Abstract

Relapse of cancer remains one of the primary causes of treatment failure and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). A multitude of approaches have been used in the management of posttransplant relapse. This review focuses on recent data with cellular therapies designed to treat or prevent posttransplant relapse of hematologic malignancies, although many of these therapeutic approaches also have applications to solid tumors and in the nontransplant setting. Currently available cell therapies include second transplant, natural killer cells, monocyte-derived dendritic cell vaccines, and lymphocytes via donor lymphocyte infusion, antigen-primed cytotoxic T lymphocytes, cytokine-induced killer cells, marrow-infiltrating lymphocytes, and chimeric antigen receptor T cells. These treatment options offer the prospect for improved relapse-free survival after HSCT.

Learning Objectives

Understand the biologic basis, potential advantages, and risks of specific cell-based cancer therapies

Gain knowledge about recent results of cellular therapies used in the prevention and treatment of relapse after allogeneic HSCT

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and the graft-versus-tumor effect are an important part of curative treatment of many cancers, most notably hematologic malignancies.1 Despite the curative advantage of HSCT in comparison with chemotherapy alone for high-risk disease, relapse remains the primary cause of posttransplant treatment failure and mortality.2-4 Additionally, the use of HSCT comes with significant risks, including transplant-related mortality, infection, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).1,4

A number of efforts have been put forward in recent years to specifically address the challenge of relapse after HSCT. The National Cancer Institute held international consensus conferences on the biology, prevention, and treatment of relapse after HSCT in hematologic malignancies in 2009 and 2012.2 A third international workshop in this area was held in Hamburg, Germany in November of 2016, with conference proceedings currently in the publication process (www.relapse-after-hsct2016.de). There are a number of new pharmaceutical and cellular therapy approaches being investigated to prevent and treat relapse after HSCT,5 some of which are particularly applicable to those patients with limited ability to tolerate cytotoxic chemotherapy or HSCT due to age, performance status, and/or comorbid conditions.3

Cellular therapies are being investigated in a wide variety of cancers including in the nontransplant setting. However, this review focuses on cellular therapy for hematologic malignancies, where the most clinical progress has been achieved to date, and the applications of such to treat or prevent relapse after HSCT.

Biology of relapse and cellular therapy

There has been great progress made in the elucidation of the biologic mechanisms that underlie relapse after HSCT and in the development of approaches to counter or overcome those mechanisms in an attempt to prevent or treat posttransplant relapse. Relapse in this setting represents malignant cells that can escape both from the cytotoxic injury associated with pretransplant conditioning and from the immunologic control created by posttransplant immune reconstitution.6 With all of the therapies being explored, prevention of relapse may ultimately prove to be the most feasible and effective means of improving relapse-free survival after allogeneic HSCT.5

Malignant cells can recruit immunosuppressive cells and produce or induce soluble inhibitory factors that create a tumor microenvironment in which cancers are able to avoid immune-mediated killing. This tumor-permissive environment dampens effective immune responses and blocks the function of normal immune effector cells. This can include dendritic cell dysfunction, defective tumor antigen presentation, checkpoint pathway activation, resistance of tumor cells to death through altered metabolism, and more.7,8 Additionally, direct contact of leukemia cells with bone marrow stromal cells can trigger intracellular signals that promote cell-adhesion–mediated drug resistance.9

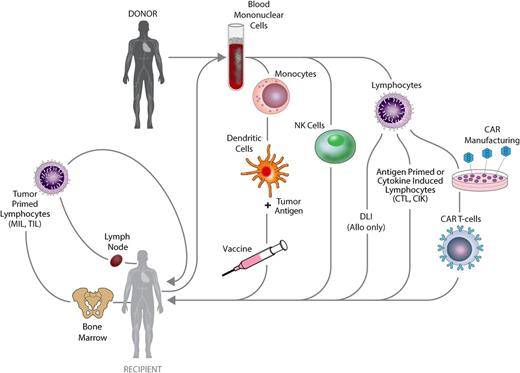

Cell-based therapies have the potential to overcome malignant cell therapy resistance and circumvent or change the tumor microenvironment allowing for effective tumor control. Both autologous and allogeneic approaches have been developed, as depicted in Figure 1. Cell therapies currently used in the peritransplant period include HSCT itself, subsequent donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), cytokine-induced killer cells (CIKs), marrow-infiltrating lymphocytes (MILs), chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CARTs), monocyte-derived dendritic cell vaccines, and natural killer cells (NKs). HSCT and DLI have been the most commonly used and have the longest track record. Of the more recently developed approaches, efficacy has been limited, with the exception of CART for B-cell malignancies (Table 1).1,3 The ideal cellular therapy should have potent antitumor activity with limited nonspecific off-target toxicity. Figure 2 depicts the relative therapeutic potential of various cellular therapies used to combat posttransplant relapse.5 To maximize efficacy and optimize outcomes, combinations of cellular therapies and/or other treatment modalities will likely be needed.7 Molecular profiling of tumor-associated leukocytes has revealed distinct subsets prognostic for cancer survival.10 This raises the prospect that such an approach might be used in the setting of posttransplant cellular immunotherapy as a biomarker for clinical response, to select immune effector subsets for therapeutic use that are predicted to improve clinical outcome and to assess immune effector cell subset distribution and activation to better understand mechanisms of treatment response and resistance.

Generation of cellular therapies for the treatment or prevention of relapse following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIK, cytokine-induced killer; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; MIL, marrow-infiltrating lymphocyte; NK, natural killer; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte.

Generation of cellular therapies for the treatment or prevention of relapse following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIK, cytokine-induced killer; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; MIL, marrow-infiltrating lymphocyte; NK, natural killer; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte.

Reviewed and published CART studies in hematologic malignancies

| Target antigen (diseases treated) . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | Results . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | ||||

| (ALL) | 9 | 264 | 30%-90% CR | Mixture of vectors and costimulatory domains, some CD19− relapses, many went on to subsequent HSCT where there were no CD19− relapses |

| (CLL) | 7 | 31 | 20%-75% CR, 15%-30% PR | Lymphodepletion improved outcomes |

| (NHL) | 13 | 151 | 40%-100% CR | Mixture of histologies, vectors, and costimulatory domains, no GVHD seen, lymphodepletion improved outcomes |

| (MM) | 1 | 1 | Stringent CR | CART given after auto-HSCT |

| CD20 (NHL) | 1 | 4 | 1 PR, 2 remained in remission | Used in consolidation or for residual disease |

| CD22 (NHL) | 1 | 6 | 1 CR, 2 SD | Most with CD19− relapse |

| CD30 (HOD) | 2 | 27 | 1 CR, 8 PR, 10 SD, 8 PD | |

| CD33 (AML) | 1 | 1 | Transient reduction in blasts | |

| CD123 (AML) | 1 | 1 | Transient reduction in blasts | |

| BCMA (MM) | 1 | 11 | 1 VGPR, 2 SD, 1 CR | Improved response with higher-dose cohort |

| LeY (AML) | 1 | 4 | 1 transient CR, 1 transient reduction in blasts, 2 SD | CART could be detected in sites of extramedullary disease |

| Target antigen (diseases treated) . | No. of studies . | No. of patients . | Results . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | ||||

| (ALL) | 9 | 264 | 30%-90% CR | Mixture of vectors and costimulatory domains, some CD19− relapses, many went on to subsequent HSCT where there were no CD19− relapses |

| (CLL) | 7 | 31 | 20%-75% CR, 15%-30% PR | Lymphodepletion improved outcomes |

| (NHL) | 13 | 151 | 40%-100% CR | Mixture of histologies, vectors, and costimulatory domains, no GVHD seen, lymphodepletion improved outcomes |

| (MM) | 1 | 1 | Stringent CR | CART given after auto-HSCT |

| CD20 (NHL) | 1 | 4 | 1 PR, 2 remained in remission | Used in consolidation or for residual disease |

| CD22 (NHL) | 1 | 6 | 1 CR, 2 SD | Most with CD19− relapse |

| CD30 (HOD) | 2 | 27 | 1 CR, 8 PR, 10 SD, 8 PD | |

| CD33 (AML) | 1 | 1 | Transient reduction in blasts | |

| CD123 (AML) | 1 | 1 | Transient reduction in blasts | |

| BCMA (MM) | 1 | 11 | 1 VGPR, 2 SD, 1 CR | Improved response with higher-dose cohort |

| LeY (AML) | 1 | 4 | 1 transient CR, 1 transient reduction in blasts, 2 SD | CART could be detected in sites of extramedullary disease |

Data from Kenderian et al1 and supplemented with PubMed search (May 2017).

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen; CART, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; CLL, chryonic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete response; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HOD, Hodgkin lymphoma; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; VGPR, very-good partial remission.

Theoretical relative therapeutic potential of cellular therapies for relapse. The shaded quadrant represents the zone of optimal specificity with respect to tumor vs off-target cytotoxic tissue damage, which maximizes antitumor potency and minimizes cell-mediated morbidity. Conventional DLI and second SCT (depicted in red) are the currently available cell-based treatments for relapse, against which novel therapies (blue) will be judged. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIK, cytokine-induced killer; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; MiAg, minor histocompatibility; NK, natural killer; SCT, stem cell transplantation; TAA, tumor-associated antigen. Reprinted from de Lima et al5 with permission (published under the terms of the Creative Commons attribution–noncommercial–no derivatives license [CC BY NC ND]).

Theoretical relative therapeutic potential of cellular therapies for relapse. The shaded quadrant represents the zone of optimal specificity with respect to tumor vs off-target cytotoxic tissue damage, which maximizes antitumor potency and minimizes cell-mediated morbidity. Conventional DLI and second SCT (depicted in red) are the currently available cell-based treatments for relapse, against which novel therapies (blue) will be judged. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIK, cytokine-induced killer; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; MiAg, minor histocompatibility; NK, natural killer; SCT, stem cell transplantation; TAA, tumor-associated antigen. Reprinted from de Lima et al5 with permission (published under the terms of the Creative Commons attribution–noncommercial–no derivatives license [CC BY NC ND]).

Second HSCT

HSCT represents the original cellular immunotherapy of cancer, with reactive T cells responsible for a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.3 A second transplant may be considered to treat relapse after a first HSCT, although success of a second procedure is unlikely without obtaining remission (preferably minimal residual disease [MRD] negative), and many patients will not be able to achieve that level of disease control. However, relapse-free survival has been achieved in 20% to 45% of the select group that can undergo a second HSCT.11,12 As with the first transplant, complications include treatment-related mortality, infection, GVHD, and relapse,3,13 with higher risks after second HSCT such that nonrelapse mortality can exceed 40%.5

Factors such as favorable performance status, longer duration of remission after first HSCT, minimal disease status at time of second HSCT, and younger age have all been associated with improved outcomes.5,14 More favorable outcomes are also seen when reduced-ntensity conditioning regimens are used to decrease treatment-related morbidity and mortality.11,12,14 DLI and/or cytokines have been used in an attempt to enhance the GVL effect and reduce the risk of relapse after second transplants.5 Whether a different donor from the first HSCT should be used has been a topic of interest, with no proven advantage to using a new donor.5,14 In summary, there is a role for second HSCT to manage posttransplant relapse in selected patients, but failure to obtain deep remission by most patients and significant treatment-associated toxicity limit broad application. Thus, one of the most important strategies to improve relapse-free survival after HSCT is to develop approaches to prevent posttransplant relapse from occurring in the first place.14

Lymphocyte-based cellular therapy

As donor T cells are responsible for potent GVL reactions,3 the use of lymphocytes has led the way in the development of specific cellular therapy for cancer. Lymphocytes may be obtained from patients for autologous use or from allogeneic donors; they may be harvested from various sites (eg, peripheral blood, bone marrow) and expanded, selected, manipulated, and/or gene modified ex vivo, all of which define the unique role that DLI, CTL, CIK, MIL, and CART cellular therapies play.

Donor lymphocyte infusion

Unmanipulated, unselected DLI is a well-established therapy in the management of posttransplant relapse,13 and many newer cellular therapies have been judged in relationship to outcomes from DLI and second HSCT.5 The efficacy of DLI is limited by high disease burden and proliferative rate and also possibly by immune escape mechanisms underlying relapse.5 Individuals with low-risk disease (chronic myelogenous leukemia [CML] in chronic phase, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, low-grade lymphomas) have better outcomes after DLI in comparison with those with higher-risk disease (3-year overall survival, 50%-70% vs 20%-40%, respectively).15 DLI is most effective in patients with CML in molecular relapse or chronic phase (>80% complete response rate), although the advent of BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors has reduced the need for DLI in this setting. Prolonged relapse-free survival has been observed in some patients with high-risk disease in whom complete remission is achieved prior to DLI.3

DLI can be used either as treatment, or more optimally in a prophylactic or preemptive manner for mixed chimerism and/or presence of MRD.13 Combination approaches have been used to try to improve the results of DLI, for example, α-interferon and other cytokines to augment GVL, lymphodepletion, targeted agents, and checkpoint inhibitors.3,5,13,16 The primary complication of DLI is GVHD. Methods designed to reduce the risk of or reverse GVHD include chemotherapy, immunosuppressive medications, and the use of selected T-cell subsets and/or modified T cells (eg, suicide gene insertion) as the DLI product.3,17-19

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

Lymphocyte clones that are directed against target tumor-associated antigens can be expanded and used to treat or prevent malignancy after HSCT. Probably the most experience is with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific CTLs in the setting of posttransplant EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease and lymphomas.20 CTL clones can be derived and expanded ex vivo from patients or healthy donors. These can be directed toward an array of intracellular or surface antigens through priming in vivo (ie, endogenous antigen exposure) or ex vivo (ie, antigen priming in culture). Antigens that have been used to generate leukemia-reactive CTLs include leukemia-associated antigens (eg, WT1, PR1, PRAME), leukemia-specific antigens (eg, BCR/ABL), or minor histocompatibility antigens (eg, HA-1, HA-2).13,17,21-23 T-cell receptors from allogeneic donor leukemia-reactive CTLs can be cloned into autologous T cells for management of posttransplant relapse.13 Notably, expanded γ-δ T cells have been shown to be reactive against cytomegalovirus and leukemia blasts, raising the possibility that adoptive cell therapy could be used to reduce the risk of both posttransplant cytomegalovirus reactivation and leukemia relapse.24

This type of cellular therapy has been shown to be feasible, safe, and, in some cases, effective. However, CTL effectiveness can be impacted by the immunogenicity of the specific antigen, the affinity of the T-cell receptors, the presence of suppressive cells such as T regulatory cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as well as secreted factors from the tumor microenvironment.7 Furthermore, CTL generation is logistically challenging, time-consuming, and not always successful.5

Cytokine-induced killer cells

This form of cell therapy consists of a polyclonal T-cell population that has been expanded in vitro under cytokine stimulation. In contrast to many other T-cell therapies, CIK-mediated cytotoxicity is HLA unrestricted and T-cell receptor independent.3 These cells have been demonstrated to be safe with limited toxicity, but they may induce GVHD and, to date, only limited efficacy has been reported.3,5,17,25,26 Their use more than likely will be best prior to overt relapse or in combination with other therapies.5

Marrow- and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

The lymphocytes that reside in the bone marrow, or MILs, are a population with higher endogenous tumor specificity than those found in the periphery. They include antigen-experienced T cells that home to and remain in the bone marrow microenvironment in proximity to many antigen-presenting cells (APCs).27 As a result, MILs are highly enriched for long-lived memory T cells. They are being studied to treat hematologic malignancies after HSCT and are being considered as a source for genetically modified T cells that could theoretically reduce the risk of relapse from antigen escape variants.27 MILs are also being examined in cancers without bone marrow involvement. In contrast to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which have been exploited for cellular therapy of solid tumors, MILs are readily obtainable from patients and successfully expand in culture in 7 to 10 days.27 TILs have also been used to combat posttransplant relapse of lymphoma.28

Chimeric antigen receptor T cells

One of the most promising cellular therapy approaches is the use of T cells engineered to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), which can achieve high response rates and long-term antitumor activity (Table 1).1,3,5 The CAR, introduced through lentiviral or retroviral transduction, transposon/transposase systems, or electroporation, is a synthetic protein with 3 distinct domains: an extracellular monoclonal antibody–derived single-chain variable fragment; a transmembrane domain; and an intracellular T-cell signaling system.1 This allows for specific binding of cancer-associated surface antigens, which trigger T-cell activation and killing without the need for antigen processing and presentation.3

First-generation CAR T cells (CARTs), without a costimulatory molecule, had good specificity with limited clinical activity and persistence. Second-generation CARTs include a costimulatory signal that improves activation and effector function. Most clinical trials reported thus far have used second-generation CARTs. Third-generation CARTs with >1 costimulatory molecule and fourth-generation CARTs that include other modifications (eg, suicide switches) are in early clinical trials or preclinical development. The costimulatory mechanism used provides distinct functional capacities. For example, the use of CD28 costimulation can result in very potent effector function, but with reduced persistence in comparison with 41BB costimulation.1

CART manufacturing involves collection of either autologous or allogeneic T cells via leukapheresis followed by T-cell enrichment and stimulation in culture, CAR transgene introduction, ex vivo T-cell expansion, and subsequent infusion into the patient.1,29 CART clinical trials have been conducted in most hematologic malignancies as well as in various solid tumors, with Table 1 summarizing results of studies published to date for hematologic malignancies.1,30-44 MRD− complete response rates of 90% have been achieved in B-lineage disease using CARTs that target CD19, with leukemia-free survival rates of ∼50% at 1 year.38,43 The US Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first CART therapy, which targets CD19 for children and young adults with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).45 This technology has not yet been developed for T-cell malignancies, as the CARTs could kill each other (so-called “fratricide”) and also could leave patients with severe, prolonged T-cell depletion.3

Side effects of CART therapy can be quite significant and include cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, and B-cell aplasia resulting in hypogammaglobinemia.1,3 CRS is a syndrome that can include high-grade fevers, refractory hypotension, capillary leak, respiratory failure, and other end-organ dysfunction.46 This multisystem process can be life threatening, although it can respond quickly to anticytokine therapy, most notably interleukin-6 blockade and/or corticosteroids.1,46 Importantly, intervention for CRS does not seem to impact the effectiveness of CART therapy. Neurotoxicity can include headaches, generalized encephalopathy, aphasia, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, and obtundation. In most cases, the symptoms resolve spontaneously, although fatal cerebral edema has occurred rarely.1

Additional limitations include the time needed to generate CARTs, which varies based on the specific construct and manufacturing process, CART rejection, and antigen escape with loss of the CAR-targeted epitope resulting in relapse.1 This latter problem might be overcome by dual antigen targeting. Other approaches to optimize CART therapy are under development including engineering universal “off-the-shelf” constructs.47 Whether CART therapy should be used as a bridge to second HSCT or whether it can provide definitive therapy alone remains a question.1 In the treatment of B-lineage ALL, loss of B-cell aplasia appears to presage relapse; thus, a reasonable strategy might be to closely monitor and intervene with HSCT at early signs of CART loss or B-cell recovery.

To date, the largest published studies of CARTs after transplant have targeted CD19 in children with ALL. In a series of 21 patients, 8 of whom had relapsed post-HSCT, 76% had CRS (29% grades 3/4) and 29% developed neurotoxicity with a 67% complete response rate including a 60% MRD− complete response rate.43 In another series of 30 patients, 18 with relapse after HSCT, all patients had CRS (27% severe) and 43% had neurotoxicity with a 90% complete response rate.38 In a recent report of 45 children with ALL, 28 with posttransplant relapse, 93% of patients developed CRS (23% severe), 49% developed neurotoxicity (21% severe), and 93% of those who received the CART product achieved an MRD− remission.44 Only 1 of these 45 patients with prior HSCT was reported to develop GVHD after CART, which was grade 3 confined to skin.44

Monocyte-based cellular therapy

Monocyte-derived dendritic cells are potent antigen-presenting cells that educate T cells to recognize tumor antigens, which results in the production of tumor-specific CTLs. These CTLs can then kill tumor cells that express the target antigen, similar to antigen-primed CTLs.3 Most trials of dendritic cell vaccines to date have been conducted in the autologous setting, although this approach has also been adapted for allogeneic use.23,48 Multiple antigen sources can be used in dendritic cell vaccines, including tumor cell lysates, apoptotic bodies, exosomes or fusions, tumor-derived RNA, and tumor-targeted proteins or peptides.7,23 Leukemia-associated antigens, such as those mentioned in the section on CTLs, have been most frequently used, especially WT1.3,48,49 Although a number of studies have shown feasibility and safety, clinical and immunologic responses have been infrequent and unpredictable.48

NK-based cellular therapy

NK cells are CD56+, CD3− innate immune effectors that are capable of responding to and eradicating pathogen-infected and tumor cells rapidly and without recruitment of T cells.3 NK-cell infusions have been studied in the autologous and allogeneic settings where they have been generally well tolerated.50 Activity has been relatively modest, although reductions in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) relapse have been reported.3 The antitumor effect associated with NK cells has been best described in the setting of HSCT, particularly in regard to killer immunoglobulin receptor biology where donor-recipient mismatched alloreactive NK cells can mediate a GVL effect. Importantly, GVHD has been observed in clinical trials of both HLA-matched and haploidentical allogeneic NK-cell therapy after HSCT.50,51 Additional attempts to engage NK cells include the use of bispecific or trispecific antibodies and the redirection of NK cells through a CAR.3

Conclusion

When patients relapse after first allogeneic HSCT, the administration of cellular therapy may allow for additional disease control and, in some cases, long-term survival. Second transplant, DLIs, CTLs, CIKs, MILs, CARTs, vaccines, and NK cells have all been used, in many cases with acceptable safety profiles and some level of activity and even efficacy. Second transplant can be considered standard of care for patients with adequate clinical status who attain good remission after relapse (usually patients with longer initial posttransplant remission durations), whereas DLI is considered standard for CML in chronic phase or molecular relapse with tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy resistance. Of the other novel cellular therapeutic approaches, CART has set new standards for high response rates in patients with posttransplant relapse of B-cell malignancies. Table 2 summarizes current clinical trials in progress, as evidence of this rapidly expanding field. Ultimately, combinations of cellular therapies, or the combination of these therapies with novel agents such as epigenetic modifying agents, checkpoint inhibitors, and/or standard chemotherapy will likely be necessary to achieve the greatest benefits. Newer cellular therapies will continue to be developed and enter clinical trials over the next few years. Although cellular immunotherapy approaches will likely improve outcomes for patients undergoing HSCT in the future, it is critically important that the most effective of these approaches be studied earlier in the course of therapy with the goal to reduce the risk of relapse after primary therapy or salvage HSCT. Approaches to reduce associated risks and ameliorate specific toxicities (eg, CRS), along with standardization and improvements in manufacturing processes as well as cost reduction will be essential to incorporate cellular therapy into upfront regimens. Ongoing studies will be necessary to best determine how each of these therapies fit into future treatment algorithms, which in turn will facilitate broader application of cellular therapies in the treatment of cancer.

Open studies in clinicaltrials.gov as of May 2017

| Open studies (n =) . | clinicaltrials.gov reference . |

|---|---|

| DLI | |

| Hematological malignancies (14) | NCT02673008, NCT01240525, NCT02458235, NCT02568241, NCT02328885, NCT02331706, NCT01839916, NCT02452697, NCT01982682, NCT03032783, NCT02566395, NCT01384513, NCT02566304, NCT02199041 |

| MDS/AML (7) | NCT02856464, NCT02472691, NCT02046122, NCT02684162, NCT01369368, NCT01758367, NCT02888522 |

| CLL (1) | NCT01849939 |

| Myeloma (2) | NCT01131169, NCT02700841 |

| CTL | |

| Hematological malignancies (2) | NCT02895412, NCT02203903 |

| EBV-associated malignancies (1) | NCT00002663 |

| CIK | |

| Leukemia/MDS (2) | NCT02752243, NCT01898793 |

| Lymphoma (2) | NCT02497898, NCT01799083 |

| MIL | |

| Myeloma (1) | NCT01858558 |

| CART | |

| CD5 directed (1) | NCT03081910 |

| CD19 directed (60) | NCT02935543, NCT02445222, NCT02547948, NCT03142646, NCT02799550, NCT02782351, NCT02813837, NCT03029338, NCT03121625, NCT03027739, NCT02640209, NCT03086954, NCT02822326, NCT02975687, NCT01864889, NCT02735291, NCT02728882, NCT02963038, NCT03101709, NCT02924753, NCT02247609, NCT03068416, NCT02810223, NCT02965092, NCT02186860, NCT02935257, NCT02842138, NCT03064269, NCT02537977, NCT02672501, NCT02624258, NCT02794246, NCT02652910, NCT03085173, NCT02443831, NCT02819583, NCT03110640, NCT03118180, NCT02685670, NCT02030834, NCT02349698, NCT02529813, NCT02081937, NCT02030847, NCT02028455, NCT02968472, NCT03016377, NCT02546739, NCT03050190, NCT02772198, NCT03103971, NCT02228096, NCT02851589, NCT02146924, NCT01853631, NCT02374333, NCT02659943, NCT01865617, NCT02445248, NCT02631044 |

| CD20 directed (3) | NCT02710149, NCT02965157, NCT01735604 |

| CD22 directed (4) | NCT02794961, NCT02935153, NCT02650414, NCT02721407 |

| CD30 directed (6) | NCT02259556, NCT02917083, NCT02958410, NCT02274584, NCT03049449, NCT02690545 |

| CD33 directed (4) | NCT01864902, NCT02799680, NCT02958397, NCT03126864 |

| CD123 directed (3) | NCT02937103, NCT03114670, NCT02159495 |

| CD133 directed (1) | NCT02541370 |

| CD138 directed (1) | NCT01886976 |

| BCMA directed (5) | NCT02954445, NCT02546167, NCT03070327, NCT03093168, NCT02215967 |

| LeY directed (1) | NCT02958384 |

| ROR1 (1) | NCT02706392 |

| Combination (4) | NCT02903810, NCT03125577, NCT03098355, NCT03097770 |

| Vaccines | |

| MDS/AML (8) | NCT01686334, NCT02493829, NCT03059485, NCT01734304, NCT02405338, NCT01773395, NCT03083054, NCT02498665 |

| CML (2) | NCT02543749, NCT00363649 |

| CLL (1) | NCT02802943 |

| Myeloma (1) | NCT02334865 |

| NHL (1) | NCT03035331 |

| NK cells | |

| Hematological malignancies (12) | NCT02280525, NCT02892695, NCT01619761, NCT01904136, NCT03056339, NCT02742727, NCT01823198, NCT00720785, NCT02727803, NCT01700946, NCT01807611, NCT02890758 |

| MDS/AML (14) | NCT01787474, NCT02809092, NCT02763475, NCT03081780, NCT02123836, NCT03050216, NCT02229266, NCT02944162, NCT02477787, NCT02782546, NCT01898793, NCT03068819, NCT02316964, NCT02781467 |

| ALL (2) | NCT02185781, NCT01974479 |

| Open studies (n =) . | clinicaltrials.gov reference . |

|---|---|

| DLI | |

| Hematological malignancies (14) | NCT02673008, NCT01240525, NCT02458235, NCT02568241, NCT02328885, NCT02331706, NCT01839916, NCT02452697, NCT01982682, NCT03032783, NCT02566395, NCT01384513, NCT02566304, NCT02199041 |

| MDS/AML (7) | NCT02856464, NCT02472691, NCT02046122, NCT02684162, NCT01369368, NCT01758367, NCT02888522 |

| CLL (1) | NCT01849939 |

| Myeloma (2) | NCT01131169, NCT02700841 |

| CTL | |

| Hematological malignancies (2) | NCT02895412, NCT02203903 |

| EBV-associated malignancies (1) | NCT00002663 |

| CIK | |

| Leukemia/MDS (2) | NCT02752243, NCT01898793 |

| Lymphoma (2) | NCT02497898, NCT01799083 |

| MIL | |

| Myeloma (1) | NCT01858558 |

| CART | |

| CD5 directed (1) | NCT03081910 |

| CD19 directed (60) | NCT02935543, NCT02445222, NCT02547948, NCT03142646, NCT02799550, NCT02782351, NCT02813837, NCT03029338, NCT03121625, NCT03027739, NCT02640209, NCT03086954, NCT02822326, NCT02975687, NCT01864889, NCT02735291, NCT02728882, NCT02963038, NCT03101709, NCT02924753, NCT02247609, NCT03068416, NCT02810223, NCT02965092, NCT02186860, NCT02935257, NCT02842138, NCT03064269, NCT02537977, NCT02672501, NCT02624258, NCT02794246, NCT02652910, NCT03085173, NCT02443831, NCT02819583, NCT03110640, NCT03118180, NCT02685670, NCT02030834, NCT02349698, NCT02529813, NCT02081937, NCT02030847, NCT02028455, NCT02968472, NCT03016377, NCT02546739, NCT03050190, NCT02772198, NCT03103971, NCT02228096, NCT02851589, NCT02146924, NCT01853631, NCT02374333, NCT02659943, NCT01865617, NCT02445248, NCT02631044 |

| CD20 directed (3) | NCT02710149, NCT02965157, NCT01735604 |

| CD22 directed (4) | NCT02794961, NCT02935153, NCT02650414, NCT02721407 |

| CD30 directed (6) | NCT02259556, NCT02917083, NCT02958410, NCT02274584, NCT03049449, NCT02690545 |

| CD33 directed (4) | NCT01864902, NCT02799680, NCT02958397, NCT03126864 |

| CD123 directed (3) | NCT02937103, NCT03114670, NCT02159495 |

| CD133 directed (1) | NCT02541370 |

| CD138 directed (1) | NCT01886976 |

| BCMA directed (5) | NCT02954445, NCT02546167, NCT03070327, NCT03093168, NCT02215967 |

| LeY directed (1) | NCT02958384 |

| ROR1 (1) | NCT02706392 |

| Combination (4) | NCT02903810, NCT03125577, NCT03098355, NCT03097770 |

| Vaccines | |

| MDS/AML (8) | NCT01686334, NCT02493829, NCT03059485, NCT01734304, NCT02405338, NCT01773395, NCT03083054, NCT02498665 |

| CML (2) | NCT02543749, NCT00363649 |

| CLL (1) | NCT02802943 |

| Myeloma (1) | NCT02334865 |

| NHL (1) | NCT03035331 |

| NK cells | |

| Hematological malignancies (12) | NCT02280525, NCT02892695, NCT01619761, NCT01904136, NCT03056339, NCT02742727, NCT01823198, NCT00720785, NCT02727803, NCT01700946, NCT01807611, NCT02890758 |

| MDS/AML (14) | NCT01787474, NCT02809092, NCT02763475, NCT03081780, NCT02123836, NCT03050216, NCT02229266, NCT02944162, NCT02477787, NCT02782546, NCT01898793, NCT03068819, NCT02316964, NCT02781467 |

| ALL (2) | NCT02185781, NCT01974479 |

CIK, cytokine-induced killer; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MIL, marrow-infiltrating lymphocyte; NK, natural killer; ROR1, receptor tyrosine kinase like orphan receptor 1. Other abbreviations are explained in Table 1.

Correspondence

Alan S. Wayne, Children's Center for Cancer and Blood Diseases, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Mailstop #54, Los Angeles, CA 90027; e-mail: awayne@chla.usc.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.S.W. has received research funding from MedImmune, Kite Pharma, and Spectrum Pharmaceuticals and has served on an advisory committee for Servier. He also is the co-inventor of investigational products with patents assigned to the National Institutes of Health. A.C.D. declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

![Figure 2. Theoretical relative therapeutic potential of cellular therapies for relapse. The shaded quadrant represents the zone of optimal specificity with respect to tumor vs off-target cytotoxic tissue damage, which maximizes antitumor potency and minimizes cell-mediated morbidity. Conventional DLI and second SCT (depicted in red) are the currently available cell-based treatments for relapse, against which novel therapies (blue) will be judged. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CIK, cytokine-induced killer; DLI, donor lymphocyte infusion; MiAg, minor histocompatibility; NK, natural killer; SCT, stem cell transplantation; TAA, tumor-associated antigen. Reprinted from de Lima et al5 with permission (published under the terms of the Creative Commons attribution–noncommercial–no derivatives license [CC BY NC ND]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/hematology/2017/1/10.1182_asheducation-2017.1.708/4/m_hem00096f2.jpeg?Expires=1769226901&Signature=3r-kiag8eVsAZwitlAHzkn4oYmXG6w3MUKoE-5isLVIoAZjjJ6RpDV6eAb7I2Dl8QyP1gf4pfwh58kac6bmPFaVJSPLcBQwsP39OWBX6Q83e2M1WtGLqR3ZCn625RAhkkq33OgxYy7IilMHnOJMFtE8-D7zIYrRJxYfn-a0OSUogA5uLBJqgwuolY7L0B~I5B3apB79i93hWHAGi5yOjUbPubE5HnYGhWIxtdIx1qeapmavrYs0ALBsuOsv7g95OzjtCBZohfa2BI~8zJjhToOdEkA~f~8pI-ORU8lZIuXc2TjvqY72bPBQoiKcyCU5gaYTeBcEIxvdRYMpA136Hvw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)