Abstract

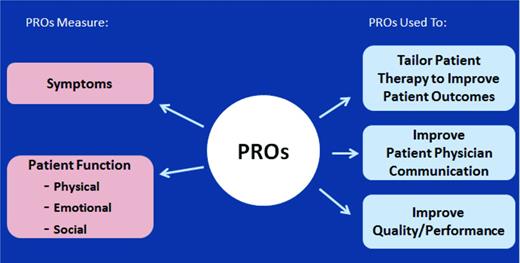

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement plays an increasingly important role in health care and understanding health outcomes. PROs are any report of a patient's health status that comes directly from the patient, and can measure patient symptoms, patient function, and quality-of-life. PROs have been used successfully to assess impairment in a clinical setting. Use of PROs to systematically quantify the patient experience provides valuable data to assist with clinical care; however, initiating use of PROs in clinical practice can be daunting. Here we provide suggestions for implementation of PROs and examples of opportunities to use PROs to tailor individual patient therapy to improve patient outcomes, patient–physician communication, and the quality of care for hematology/oncology patients.

Learning Objectives

To understand the utility of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice

To develop strategies for implementation of PROs into clinical practice

Patient-reported outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement plays an increasingly important role in health care and understanding health outcomes. PROs are any report of a patient's health status that comes directly from the patient. PROs inform clinicians and researchers about issues associated with health status that are most important to patients and their families, and generate data to facilitate improved care of the patient. Given these benefits, governing agencies have recommended assessing PROs in health care as evident by the FDA's PRO guidance publications1 for the drug industry and the NIH's Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) initiative.2

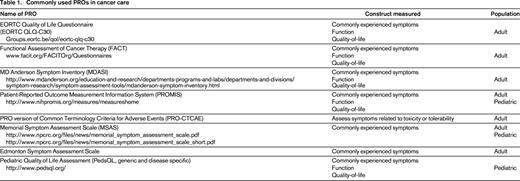

PRO measures provide composite scores from a series of questions around a central concept to quantify the level of distress or impairment caused by a patient's symptoms, disease, or treatment. A variety of PROs have been developed and validated to assess symptoms (such as nausea and vomiting, insomnia, constipation, and pain), patient physical, social, and emotional function, and more complex constructs such as impact of health on peer relationships. There are generic and disease-specific PROs that can be used to measure these outcomes, as well as available measures for use in pediatric and adult patients. See Table 1 for commonly used PROs.

PROs systematically quantify patient experiences

Adults and children with cancer commonly experience symptoms that lead to impaired physical function, emotional function, and social function resulting in decreased health status.3-7 Patient symptoms often go undetected during typical clinic interviews, and clinicians may underestimate the impact of symptoms from interview alone.8-10 The impact of cancer and cancer treatment on patient health status can be systematically quantified using PRO measures in children and adults.5,11,12 Use of PROs in these populations has identified symptoms and impairments in patient function. Most patients receiving treatment experience decreased health status13,14 ; however, cancer patients with better symptom management and better PROs live longer with less distress.15-17 PROs generate data that can facilitate better care regardless of diagnosis or prognosis for cancer patients.

PRO use in clinical practice is feasible and beneficial

PRO measures are recognized tools that can be used to assess impairment in a clinical setting.9,18-21 Multiple studies confirm that clinical integration of PROs does not increase the duration of clinic visits, that provider and patient satisfaction is high, and that all parties feel their use improves communication.12,19,20,22-24

The successful use of PROs in outpatient orthopedic surgery clinics highlights the feasibility of use in busy outpatient settings and the benefit in clinical decision making. Orthopedic clinics have integrated PRO collection into clinical practice to monitor patient pain, mobility, and function. These data are used to monitor improvement or deterioration in function related to the condition, assess response to nonsurgical interventions, and assist with decision making regarding elective surgical interventions for knee, hip, or back problems.21,25

PRO use improves physician patient communication

Several randomized trials have examined the impact of clinical use of PROs on patient–physician communication in adult oncology patients. In these studies, providers were randomized to receive PRO data compared with control groups who did not receive PRO data prior to clinic visits. Salient issues related to PROs, such as psychosocial issues and symptoms were more likely to be discussed for visits where the clinical team received the summary.12,19,20 Some patients experienced better functioning as a result of the intervention.12 Similar work in children with advanced cancer and pediatric cancer survivors has demonstrated that providing PRO data to clinicians increased discussion of psychosocial issues and improved the patient's health status in certain subpopulations (see Example 1).23,24,26

Electronic data collection and use within electronic medical records (EMRs)

Use of EMRs in the United States is required for public and private healthcare providers to maintain Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement. Integration of PROs into EMR is a vital step toward improving accessibility and user-friendliness of PROs in clinical and research settings.27 To illustrate the benefit of PRO integration into EMRs, we will highlight one large EMR, Epic. The next version of Epic will contain functionality to collect PROs and integrate PRO data into the EMRs. Patients whose healthcare providers use Epic can sign up for MyChart, an electronic portal that allows patients to view laboratory and imaging reports, schedule appointments, and communicate non-urgent issues with their providers. Certain existing PROs have been integrated with the MyChart system, with the ability to create additional disease- or clinic-specific PROs. Providers can identify which PROs they would like patients to complete and send them secure email notifications via the MyChart portal. Once complete, the PROs integrate within the Epic EMR and can be viewed alongside other clinical data by the provider. Providers have the ability to visually examine the impact of interventions on PRO scores to understand the impact of care decisions from the patient's perspective (Figure 1).28

Conceptual framework for PRO integration in clinical care.

Conceptual framework for PRO integration in clinical care.

Use of PROs in clinical practice is not limited to practitioners who use EPIC or whose systems have already integrated PROs into their EMRs. A practical work-around for lack of PRO integration into the EMRs is collection of electronic PROs using RedCap. RedCap is an electronic data management system that currently has functionality to collect a variety of PROs, including a wide variety of generic and disease-specific instruments for pediatric and adult patients. The full list of available instruments can be found at http://project-redcap.org. Custom PROs can be built into RedCap to meet the specific needs of the users.

The majority of work integrating electronic PRO collection into the clinical setting has been done in adult patient care settings. A pilot study in pediatric sickle cell, oncology, and bone marrow transplant patients confirmed the feasibility of obtaining electronic PROs in the pediatric clinic setting.29 Electronic PROs were captured on tablets in the clinic waiting room and the results of the PROs were provided to the clinicians during the visit. Cincinnati Children's Hospital has adopted a tablet and kiosk-based system to collect PROs in their outpatient clinics under an initiative to improve quality of care, demonstrating feasibility within a large pediatric healthcare system and diverse patient populations.28

PROs Can be used to tailor supportive care for individuals

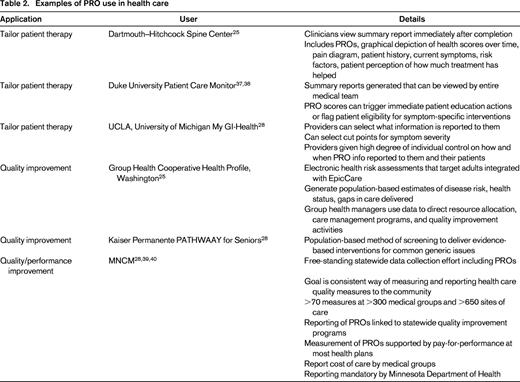

The ultimate goal of health care is to restore or preserve functioning and well-being related to health.30 Achieving this goal in hematology/oncology care is challenging because many distressing symptoms are subjective in nature. Use of PROs to systematically quantify the patient experience provides valuable data to assist with clinical decision making.31,32 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network acknowledges that symptoms, such as fatigue and pain are “a subjective experience that should be systematically assessed using patient self-reports” (www.nccn.org). However, operationalization of this process can be cumbersome and prohibitive to clinical practices. Table 2 highlights healthcare systems that have successfully integrated PROs into practice by utilizing the power of electronic PROs integrated into EHR to tailor care for individuals. Here we provide several additional examples of clinical use of PROs.

Example 1.

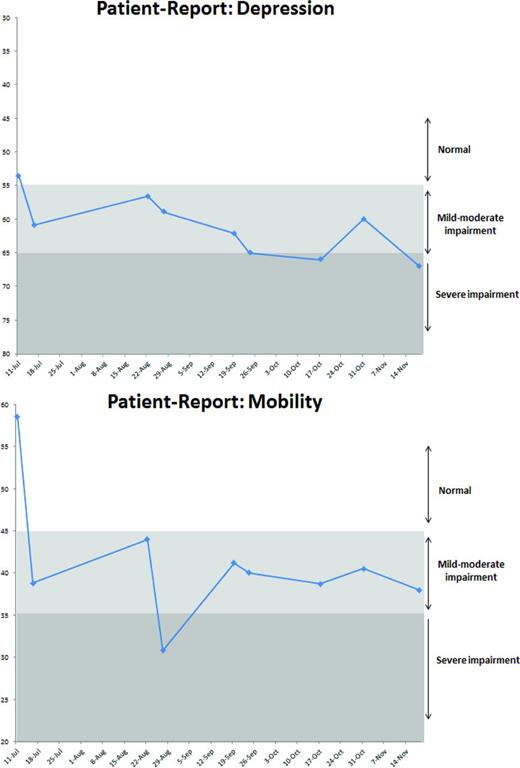

Patients seen in clinic for routine care complete PROs measuring commonly experienced symptoms (eg, pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and impaired physical mobility). PRO scores and trends over time are available for review at interdisciplinary patient staffing meetings. Providers can review PRO scores and discuss interventions. For example, the case of a patient receiving therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma is reviewed monthly at a staffing meeting that includes the program nurse coordinator, advanced practice provider, physician, social worker, and psychologist. Review of her case reveals that she is continuing along her prescribed treatment course without incident and she seemed well at her last visit. Review of her PRO scores demonstrate worsening depressive symptoms as she moves farther into her chemotherapy course. Additionally, her physical function is worsening as she progresses through treatment (Figure 2). This information triggers an additional clinic visit to thoroughly assess these symptoms and to create action plans including engagement of the psychology and physical therapy teams in her care and assessment of her ability to care for herself at home.

Hypothetical PRO data output for review at patient staffing.

Hypothetical PRO data output for review at patient staffing.

Example 2.

Patients followed for management of sickle cell disease are seen annually in a comprehensive clinic (interdisciplinary clinic involving the nurse coordinator, physician, advanced practice provider, social work, psychology, physical therapy, and genetic counselor) and every 2-3 months for management of hydroxyurea therapy. Patients complete a full battery of PROs at the annual comprehensive clinic visit (includes measurement of a wide variety of symptoms, physical, social, emotional function, and global quality-of-life) and a smaller battery of disease-specific PROs at each hydroxyurea clinic (pain, fatigue). The comprehensive battery provides a more complete and longitudinal view of the patient's health status and impact of disease over time, whereas the disease-specific symptom-directed PROs collected at hydroxyurea visits provide targeted information regarding patient symptoms over time. For example, a teenage boy with Hg SS disease is seen in comprehensive sickle cell clinic for his first visit after moving from another state. PROs collected at this visit indicate that he has significant difficulty with pain and fatigue causing him to miss significant time at school. This is in turn impacting his social relationships and his mood. The clinical team initiates hydroxyurea therapy and the team psychologist begins to work with the patient. He is followed every 2-3 months over the upcoming year. PROs quantifying pain and fatigue begin to improve after several months of hydroxyurea treatment. The comprehensive battery at his next annual visit indicate continued difficulty but improved pain and global quality-of-life, improving school attendance, and improving peer relationships. He continues to work with the team psychologist for management of depressive symptoms and strategies to deal with his pain.

Quality and performance improvement

Quality improvement examines processes in order to improve them. It consists of systematic and continuous actions that lead to measurable improvement in health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups. The Institute of Medicine defines quality in health care as a direct correlation between the level of improved health services and the desired health outcomes of individuals and populations.36 Using PROs to understand these desired health outcomes provides valuable measures to gauge quality of certain aspects of care. Table 2 highlights several applications of PRO data in quality improvement.

Performance improvement addresses human performance within organizations at the individual, process, and organizational levels. The use of PROs as performance measures in hematology/oncology has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum and the International Society for Quality of Life Research and recommendations for the process have been described.35 This application of PROs is currently in its infancy, an example of PRO use for this purpose is detailed in table 2.

Challenges to PRO implementation and lessons learned

Implementation of PROs presents challenges to healthcare providers and systems, however, solutions exist to overcome barriers and successfully use PROs in clinical practice. As mentioned previously, PRO use is not limited to healthcare providers whose EMR has integrated PROs. Electronic data capture of PROs is possible using several different platforms and can be worked into clinical workflows accordingly.

The manner by which PROs are collected (eg, EMR before clinic visit versus PRO collection at clinic visit via RedCap) will influence the setting in which data is reviewed by the clinical team as well as how PRO data is reviewed with the patient. When PRO results are available to providers prior to a patient visit, it is ideal to review the data with the patient and use the information for shared medical decision making in real time. When PROs are available for review after the patient encounter, decision making around an issue is likely to happen over the telephone, in person at an additional clinic visit specifically to address the concern, or at the next scheduled visit depending on the clinical scenario. The decision to have real-time PRO data available for a scheduled clinic visit or to review these data post-visit depends largely on the ability of the health care system to support the collection and scoring of the data in a timely manner and for the health care team to be educated in interpreting the results.

An additional barrier to successful integration of PROs to support clinical practice is determining which PROs to collect from patients and at what time intervals. The International Society for Quality of Life Research has published a user's guide to help aid clinicians who want to implement PRO measurement into their practices.33 Consensus recommendations for PRO inclusion in adult cancer clinical trials recommend measurement of health-related quality-of-life and commonly experienced symptoms (anorexia, anxiety, constipation, depression, diarrhea, dyspnea, fatigue, insomnia, nausea, pain, neuropathy, and vomiting).34,35 It is reasonable to choose from this battery of PROs and tailor to the needs of the individual patient population, considering which elements are most applicable in any given clinical setting. To limit patient burden and increase completion rates, consider soliciting a full battery of measures initially and at longer intervals as demonstrated in Example 2 (eg, annual completion of global HRQL measure, pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, social function, and sexual function), with more frequent assessment of most salient measures of symptoms for which clinicians are able to intervene or may inform management decisions (eg, monthly or quarterly assessment of pain, fatigue, and nausea/vomiting).

Feasibility and process issues in individual clinics are best addressed by implementation of PROs first in a limited patient population as well as with a limited number of healthcare providers. This allows for rapid process evaluation and improvement cycles from both the patient and provider perspective prior to widespread implementation. Lastly, support from key stakeholder groups including administrators, healthcare providers, ancillary staff, IT personnel, and patient advocates is key to successful implementation of PROs in clinical practice.

Summary

Integration of PROs into clinical care is a vital step toward individualizing patient care and making care truly patient-centered. Keys to successful integration of PROs into clinical care include: (1) buy-in of administrative leaders, clinicians, and patients; (2) customization of PRO measures to meet goals and needs of each clinical practice; and (3) electronic capture of PRO data.

Correspondence

Julie Panepinto, Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Medical College of Wisconsin/Children's Research Institute of the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226; Phone: 414-456-4170; Fax: 414-955-6543; e-mail: jpanepin@mcw.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: S.D. declares no competing financial interests; J.P. has received research funding from HRSA and NIH and has consulted for NKT Therapeutics.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.