Abstract

Heterogeneous red blood cell (RBC) membrane disorders and hydration defects often present with the common clinical findings of hemolytic anemia, but they may require substantially different management, based on their pathophysiology. An accurate and timely diagnosis is essential to avoid inappropriate interventions and prevent complications. Advances in genetic testing availability within the last decade, combined with extensive foundational knowledge on RBC membrane structure and function, now facilitate the correct diagnosis in patients with a variety of hereditary hemolytic anemias (HHAs). Studies in patient cohorts with well-defined genetic diagnoses have revealed complications such as iron overload in hereditary xerocytosis, which is amenable to monitoring, prevention, and treatment, and demonstrated that splenectomy is not always an effective or safe treatment for any patient with HHA. However, a multitude of variants of unknown clinical significance have been discovered by genetic evaluation, requiring interpretation by thorough phenotypic assessment in clinical and/or research laboratories. Here we discuss genotype-phenotype correlations and corresponding clinical management in patients with RBC membranopathies and propose an algorithm for the laboratory workup of patients presenting with symptoms and signs of hemolytic anemia, with a clinical case that exemplifies such a workup.

Learning Objectives

Discuss comprehensive evaluation for RBC membrane disorders, including phenotypic and genetic testing

Review clinical management considerations tailored to the genetic diagnosis and pathophysiology of RBC membrane disorders

Elaborate on patient cases of RBC membrane skeleton disorders and hydration defects

CLINICAL CASE

A European American boy presented with nonimmune hemolyticanemia and hyperbilirubinemia as a neonate, requiring red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and phototherapy. He continued to require frequent transfusions every 4 to 8 weeks. There was no family history of hemolytic anemia. His mother had some spherocytes on her blood smear, but she was asymptomatic with no evidence of hemolysis. Since the patient had been regularly transfused since birth, an RBC phenotypic evaluation was not feasible to provide a diagnosis. Therefore, genetic evaluation on a next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel of genes associated with hereditary hemolytic anemia (HHA)was performed that showed a nonsense SPTA1 mutation (c.4295del, p.Leu1432*)and the low-expression SPTA1 polymorphism c.4339-99C>T (also known as αLEPRA or low expression PRAgue). αLEPRA, a deep intronic variant that affects splicing, causes a significant decrease in the amount of normal α-spectrin produced from the affected allele. Compound heterozygosity of αLEPRA with a null SPTA1 mutation in trans is the most common cause of autosomal recessive (AR) hereditary spherocytosis (HS) due to α- spectrin deficiency.1-3 In addition, a variant of unknown clinical significance (VUCS) was identified in PIEZO1: c.6205G>A (p.Val2069Met), which, if pathogenic, could cause a component of xerocytosis in this patient. Splenectomy in hereditary xerocytosis (HX) is associated with life-threatening thrombophilia; therefore, it was important to explore the contribution of this PIEZO1 VUCS to the patient's disease.

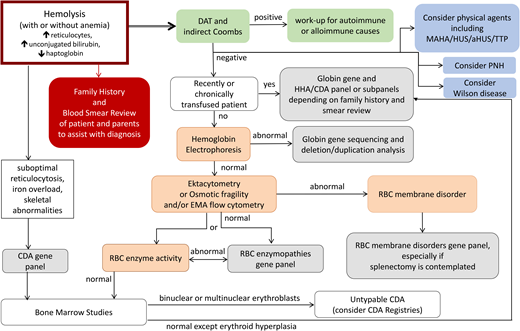

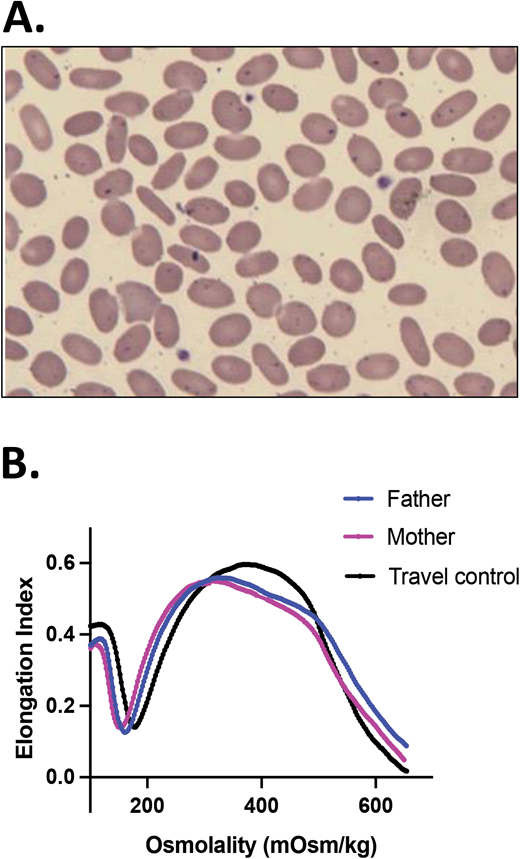

Parental studies were performed and confirmed that the SPTA1 mutations were positioned in trans and were therefore pathogenic, causing HS. The father carried αLEPRA and the PIEZO1 p.Val2069Met variant while the mother carried the nonsense SPTA1 mutation p.Leu1432*. The patient had osmotic gradient ektacytometry performed 8 weeks after a transfusion that showed decreased EImax (maximum elongation index; ie, the maximum deformability of the RBCs), compatible with HS but not typical since Omin (ie, the hypotonic osmolality in which the elongation index is minimal) and Ohyp (ie, the osmolality value at which the cells' average maximum diameter is half of EImax) were normal because normal donor RBCs were still present in his blood (Figure 1A).4 Both parents had a normal hemoglobin (Hgb) and reticulocyte count as well as normal ektacytometry. Each normal SPTA1 gene produces α-spectrin well in excess; therefore, it was not surprising that neither parent had HS. In addition, the ektacytometry curve of the father's blood sample showed no evidence of HX despite carrying the PIEZO1 VUCS. RBC cation content was evaluated for both parents and was within normal range, offering additional reassurance that the PIEZO1 p.Val2069Met variant was benign.

HS.(A)Ektacytometry of blood samples from the patient before and after splenectomy and from his parents. The patient had AR HS due to compound heterozygosity of SPTA1 c.4295del (p.L1432*), shared with the mom, and SPTA1 c.4339-99C>T, shared with the dad. The dad and the proband were also found to carry the PIEZO1 VUCS c.6205G>A (p.Val2069Met). The parents had a normal ektacytometry with no evidence of xerocytosis for the father, offering reassurance that the PIEZO1 VUCS is benign, while the patient after splenectomy had a typical HS curve. Before splenectomy, the patient was chronically transfused. Ektacytometry at that time was performed at a nadir before the next transfusion and 2 months after a previous one. Transfused RBCs have obviously modified the curve, giving a falsely normal Omin (ie, the hypotonic osmolality where the elongation index is minimal). The value of Omin provides information on the initial surface-to-volume ratio of the cell sample. A shift to the right reflects a decrease in the surface area/volume ratio and corresponds to increased osmotic fragility. (B) Blood smear of the patient about 18 months post partial splenectomy before starting to require transfusions again, demonstrating significant anisopoikilocytosis and polychromasia as well as many spherocytes, typical for AR SPTA1-associated HS. (C) Blood smear of the patient 5 years after total splenectomy, stable and without need of transfusions since the time of that surgery. Moderate anisopoikilocytosis and several spherocytes are still noted. Scale bar = 14 mm. Details on the ektacytometry assay and parameters can be found at https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/c/cancer-blood/hcp/clinical-laboratories/erythrocyte-diagnostic-lab/ektacytometry.

HS.(A)Ektacytometry of blood samples from the patient before and after splenectomy and from his parents. The patient had AR HS due to compound heterozygosity of SPTA1 c.4295del (p.L1432*), shared with the mom, and SPTA1 c.4339-99C>T, shared with the dad. The dad and the proband were also found to carry the PIEZO1 VUCS c.6205G>A (p.Val2069Met). The parents had a normal ektacytometry with no evidence of xerocytosis for the father, offering reassurance that the PIEZO1 VUCS is benign, while the patient after splenectomy had a typical HS curve. Before splenectomy, the patient was chronically transfused. Ektacytometry at that time was performed at a nadir before the next transfusion and 2 months after a previous one. Transfused RBCs have obviously modified the curve, giving a falsely normal Omin (ie, the hypotonic osmolality where the elongation index is minimal). The value of Omin provides information on the initial surface-to-volume ratio of the cell sample. A shift to the right reflects a decrease in the surface area/volume ratio and corresponds to increased osmotic fragility. (B) Blood smear of the patient about 18 months post partial splenectomy before starting to require transfusions again, demonstrating significant anisopoikilocytosis and polychromasia as well as many spherocytes, typical for AR SPTA1-associated HS. (C) Blood smear of the patient 5 years after total splenectomy, stable and without need of transfusions since the time of that surgery. Moderate anisopoikilocytosis and several spherocytes are still noted. Scale bar = 14 mm. Details on the ektacytometry assay and parameters can be found at https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/c/cancer-blood/hcp/clinical-laboratories/erythrocyte-diagnostic-lab/ektacytometry.

The child continued with chronic transfusions and chelation, but his iron overload appeared to be poorly controlled, and therefore a partial splenectomy was performed at 4 years of age, at least 2 weeks after pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccinations were administered.5 He remained transfusion-free for 18 months with an Hgb of 8.7 to 11 g/dL, but his anemia gradually worsened, requiring frequent transfusions again. A total splenectomy was performed at 7 years of age since the remaining splenic tissue had impressively regrown to 435 g, based on the pathology report. The patient has had no further transfusion requirement for the past 6 years, with a Hgb now in the 12.7 to 16.7 g/dL range, an absolute reticulocyte count (ARC) of 80 to 150 × 103/µL, and a resolved iron overload. Ektacytometry revealed the typical HS curve (Figure 1A); a blood smear at 5.5 years of age (before the total splenectomy) demonstrated many spherocytes and significant poikilocytosis and polychromasia, as expected with α-spectrin deficiency (Figure 1B).6 A recent blood smear, 5 years after the total splenectomy, showed an improved RBC morphology, although still with many spherocytes and moderate poikilocytosis (Figure 1C).

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS)

Genotype/phenotype correlations

HS, the most common of the RBC membrane disorders, is caused by mutations in the genes SPTA1, SPTB, ANK1, EPB42, or SLC4A1, leading to an RBC membrane skeleton deficient in α- or β-spectrin, ankyrin, protein 4.2, or band 3, respectively.6-9 These proteins build the scaffold and the vertical connections of the RBC membrane skeleton with the lipid membrane; their deficiency allows membrane loss and, consequently, the formation of spherocytes.6,9 Patients with autosomal dominant (AD) HS due to SLC4A1, SPTB, or ANK1 mutations or AR EPB42-HS present with a range of well-compensated hemolysis up to a moderately severe anemia (Hb <8 g/dL) with brisk reticulocytosis (>10%).6,10 Severe AR HS typically presents as a transfusion-dependent disease from early infancy and is most frequently due to a null SPTA1 variant in trans to an SPTA1 allele with the αLEPRA polymorphism, allowing for a small residual expression of normal α-spectrin, as in the case above.2,3 Rarely, a similar phenotype of AR HS may be due to a null ANK1 mutation in trans to a promoter or missense variant of ANK1 decreasing but not obliterating the incorporation of ankyrin into the membrane skeleton.11 With the advent of intrauterine transfusions for severe prenatal anemia, we now see the most severe HS cases, which used to be embryonal-lethal during the third trimester of pregnancy: these are cases due to biallelic SPTA1 null variants or homozygous SLC4A1 variants,3,12 which would remain transfusion-dependent even after splenectomy.

Clinical management

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, presenting as early as within the first 24 hours of life, is frequently the presenting sign of HS of any severity. Since fast-rising unconjugated bilirubin poses a risk of kernicterus, appropriate monitoring and treatment with phototherapy or, rarely, with exchange transfusion is needed. A transfusion requirement in mild or moderate spherocytosis may not develop for 2 to 3 weeks after birth, when the normal neonatal hyposplenism resolves. It is difficult to predict the phenotype of HS during the first year of life: transfusion dependency may continue during the first 9 months of life due to delayed erythropoietin response.13 During that time, evaluation for the genetic cause of the disease is attractive for physicians and families, to inform prognosis. Infants with an AD form of HS may benefit from erythropoietin administration to wean off transfusions faster.14

It is not rare for patients with mild HS who have compensated hemolysis to present later in life, after a viral infection, such as with Epstein-Barr virus or parvovirus B19; with a hemolytic or aplastic crisis; or with gallstones or splenomegaly on physical exam. Occasionally, toddlers are diagnosed with HS after referral to a hematologist because their Hgb does not improve with iron supplementation—one of the bright examples of why a complete blood count (CBC) for evaluation of anemia should always be associated with a reticulocyte count.

Spherocytes are prematurely destroyed in the spleen as they are impeded in passing through the interendothelial sinusoidal slits and eventually phagocytosed by the red pulp macrophages. Therefore, splenectomy has been used for decades as the standard of care for HS, with the aim of decreasing hemolysis and improving anemia. However, increased awareness of the postsplenectomy increased risks of sepsis; parasitic infections of erythrocytes; and, possibly, increased thrombophilia and atherosclerosis due to the rise in cholesterol,15,16 at least partially due to amelioration of the increased erythropoiesis, along with accumulation of follow-up data on the efficacy of partial splenectomy,17,18 has led to a more individualized approach recognizing the options of total vs partial vs no splenectomy. Therefore, it is currently recognized that splenectomy is not needed for all patients with HS. A form of splenectomy is indicated for patients with HS who have severe anemia requiring frequent transfusions or having compromised quality of life; partial splenectomy should be strongly considered as an option when the patient is younger than 5 years of age and for AD HS.5

In the clinical case above, in which the genetic diagnosis confirmed an SPTA1 null mutation in trans to αLEPRA, known to cause severe transfusion-dependent spherocytosis, splenectomy was the expected course of action. However, the additional finding of the PIEZO1 VUCS complicated the decision: if this variant was pathogenic, an additional component of HX could be causing intravascular hemolysis, leading to an increased risk of postsplenectomy thrombophilia.19 This is not an uncommon scenario since PIEZO1 has numerous VUCS. Parental studies to separate the variants and examine the associated phenotype by ektacytometry and RBC cation content are helpful to guide clinical decisions, as in our case. Given the concern regarding the patient's increasing iron overload despite chelation, the family and the primary hematologist decided to pursue splenectomy by the time he was 4. Thus, partial splenectomy was performed to mitigate hemolysis while preserving splenic immune function.5,7,17,18,20 Although partial splenectomy (leaving either the superior or inferior pole of the spleen) in HS is frequently a permanent solution,5 follow-up surgery with total splenectomy may be needed, especially in cases of SPTA1-associated AR HS.

Notable exceptions of splenectomy efficacy are the rare cases due to a complete deficiency of α-spectrin or band 3, who require either a lifelong program of transfusions and iron chelation or stem cell transplantion.3,12

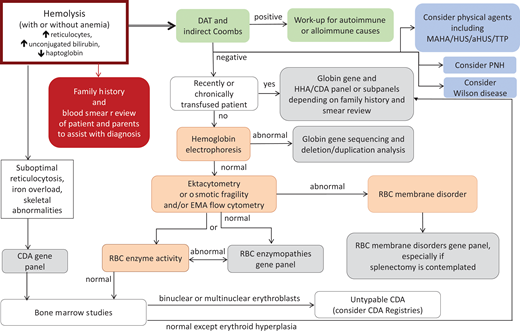

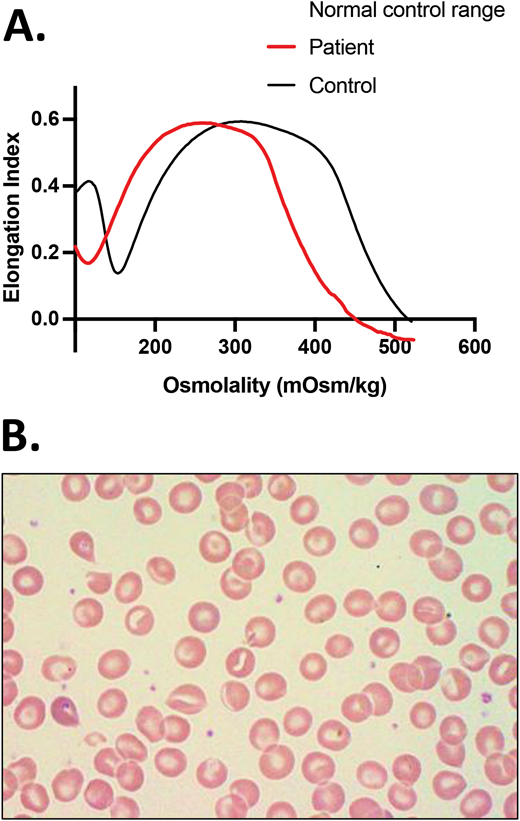

Not all spherocytes are due to HS. The history, blood smear, and ektacytometry in non-transfusion-dependent congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II (CDA-II) may closely resemble HS (Figure 2).4,21 Suboptimal reticulocytosis and high or high-normal ferritin values should trigger a genetic workup to explore this differential diagnosis. In addition, warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia frequently causes enough RBC membrane loss to resemble spherocytosis, both in erythrocyte morphology and ektacytometry. Therefore, the first tests recommended in the workup of a newly presenting hemolysis are direct and indirect antiglobulin tests (DAT and IAT) to evaluate for the possibility of an immune-mediated cause of hemolytic anemia since this radically alters management (Figure 3).

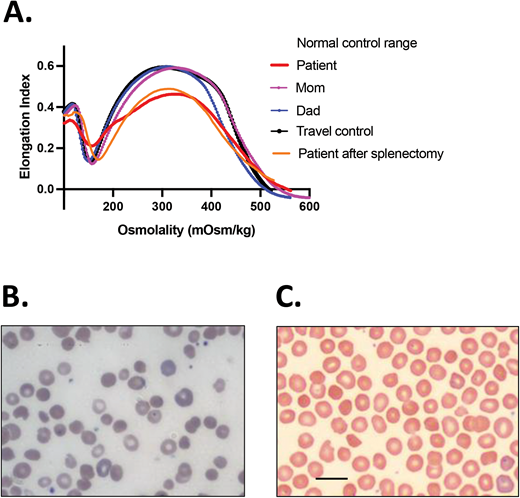

CDA-II is in the differential diagnosis for HS. A 4-year-old African American girl presented with DAT-negative, mild hemolytic anemia (Hgb, 10 g/dL) with a reticulocyte count of 2.4%, a normal ARC of 86 × 103/µL, and mild jaundice. She had a history of prolonged neonatal jaundice treated with phototherapy and no transfusion requirement. Ektacytometry showed a curve that resembled HS, and a blood smear showed spherocytes, marked poikilocytosis, and no polychromasia. Inadequate reticulocytosis and a ferritin of 80 ng/mL, at a generous level for her age with no concurrent inflammation, triggered further evaluation with sequencing of an HHA gene panel that revealed 2 SEC23B mutations, c.40C>T (p.R14W) and c.367-3A>G. Follow-up targeted sequencing of her parents confirmed that these 2 variants were in trans, causing CDA-II. Scale bar = 14 mm.

CDA-II is in the differential diagnosis for HS. A 4-year-old African American girl presented with DAT-negative, mild hemolytic anemia (Hgb, 10 g/dL) with a reticulocyte count of 2.4%, a normal ARC of 86 × 103/µL, and mild jaundice. She had a history of prolonged neonatal jaundice treated with phototherapy and no transfusion requirement. Ektacytometry showed a curve that resembled HS, and a blood smear showed spherocytes, marked poikilocytosis, and no polychromasia. Inadequate reticulocytosis and a ferritin of 80 ng/mL, at a generous level for her age with no concurrent inflammation, triggered further evaluation with sequencing of an HHA gene panel that revealed 2 SEC23B mutations, c.40C>T (p.R14W) and c.367-3A>G. Follow-up targeted sequencing of her parents confirmed that these 2 variants were in trans, causing CDA-II. Scale bar = 14 mm.

Proposed algorithm for laboratory workup of a patient presenting with hemolysis with or without anemia. In many cases of mild HS and most cases of PIEZO1-associated HX, anemia may be well compensated by reticulocytosis. Although our focus here is on RBC membrane disorders, the differential includes other causes of hemolytic disorders that are mentioned in this algorithm. Evaluation for autoimmune or, especially in an infant, alloimmune hemolytic anemia with DAT and IAT is the first testing recommended since such a diagnosis is frequently acute and evolving, requiring immediate action. Of note, warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children and occasionally adults with underlying immune dysregulation may be atypical and conventionally DAT-negative.52-54 Consideration should also be given to the possibility of MAHA, PNH, and Wilson disease. The cases described in this review, especially that presented in Figure 6, demonstrate utilization of this algorithm. A blood smear review of the patient and parents and attention to the RBC indices including MCV, MCHC, and RDW, along with hemolytic markers (unconjugated bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, haptoglobin—of note, haptoglobin is reliable after 6 months of life since earlier it may be low due to decreased production by the infant's liver rather than increased consumption) and ferritin and transferrin saturation to consider iron-loading inefficient erythropoiesis, can provide hints as to the differential diagnosis. In a non-chronically transfused patient, we suggest phenotypic evaluation considering the differential of globin disorders, followed by RBC membranopathies and enzymopathies. Rare causes of HHA such as unstable Hgb disorders and CDAs also need to be considered. When suboptimal reticulocytosis or iron overload or skeletal abnormalities are noted in a patient with hemolytic anemia, the possibility of CDA should be considered and pursued. The combination of blood smear review and osmotic gradient ektacytometry frequently helps to narrow the differential while alerting clinicians of rare possibilities. Osmotic gradient ektacytometry evaluates the deformability of RBCs as they are subjected to constant shear stress in a medium of increasing osmolality in a laser diffraction viscometer and is the reference technique for differential diagnosis of erythrocyte membrane and hydration disorders when a recent transfusion does not interfere with phenotypic evaluation of the patient.4 Flow cytometry with eosin-5′-maleimide binding of band 3 and Rh-related proteins is a rapid screening test for RBC membrane disorders characterized by membrane loss.55 Osmotic fragility is increased in HS and expected to be decreased in HX (however, it is reported as normal in patients with KCNN4 Arg352His mutation31 ). When the patient is recently or chronically transfused, as is typically the case for infants with HHA, genetic evaluation with clinically available NGS panels or research-based whole-exome sequencing or whole-genome sequencing may provide an accurate diagnosis necessary for appropriate management decisions. Laboratories that offer sequencing on genes or panels associated with HHAs and red cell membrane disorders can be found by searching the Genetic Testing Registry: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/. e.g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/all/tests/?term=RBC%20membrane%20disorders. aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; MAHA, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; RDW, RBC distribution width; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Proposed algorithm for laboratory workup of a patient presenting with hemolysis with or without anemia. In many cases of mild HS and most cases of PIEZO1-associated HX, anemia may be well compensated by reticulocytosis. Although our focus here is on RBC membrane disorders, the differential includes other causes of hemolytic disorders that are mentioned in this algorithm. Evaluation for autoimmune or, especially in an infant, alloimmune hemolytic anemia with DAT and IAT is the first testing recommended since such a diagnosis is frequently acute and evolving, requiring immediate action. Of note, warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in children and occasionally adults with underlying immune dysregulation may be atypical and conventionally DAT-negative.52-54 Consideration should also be given to the possibility of MAHA, PNH, and Wilson disease. The cases described in this review, especially that presented in Figure 6, demonstrate utilization of this algorithm. A blood smear review of the patient and parents and attention to the RBC indices including MCV, MCHC, and RDW, along with hemolytic markers (unconjugated bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, haptoglobin—of note, haptoglobin is reliable after 6 months of life since earlier it may be low due to decreased production by the infant's liver rather than increased consumption) and ferritin and transferrin saturation to consider iron-loading inefficient erythropoiesis, can provide hints as to the differential diagnosis. In a non-chronically transfused patient, we suggest phenotypic evaluation considering the differential of globin disorders, followed by RBC membranopathies and enzymopathies. Rare causes of HHA such as unstable Hgb disorders and CDAs also need to be considered. When suboptimal reticulocytosis or iron overload or skeletal abnormalities are noted in a patient with hemolytic anemia, the possibility of CDA should be considered and pursued. The combination of blood smear review and osmotic gradient ektacytometry frequently helps to narrow the differential while alerting clinicians of rare possibilities. Osmotic gradient ektacytometry evaluates the deformability of RBCs as they are subjected to constant shear stress in a medium of increasing osmolality in a laser diffraction viscometer and is the reference technique for differential diagnosis of erythrocyte membrane and hydration disorders when a recent transfusion does not interfere with phenotypic evaluation of the patient.4 Flow cytometry with eosin-5′-maleimide binding of band 3 and Rh-related proteins is a rapid screening test for RBC membrane disorders characterized by membrane loss.55 Osmotic fragility is increased in HS and expected to be decreased in HX (however, it is reported as normal in patients with KCNN4 Arg352His mutation31 ). When the patient is recently or chronically transfused, as is typically the case for infants with HHA, genetic evaluation with clinically available NGS panels or research-based whole-exome sequencing or whole-genome sequencing may provide an accurate diagnosis necessary for appropriate management decisions. Laboratories that offer sequencing on genes or panels associated with HHAs and red cell membrane disorders can be found by searching the Genetic Testing Registry: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/. e.g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/all/tests/?term=RBC%20membrane%20disorders. aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; MAHA, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; RDW, RBC distribution width; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Hereditary elliptocytosis and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis (HE/HPP)

Genotype/phenotype correlations

Hereditary elliptocytosis (HE) is caused by heterozygous mutations in SPTA1, SPTB, and EPB41, the genes encoding α-spectrin, β-spectrin, and protein 4.1R, respectively. HE-causing SPTA1 and SPTB variants are typically located in the spectrin tetramerization domain or, less frequently, along the chain or close to the junctional complex and produce a qualitative rather than quantitative defect in the spectrin tetramer; the altered spectrin chains incorporate into the membrane skeleton and weaken its horizontal scaffold.9,22 These variants have increased prevalence in malaria-endemic regions (up to 3% in West Africa), supporting the hypothesis that elliptocytosis confers a survival advantage to malaria. EPB41 mutations are responsible for fewer than 15% of HE cases; they lead to altered or deficient protein 4.1R, compromising the spectrin-4.1R-actin association at the junctions.7,23 Very rare cases of mild HE have been described due to homozygous nonsense mutations in GYPC, causing a complete deficiency of glycophorin C and, consequently, a partial deficiency of protein 4.1R in the junctional complex.

HE is characterized by elliptically shaped RBCs and is frequently asymptomatic with minimal or no hemolysis, normal Hgb, and a normal or borderline high reticulocyte count. Nevertheless, patients may present with exacerbated neonatal jaundice or develop episodic hemolysis with illnesses that cause hyperplasia of the reticuloendothelial system, eg, viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, bacterial infections, and malaria.7,23

Hereditary pyropoikilocytosis (HPP) is characterized by increased poikilocytosis, RBC fragmentation, and elliptocytes on the peripheral smear (Figure 4). The most common form of HPP is diagnosed in infants of African ancestry, who present with neonatal jaundice and frequently a transfusion requirement, and is due to an SPTA1 HE-causing mutation in trans to the SPTA1 splicing variant c.6531-12C>T, known as αLELY (low expression LYon).23,24 αLELY causes a 50% decrease in α-spectrin expression but is clinically silent in normal individuals even in the homozygous state since α-spectrin is produced well in excess. However, in trans to an HE-causing SPTA1 mutation, αLELY leads to an HPP phenotype because it allows for increased relative incorporation of the abnormal spectrin chain into the membrane skeleton. Of note, αLELY has a minor allele frequency of up to 25.5% (gnomad.broadinstitute.org); therefore, it is fairly common for an individual with nonhemolytic HE to have a child with HPP.

Transient infantile HPP. An African American girl presented within the first day of life after delivery at term with nonimmune hemolytic anemia and neonatal jaundice. She was treated with triple phototherapy but did not require RBC transfusion. (A) The blood smear of the patient with HPP showing marked anisocytosis and poikilocytosis with bizarre microcytes and fragmented cells along with elliptocytes (scale bar = 14 µm). (B) The blood smear of the mother, who had a normal Hgb and reticulocyte count, was notable for elliptocytes indicating HE. (C) Ektacytometry showed the trapezoid curve characteristic for HE and HPP with decreased deformability for both mother and patient. The patient's sample was sequenced by NGS on an RBC membrane gene panel, which revealed the SPTA1 HE-causing variant c.460_463insTTG (p.L155dup) as well as the SPTA1 c.6531-12C>T polymorphism known as αLELY. Targeted sequencing for these variants revealed that the mother was heterozygous for SPTA1 p.L155dup. The mother did not carry αLELY, which was presumably inherited by the father. The compound heterozygosity of an HE-causing SPTA1 mutation in trans to αLELY confirmed the diagnosis of infantile HPP. The child continued to have a mild anemia with reticulocytosis (Hgb, 10.2 g/dL with 3.8% reticulocytes) and poikilocytosis, with RDW up to 18.7% at her 2-year-old follow-up, but a CBC with reticulocyte count and blood smear at 5 years of age indicated transition to a nonhemolytic HE phenotype. RDW, RBC distribution width.

Transient infantile HPP. An African American girl presented within the first day of life after delivery at term with nonimmune hemolytic anemia and neonatal jaundice. She was treated with triple phototherapy but did not require RBC transfusion. (A) The blood smear of the patient with HPP showing marked anisocytosis and poikilocytosis with bizarre microcytes and fragmented cells along with elliptocytes (scale bar = 14 µm). (B) The blood smear of the mother, who had a normal Hgb and reticulocyte count, was notable for elliptocytes indicating HE. (C) Ektacytometry showed the trapezoid curve characteristic for HE and HPP with decreased deformability for both mother and patient. The patient's sample was sequenced by NGS on an RBC membrane gene panel, which revealed the SPTA1 HE-causing variant c.460_463insTTG (p.L155dup) as well as the SPTA1 c.6531-12C>T polymorphism known as αLELY. Targeted sequencing for these variants revealed that the mother was heterozygous for SPTA1 p.L155dup. The mother did not carry αLELY, which was presumably inherited by the father. The compound heterozygosity of an HE-causing SPTA1 mutation in trans to αLELY confirmed the diagnosis of infantile HPP. The child continued to have a mild anemia with reticulocytosis (Hgb, 10.2 g/dL with 3.8% reticulocytes) and poikilocytosis, with RDW up to 18.7% at her 2-year-old follow-up, but a CBC with reticulocyte count and blood smear at 5 years of age indicated transition to a nonhemolytic HE phenotype. RDW, RBC distribution width.

HPP can also be caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous HE-causing variants of SPTA1, SPTB, or EPB41 or a combination of SPTA1 and SPTB alleles with HE mutations.23,24 Hemolysis and poikilocytosis persist in those patients (true HPP), while the severity of the disease may vary from compensated hemolysis (eg, a case with combined SPTA1 p.L155dup and SPTB p.W2024R) up to transfusion dependency unresponsive to splenectomy (eg, a child with compound heterozygosity for spectrin St. Claude SPTA1 c.2806-13T>G,24 producing a truncated α-spectrin protein and a novel nonsense SPTA1 mutation p.R118* in trans).8 An example of true HPP due to homozygous SPTB p.F2014V mutation with transfusion dependency that responded well to splenectomy is detailed in Figure 5, to be contrasted with the example case of infantile HPP in Figure 4. My limited personal experience with these rare cases suggests that reticulocytopenia while on transfusions in severe HHA, such as the recessively inherited SPTA1-associated HS or severe true HPP, predicts a poor response to splenectomy. A better-informed rational approach to treatment is being developed, as we are gaining more insights into the specific genetic mutations causing these diseases.

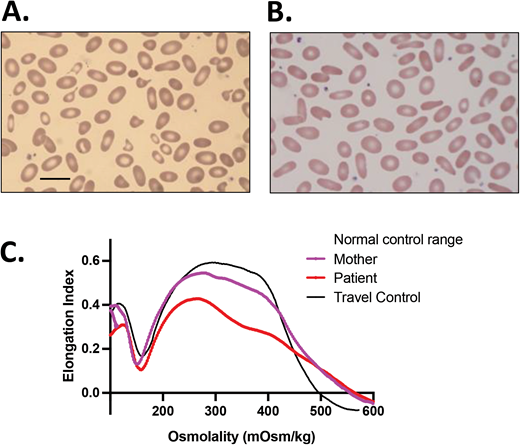

Persistent (true) HPP. A boy of Iranian descent presented with severe anemia since infancy. He remained transfusion dependent; therefore, his erythrocyte phenotype was not evaluable. (A) A blood smear of the father (practically identical with the blood smear of the mother) and (B) ektacytometry showing a trapezoid shape typical for HE for both parental samples indicated that they both had elliptocytosis. NGS on a panel of RBC membrane disorder genes revealed that the patient was homozygous for a novel missense mutation in the SPTB gene (c.6040T>G, p.F2014V), affecting the spectrin self-association site. Both parents were heterozygous for the same mutation.24

Persistent (true) HPP. A boy of Iranian descent presented with severe anemia since infancy. He remained transfusion dependent; therefore, his erythrocyte phenotype was not evaluable. (A) A blood smear of the father (practically identical with the blood smear of the mother) and (B) ektacytometry showing a trapezoid shape typical for HE for both parental samples indicated that they both had elliptocytosis. NGS on a panel of RBC membrane disorder genes revealed that the patient was homozygous for a novel missense mutation in the SPTB gene (c.6040T>G, p.F2014V), affecting the spectrin self-association site. Both parents were heterozygous for the same mutation.24

Clinical management

HE is frequently diagnosed incidentally on a blood smear review or during investigation for gallstones or splenomegaly or in a parent of an infant with neonatal jaundice diagnosed with HPP. Infants with the common form of HPP (SPTA1 HE-variant in trans to αLELY) may have moderate to severe hemolytic anemia requiring frequent transfusions early in life, but the phenotype improves after the first 1 to 2 years, evolving to typical HE.7 HPP due to biallelic HE-causing mutations may present with mild to severe chronic anemia with long-term transfusion dependence. Most but not all of the cases with severe hemolysis and a chronic transfusion requirement respond to splenectomy.8,24

Hereditary xerocytosis (HX)

Genotype/phenotype correlations

HX, also called dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis, is an AD disease caused by mutations in PIEZO1 or KCNN4,25-32 coding respectively for the mechanosensitive cation channel PIEZO1 and the calcium ion-activated potassium (K+) channel known as the Gardos channel. HX RBCs have an abnormal K+ leak not compensated by a proportional intracellular sodium (Na+) gain, leading to cellular dehydration. Pseudohyperkalemia may be noted if analysis of electrolytes in blood specimens is delayed. HX is characterized by intravascular hemolysis and intrahepatic RBC destruction that persists after splenectomy (therefore, splenectomy is not only dangerous but also ineffective as an HX treatment) as well as iron overload disproportionate to the transfusion history.19,33 Significant phenotypic variability exists, probably due to the large number of causative variants, coinheritance of variants in other genes affecting RBC phenotype,34 and multiple mechanisms contributing to the pathogenesis.35 HX patients may present with mild to moderate hemolytic anemia, usually due to an aminoterminal PIEZO1 mutation or KCNN4 variants, or, with fully compensated hemolysis, due to the most common carboxyterminal PIEZO1 variants (Figure 6).19 Despite the RBC dehydration, mean cellular volume (MCV) is high normal to normal in HX, likely due to the effects of the mutated channels in erythropoiesis.36 Cases with polycythemia despite hemolysis have also been reported,37 pointing to the hypothesis that patients with HX may have increased erythropoietic drive for their level of Hgb because of relatively low 2,3-DPG levels and consequently high Hb-oxygen affinity and exacerbated tissue and renal hypoxia.38,39 Hepatic and/or myocardial iron overload may be the presenting sign for some patients when not diagnosed before adulthood. Evaluating for hemochromatosis gene mutations is recommended since this may alter clinical prognosis and care. Iron overload may also be accelerated in cases of KCNN4-HX,19 as well as in cases of aminoterminal PIEZO1 pathological variants such as the p.V598M (personal communication on 2 patients in their early 20s with preferential and severe myocardial iron overload).

HX due to heterozygousPIEZO1 mutation. A European American girl, born at term, developed neonatal hyperbilirubinemia that prevented discharge from the nursery for 4 days while receiving treatment with phototherapy. Scleral icterus was again noted at 10 months of age, and a CBC indicated reticulocytosis but a normal Hgb. She continued to have chronic hemolysis and jaundice and had an extensive workup including negative DAT, normal Hgb electrophoresis, RBC enzyme activity testing showing normal or increased activity, osmotic fragility testing that was (probably mistakenly) reported as normal rather than as decreased, alpha and beta globin genetic testing that revealed no mutation or copy number variation, a negative PNH screen by flow cytometry, and bone marrow studies showing erythroid hyperplasia, no dyserythropoiesis, and markedly increased iron stores. (A) At 10 years of age, she had osmotic gradient ektacytometry performed that demonstrated a typical HX curve, with left shift due to decreased Omin and Ohyp (Figure 2A). The CBC at the time indicated an Hgb of 14.2 g/dL, an MCV of 96 fl, an MCH of 36.5 pg, an MCHC of 37.9 g/dL, a reticulocyte count 16.9%, and an ARC of 643 × 103/µL. (B) A blood smear was significant for polychromasia, macrocytosis, and occasional stomatocytes, target cells, and dense fragmented cells. Of note, sometimes the blood smear may be deceptively normal, with only a few target cells and no stomatocytes. A determination of the RBC intracellular cation confirmed a reduced K+ content without a corresponding increase in Na+ content. NGS for an RBC membrane disorder panel revealed 1 of the most common PIEZO1 variants (c.7367G>A, p.R2456H) causing HX. PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

HX due to heterozygousPIEZO1 mutation. A European American girl, born at term, developed neonatal hyperbilirubinemia that prevented discharge from the nursery for 4 days while receiving treatment with phototherapy. Scleral icterus was again noted at 10 months of age, and a CBC indicated reticulocytosis but a normal Hgb. She continued to have chronic hemolysis and jaundice and had an extensive workup including negative DAT, normal Hgb electrophoresis, RBC enzyme activity testing showing normal or increased activity, osmotic fragility testing that was (probably mistakenly) reported as normal rather than as decreased, alpha and beta globin genetic testing that revealed no mutation or copy number variation, a negative PNH screen by flow cytometry, and bone marrow studies showing erythroid hyperplasia, no dyserythropoiesis, and markedly increased iron stores. (A) At 10 years of age, she had osmotic gradient ektacytometry performed that demonstrated a typical HX curve, with left shift due to decreased Omin and Ohyp (Figure 2A). The CBC at the time indicated an Hgb of 14.2 g/dL, an MCV of 96 fl, an MCH of 36.5 pg, an MCHC of 37.9 g/dL, a reticulocyte count 16.9%, and an ARC of 643 × 103/µL. (B) A blood smear was significant for polychromasia, macrocytosis, and occasional stomatocytes, target cells, and dense fragmented cells. Of note, sometimes the blood smear may be deceptively normal, with only a few target cells and no stomatocytes. A determination of the RBC intracellular cation confirmed a reduced K+ content without a corresponding increase in Na+ content. NGS for an RBC membrane disorder panel revealed 1 of the most common PIEZO1 variants (c.7367G>A, p.R2456H) causing HX. PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Clinical management

Genetic counseling and close monitoring of pregnancies should be provided when either parent has HX because of the risk of perinatal edema and nonimmune hydrops fetalis.19

Splenectomy is contraindicated in HX due to PIEZO1 mutations because it predisposes patients to life-threatening venous and arterial thromboembolic complications, reported to happen within a month up to 28 years post splenectomy.19,40,41 Although no thrombotic complications were observed after splenectomy in 12 patients with KCNN4-associated HX after follow-up for 2 to 44 years,19,31 splenectomy should be avoided anyway since it provides no therapeutic benefit in either PIEZO1- or KCNN4-associated HX because intravascular and intrahepatic RBC destruction persists after splenectomy.33

Management is currently focused on supportive care for anemia and hemolysis complications and on preventive monitoring to quantitate and treat iron overload as needed. Screening with ferritin and transferrin saturation should be followed (even with a moderate increase in ferritin) by T2* magnetic resonance imaging of the liver and heart. Iron overload is much more easily and effectively treated with chelation when diagnosed early. Phlebotomy has also been used to address HX-associated iron overload. However, based on the fact that hemochromatosis in HX is multifactorial and includes excessive erythropoiesis causing increased erythroferrone that suppresses hepcidin as well as the direct suppression of hepcidin,35,42 the efficacy of phlebotomy to treat iron overload in HX needs further evaluation.43

Specific medications for the treatment of HX are not clinically available. A promising option may be a specific inhibitor for the Gardos channel, senicapoc, since KCNN4 is the final common mediator of RBC dehydration in HX.8,44 Senicapoc was shown to be well tolerated in a phase 3 trial in sickle cell disease, where it reduced RBC dehydration and hemolysis and increased Hgb levels.45 A phase 1/2 “proof-of-concept study of senicapoc in patients with familial dehydrated stomatocytosis caused by the V282M mutation in the Gardos (KCNN4) channel” has been posted on clinicaltrials.gov and is currently recruiting.

Overhydration syndromes

Genotype/phenotype correlations

Genetic etiology in overhydration syndromes is variable, along with a phenotype of mild to severe hemolytic anemia.46,47 Blood smear is remarkable for abundant stomatocytes; RBC physiology is characterized by a large net increase in intracellular Na+ and water not adequately compensated by a decrease in K+. MCV is typically increased, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) is decreased. Osmotic fragility is increased, and ektacytometry is right-shifted.

The most severe form of overhydrated hereditary stomatocytosis is caused by heterozygous missense mutations in RHAG, the gene coding for the red cell ammonium transporter rhesus- associated glycoprotein; both mutations described so far (p.Phe65Ser and p.Ile61Arg) alter amino acids lining the putative transport channel, making it permeable to Na+ ions.48-50

Cryohydrocytosis, Southeast Asian ovalocytosis, and band 3 Ceinge are caused by certain heterozygous mutations in SLC4A1, which alter the band 3 channel to mediate cation leak in cold temperatures.46,47 Patients with stomatin-deficient cryohydrocytosis, caused by mutations in SLC2A1 coding for glucose transporter type 1, present with moderate hemolytic anemia, cataracts due to the altered cation permeability of the lens, and neurological disorders caused by disrupted glucose transport.

Clinical management

Management is supportive for anemia and hemolysis complications. Splenectomy is usually partially effective in reducing hemolysis, but it carries a high risk of thromboembolic complications and pulmonary hypertension.40,41 Prophylactic anticoagulation should be considered in patients who have inadvertently been splenectomized.

Conclusions

Decades of research on the molecular pathogenesis of RBC membrane disorders have culminated,9,51 upon the advent of NGS over the last 10 years, in a high success rate of genetic diagnosis for patients with such diseases. Genetic diagnosis is highly beneficial for transfusion-dependent patients and likely prudent to consider before proceeding to the irreversible treatment of splenectomy, which is not always effective or safe. Increased information on genotype-phenotype correlation along with the current wider availability of partial splenectomy calls for a new consensus statement of experts in the field on updated management guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL152099.

We are grateful to the patients, families, and referring physicians participating in our diagnostic studies of hereditary hemolytic anemia and to the teams of the Cincinnati Children's Erythrocyte Diagnostic Laboratory and Molecular Genetics Laboratory for their contribution to the diagnostic studies of cases presented in the text and figures.

Clinical outcomes reported in some of these cases are based upon personal communication with Drs. Marya Almansoori, Jeanne Boudreaux, Morgan McLemore, Charles Quinn, and Audrey Woerner.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Theodosia A. Kalfa: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Theodosia A. Kalfa: nothing to disclose.