Abstract

Children with advanced cancer, including those with hematologic malignancies, can benefit from interdisciplinary palliative care services. Palliative care includes management of distressing symptoms, attention to psychosocial and spiritual needs, and assistance with navigating complex medical decisions with the ultimate goal of maximizing the quality-of-life of the child and family. Palliative care is distinct from hospice care and can assist with the care of patients throughout the cancer continuum, irrespective of prognosis. While key healthcare organizations, including the Institute of Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Society of Clinical Oncology among many others endorse palliative care for children with advanced illness, barriers to integration of palliative care into cancer care still exist. Providing assistance with advance care planning, guiding patients and families through prognostic uncertainty, and managing transitions of care are also included in goals of palliative care involvement. For patients with advanced malignancy, legislation, included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act allows patients and families more options as they make the difficult transition from disease directed therapy to care focused on comfort and quality-of-life.

Learning Objectives

To understand the barriers and benefits of integration of palliative care into the care of children with hematologic malignancies

To describe the goals of palliative care involvement in children with hematologic malignancies

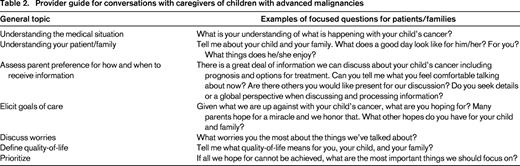

The past decade has seen a rapid transformation in the field of pediatric palliative care. Broad use of palliative care for children with serious illness has been endorsed by key organizations including the Institute of Medicine, The American Academy of Pediatrics and The American Society of Clinical Oncology. Palliative care for children is now understood as distinct from hospice and end of life care. Palliative care combines medical, psychosocial, and spiritual care to enable children with serious, potentially life threatening illnesses to maximize their quality-of-life and to have medical decisions made based on the goals and values of the child and family (Table 1).

WHO definition of palliative care for children (http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/)

Children with advanced cancer can benefit from the integration of palliative care into cancer care. The American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy statement in 2013 entitled, “Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice Care: Commitments, Guidelines, and Recommendations,” to promote the welfare of infants and children living with life-threatening or inevitable life-shortening conditions and their families through the provision of effective curative, life-prolonging, and quality-of-life enhancing care.1 This report highlighted the importance of integration of palliative care into the continuum of care, the need for hospitals that routinely care for children who die to have interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care teams, and the importance of providing bereavement services to the siblings of pediatric patients who are gravely ill or who die, as well as to other family members and to healthcare staff. The American Society of Clinical Oncology voiced support of the integration of palliative care into routine comprehensive cancer care in the United States by 20202 and followed with a provisional clinical opinion that combined standard oncology care and palliative care should be considered early in the course of illness for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden.3

Despite these recommendations, integration of palliative care into the care of children with advanced cancer, including those with hematologic malignancies is not routine. Many barriers have been described including the prognostic uncertainty of many pediatric cancers, lack of training for providers, lack of interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care teams, and lack of evidence for the benefits of palliative care interventions.4-6 Some pediatric oncologists are reluctant to involve palliative care teams early due to concerns that it may change their relationship with their patients and families. Others had conflicting philosophies about whether palliative care is consistent with the goals of curative treatments.6

Pediatric palliative care for children with advanced cancer

Despite advances in cancer directed and supportive therapies, >2 000 of the 12 000 children diagnosed annually with cancer will not survive.7 Multiple studies have indicated that children with advanced cancer experience high degrees of symptom burden and distress both from physical and emotional causes.8,9 Although availability of interdisciplinary palliative care teams for children with cancer is growing with 58% of Children's Oncology Group institutions report having a pediatric palliative care team, there remains a lack of consistency in the staffing of these programs.10,11 At the same time, evidence to support the impact of palliative care services is growing. A number of studies have documented benefits of palliative care consultation for children and families, including: improved family satisfaction with care, management of distressing symptoms, communication with healthcare providers, and earlier recognition of prognosis and care coordination.12-15 A recent study compared demographic and clinical features of 24 342 children who died ≥5 days after admission in a sample of children's hospitals, comparing patients who did and who did not receive a palliative care consultation. Only ∼4% of children were identified as having received palliative care. Children who received palliative care in this study had fewer median days in the hospital (17 vs 21), received fewer invasive interventions, and fewer died in the ICU (60% vs 80%).16 Studies specific to children with advanced cancer have indicated palliative care intervention can have numerous benefits including improved management of distressing symptoms, better communication, earlier recognition of prognosis, and reduced hospitalizations.14,17,18 Wolfe et al showed that an increased focus on palliative care for children treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Children's Hospital Boston resulted in improvements in advanced care planning. In addition, parents reported better preparedness for their child's end of life course and decreased suffering in their children.14 Parents of children with cancer associated quality end-of-life care with: (1) physicians giving clear information about what to expect in the end-of-life period, (2) communicating with care and sensitivity, (3) communicating directly with the child when appropriate, and (4) preparing the parent for circumstances surrounding the child's death.19

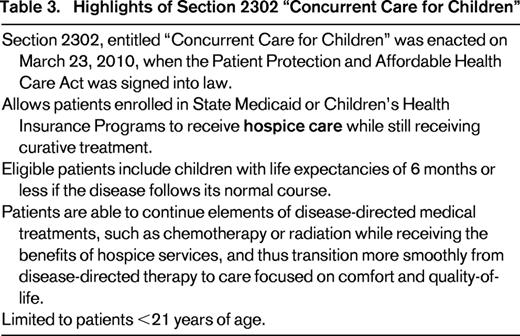

Clinical standards for quality of palliative care have been developed.20 Although parents and clinicians value most of the core elements, very few are reported as routinely accessible with the least likely accessible being a direct admission policy to the hospital, sibling support, and parent preparation for medical aspects surrounding death.21 This same study of bereaved parents and clinicians reiterated others that indicate that although parents seek all available cancer therapies, even with minimal hope for disease benefit at the time of their child's cancer progression, in retrospect they can have decisional regret and recall cancer directed therapy as being associated with increased suffering at the end of life. This highlights the importance of having compassionate, honest conversations with caregivers related to goals of care (Table 2).21-24

Goals of palliative care referral for children with hematologic malignancies

The overarching goal of palliative care is to craft an individualized care plan that addresses the unique needs of each patient as it pertains to mitigating suffering and maximizing a patient's quality-of-life. Specifically, the following domains are assessed and reassessed throughout the patient's palliative care journey: pain and other symptoms, psychosocial stressors, spiritual stressors, advanced care planning needs, and care coordination needs. Areas of strengths are identified and highlighted to the patient and family; similarly, areas of stress that threaten the comfort of the patient are also identified and a care plan is designed to aid these needs.

Symptom management

Pediatric oncology patients facing end of life are burdened with a significant number of symptoms including pain, nausea, fatigue, and anorexia. Studies demonstrate that these symptoms are both under identified and under treated during the last week of life.8,9,25 A prospective study describing patient reported outcomes in children with advanced cancer found that from their own perspective, children experience high physical and psychological symptom distress from common, treatable symptoms including pain, fatigue, drowsiness, and irritability. In this study, physical symptom prevalence and distress appears to worsen in the last 12 weeks of life.8

Symptoms are a primary focus of palliative care as experts seek a functional plan that is compatible with the home setting, facile with the goals of the patient, and are easily able to be escalated. Additionally, palliative care teams are either equipped or partner with home-based nursing programs that allow for home visits and remote support to constantly reassess a patient's pain needs with the goal of optimizing her comfort and health in the outpatient setting. These goals remain regardless if patient has chosen to elect his hospice benefit or if he is a palliative patient pursuing life prolonging or curative therapies.

When considering the role of palliative care in the oncology population, it is important to note that oncologists often possess a robust knowledge of symptom management. Additionally, the long-standing relationships that most oncologists possess with their patients allow for the necessary trust and communication that optimizes symptom management. As a result, palliative care teams may be perceived as redundant by oncologists.26

However, there is research to show the necessity for palliative care collaboration in managing oncology patients. Symptom burden is heavy as referenced above. Additionally, both Wolfe and Ulrich both showed that parents retrospectively recollect incomplete identification and management of end of life symptoms in children.9,25 Oncologists' closeness to their patients and the situation may make them less able to perceive suffering. Palliative care can act as a third-party member to survey for persistent symptoms and intercede accordingly.27 This could be particularly important in the inpatient setting, where the number of symptoms in pediatric oncology patients has been shown to be higher than outpatient oncology patients.

When one focuses upon patients with hematologic malignancies, research suggests that adult patients have a higher burden of symptoms with an average of 8 symptoms at any point in time.28 Tecchio showed a heavy burden of symptoms (fatigue, dry mouth, worry, insomnia, drowsiness, and feeling sad) especially if hematologic malignancy patients are receiving chemotherapy or needed to be hospitalized.29 Pritchard shows a similar burden in pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies who have significant dyspnea, elevated heart rates and change in behaviors that were concerning to parents.30 Despite this, patients with hematologic malignancies are less likely to receive a palliative care consult than those with solid tumors.28 While overall palliative care referrals are less frequent in hematologic malignancy patients, oncologists may identify palliative care's value as symptom experts in patients with refractive symptoms.

Psychosocial and spiritual support

Palliative care teams are interdisciplinary in order to address the realities that a person and those closest to them can experience suffering through any aspect of the disease or disease process. Thus, palliative care teams often possess a social worker, chaplain, counselor art therapist, and/or child life therapist. However, research again suggests that pediatric oncology programs do not necessarily see the addition of these services as a reason to refer to palliative care since these disciplines are often embedded within their own program.5 However, palliative care chaplains, social workers, and music therapists now have certification programs specific to palliative care, which sets them apart from colleagues within the oncology programs and represent expert resources for patients, families, and the oncology staff. Recently, a conceptual model for approaching pediatric palliative care and psychosocial support in oncology settings has been developed. Priorities identified included holding to hope, honest communication, relief of symptoms, care access, social support to include primary caregiver support, sibling care, bereavement care, and overall care quality.31

Such skills are of great importance when navigating the complex journey of facing a life threatening condition. One robust example of the need for palliative care expertise is when discussing the construct of hope with patients and families. Pediatric palliative care research has focused heavily upon the presence of hope in end of life decision-making and the impact that true prognostication has upon a patient or parent's level of hope. Through several studies, it has been revealed that parents of children with terminal cancer have increased hope scores when true prognostication has been transmitted by a physician.32 Additionally, true prognostication, that raises parental hope scores, has also been associated with the increased prevalence of “Do Not Resuscitate” orders.33 Oncologists may not be able to fully prognosticate out of fear they may be harming their patients. Epstein et al highlights the risks of this collusive relationship as patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia relay a perceived difficulty communicating with their healthcare team.34 Palliative care specialists have extensive training in assisting in the reframing of hope and again, may act as a “treatment broker”27 against the mutual pretense to allow for true prognostication, which can assist both the oncology team and the patient.

Such brokering can help lower the patients' and caregivers stressors and improve their quality-of-life. One study showed that pediatric patients, especially adolescents, denote sadness and isolation as a result of difficulty discussing their pending death with their parents.35 Epstein highlighted that increased psychosocial stressors associated with acute leukemia are associated with decreased patient spiritual well-being.34 The expertise of palliative care psychosocial team members in facilitating end of life discussions can be an invaluable resource to oncology psychosocial teams working with palliative care and end of life patients.

Advance care planning

Patients with hematologic malignancies are more likely to die within the hospital than in the home.28,36 Although this is a quality metric of end of life care, it is tracked as an advance care planning proxy as many adults have indicated they would prefer to die at home versus the hospital when given the choice and chance.37 Similarly parents of pediatric oncology patients also identify home as the preferred location for their child's death.38,39 Thus, there is again a vibrant role for palliative care teams, who have had extensive training in advance care planning, to collaborate with oncology programs to ensure best outcomes for patients with hematologic malignancies.

Although advance care planning is technically for competent patients >18 years of age, there is a growing body of work to utilize “family advance care planning” in adolescent oncology patients facing life-threatening conditions such as acute myelogenous leukemia.40 Although adolescent patients cannot typically have true legal consent, family advance care planning provides education and validated discussion tools, such as “Voicing My Choices”41 so that healthcare providers and family can best support the patient's choices. Adolescents and young adults living with a life threatening illness, including advanced cancer indicate they want to be able to choose and record the kind of medical treatment they want and do not want, how they would liked to be cared for, information for their family and friends to know, and how they would like to be remembered.42 With palliative care's guidance, an adolescent patient can find his voice, engage in meaningful conversations with both family and healthcare providers, and ensure that the medical care plan accurately reflects his goals of care. In turn, this can assist parents in avoiding intensive therapies that studies show they regret after their child dies.43

Navigating prognostic uncertainty

Patients, families, and care teams face a great deal of prognostic uncertainty in caring for children with hematologic malignancies. Although the overall prognosis of children diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma remains relatively good, there are those at higher risk of death including children with CNS involvement, relapse or other high-risk features.44 In addition, newer therapies including the use of chimeric antigen receptor T cells have the potential to put even those with the highest risk disease into remission.45 Given the high degree of symptom burden in children with advanced hematologic malignancies and the uncertainty of prognosis, the integration of palliative care alongside cancer directed therapy is necessary. In Wolfe's prospective study of symptoms in children with advanced cancer, >0% were alive at the 9 month follow-up. In this cohort, receiving moderate or intense cancer therapy resulted in significantly worse scores across all domains with lowering of symptom distress as disease improves or treatment intensity lessens.8 Given that outcomes of an individual child are not easily predicted, it is important to emphasize the role of palliative care in conjunction with cancer directed treatments to help decrease symptom burden from both disease and therapies.

Transitions of care

One of the barriers to full integration of palliative care into the curative treatment has been the stigma that engaging in palliative care services means giving up on the potential for life extending treatments. Although this has, in the past, been accurate for those patients who engaged in hospice services, receipt of palliative care services have never entailed foregoing any other form of treatments. Parents of children engaged with pediatric palliative care programs may choose to shift utilization to other healthcare settings beyond hospital care.46 In addition, parents and clinicians prefer home as the location for end of life care and death for children with cancer. In those who did not choose home as a location for death, hospital-based palliative care is the preferred alternative.39 Pediatric patients differ from adults who enroll in hospice in that the are less likely to have Do Not Resuscitate orders at hospice admission, have longer hospice length of stays and are more likely to die at home if they stayed in hospice.47 This highlights the nature of transitions of children from disease directed care to hospice care. Children engage in hospice services while continuing to pursue some disease directed treatments. Thus, the need to ensure continued care coordination between hospital, outpatient settings, and home is paramount.

Ensuring that a patient attains their desired goal to be at home, either as often as possible, or to die at home, requires well-organized care coordination. Additionally, for maximal comfort, both in terms of physical and non-physical stressors, a hematologic malignancy patient needs access to a home-based palliative care and/or hospice program. As discussed above, these patients have significant symptom burden and psychosocial stresses that can negatively impact their quality-of-life at home. Virtually all pediatric home-based hospice and palliative care programs work collaboratively with the primary oncologist to ensure a smooth transition to home and constant communication to maximize care.

Concurrent care for children

Given prognostic uncertainty inherent in caring for children with advanced cancers; the desire of parents to continue to pursue disease directed therapies; the preference among parents for care at home; and the need to more aggressively treat symptoms across care locations; the integration of home hospice services into the care of children with poor prognosis seems ideal.

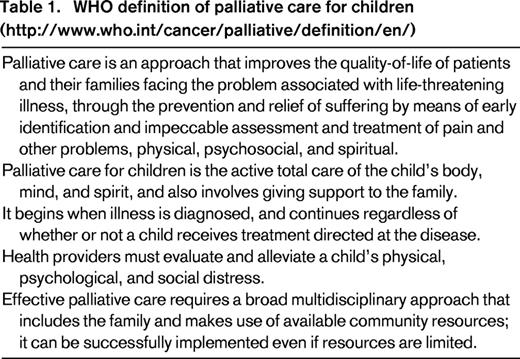

However, historically the hospice benefit required that patients must choose between continuing disease-directed treatments and receiving hospice services. Fortunately, the necessity in choosing hospice care or disease-directed care has changed for patients under the age of 21 with the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act (PPACA). This act includes a provision, entitled “Concurrent Care for Children (CCC),” which requires that programs for children in state Medicaid or Children's Health Insurance Programs (CHIP) allow children under the age of 21 to receive hospice care while still receiving potentially curative treatments.48 This program allows children who meet hospice criteria to continue potentially curative, life-extending treatments including chemotherapy, radiation, nursing support, and home technology (Table 3). There are important limitations to this provision including being limited to children receiving Medicaid or CHIP and requiring a prognosis of <6 months of life should the disease or condition follow its normal course. Despite these limitations, CCC has the potential to allow children receiving cancer therapy to also receive hospice services and thus care at home as their condition progresses. Given that many children receive cancer directed therapies in the last days, weeks, and months of life, this provision is particularly relevant to caring for children with malignancies.

Conclusion

Great strides have been made in recognizing the need to integrate palliative care into the overall care of all children with advanced cancer including those with hematologic malignancies. Benefits to patients, families, and care providers have been demonstrated and recognized by leading organizations devoted to caring for patients with cancer. Barriers to the delivery of palliative care services include provider bias, limited resources, and deficiencies in healthcare delivery systems. It is incumbent upon those caring for children with cancer to recognize the need for attention to management of symptoms, spiritual and emotional distress, and honest empathetic communication with patients and families throughout the continuum of cancer care. Involvement of a specialty palliative care team working in conjunction with the primary oncology team should be considered as part of the care plan of children with advanced cancers.

Correspondence

Tammy I. Kang, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, PACT-11th NW 90 Main, 34th and Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; Phone: 267-426-5051; Fax: 215-590-0161; e-mail: kang@email.chop.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.