Abstract

Treatment options for mantle cell lymphomas have expanded considerably over recent years, offering hematologists solutions for older patients with an appropriate risk-to-benefit ratio. Indeed, unfit older patients are exposed to a higher risk of toxicity with a standard treatment. Although new treatments have generally good safety profiles, they may lead to unexpected consequences in unfit older patients. Involving geriatricians and a comprehensive geriatric assessment in patient care could help hematologists address these vulnerabilities. The geriatric evaluation process is time-consuming but can be simplified, and its potential to help hematologists foresee unexpected consequences of treatment has now been demonstrated.

Learning Objectives

To recognize patients’ vulnerabilities that influence treatment tolerance and outcome

To better design objectives and manage treatment toxicities in mantle cell lymphoma

Standard treatment relates to disease, not to patients. The key in older patients is to adapt the standard treatment to the specific situation of the patient through a strict evaluation of risks and benefits because higher risks may consume benefits.

Recent population-based series comprising 1771 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients revealed a median age of over 70 years at diagnosis.1-3 Indeed, because of various comorbidities and frailties, treatment decision-making in older patients will be more complex due to an increased risk of toxicity that may lead to further unexpected consequences. This was not a major issue when treatment possibilities were limited. However, with current treatment strategies that may be feasible in the elderly, undertreating older MCL patients may deprive them of a chance of cure. Yet, caution should be advised in unfit patients because some toxicities, well tolerated in younger patients, may have important consequences in older subjects with an impaired condition unrelated to lymphoma. Consequently, potential toxicities should be anticipated and assessed against the geriatric impairments observed in each patient before any decision is made.

An obvious approach in vulnerable and frail patients with lymphoma is to propose either standard treatment dose reductions or less toxic combinations, although, too often, not only risks but also benefits are reduced. Another alternative is to replace potentially toxic drugs by new, less toxic compounds, mainly targeted therapies, to maintain benefits while decreasing risks. These 2 possibilities are available to treat MCL patients.

The experience of geriatricians can be of major help in making the right choice in this context. A comprehensive geriatric assessment has the capacity to diagnose vulnerabilities in major geriatric domains such as dependence, nutrition, cognition, mood, and falls. The conclusions of a geriatrician will allow oncohematologists to decide how to adapt the standard treatment to make it as secure as possible. However, the introduction of this new medical competence in the oncohematological daily practice is not straightforward. Decisions cannot be based on thresholds of the score of various questionnaires. Instead, they should implement the interpretation of the results by an experienced geriatrician, the so-called comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), a long, time-consuming, process. Consequently, many teams cannot afford this pretreatment evaluation. A potential solution is to use a screening questionnaire that allows restricting the complete procedure only to patients who may need it. This approach is now reaching consensus in the geriatric oncology community.4,5

Geriatric assessment allows identifying patients at risk of adverse outcomes under treatment

The major objective is to identify, among the available baseline data, a limited number of factors that will allow classifying patients into risk groups in order to determine the appropriate treatment strategy, that is, full-dose standard treatment in fit patients to achieve complete remission, adapted standard treatment in vulnerable subjects to control disease, or tailored treatment in frail ones to palliate symptoms and preserve quality of life. Treatment decision will depend on life expectancy (without lymphoma), MCL prognostic factors, the observed geriatric impairments (too often limited to performance status), and the risk of early events (such as death, toxicity, or functional decline).

The classification of patients according to either the physician’s judgment or the geriatric assessment results, although highly correlated, shows different results with a major underestimation of the frail population by the physician. This was shown in a prospective series of 200 patients,6 in which the proportions of fit, vulnerable, and frail patients were, respectively, 64.3%, 32.4%, and 3.2% by the physician’s judgment and 25%, 25.5%, and 49.5% according to Balducci and Extermann’s classification.7 This was confirmed by recent data which suggest that the geriatric approach is more valid to identify palliative patients who will not benefit from standard therapy.8,9 Although performed in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (173 consecutive, previously untreated patients), these results can be extrapolated to MCL. Patients were classified as fit or unfit either by hematologists, according to standard criteria, or by geriatricians, according to 4 criteria: age, activities of daily living (ADL), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRS-G), and occurrence of geriatric syndromes.9 Geriatric results were blinded to the hematologists. Again, the proportion of unfit patients was different: 36% for physicians and 54% according to geriatric classification. Geriatric criteria appeared more efficient to predict prognosis because patients classified as fit by the physician, and treated accordingly, but frail with geriatric assessment, behaved as patients classified as unfit by the 2 methods in terms of survival.

In a search for tools that may efficiently help hematologists classify patients in terms of risks, data from the whole geriatric oncology field should be considered. Some authors searched for factors to predict life expectancy at various time points in the general population.10-12 Based on large series of patients, including validation cohorts, these factors are robust and efficiently discriminate populations with different life expectancy. In all of them, cancer is one of the risk factors. Scores of Lee10 and Schonberg11 are currently studied in the field of oncology to determine whether they can help in the treatment decision process.

In older patients, the main goal is most often to control disease without severe adverse events while keeping the patient at home. Consequently, occurrence of early death, severe toxicity, and functional decline during therapy suggest that the risks of the treatment were underestimated. Predictors of these 3 events may help hematologists take appropriate treatment decisions. In a series of 364 patients with various types of cancer including one-third of lymphomas, the risk of early death (within 6 months of treatment initiation) was predicted by disease extension, sex, the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), and Timed Up and Go (TUG) tests.13 Two major series targeted high-grade toxicity. Hurria et al selected grade 3 to 5 toxicities as end points in a large series of 500 patients.14 Various factors were identified including age, biological data (creatinine clearance and hemoglobin level), chemotherapy features (dose intensity, number of drugs), and geriatric status (hearing, falls, medications, walking, and social activities). Depending on the risk score, grade 3 to 5 toxicity rate varied from 25% to 89%. Of note, performance status was not predictive of toxicity risk. Extermann et al analyzed separately grade 4 hematological and grade 3 to 4 nonhematological toxicities in a series of 518 evaluable patients.15 Factors such as age, diastolic blood pressure, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase level, and chemotherapy toxicity score were predictive together with instrumental ADL (IADL), Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and MNA. The final risk score predicted a hematological toxicity risk from 7% to 100% and a nonhematological toxicity rate from 33% to 93%. Toxicity can also be considered through different end points such as unplanned hospitalization or functional decline during treatment. In a series of patients older than 70 years of age with various kinds of cancer before chemotherapy, including a third of lymphomas, we defined severe toxicity as unplanned hospitalization during treatment.16 Forty-seven patients experienced unexpected hospital admission. Patients with low platelet count and low MNA score had a significantly higher risk for treatment-related hospitalization (odds ratios, 3.763 and 4.194, respectively). Adaptation of chemotherapy schedule and doses by the investigator significantly reduced the risk of hospital admission (odds ratio, 0.509). In the same series of patients, we searched for factors predictive of functional decline (defined as a decrease of 0.5 points or more on the ADL scale between baseline and the second cycle of chemotherapy).17 With 50 patients experiencing functional decline among 299 evaluable patients, high baseline Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and low IADL were independently associated with an increased risk of functional decline.

Overall, data gathered from the literature demonstrate that geriatric assessment adds to other classical factors to predict early death or survival, toxicity (whatever the definition), or functional decline. All dimensions of geriatric assessment appear to have prognostic value although some domains may prevail. Consequently, baseline geriatric evaluation may help physicians to better anticipate potential adverse events that may occur during treatment and thus help make the right decision about treatment intensity and possible interventions. Yet, CGA cannot be offered to all elderly cancer patients because it is time-consuming for physicians and nurses. It makes it unaffordable for community hospitals and small cancer hospitals. This has made the development of shortened instruments essential.4,18 To be acceptable for the whole community, such instruments should be performed shortly (<10 minutes) by a nurse or physician trained for the tool completion but not necessarily in geriatrics. A few instruments have been identified. The ONCODAGE study evaluated 2 screening questionnaires, G8 (Table 1) and the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES13; Figure 1),19 and included 1688 patients; 1435 were eligible and evaluable. Geriatric assessments included CIRS-G, ADL, IADL, MMSE, GDS15, MNA, and TUG. For VES13, sensitivity and specificity were 68.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 66.0%; 71.4%) and 74.3% (95% CI, 68.8%; 69.3%), respectively. For G8, sensitivity was higher at 76.5% (95% CI, 73.9%-78.9%) and specificity lower at 64.4% (95% CI, 58.6%-70.0%). The time required to complete the G8 questionnaire was, on average, 4.4 minutes (±2.8) and 98.7% completed it in <10 minutes. Multivariate analysis showed that, together with sex, stage, and performance status, G8 was also predictive of 1-year survival. Another study including 937 prospective patients with various types of cancer, including hematological malignancies, showed 86.5% sensitivity and 59.3% specificity and confirmed the strong prognostic value of the G8 questionnaire.20 The Flemish version of the Triage Risk Screening Tool (fTRST) (Table 2) was also proposed and validated for screening. Sensitivity was 91.3% and specificity was 41.9% with a threshold for abnormality defined as ≥1. A recent systematic review5 identified 17 different screening tools and showed that G8 and fTRST were the most sensitive ones and that G8 appears to be the most robust.

The G8 questionnaire

| Items . | Possible answers (score) . |

|---|---|

| Has food intake declined over the past 3 mo due to loss of appetite, digestive problems, chewing or swallowing difficulties? | 0: Severe decrease in food intake |

| 1: Moderate decrease in food intake | |

| 2: No decrease in food intake | |

| Weight loss during the last 3 mo | 0: Weight loss >3 kg |

| 1: Does not know | |

| 2: Weight loss between 1 and 3 kg | |

| 3: No weight loss | |

| Mobility | 0: Bed or chair bound |

| 1: Able to get out of bed/ chair but does not go out | |

| 2: Goes out | |

| Neuropsychological problems | 0: Severe dementia or depression |

| 1: Mild dementia or depression | |

| 2: No psychological problems | |

| BMI (weight in kg)/(height in m2) | 0: BMI <19 |

| 1: BMI = 19 to BMI <21 | |

| 2: BMI = 21 to BMI <23 | |

| 3: BMI = 23 and >23 | |

| Takes more than 3 medications per day | 0: Yes |

| 1: No | |

| In comparison with other people of the same age, how does the patient consider his/her health status? | 0: Not as good |

| 0.5: Does not know | |

| 1: As good | |

| 2: Better | |

| Age | 0: >85 |

| 1: 80-85 | |

| 2: <80 | |

| Total score | 0-17 |

| Items . | Possible answers (score) . |

|---|---|

| Has food intake declined over the past 3 mo due to loss of appetite, digestive problems, chewing or swallowing difficulties? | 0: Severe decrease in food intake |

| 1: Moderate decrease in food intake | |

| 2: No decrease in food intake | |

| Weight loss during the last 3 mo | 0: Weight loss >3 kg |

| 1: Does not know | |

| 2: Weight loss between 1 and 3 kg | |

| 3: No weight loss | |

| Mobility | 0: Bed or chair bound |

| 1: Able to get out of bed/ chair but does not go out | |

| 2: Goes out | |

| Neuropsychological problems | 0: Severe dementia or depression |

| 1: Mild dementia or depression | |

| 2: No psychological problems | |

| BMI (weight in kg)/(height in m2) | 0: BMI <19 |

| 1: BMI = 19 to BMI <21 | |

| 2: BMI = 21 to BMI <23 | |

| 3: BMI = 23 and >23 | |

| Takes more than 3 medications per day | 0: Yes |

| 1: No | |

| In comparison with other people of the same age, how does the patient consider his/her health status? | 0: Not as good |

| 0.5: Does not know | |

| 1: As good | |

| 2: Better | |

| Age | 0: >85 |

| 1: 80-85 | |

| 2: <80 | |

| Total score | 0-17 |

Bellera et al.45

BMI, body mass index.

fTRST score

| Item . | Score . | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes . | No . | |

| Presence of cognitive impairment (disorientation, diagnosis of dementia, or delirium) | 2 | 0 |

| Lives alone or no caregiver available, willing, or able | 1 | 0 |

| Difficulty with walking or transfers or fall(s) in the past 6 mo | 1 | 0 |

| Hospitalized in the last 3 mo | 1 | 0 |

| Polypharmacy: ≥5 medications | 1 | 0 |

| Item . | Score . | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes . | No . | |

| Presence of cognitive impairment (disorientation, diagnosis of dementia, or delirium) | 2 | 0 |

| Lives alone or no caregiver available, willing, or able | 1 | 0 |

| Difficulty with walking or transfers or fall(s) in the past 6 mo | 1 | 0 |

| Hospitalized in the last 3 mo | 1 | 0 |

| Polypharmacy: ≥5 medications | 1 | 0 |

Once screened as unfit, patients deserve further attention from their hematologist and CGA is the most obvious solution. However, it may not be possible to implement this geriatric assessment in all cancer centers depending on the availability of geriatricians. Consequently, other solutions should be considered, including increased medical attention from the hematologist such as a thorough evaluation of comorbidities; a precise evaluation of major functions such as renal and hepatic systems; and consideration of nutritional, socioeconomic, mood, and cognitive conditions of the patients through evaluation by supportive care professionals. Yet, the obvious proposal is a 2-step process including a screening examination performed in the hematology setting, probably G8 or fTRST, followed by a second step performed by geriatric teams, ideally CGA. Geriatricians will designate the necessary evaluation tools depending on the information required by the hematologist: feasibility of treatment or specific search on some domains which may be impaired by treatment toxicity. From the literature above, some tools should probably be part of this evaluation including certainly ADL and IADL, but also MNA, TUG, and MMSE.13-17 A shortened version of CGA should be developed and is the subject of current research.

Which are the current treatment options in unfit older patients with MCL

Before any treatment, a diagnostic process and a pretreatment workup should be standard. Diagnosis should be ensured through cyclin D1 overexpression or t(11;14)(q13;q32) diagnosis. Pretreatment workup should include a computed tomography scan, a bone marrow biopsy or an aspirate, and Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) evaluation21 (or 1 of the 2 scores including the Ki67 Proliferative Index [combined MIPI (MIPIc)22 or GOELAMS Index23 ]), and optionally positron emission tomography–computed tomography in fit patients. Bone marrow biopsy may be omitted in frail subjects or replaced by an aspirate. As outlined in the previous section, geriatric screening, and CGA when necessary, will allow diagnosing specific impairments. Patient’s status a few months before diagnosis should be also considered because a recent degradation of performance status may lead to improvement in case of treatment response.

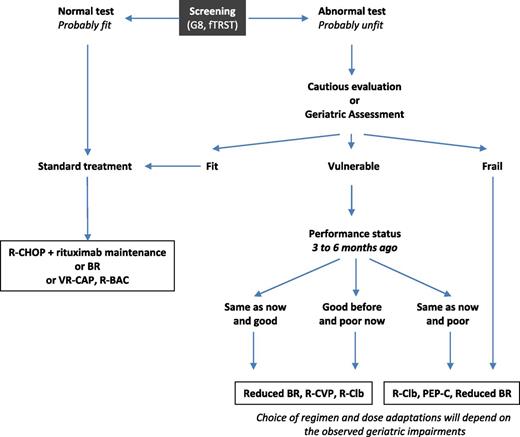

Treatment possibilities in MCL have changed a lot in the past 5 years and new treatment options are available for the management of elderly patients. Depending on fitness evaluation, 3 groups of patients should be considered and treatment objectives defined accordingly: fit patients who should be treated as younger subjects, vulnerable patients who should receive cautious (reduced) standard treatment of disease control while maintaining quality of life, and frail patients who should undergo palliative treatment to control symptoms and maintain quality of life. This is true not only for daily practice but also for clinical trials although often neglected as outlined in recent reviews.24,25

In a recent series from the Nordic Lymphoma Group,3 among 1389 patients with MCL, 67% were older than 65 years. They received a specific treatment very different from that of younger patients, including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) with rituximab (R-CHOP) or without rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) combination, bendamustine or chlorambucil mainly. Although cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) appeared inferior to other regimens, only rituximab and autologous stem cell transplantation appeared to improve survival in the multivariate analysis. The positive influence of rituximab on survival was also observed in a French population-based study.2 These data, including the variability of treatments proposed, outline the heterogeneity of patients that can be deciphered by geriatric assessment.

Consensus has been achieved on reasonable treatment options in patients unable to benefit from intensified therapy.26 Besides fit elderly patients who should benefit from either conventional immunochemotherapy (mainly R-CHOP regimen) followed by rituximab maintenance,27 bendamustine-rituximab (BR)28,29 combination or more innovative combinations such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (VR-CAP; bortezomib)30 or rituximab, bendamustine, and cytarabine (R-BAC),31 treatment options for vulnerable patients should be based on the same standard therapy but at reduced dose such as reduced BR, CVP with rituximab (R-CVP) or the combination of rituximab with chlorambucil.32,33 These same combinations can be proposed to frail patients but with more caution, together with the possibility of an oral regimen such as prednisone, etoposide, procarbazine, and cyclophosphamide (PEP-C).34 However, reliable classification criteria do not exist to identify the 3 categories of patients and the data available from these series (Table 3) do not specify the frailty status. It is therefore not possible to outline results according to the 3 categories of older patients.

First-line treatment trials in elderly patients with MCL

| . | n . | CR % . | PFS . | OS . | Grade 3-4 neutropenia % . | Febrile neutropenia % . | Fatigue % . | Severe fatigue % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP21x827 | 239 | 34 | ND | 62% (4 y) | 60 | 17 | 58 | 6 |

| RB28 | 46 | 40 | 61% (4 y) | ND | 29 | ND | 16 | ND |

| RB29 | 36 | 50 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 44 | ND |

| VR-CAP30 | 243 | 53 | 24.7 mo (median) | 64% (4 y) | 85 | 15 | 23 | 6 |

| R-BAC31 | 20 | 95 | 95% (2 y) | 95% (2 y) | 17 | 12 | 35 | 5 |

| R-chlorambucil32 | 20 | 90 | 89% (3 y) | 95% (3 y) | ND | None | ND | ND |

| R-chlorambucil33 | 14 | 36 | 15 mo (median) | 26 mo (median) | 36 | ND | ND | ND |

| RiBVD36 | 74 | 74 | 70% at 2 y | ND | 51 | 5 | 19 | ND |

| Lenalidomide-rituximab37 | 38 | 64 | 85% (2 y) | 97% (2 y) | 50 | 5 | 74 | 8 |

| Ibrutinib38 | 139 | 72 | 41% (2 y) | 68% (1 y) | 13 | ND | 22 | 4 |

| . | n . | CR % . | PFS . | OS . | Grade 3-4 neutropenia % . | Febrile neutropenia % . | Fatigue % . | Severe fatigue % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP21x827 | 239 | 34 | ND | 62% (4 y) | 60 | 17 | 58 | 6 |

| RB28 | 46 | 40 | 61% (4 y) | ND | 29 | ND | 16 | ND |

| RB29 | 36 | 50 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 44 | ND |

| VR-CAP30 | 243 | 53 | 24.7 mo (median) | 64% (4 y) | 85 | 15 | 23 | 6 |

| R-BAC31 | 20 | 95 | 95% (2 y) | 95% (2 y) | 17 | 12 | 35 | 5 |

| R-chlorambucil32 | 20 | 90 | 89% (3 y) | 95% (3 y) | ND | None | ND | ND |

| R-chlorambucil33 | 14 | 36 | 15 mo (median) | 26 mo (median) | 36 | ND | ND | ND |

| RiBVD36 | 74 | 74 | 70% at 2 y | ND | 51 | 5 | 19 | ND |

| Lenalidomide-rituximab37 | 38 | 64 | 85% (2 y) | 97% (2 y) | 50 | 5 | 74 | 8 |

| Ibrutinib38 | 139 | 72 | 41% (2 y) | 68% (1 y) | 13 | ND | 22 | 4 |

ND, not determined; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RB, rituximab bendamustine.

Practically, usual thresholds for considering each questionnaire abnormal are as follows: at least 1 grade ≥3 comorbidity on the CIRS-G (excluding the cancer being treated), ADL ≤5, IADL ≤7 across sexes, MNA ≤23.5, MMSE ≤23/30, GDS15 ≥6, and TUG >20 seconds. Further information about each questionnaire is available in the literature.35

Patients with no abnormal questionnaire should be considered as fit. Patients with 1 or more abnormal questionnaires should be considered as unfit that is either vulnerable (able to recover) or frail (unable to recover). However, it is, up to now, difficult to distinguish between vulnerable and frail patients without the help of geriatricians because no specific scoring currently exists.

Evolution of performance status from 3 to 6 months before diagnosis to baseline may help classifying vulnerable patients. Patients with either good performance status at baseline or 3 to 6 months before should receive appropriate treatment to control disease. Patients with poor performance status at both baseline and 3 to 6 months before should receive cautious treatment as frail patients. A decision algorithm is outlined in Figure 2.

Treatment decision algorithm for first-line MCL patients. R-Clb, rituximab, chlorambucil.

Treatment decision algorithm for first-line MCL patients. R-Clb, rituximab, chlorambucil.

Yet, further research should focus on the design of new schedules with an improved efficacy-to-toxicity ratio. New combinations with targeted therapies, high complete response (CR) rates, and favorable toxicity profiles, may be well suited for unfit patients. Overcosts should be considered and analyzed in comparison with standard therapy but their favorable toxicity profile may limit complications and unplanned hospitalizations so that overall costs may be limited as compared with standard therapy. Bortezomib-based combinations specifically devised for older patients, such as BR with bortezomib and dexamethasone (RiBVD),36 which showed high efficacy (76% CR/unconfirmed CR and 86% molecular CR) with a favorable toxicity profile (51% and 36% grade 3-4 neutropenia and thrombopenia and 5% febrile neutropenia, 19%, 14%, and 7% grade 3 or 4 fatigue, neuropathy, or cardiac toxicity), could be considered. Combinations of lenalidomide with rituximab37 are also good candidates because of high CR (64%) and moderately good toxicity (50% grade 3-4 neutropenia and 5% febrile neutropenia, 8% severe fatigue) rates. Ibrutinib appears even more appealing in older patients38 with a 72% CR rate and a favorable toxicity profile (13% grade 3-4 neutropenia and 4% severe fatigue).

Although these regimens have been proposed in relatively older patients, most of them had performance status 0 to 2, suggesting that unfit patients were excluded. Furthermore, analysis should also consider low-grade toxicities because they may have severe consequences in the elderly. For example, grade 2 neuropathy may increase an already existing risk of falls and its related consequences. In a series of 109 patients treated with various types of chemotherapy, Tofthagen et al analyzed factors predictive of falls and found that the number of cycles and loss of balance were independent predictors.39 With the targeted treatments referenced above,37,38 severe fatigue was infrequent with both regimens (4% and 8%) but overall fatigue was common, from 74% with lenalidomide rituximab to 22% with ibrutinib, which may lead to consideration of ibrutinib as a better choice. Consequently, further trials focused on vulnerable elderly are necessary.

Cardiac comorbidities are also of particular importance in the elderly. Overall data are limited but deserve consideration. Indeed, in patients receiving anthracycline treatment, the risk of congestive heart failure is related to other cofactors including hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and age.40-42

Conclusions

It is time to consider the elderly question in MCL; observation shows that there is room for improvement. Defining clear treatment objectives from baseline, taking into account patient’s functional status and personal views, is crucial. Geriatric assessment may help hematologists clarify the situation of each patient. But this time-consuming process should be preceded by a screening examination to limit the assessment to patients who may benefit from it. Geriatric assessment will outline patients’ vulnerabilities and thus influence treatment strategy to avoid toxicities that may worsen geriatric impairments and consequently quality of life. The next step will involve evaluating whether the intervention of geriatric defects improves the outcome of these patients as already demonstrated in the general population.43 However, evidence of the effectiveness of this resource-consuming and, thus, expensive process is missing in the oncology setting44 so that it cannot be introduced in the daily practice without previous demonstration of its effects.

MCL treatment should be based on standard therapy, either full dose or reduced, until new appealing targeted therapies have been proven valid. Yet, as outlined here, some treatment options, such as BR or even PEP-C, may be better suited for unfit patients. The lack of prospective data in unfit patients should lead investigators to develop specific research protocols with appropriate end points.

Correspondence

Pierre Soubeyran, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Bergonié, Comprehensive Cancer Center, 229 Cours de l'Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux Cedex, France; e-mail: p.soubeyran@bordeaux.unicancer.fr.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.S. is on the Board of Directors or an advisory committee for Celgene and Teva, has received research funding from Roche, has received honoraria from Spectrum Pharmaceuticals and Pierre Fabre, and has received travel grants from Celgene, Teva, and Hospira. R.G. declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.