Abstract

Chronic pain affects one-half of adults with sickle cell disease (SCD). Despite the prevalence of chronic pain, few studies have been performed to determine the best practices for this patient population. Although the pathophysiology of chronic pain in SCD may be different from other chronic pain syndromes, many of the guidelines outlined in the pain literature and elsewhere are applicable; some were consensus-adopted in the 2014 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute SCD Guidelines. Recommended practices, such as controlled substance agreements and monitoring of urine, may seem unnecessary or counterproductive to hematologists. After all, SCD is a severe pain disorder with a clear indication for opioids, and mistrust is already a major issue. The problem, however, is not with a particular disease but with the medicines, leading many US states to pass broad legislation in attempts to curb opioid misuse. These regulations and other key tenets of chronic pain management are not meant to deprive adults with SCD of appropriate therapies, and their implementation into hematology clinics should not affect patient-provider relationships. They simply encourage prudent prescribing practices and discourage misuse, and should be seen as an opportunity to more effectively manage our patient’s pain in the safest manner possible. In line with guideline recommendations as well as newer legislation, we present five lessons learned. These lessons form the basis for our model to manage chronic pain in adults with SCD.

Learning Objectives

To outline an approach to manage highly utilizing adults with sickle cell disease

To describe how opioid guidelines can be incorporated into a management plan for adults with sickle cell disease

Introduction

Pain is the most common complication seen in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).1 It often begins in infancy after the β-globin gene switch, when levels of fetal hemoglobin drop as levels of sickle hemoglobin rise. That sickle hemoglobin, in the deoxy-sickle state, has the potential to aggregate into fibers, promoting a shape change in the red cell that gives rise to sickle-shaped erythrocytes. Rigid and adhesive, these sickle-shaped erythrocytes are prone to occlude the microvasculature, especially within the bones, where tissue ischemia and injury lead to pain. These are typically self-limited episodes of pain, especially in children, and follow a crescendo-decrescendo course that lasts about 10 days.2 During this time, the child’s pain is usually managed with oral or intravenous opioids, and after the episode resolves, the child is typically pain-free and may go months or years without another episode of pain.1

This intermittent pain phenotype is different from the chronic pain syndrome that develops in many adults. On the background of ongoing vasoocclusion, their chronic pain syndrome follows an exacerbating/remitting course with periods of high and low pain. Descriptions of this pain phenotype come from the Pain in Sickle Cell Epidemiology Study, which established that 50% of adults report pain on ≥3 d/wk, 30% report pain daily, and 40% take opioids daily.3,4 Although it is logical to assume that the pain is secondary to avascular necrosis, leg ulcers, or other sequelae from vasoocclusion, there is often no anatomic correlate to explain the pain, which can be confusing to providers.5 This well-described phenomenon suggests a different mechanism of pain in adults with SCD, one that is more complicated than vasoocclusion alone. Although the pathophysiology is still being elucidated, what we do know is that frequent pain, nerve damage, chronic inflammation, and in some cases, opioid use can promote central sensitization of the pain that can contribute to a chronic pain phenotype.6 Consistent with this pathogenesis, adults frequently exhibit allodynia and hyperalgesia.7,8 Highly sensitive to pain, adults with these features may report exacerbations (or “crises”) monthly, weekly, or even daily (a “crisis” is less of a diagnosis than a symptom of severe pain).9 Not surprisingly, adults with chronic pain can generate a high number of admissions to the emergency department (ED) and hospital.9

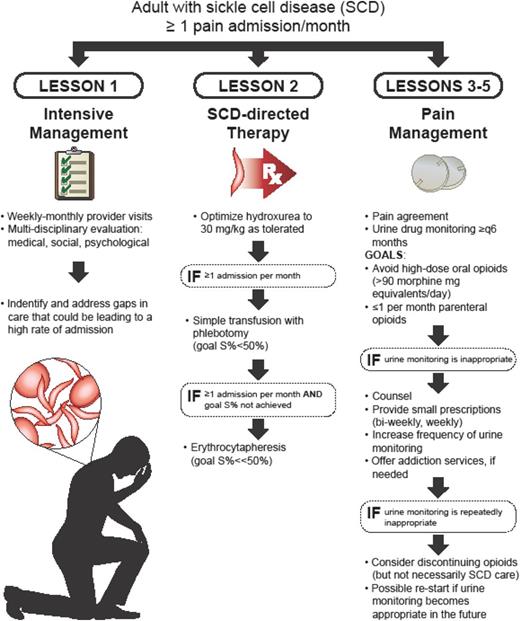

The result is that, day in and day out, hematologists are called on to manage acute and chronic pain in adults with SCD, a job that they may not be comfortable with or appropriately trained to do. Many adults with SCD do not fit into the clinical paradigm of episodic vasoocclusion that they learned about in fellowship. What is more, their training in pain management was likely in the setting of acute pain, which is different than chronic. Unfortunately, the literature does not provide much guidance either, because there are few high-quality studies about chronic pain management in adults with SCD.10 To top it off, we are currently in the midst of what has been called an “opioid epidemic.” Buoyed by concerns that pain was undertreated,11 opioid prescriptions rose sharply in the United States from the 1990s to 2010.12 Opioid misuse and its associated mortality have led nearly every state to pass legislation to restrict opioid prescribing.12,13 These regulations, although necessary, may require a different clinical model than most hematologists currently have. All of these factors (a poorly understood pathophysiology, a paucity of training, an absence of high-quality evidence, increased regulations and scrutiny surrounding opioids) create a difficult climate for hematologists to manage the pain of adults with SCD. What we are left with is expert opinion in the form of guidelines, such as those from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)14 (Table 1) and the American Association of Pain Medicine/American Pain Society15 (some of which were adopted in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI] 2014 SCD guidelines10 ), that can be implemented in a model for chronic pain management for adults with SCD. Although there are nuances to the care of adults with SCD—a fact that is recognized in the CDC guidelines, wherein readers are referred to the NHLBI’s guidelines “given the challenges of managing the painful complications of SCD”14 —many of the basic principles of pain management still apply. Given the paucity of data in management of chronic pain in patients with SCD, much of what we present here is expert opinion, similar to “How I Treat.” We will discuss five lessons learned in the context of a representative clinical case, which helped us formulate a model of care (Figure 1).

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioid for Chronic Pain, 2016: 12 recommendations (abbreviated)

| 1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain |

| 2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should establish treatment goals with all patients |

| 3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy |

| 4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should prescribe immediate release opioids instead of long-acting opioids |

| 5. When opioids are started, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose (use caution when increasing above 50 morphine milligram equivalents and avoid increasing to 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater) |

| 6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain; when used for acute pain, prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate release opioids, and prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration (typically ≤7 d) |

| 7. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 wk of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation (then see at least every 3 mo) |

| 8. Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid therapy, clinicians should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms |

| 9. Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program data |

| 10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider repeating at least annually |

| 11. Clinicians should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible |

| 12. Clinicians should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment of patients with opioid use disorder |

| 1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain |

| 2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should establish treatment goals with all patients |

| 3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy |

| 4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should prescribe immediate release opioids instead of long-acting opioids |

| 5. When opioids are started, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose (use caution when increasing above 50 morphine milligram equivalents and avoid increasing to 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater) |

| 6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain; when used for acute pain, prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate release opioids, and prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration (typically ≤7 d) |

| 7. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 wk of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation (then see at least every 3 mo) |

| 8. Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid therapy, clinicians should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms |

| 9. Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program data |

| 10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider repeating at least annually |

| 11. Clinicians should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible |

| 12. Clinicians should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment of patients with opioid use disorder |

Lessons learned

Case

L.J. is a 21-year-old man with a history of hemoglobin SS disease who was previously seen in a pediatric SCD clinic. He reports a throbbing pain in the legs and arms that occurs on a nearly daily basis. Over the past 12 months, he has been treated with parenteral hydromorphone for pain 22 times in the ED. After one of these admissions, he was prescribed oxycodone 5 mg.

Lesson 1: Focus resources on adults with high rates of utilization for pain

A small subset of adults with SCD accounts for a disproportionate number of admissions (Figure 1).16,17 At our institution, ∼10% of adults with SCD generate 50% of the SCD admissions, figures that are consistent with national averages.16 Although a reasonable assumption is that this 10% represents those in the SCD population with the most end-organ dysfunction, this is often not the case.16,18 In our population, highly utilizing adults had a similar prevalence of SCD complications to others in the clinic: many had hemoglobin SC or hemoglobin sickle β-plus thalassemia and on average, were younger (the transition period can be particularly challenging).16 The only universal feature that we identified among our highly utilizing adults was chronic pain16 ; however, we found a myriad of factors that were likely contributing to the high rate of admission: mental illness, social dysfunction, addictive disorder.19 The chief complaint for these admissions may be pain, but any of these factors can affect the chronic pain phenotype: it is not a one size fits all problem.

Our approach with highly utilizing adults is to intensely manage them with frequent provider visits (monthly, biweekly, or weekly visits) to build trust, identify key drivers of the admission rate (medical, social, psychological gaps), and rapidly implement plans of care. It is a multidisciplinary approach, in which we implement aggressive SCD treatment and address social and psychological gaps, all of the while being mindful of oral opioid doses and the use of parenteral opioids (see subsequent lessons). At our institution, this model resulted in a reduction of admissions and 30-day readmissions as well as opioid use.16,19 Limitations include the required staffing and burnout. Frequent visits with adults who are chronically in pain and consistently in the hospital can be frustrating. What is worse, as soon as one patient’s rate of utilization improves, another’s may worsen, which means the clinic must be ever-vigilant.16,18

Recommendation 1: L.J. needs to be seen often and thoroughly examined for medical, social, and psychological contributors to pain.

Lesson 2: Aggressively treat any underlying causes of pain, including SCD

Chronic pain management with opioids is best done in conjunction with aggressive SCD management (Figure 1). That means fix what is fixable (avascular necrosis) and prevent vasoocclusive pain episodes. When adults have a chronic pain syndrome, they are typically more sensitive to pain.5,20 Levels of vasoocclusion that may have been subclinical as a child may cause pain as an adult, which is likely why exacerbations of pain occur as frequently as they do in adults. Step 1 is to optimize hydroxyurea (titrate to 30 mg/kg as tolerated), consistent with NHLBI guidelines.10 If that fails, a chronic transfusion regimen, with monthly transfusions similar to secondary stroke prophylaxis, should be considered. Although the data for prevention of acute and chronic pain with transfusions are not as strong as they are for secondary stroke prophylaxis, there are data from secondary analyses of randomized trials.21,22 After weighing the benefits of transfusion against the risks of iron overload and alloimmunization, our practice is to start with a course of simple transfusions with phlebotomy for 6 to 12 months. Our goal is to maintain hemoglobin S percentage <50%. If iron overload is an issue or if hemoglobin S% targets are not being met, erythrocytapheresis can be initiated. Of note, our experience is that chronic pain improves with aggressive transfusion but does not stop completely. Adults with exceedingly low percentages of sickle hemoglobin often have persistent chronic pain at some level. Potentially, another option is consideration for a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Even after a successful transplant, it may take months for pain to diminish.23

Recommendation 2: Hydroxyurea should be initiated and titrated for L.J. If utilization does not improve after a 6-month course of hydroxyurea, chronic transfusions should be considered.

Lesson 3: Apply principles of chronic pain management to a clinic model

Opioids are an appropriate therapy for acute and chronic pain in adults with SCD, so why implement chronic pain management practices that are meant to prevent opioid misuse, especially when issues of trust may be problematic (Figure 1)? Because pain was reportedly being undertreated, opioid prescriptions soared in the United States over the past ≥20 years.12 Not immune to this trend, the percentage of SCD patients treated with opioids in the United States likely far exceeds that of other countries.24-26 In response to these prescribing practices and the surge in opioid-related deaths, nearly every state has put forth legislation and/or recommendations intended to curb opioid misuse.12 Many of these suggest or mandate the use of controlled substance agreements, urine monitoring, and prescription drug monitoring programs,12,14 consistent with CDC recommendations.14 They also warn against the concomitant use of opioids and benzodiazepines.14 Without question, prescribers of opioids are under increased scrutiny, and hematologists are not excused from the new regulations. Although SCD-associated pain is a legitimate indication for opioids, the benefit of long-term opioids for chronic pain is not known (there has never been a study of opioid for chronic pain, SCD or otherwise, >1 year in duration),27 and risks of opioids are real, including overdose and misuse.12,27 Although the prevalence of opioid misuse is not higher in adults with SCD compared with other pain disorders, the reality is that a small subset of adults with SCD will misuse their medicines and may suffer from an opioid use disorder.28,29 This is true of every chronic pain condition, even cancer.30 A bigger question is what to do when controlled substance agreements are violated and/or urine monitoring is inappropriate. Our practice is to use an algorithmic approach that counsels the patient and provides opioids in smaller quantities with more frequent urine monitoring. If there is concern for an opioid use disorder, treatment programs are recommended. If violations persist, however, opioids prescriptions may have to be stopped. Here is where the distinction between provision of care and provision of opioids is critical: if opioids prescriptions are stopped, that does not mean that other care (hydroxyurea, blood transfusions) has to be stopped as well.

Recommendation 3: After a discussion about provider-patient responsibilities surrounding opioids, L.J. should sign a controlled substance agreement and provide a sample for urine monitoring.

Lesson 4: Higher doses and larger quantities of oral opioids often do not help

In years past, a tenet of pain management was that there was no ceiling to the analgesic effect of opioids (Figure 1).31 That meant that, if pain was not controlled, higher doses might be beneficial. In actuality, high-dose opioids (typically defined as >90 mg of morphine milligram equivalents per day) are associated with significant risks: osteopenia, hormonal imbalance, immune dysfunction, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, respiratory depression, and death.31-34 What is more, in the pain literature, there is little evidence that high-dose opioids improve pain or function but plenty of evidence that they cause harm.14,27 Adults with SCD are known to use higher doses of opioids than other chronic pain populations35,36 ; however, there are no studies to determine whether these high doses provide benefit. For hematologists providing care for adults with SCD, the challenge is that each exacerbation of pain can theoretically be seen as a failure of pain management. Over time, this can lead to “creep” in either doses or amount of opioids. In addition to placing the patient at an increased risk of death from overdose, these higher doses can promote opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which could actually worsen the pain syndrome.32 Our practice, which is in line with current CDC guidelines, is to rely more on short- than long-acting opioids for pain management14 : not only because long-acting opioids are associated with greater risks than short-acting14,37 but because chronic pain in adults follows an exacerbating/remitting course, with large fluctuations in daily pain, and long-acting opioids (especially in high doses) could necessitate that the patient take the dose on “good” days simply to prevent withdrawal. If long-acting opioids are used, cognizance of the dose is critical; if severe pain requires that doses be increased, frequent reassessments of the effects of therapy on the patient’s functional status should be performed to determine if doses could be lowered in the future. Also, use nonpharmacologic therapies and nonopioid pharmacological therapies: acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and neuropathic agents.14 Neuropathic pain does occur in patients with SCD, and our experience is that neuropathic agents work well in patients with neuropathic descriptors.8,38

Recommendation: Despite frequent admissions, avoid significant increases in L.J.’s dose and amount of short-acting opioid or the addition of a high-dose, long-acting opioid.

Lesson 5: Parenteral opioids are not the optimal treatment of chronic pain

The 2014 NHLBI guidelines devote considerable space (and appropriately so) to the management of acute pain episodes to ensure that patients are rapidly assessed and that pain is managed in a timely fashion (Figure 1).10 For acute episodes of pain, prompt administration of parenteral opioids is appropriate. What happens, however, when an adult presents to the ED with increased pain on a weekly basis? Consistent with other chronic pain conditions, vital signs and laboratory values are stable. Is it appropriate to treat this adult with parenteral opioids every week? There is no perfect answer to this question. The distinction between acute and chronic pain can be difficult in an adult with SCD, whose pain may be acutely increased above their baseline but whose phenotype follows a chronic, exacerbating/remitting pattern. Our stance is that infrequent use of parenteral opioids is appropriate (less than or equal to once per month); however, if exacerbations of pain are more frequent, consistent with a chronic pain phenotype, management with parenteral opioids is typically not a good strategy. In fact, it may be doing the patient a significant disservice by exposing them to the risks of potent and often high-dose opioids. A better approach is to marshal the clinic’s resources to determine why the patient is presenting to the ED so frequently and then address identified gaps in care. To avoid overuse of parenteral opioids, communication with ED providers is critical. Because the ED is fast-paced, with lots of ill patients, many providers will not stop to ask why a patient like L.J. is presenting several times per month. The easiest course is to treat L.J. with a few doses of parenteral opioids and then discharge him. In cases like L.J.’s, plans of care created by providers with long-term relationships with the patient can be extremely helpful to make ED providers aware that L.J. has a chronic pain syndrome and that frequent parenteral opioids may not optimal. Our practice is to post detailed plans of care with treatment recommendations in the electronic medical record for highly utilizing patients that encourage treatment with oral opioids and nonopioid pharmacologics.19

Day hospitals are another setting where parenteral opioids can become an issue. If SCD providers are not cognizant of how often patients are being treated, parenteral opioids can be used to treat chronic pain. In fact, for all of their benefits, day hospitals have been shown to increase the per-patient receipt of parenteral opioids.39 This may be especially problematic for the adult whose chronic pain syndrome is severe.39 Our approach is to use a standardized phone triage system that addresses the patient’s chief complaint and any accompanying symptoms along with the measures that they have taken at home to manage those symptoms (oral opioids, nonopioid pharmacological therapy). If the chief complaint is pain, we require that patient’s pain is refractory to oral opioids before presentation. (An exception would be a patient with rare pain who may not use oral pain medicine.) Beyond that, we make it clear to the patient that, on presentation, an assessment will occur. A treatment plan will then be formulated based on that assessment, which may or may not include parenteral opioids. In general, we aim to minimize the use of parenteral opioids in the day hospital to once per month.

Recommendation: Given L.J.’s frequent admissions, formulate a plan of care for the ED that encourages the use of nonopioid analgesics and oral opioids to manage his pain.

Summary

L.J.’s case is not uncommon. Adults with SCD have a devastating disease that can be associated with a severe, chronic pain syndrome.3 It often begins in adolescence and does not follow the typical on/off pattern that characterize the acute episodes of childhood. Instead, many adults suffer from an exacerbating/remitting pain syndrome that is chronic and frequently not accompanied by the objective changes in vitals, laboratory tests, or imaging that providers expect. What adds to the confusion is the paucity of data available to guide these providers in the treatment this chronic pain syndrome. Therapies, such as hydroxyurea and transfusion, were not examined in the context of chronic pain. Opioids, a mainstay of pain management, have unique challenges in this population of patients who, unlike a patient being palliated for cancer pain, may require treatment of decades. The lessons presented here were borne from our experience of starting a program for adults with SCD; they helped us develop our model of care, which we present here in a “How I Treat” format. Without strong data in SCD patients to rely on, it is largely based on studies of other populations and society’s guidelines, notably those from the pain literature and the CDC.14,15 The pathophysiology of other pain states may be different; however, the principles of pain management still apply, and often, because there are too few dedicated SCD providers, pain specialists are called on to manage patients with SCD. In cases in which there is no hematologist or the hematologist does not have the training or infrastructure to manage chronic pain, pain specialists could be an effective alternative to manage this issue in adults with SCD. For certain, opioids are indicated for the management of SCD-associated pain, but that does not excuse hematologists from newer legislation that aims to curb opioid misuse or the prudent pain management practices that arise from them: they are in the best interest of the patient.

Correspondence

Joshua J. Field, Blood Center of Wisconsin, 8733 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: joshua.field@bcw.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding and honoraria from Incyte, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, and NKT Therapeutics.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.