had difficulty concentrating at school, which prompted a visit with her family physician. She was diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and was started on an oral iron supplement and oral contraceptive pill.

The impact of VWD on health-related quality of life, hobbies, education, and work

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is a metric that quantifies a patient's physical, emotional, mental, social, and behavioral health.1 HRQOL scores are lower in those with VWD than in the general population,2,3 and those with severe bleeding, children, and women appear to be disproportionately negatively affected.3 In addition to having lower HRQOL scores, children with VWD also experience higher rates of anxiety and depression relative to unaffected children.4

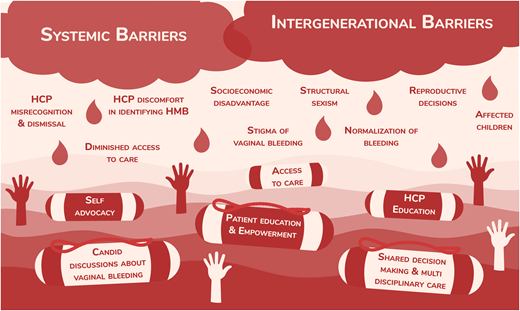

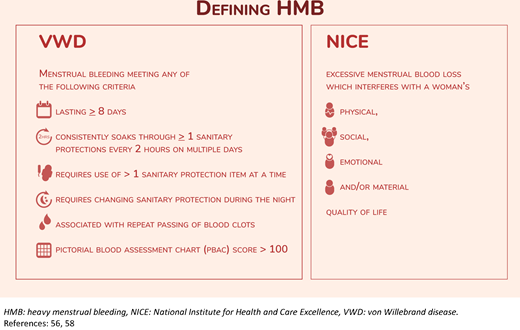

Teenage girls with IBDs have markedly lower HRQOL scores, particularly in the domains of school functioning and psychosocial health.5 This is likely due to HMB (Figures 1 and 2) since VWD's impact on HRQOL is most pronounced among those who experience HMB.6,7 Still, tools to quantify this are imperfect and likely underestimate the true impact of HMB on HRQOL. Interviewed women with abnormal vaginal bleeding confirmed that current HRQOL questionnaires inadequately captured the depth of their experiences.8 However, despite the limitations of existing tools, HMB has been associated with higher rates of anxiety and reduced HRQOL.9,10 Other factors with a negative impact on HRQOL in women with HMB include higher rates of dysmenorrhea,7,11,12 ID, and anemia.3,13 To contextualize the HRQOL of a woman with VWD and menorrhagia, it parallels that of an HIV-positive man with severe hemophilia.7 There is evidence in the adolescent population that treating HMB with hemostatic or hormonal therapy can mitigate the negative effect of VWD on HRQOL measures,14 yet these treatments may be underutilized, as impaired QOL persists despite treatment.12

Factors contributing to reduced HRQOL in those with heavy menstrual bleeding.

Modern definitions of heavy menstrual bleeding. NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Modern definitions of heavy menstrual bleeding. NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

The perceived and measured impact of HMB on a patient's overall life activities, including work, school, and hobbies, is significant.12,15–18 Women with VWD and HMB have reduced participation in sports and physical activity and are less likely to enroll in postsecondary education than men with VWD.6,19 These missed opportunities to participate due to HMB result in feelings of “otherness” and isolation.18 Further, women with an IBD commonly describe a loss of accomplishment at work and are more likely to report losing time from school or work due to HMB.10,11 The losses in productivity are likely due to physical limitations from pain and IDA, as well as the anxiety and stigma surrounding vaginal bleeding events.15,18 Moreover, diminished education and employment opportunities have profound and enduring socioeconomic consequences for women with VWD,17 which further compounds and perpetuates health inequity. There is an irrefutable negative impact of VWD on HRQOL that is exacerbated by HMB.

Normalization and desensitization to heavy vaginal bleeding

For many young people, parents and caregivers play a key role in their understanding and conceptualization of menstruation.15,20 Over 70% of females with VWD experience HMB11,21,22 ; furthermore, for 1 in 5 adolescents with an IBD this is their only symptom.14 These are likely gross underestimates; many experts believe that essentially all females with VWD experience HMB or other excessive vaginal bleeding at some point during their lives. In families affected by VWD, heavy vaginal bleeding (including HMB and excessive postpartum bleeding) is common.11,21–23 Individuals often gauge the normalcy of their vaginal blood loss by referencing family and personal experiences.15,24 When those referenced also have abnormal bleeding, heavy vaginal bleeding is normalized, and generations become desensitized.15,24 This is supported by a study of females with VWD in which 71.4% of those who reported “normal menstrual bleeding” had clinical measurements consistent with HMB.12 Furthermore, the stigma surrounding menstruation obstructs conversations about vaginal bleeding with nonrelatives.15 For these reasons, many wait years prior to seeking medical assessment for HMB and 40% never do.25 These challenges highlight the need to combat stigmatization to allow for candid conversations about vaginal blood loss.

CLINICAL CASE (Continued)

At age 27 this woman became pregnant, and her nosebleeds increased in frequency to weekly. She mentioned this to her obstetrician at multiple visits and was advised to use an air humidifier. Considering her bothersome epistaxis, she searched the internet and came across letstalkperiod.ca and a self-administered Bleeding Assessment Tool. Her results were flagged as abnormal, but she ignored these, not believing her bleeding was “abnormal enough” to represent a bleeding disorder. At 28 weeks' gestation, she presented to the emergency department for a nosebleed lasting 6 hours. Following tranexamic acid and cauterization, the bleeding stopped, and she was referred to a hematologist.

At 32 weeks' gestation, she was assessed and diagnosed with type 2A VWD, which was confirmed with genetic testing. She was followed by a hematologist connected to a hemophilia treatment center (HTC) throughout her pregnancy. A delivery plan was developed in conjunction with her obstetrician, a pediatric hematologist, and an anesthesiologist. She received prophylactic von Willebrand factor (VWF) replacement and tranexamic acid prior to epidural catheter placement and underwent an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Her baby was evaluated by a pediatrician at delivery and safely provided with subcutaneous vitamin K. She was discharged home with an additional 4 days of VWF replacement and oral tranexamic acid until her lochial losses subsided. In contrast, her sister, who lived in rural Oklahoma, gave birth 7 months prior and experienced a severe postpartum hemorrhage requiring transfusion.

Misdiagnoses and diagnostic delay

While VWD remains the most prevalent IBD,26 diagnostic delay and misdiagnoses make timely identification and management challenging. Historically, interviews conducted in the US demonstrated that the average time from first patient symptom to clinician recognition was 16 years.27 Two key contributing factors were identified: underrecognition of HMB as being associated with VWD and a lack of appropriate access to coagulation testing.27

Unfortunately, recent work revealed persistent challenges with diagnostic delay and misrecognition, and this seems to be sex-specific; while females received more frequent referrals for bleeding, diagnostic delay was on average 6 years longer for females than males.28 This was in spite of a similar age at first bleed, as well as a similar frequency of abnormal bleeding symptoms and bleeding episodes requiring treatment.28 In 2019 the median age of diagnosis among females with congenital bleeding disorders was 16.13 Risk factors for delayed diagnosis included an absence of known family history and a lack of recognition of abnormal bleeding.28

Qualitative work has expanded upon these observations, providing insight into why many women may not receive a diagnosis for years after initial symptom presentation. A study interviewing 15 women with IBDs described the challenges differentiating normal from abnormal bleeding symptoms and the lack of timely specialist referrals.15 Participants additionally discussed receiving incorrect diagnoses for multiple years.

Barriers to diagnosing females with HMB due to VWD include health care provider (HCP) difficulty identifying abnormal menstrual bleeding and a failure to screen for VWD; for example, less than 20% of adolescents with HMB are screened for VWD.29,30 In addition, recognizing abnormal menstrual bleeding is particularly challenging in adolescents due to the high frequency of abnormal or anovulatory uterine bleeding at menarche.31 Therefore, even if patients identify abnormal bleeding and present for medical attention, they frequently still experience dismissal or serial misrecognition of their concerns and resultant delays in diagnosis and treatment.32-34 In addition to expediting access to treatment, a formal diagnosis has critical psychological benefits for affected individuals, such as facilitating a sense of empowerment and identity formation.18

Need for self-education and advocacy

A lack of HCP awareness of IBDs and HCP symptom dismissal are significant barriers to patient care, while patient self- education and advocacy are protective.32 The publicly available arsenal of self-advocacy tools has steadily been increasing to support patient needs, allowing patients to assert agency over their health. These initiatives include, but are not limited to, the Hemophilia Federation of America's “Bleeders' Bill of Rights,” websites such as letstalkperiod.ca, which includes the Bleeding Assessment Tool, and nonprofit organizations that operate on both local and national levels.35–37 As self-education directly results in a patient's ability to self-advocate, resources must be as widely accessible as possible.32 These may include being available in both print and online formats in multiple languages and using various methods of communication—for example, text accompanied by visuals. While it is important to acknowledge the need for patient self-education and self-advocacy, it is equally important to highlight the disparity in this need among women with bleeding disorders compared to men. It is unfortunate to shoulder patients with any medical disorder with excessive responsibility, and it is inequitable and unjust to burden one demographic more than another.

Access to multidisciplinary care

Multiple barriers to care exist, including geographic barriers, a lack of specialist access, a lack of understanding of normal vs abnormal bleeding, and a lack of access to timely treatment.32 Simultaneously, the importance of multidisciplinary clinics has been increasingly recognized. Recent international guidelines highlight the importance of multidisciplinary teams, particularly teams involving both hematologists and gynecologists, to manage HMB.38 Furthermore, it is a well-described fact that patients at HTCs are more likely to receive treatment than their counterparts at other centers.13 However, individuals with VWD may not be aware of the existence of such HTCs, which hinders their ability to request a referral and receive timely multidisciplinary care. Additionally, a patient's experience with symptom dismissal may lead to tension with the health care system, disincentivizing further engagement with HCPs and thus hindering comprehensive care. Acknowledging a patient's personal history with health care can give reassurance, provide validation, and foster trust, which cultivates a trauma-informed and patient-centered approach to care.

The pregnancy and postpartum periods represent unique times during which multidisciplinary care is especially warranted.24,39,40 Integrated care has evolved beyond the HTC to include specialized multidisciplinary clinics for females with IBDs, acknowledging that this population presents areas of uncertainty and the opportunity for collaborative peripartum care.41–43 Broadly, we advocate for shared care between nurses, hematologists (both adult and pediatric), obstetricians, and anesthesiologists throughout the management of pregnancy, labor, and delivery.41,43 From a patient's perspective, this multidisciplinary model can be successful, with patients describing a sense of empowerment and control when provided with a clear care plan.24

While tremendous progress has been observed in multidisciplinary care provision, geographic status as a potential barrier to care should not be ignored.32 Telehealth and virtual health initiatives may provide creative solutions to this problem, ensuring that patients receive comprehensive, accessible care regardless of geographic residency.32 Finally, multidisciplinary team members must also include HCPs closer to home, as delivery within the community where the patient resides is often desired and should be provided as an option when safe.

CLINICAL CASE (Continued)

At birth, the patient's son was tested and diagnosed with type 2A VWD. He received care from a pediatric HTC. While learning to walk, he fell and developed a large hematoma on his forehead that required VWF replacement therapy. Following this event, his mother joined an online support group for parents of children with bleeding disorders. One year postpartum, she and her partner considered a second pregnancy.

Reproductive decision-making

Being diagnosed with an IBD complicates decisions regarding conception. Most types of VWD are inherited in an autosomal dominant or codominant fashion,44 giving offspring a 50% chance of being affected. Preconception counseling is critical in empowering patients to make informed decisions.45,46 As expected, feelings surrounding the potential inheritance of VWD by their children vary among women: some approach the situation pragmatically (eg, “I am worried but I will teach them to manage it as I have done”), while others describe feelings of guilt.16 Reproductive decisions among patients with heritable disorders are nuanced and personal. One in 4 women with an IBD state that their diagnosis had a severe impact on their decision to have children.13 Unfortunately, many women with VWD feel uncomfortable discussing their reproductive health concerns with their HCPs, making it imperative that HCPs create a safe space for these concerns to be voiced.47 Still, the reproductive options of some females with VWD are prematurely restricted since hysterectomy is more common in this population and occurs at a younger age.48,49

The patient as a caregiver

Bleeding does not occur in isolation but rather in the context of an intergenerational history of bleeding.15 This becomes increasingly complex when an individual with VWD becomes a parent to an affected child. Our understanding of the experience of parenthood among affected caregivers stems largely from the hemophilia literature. In this population, caregivers experience financial burden, emotional stress, personal sacrifice, and change or loss of employment.50–53 More than half of parents of children with an IBD describe isolation, grief, frustration, and anger.51 Sadness and guilt surrounding a child's IBD are also expressed, particularly at diagnosis, when many mothers of affected children feel a “sense of being accused.”45,53 Intergenerational feelings of guilt and shame may also be passed down.

Empowerment through community affiliation

Whether virtually or in person, many people living with IBDs benefit from the support of other affected individuals.16 Adolescent girls in particular appear to find value in sharing their lived experiences, and many express a desire to have a network of girls and women whom they can ask “real-life” questions.16 This sense of community offsets the isolation and stigmatization that can accompany a bleeding disorder diagnosis and instead provides empowerment and a sense of acceptance.15

Conclusion

We have presented data documenting the multifaceted negative impact that VWD has on HRQOL. The negative effect is exacerbated by heavy vaginal bleeding, which is inappropriately normalized by patients and HCPs alike due to deep-rooted stigmatization and structural sexism. These challenges have led to persistent guilt, shame, dismissal, misrecognition, diagnostic delay, and lack of treatment. Solutions include patient and HCP education, advocacy initiatives, and access to specialized multidisciplinary care with shared decision-making. The onus should not remain on patients alone, as systemic barriers require systemic solutions. Furthermore, as Weyand and James astutely highlight, when compared to hemophilia, which is most commonly diagnosed in males, VWD is severely underrepresented in bleeding disorder research despite being over 10 times more prevalent.54 The stigmatization of vaginal blood loss likely contributes to the paucity of evidence to guide HMB management in those with VWD or other IBDs. For example, on average, a male with severe hemophilia A experiences fewer than 5 bleeds per year with prophylaxis,17,55 while a female with VWD has monthly hemostatic challenges that contribute to the normalization and acceptance of abnormal bleeding.15,24,47 It is a significant step forward that recent international VWD guidelines present a recommendation on VWF prophylaxis for individuals with HMB.38 Still, in clinical practice the number of bleeds required prior to considering the initiation of prophylaxis further highlights the disparity between the approach to the care of a male with hemophilia vs a patient with VWD. A patient with VWD must “earn” prophylaxis in a way that the patient with hemophilia does not. Despite the high prevalence of VWD and the near universality of HMB, the role of VWF replacement for the prophylaxis of HMB is as yet undetermined in VWD. We are grateful for the efforts of the American Society of Hematology, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, National Hemophilia Foundation, and World Federation of Hemophilia to develop a forward-thinking framework of 2021 guidelines to care for patients with VWD and identify key opportunities to improve the care of females with VWD, including optimal management of HMB, neuraxial anesthesia at delivery, and prevention of postpartum bleeding.38 Furthermore, we are grateful for the move away from frankly unfeasible vaginal bleeding assessments and the shift toward relatable, modern, and qualitative assessments that consider contemporary menstrual products and emphasize the impact of excessive bleeding on QOL (Figure 2).56–58 It is time to collectively address the knowledge and care gaps for females with VWD, call out structural sexism in medicine, and conduct timely and high-quality research in this wide-open field.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Heather VanderMeulen: no competing financial interests to declare.

Sumedha Arya: no competing financial interests to declare.

Sarah Nersesian: no competing financial interests to declare.

Natalie Philbert: no competing financial interests to declare.

Michelle Sholzberg: research funding: Octapharma, Pfizer; honoraria: Octapharma, Pfizer, Takeda.

Off-label drug use

Heather VanderMeulen: nothing to disclose.

Sumedha Arya: nothing to disclose.

Sarah Nersesian: nothing to disclose.

Natalie Philbert: nothing to disclose.

Michelle Sholzberg: nothing to disclose.